مرکز علوم گیاهی هازلهیر اثر گروه طراحی و ساخت 180 دیگریز و استودیوی کُلاب، ترجمهی لادن مصطفیزاده

Hazel Hare Center for Plant Science / 180 Degrees Design + Build + colab studio

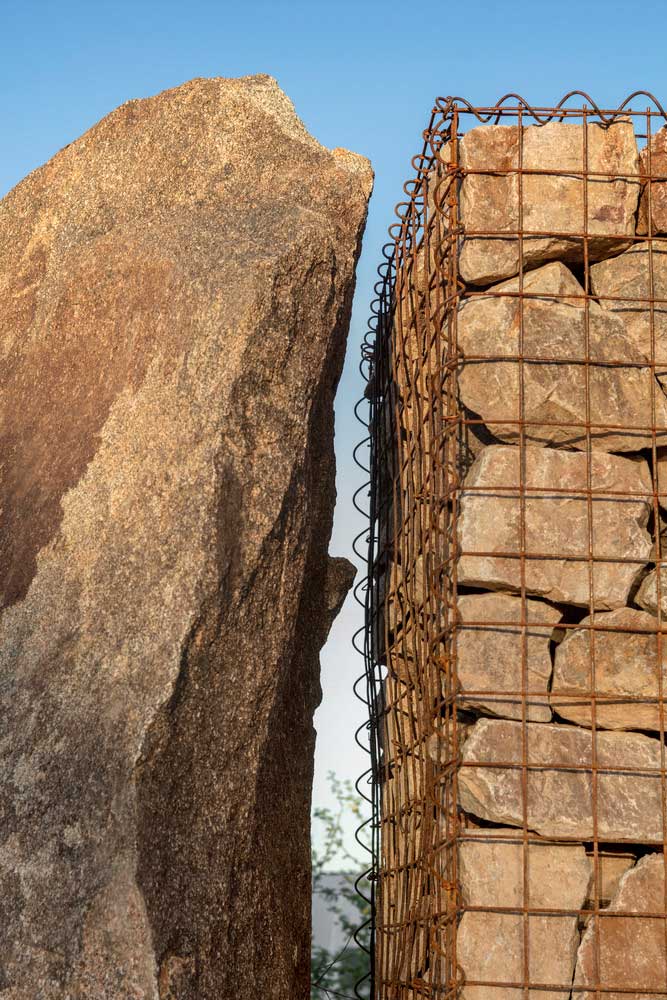

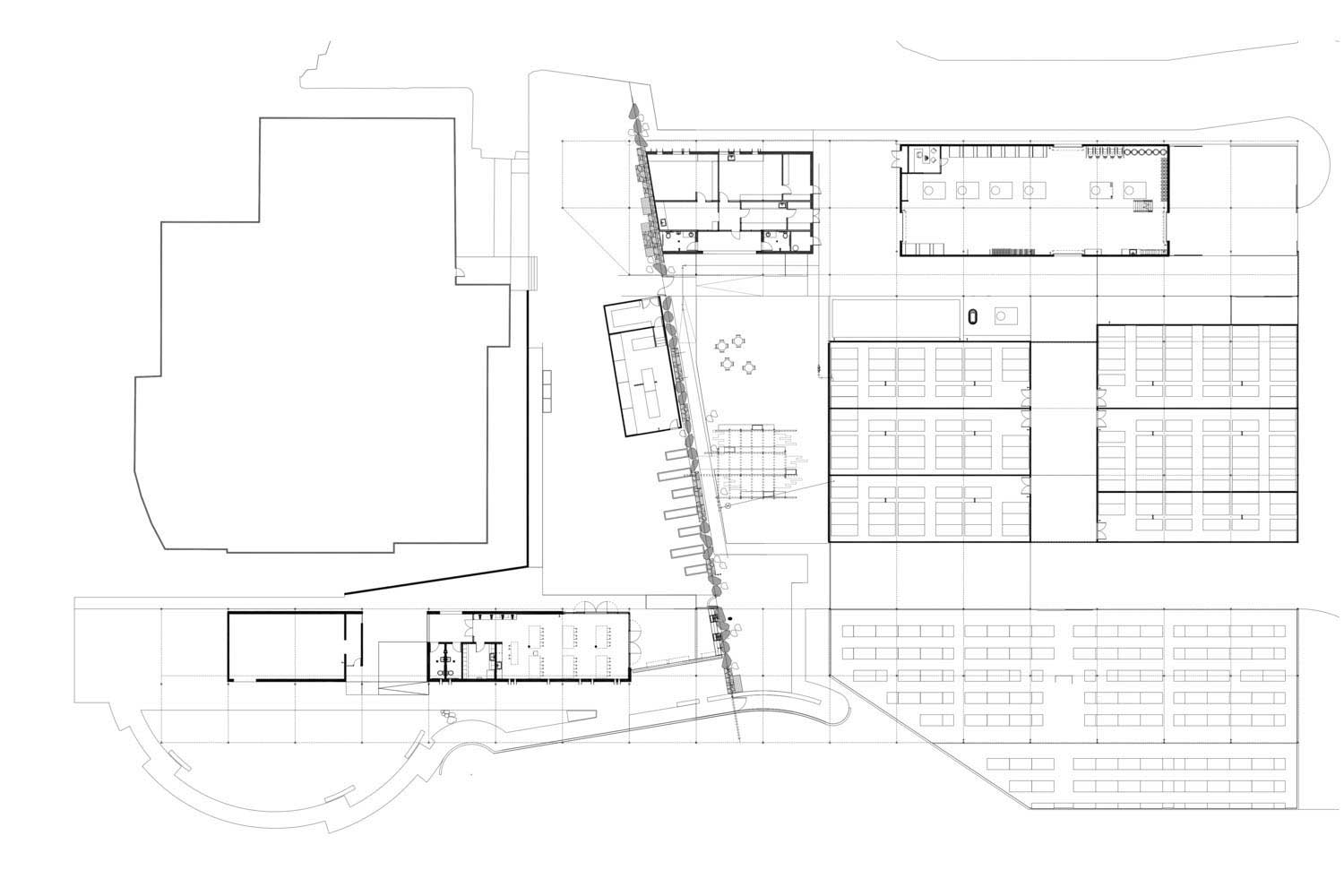

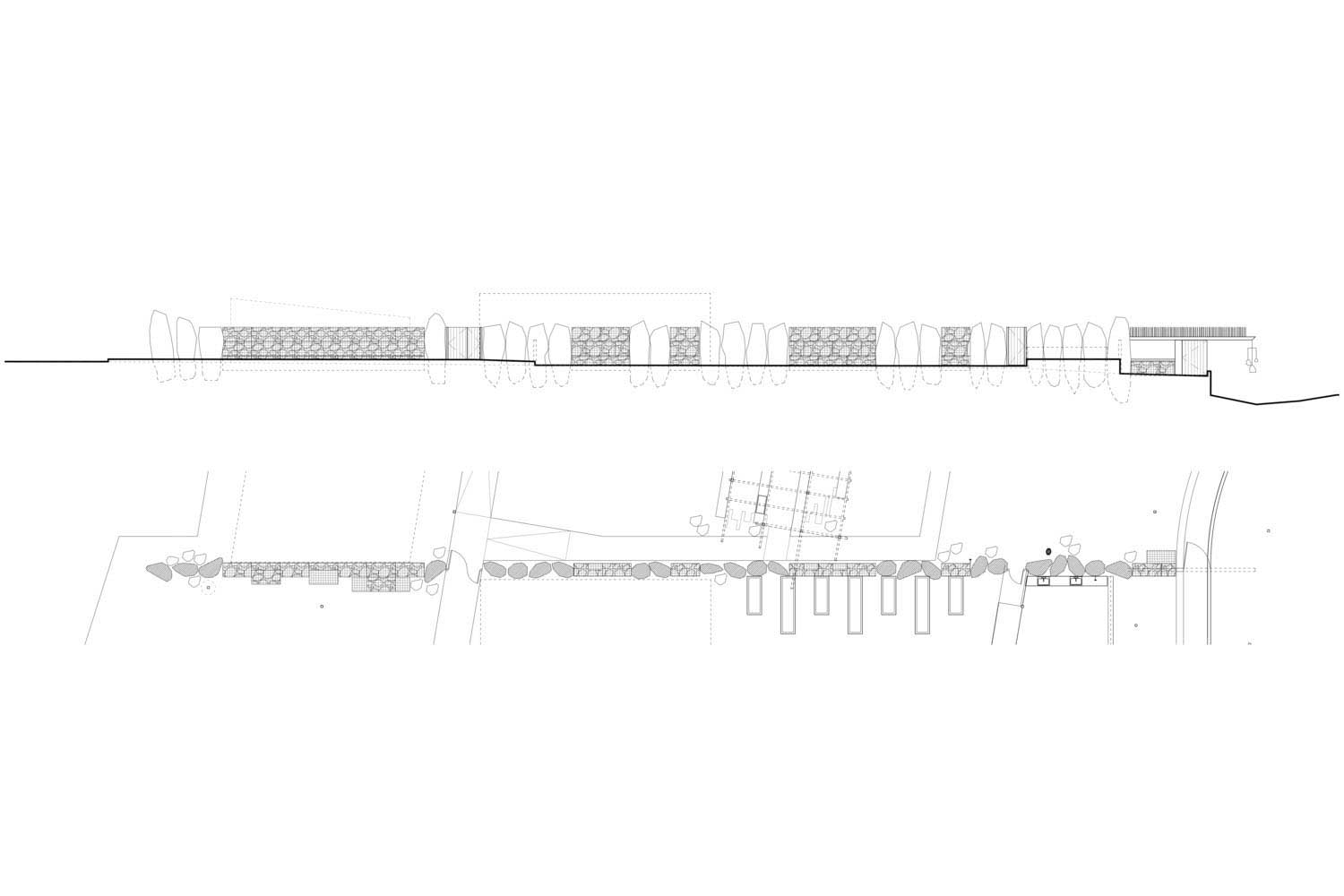

مرکز علوم گیاهی هازلهیر (Hazel Hare) با مساحت 9112 فوت مربع در سال 2018 توسط گروه طراحی و ساخت 180 دیگریز (180 Degrees Design + Build) و استودیوی کُلاب (Colab Studio) در آمریکا ساخته شده است. این مرکز که شامل گلخانه و بخشهای آموزشی میباشد، در باغ گیاهشناسی دیسرت (Desert) در پوئینکس (Phoenix) قرار دارد. در باغ گیاهشناسی دیسرت از یک مجموعه غیر معمول از سازهها (ترکیبی از چوب، بتن، استیل، سنگ و بلوک سیمانی) برای گرد هم آوردن افراد استفاده شده است که این جدا کنندههای کاربردی، فضاهای باز را از نظر فیزیکی جدا ولی از نظر بصری به هم متصل میکنند. این باغ به فضایی برای جدا کردن فضای جلوی از پشت در مرکز باغبانی نیاز داشت که امکان دسترسی و درک اهداف و نوآوریهای ساختمانها را به عموم مردم میداد. برای این تقسیم فضایی از یک دیوار سبز ساخته شده از سنگ، استفاده شد که علاوه بر کاربردی بودن، فرصت درگیر شدن استفادهکنندگان با این دیوار را نیز فراهم میکرد. هر تخته سنگ مورد استفاده در این دیوار با توجه به طول و ویژگی خاص خود انتخاب شد و یک سوم هر تخته سنگ باید در زیر زمین قرار داده شود تا بتواند وزن خود را تحمل کند. بیش از 436 تن سنگ از یک معدنی در کینگمان (Kingman) خریداری شد و سه هفته زمان برد تا این 24 تخته سنگ در جای خود قرار گیرند. کارکنان باغ و خدمه ساخت و ساز شروع به نامگذاری تختهسنگها کردند و این عمل باعث ایجاد ارتباط قوی آنها با باغ شد و برای اشاره به سنگها اغلب از این نامها استفاده میکنند. این پروژه با نوسانات مالی رو به رو بود و به این دلیل، بارها تغییر شکل داد.

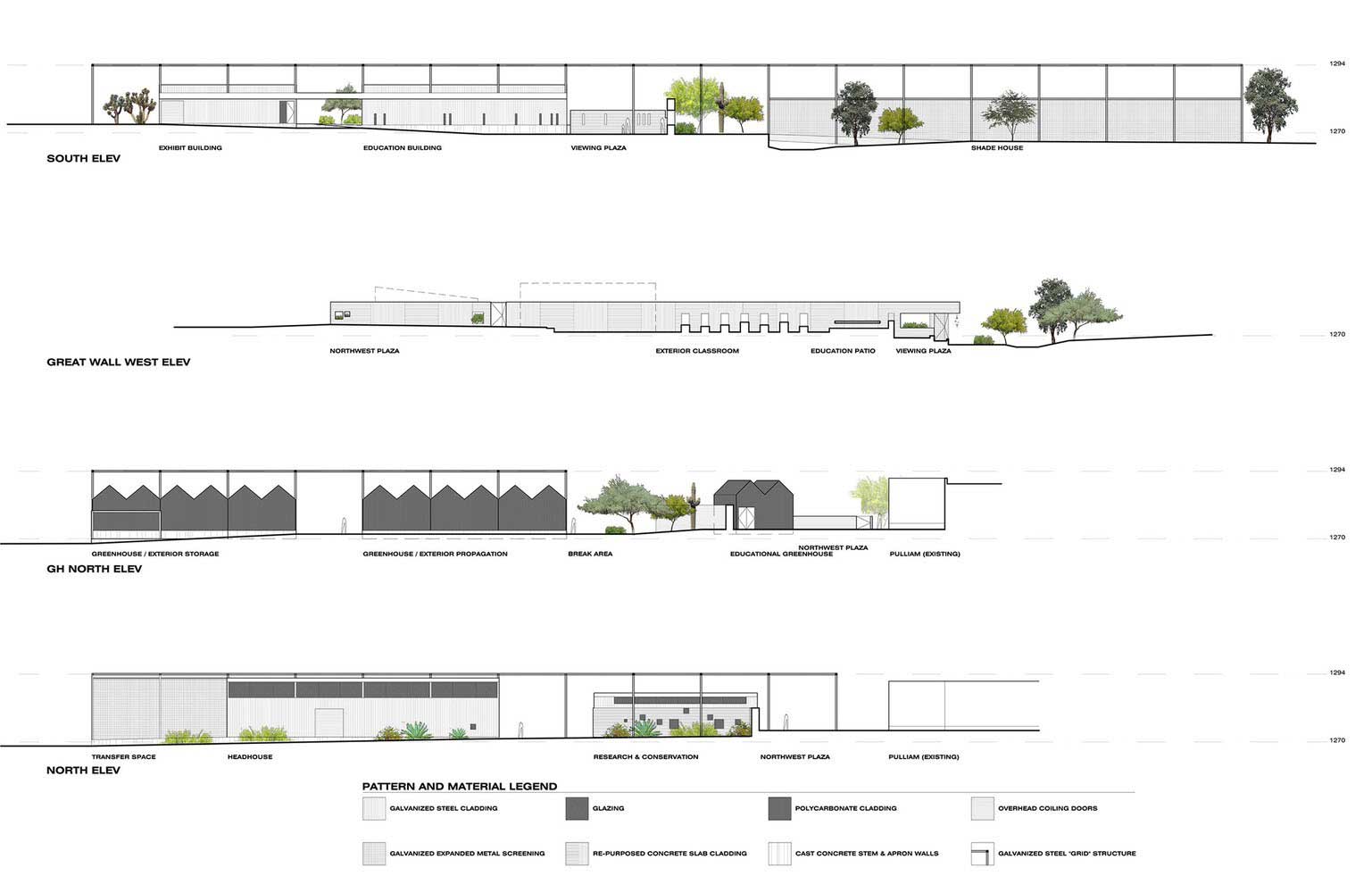

Walls and fences are typically used to keep people and areas separate, but at the Desert Botanical Garden an unusual series of structures actually brought people together. We combined wood, concrete, steel, stone and block to create a variety of richly textured and highly functional separators that both physically divided and visually connected open spaces. The Garden also needed a means to separate the “front of house” from “back of house” operations at the Horticultural Center, while allowing the public some degree of access and understanding of the building’s purpose and innovation. Many less interesting designs languished on the boards until Salenger conceived a Great Wall of boulders and gabions that were not only functional, but gave garden volunteers an opportunity to get involved as well. Each “toothpick boulder” was selected for its length and character – a full 1/3 of the boulder must be buried underground in order to support its own weight. While each rock was a different height, the tops were aligned by burying the boulders at varying heights, making the end result look much more effortless than it actually was. Over 436 tons of rock were brought down from a quarry in Kingman, and it took three weeks to set the 24 boulders in place. When the garden staff and construction crew started fondly naming the boulders endearing names like Porkchop, Sputnik, La Lengua and Little Horn, we knew that we’d helped forge a strong connection to the place. Tour guides now often point out the boulders by name as well, showing that lore and love of places isn’t just the domain of ancient history; history is happening today and will be enjoyed by future generations. Now the staff secretly call the Great Wall “HortHenge”, after the famous Neolithic earthworks of Great Britain. “I was proud to be able to work on excavation and selection of the boulders, and to determine how to place them. The Garden was open to new ideas and had the patience with us to work it out,” says project manager and architect Dusty Bodrero, AIA. “The Center’s project changed shape many times due to budget fluctuation,” he noted, so rallying garden volunteers helped contain the cost and aligned well with how the garden prefers to maintain its grounds. Because constructing the entire Great Wall out of massive boulders was going to be cost-prohibitive, space-filling interstitial zones of gabion baskets were lined with rock from the same quarry. Garden volunteers installed PVC irrigation pockets inside the gabions to create vertical gardens that simulated desert canyon microclimates that native species could happily cling to. Sustainability was one of the top touchstones of the project. Commercial construction can result in a lot of waste, and the 100-foot wash retaining wall was going to require a lot of wood formwork and stabilizing reinforcements. “If you can’t repurpose the formwork, it all just goes to the landfill. It’s no longer new lumber; it’s discolored, splattered with concrete, and it has holes in it,” explains 180 Degrees Design + Build Principal Architect John Anderson AIA. We decided to salvage the lumber and give it a new life as a texture along the four- foot courtyard perimeter fence, and to face the demonstration planters in the education center. An unexpected boon came in the form of free wood. Local corporation Intel provided two truckloads of wooden pallets formerly used to ship electronics. Where some might see landfill, we saw opportunity. Garden volunteers broke the pallets down into boards, then cut them to size for use in the fence and planters. “While Salenger was the design lead, we were brought in as a partner to share our expertise,” says Anderson. Because of our grasp of both design and building know-how, the Desert Botanical Garden realized that we’d give the project all the attention it deserved.

مدارک فنی