دهکدهی تاسفارونگا اثر گروه معماران دِیوید بِیکِر، نوشتهی لادن مصطفیزاده

دهکدهی تاسفارونگا

گروه معماران دِیوید بِیکِر (David Baker Architects) که به اختصار دی.بی.اِی (DBA) نامیده میشود، یک شرکت معماری مستقر در سانفرانسیسکو (San Francisco)، اُکلند (Oakland)، بیرمنگام (Birmingham) و آلاباما (Alabama) است که به ایجاد مساکن استثنایی، استراتژیهای خلاقانهی سایت، طراحی برای تراکم، و ادغام ساخت و سازهای جدید در قلمرو عمومی شناخته میشود.

گروه معماران دِیوید بِیکِر در سال 2010 با مشارکت گروههای دیگری چون گروه طراحی داخلی ماریا فیشر (Maria Fisher Interior Design)، گروه طراحی پی.جی.آی (PGA Design) دهکدهی تاسفارونگا (Tassafaronga) واقع در اُکلند، کالیفرنیا (California) را طراحی کرده است.

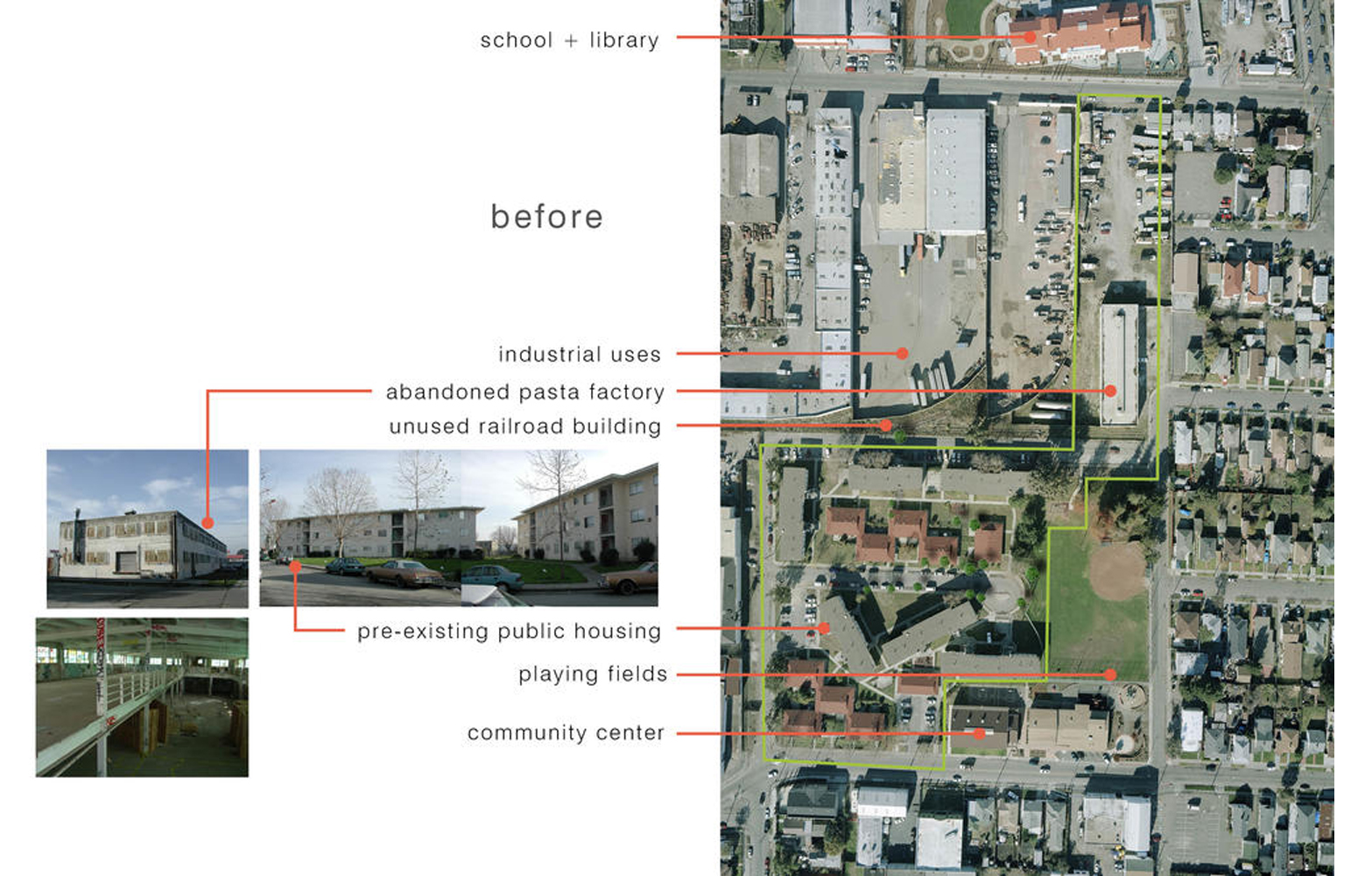

دهکدهی تاسفارونگا یک محلهی جدید است که تنوعی از مسکنهای مقرون به صرفه را در منطقهی محروم اُکلند به وجود آورد و در عین حال بافت فرسودهی محله را تعمیر کرد. این سایت یک براون فیلد (Brownfield)1 هفت و نیم هکتاری بود که شامل یک مسکن عمومی فرسوده، یک کارخانهی متروکه و ریل قطار بلااستفاده بود و یک محیط ناسالم را به وجود آورده بود. این پروژه که جایزهی اِی.آی.اِی کُت تاپ تِن (AIA Cote Top 10)2 را در سال 2015 به دست آورده، توانسته مسکنهای متنوعی با تراکم سه برابر منطقهی اطراف را ارائه دهد. هیئت داوران جایزهی اِی.آی.اِی کُت تاپ تِن (AIA Cote Top 10)، این چنین در مورد این پروژه صحبت میکنند:

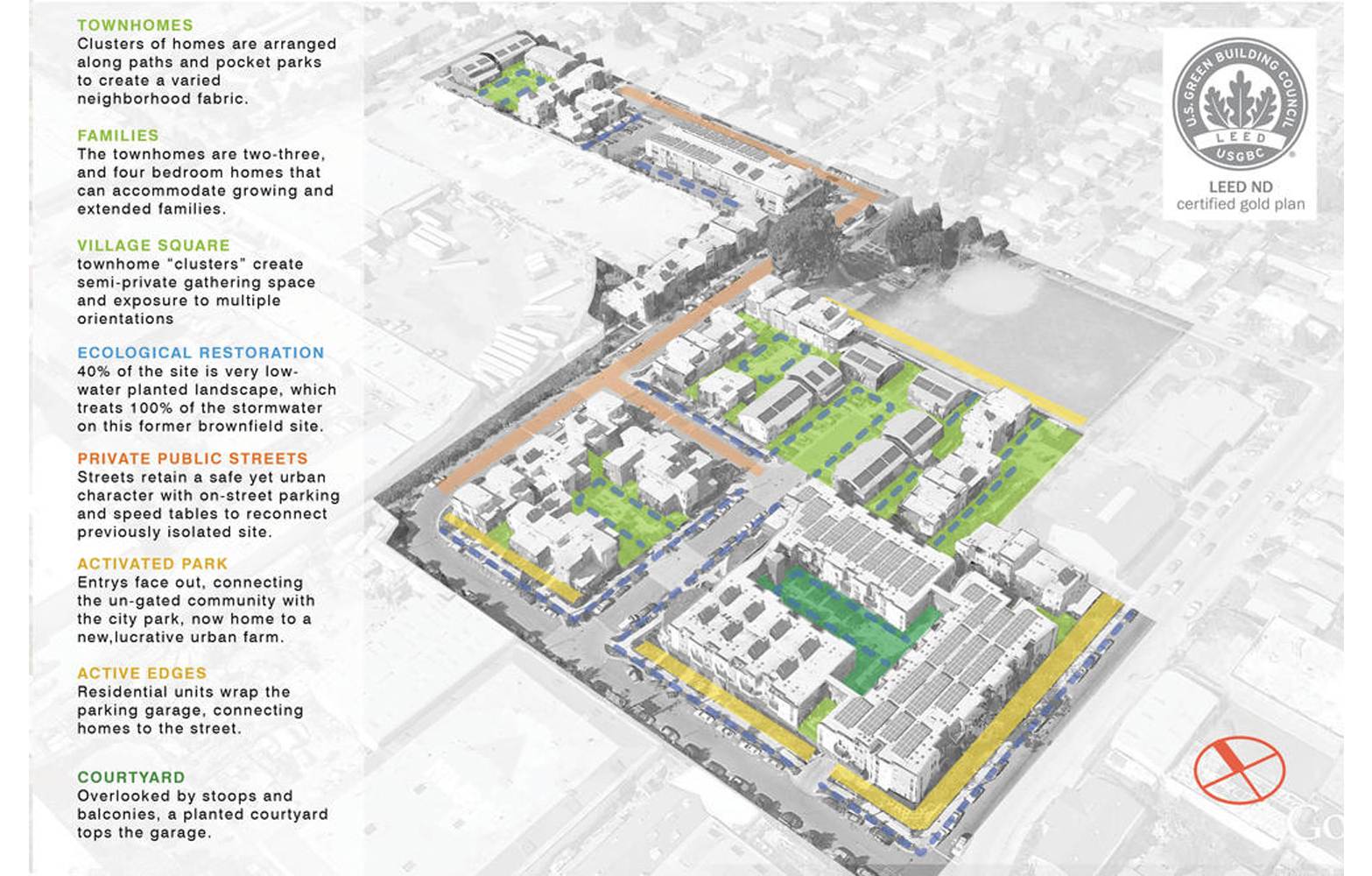

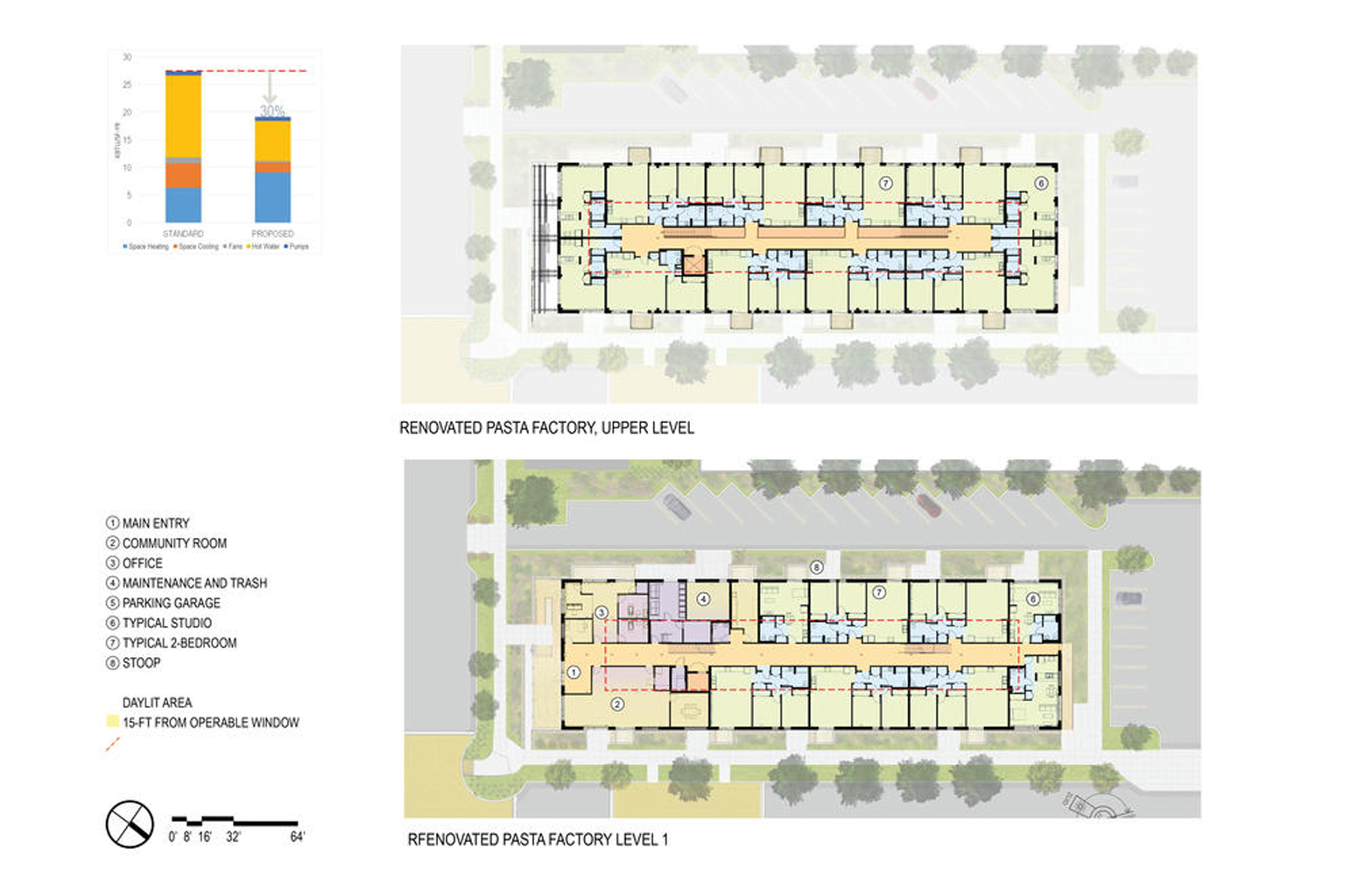

“این یک سایت صنعتی سابق است که به عنوان یک توسعهی مسکن مقرون به صرفه، تغییر کاربری داده است. استفادهی مجدد تطبیقی نوآورانه از کارخانهی ماکارونی سابق و یک استراتژی برای کاهش پارکینگ به منظور اولویت دادن به یک فضای بازی عمومی ایمن و نیمهخصوصی در آن وجود دارد. ما تنوع نوع خانه و مقیاس را تحسین کردیم. این پروژه ثابت میکند که بالاترین سطوح عملکرد زیستمحیطی را میتوان با بودجههای بسیار کم به دست آورد و در دستور کار طراحی قرار داد و این نشان میدهد که عملکرد بالا (زیستمحیطی) وارد جریان اصلی شده است. این پروژه یک نمونهی اولیه برای مسکن جدید در این جامعه را ارائه میدهد که شبیه یک پروژهی مسکن عمومی نیست. ما از کیفیت و تنوع استراتژیهای معماری و منظر قدردانی میکنیم. ما بهرهوری انرژی ساده همراه با سیستمهای فتوولتائیک روی سقف را دوست داریم. به نظر میرسد که این یک همکاری واقعی با یک معمار منظر است.”

توصیف پروژه

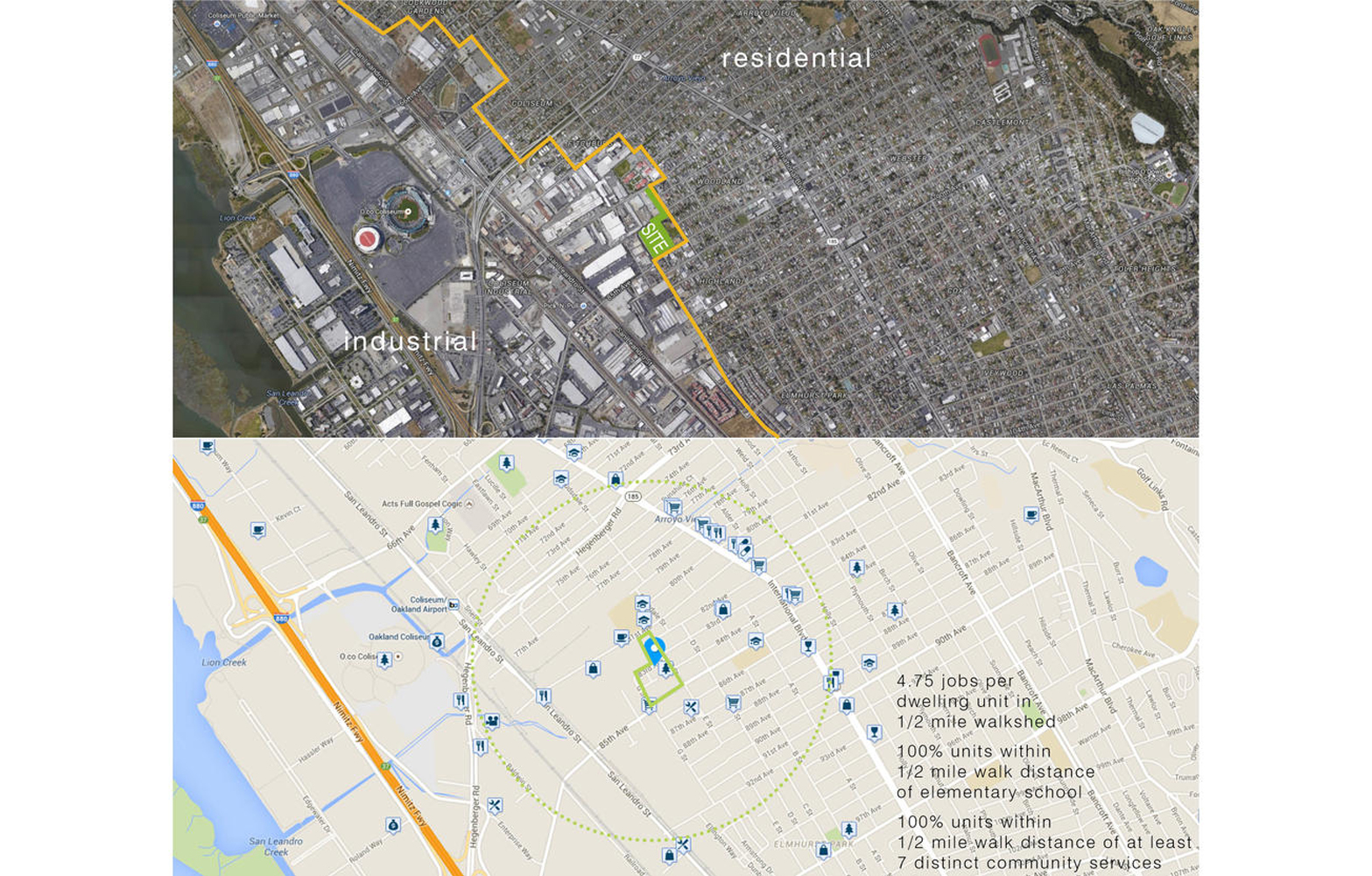

برای چندین دهه، تاسفارونگا یک براون فیلد بود که به آزبِست، سرب و حشرهکشهای سمی آلوده بود. در آن شرایط آسیبدیده، این مکان به محل یک پروژه مسکن تبدیل شد که تقریباً از محیط اطرافش جدا بود. اما اخیراً، تأمین مالی خلاقانه و استراتژیهای روشنگرانهی توسعهی محیط زیستی، تولد دوبارهی تاسفارونگا را به همراه داشته است. هفت و نیم هکتار از آن در یک بخش نادیده گرفته شده از شرق اوکلند به یک جامعه با درآمد مختلط تغییر یافته و به عنوان اولین پروژه در کالیفرنیا و یکی از اولین پروژهها در کشور برای دستیابی به گواهینامهی طلایی لید (Gold LEED-ND) احیا شده است. 157 واحد اجارهای جدید با استانداردهای گواهینامهی پلاتینیوم لید (Platinum LEED) ساخته شده است.

تاریخچهی تاسفارونگا به سال 1945 باز میگردد، زمانی که دولت ایالات متحده برای کارگران زمان جنگ در کارخانههای کشتیسازی اوکلند، مسکن موقت ساخت. همانطور که از نامش نیز پیداست، آلایندههای اصلی این سایت به این دوران مربوط میشوند.

این سایت در سال 1964 در اختیار ادارهی مسکن اوکلند (Oakland Housing Authority) یا اُ.اِچ.اِی (OHA) قرار گرفت و این سازمان، 87 واحد مسکونی عمومی (ساختمانهای بتنی کم ارتفاع و تاریک) را جایگزین سازههای اصلی کرد. این سایت توسط خیابانهای بنبست احاطه شده بود که آن را از محیط اطرافش کاملا جدا میکرد و به معنای واقعی کلمه، حصارکشی شده بود. تاسیسات صنعتی در غرب سایت و محلهای آسیبدیده از خانههای کوچک و تکخانواری در شرق آن قرار داشتند و تاسفارونگا به محلی برای پرورش مواد مخدر و جنایات گروهی تبدیل شده بود. بریجت گولکا (Bridget Gulka) یکی از مدیران ارشد برنامهی پیشنهاد شده توسط اُ.اِچ.اِی (OHA) که به تحولات اخیر تاسفارونگا کمک کرده است، میگوید:

” ما 10 سال پیش سعی کردیم آن را احیا کنیم، اما این کار مؤثر نبود. شکافهای عمیق در بتن و مسائل لرزهای به وخامت سناریو افزوده شد. اُ.اِچ.اِی (OHA) در سال 2007 مجوز تخریب این پروژه را گرفت و در طرح جدید از ابتدا، رویکردهای پایدار برای تخریب، ساختوساز، برنامهریزی سایت و عملکرد مستمر در اولویت قرار گرفتند.”

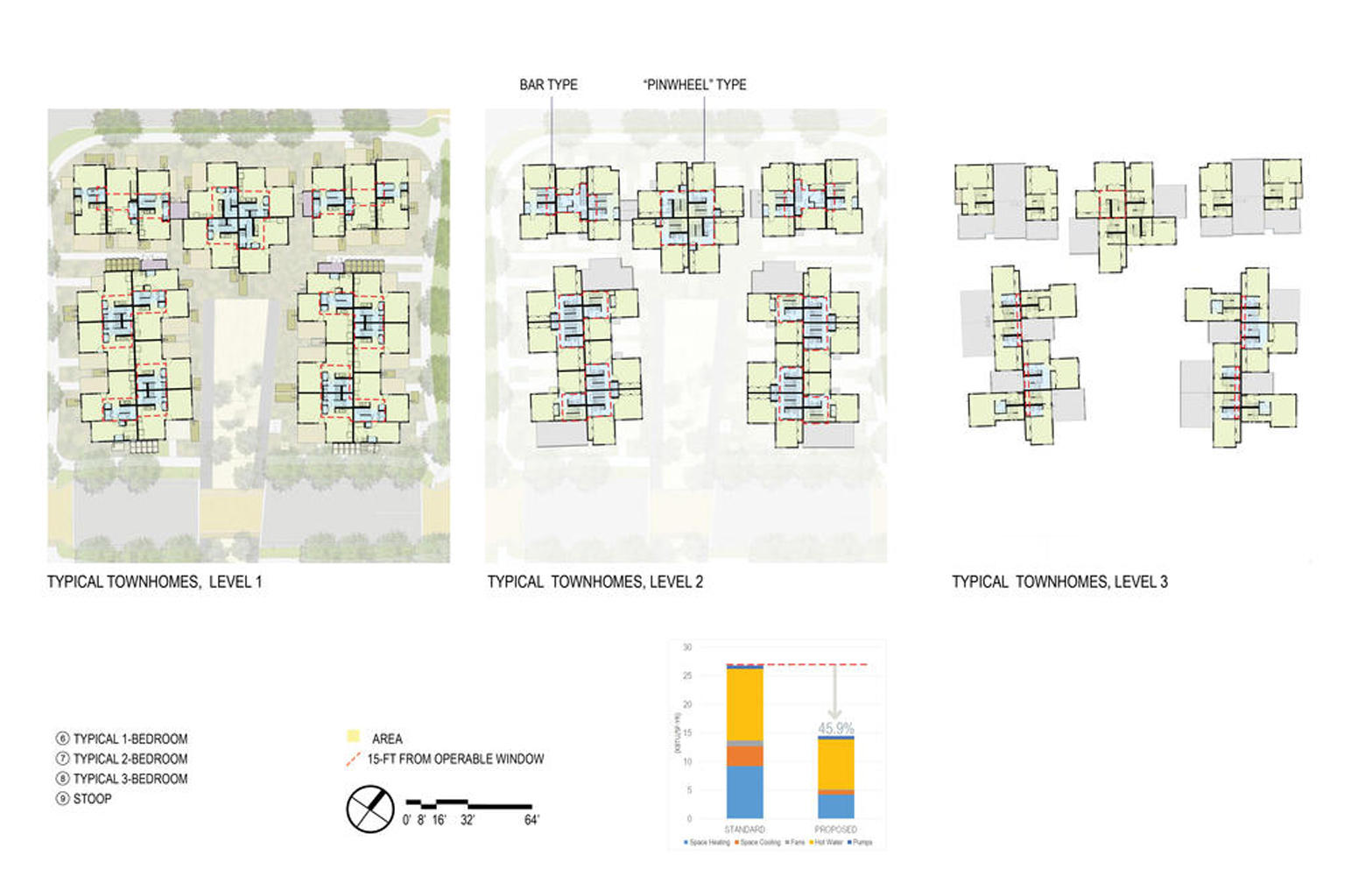

اداره مسکن اوکلند در سال 2005 شروع به برنامهریزی برای بازسازی سایت با واحدهای پرتراکم، در دسترس و کم مصرف برای خانوارهای کم درآمد و ایجاد محیطی مناسب برای عابران پیاده کرد که مرزهای صنعتی را نرم کرده و ارتباطات ایمن با امکانات محله ایجاد کند. دهکدهی جدید دارای مسکنهای متنوع با تراکم سه برابر منطقهی اطراف است؛ شامل یک ساختمان آپارتمانی 60 واحدی مقرون به صرفه،77 خانهی مقرون به صرفه برای اجاره و 20 آپارتمان حمایتی با کلینیک پزشکی، به علاوه 22 خانهی دیگر نیز در سایت ادغام شد. مسیرهای محوطهسازیشده و جادههای آرامشده ( از نظر ترافیکی) اکنون به راحتی خانه را به کتابخانهی قبلی، مدرسهی محلی، پارک شهر و مرکز اجتماعی متصل میکند.

طراحی و نوآوری

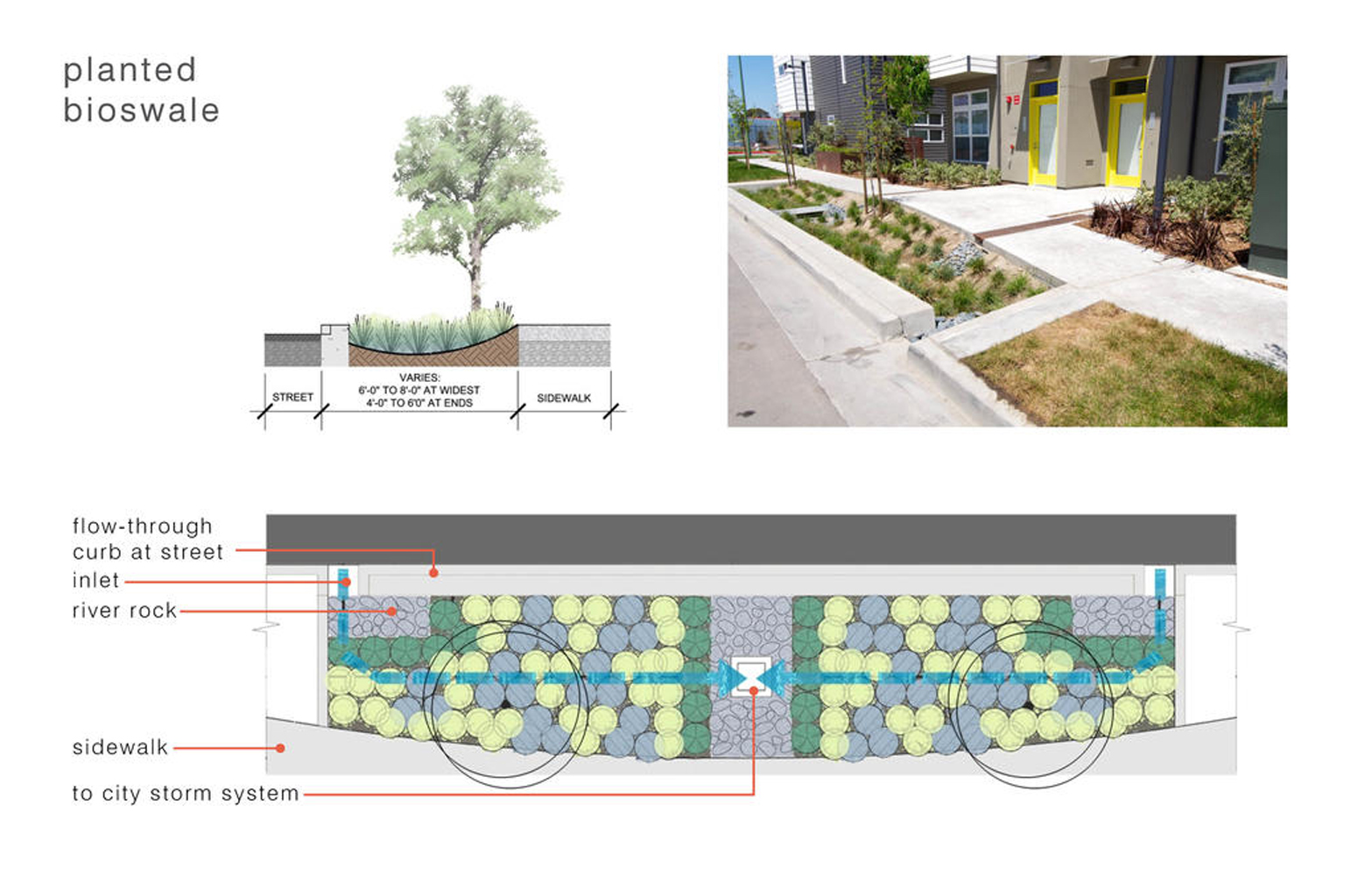

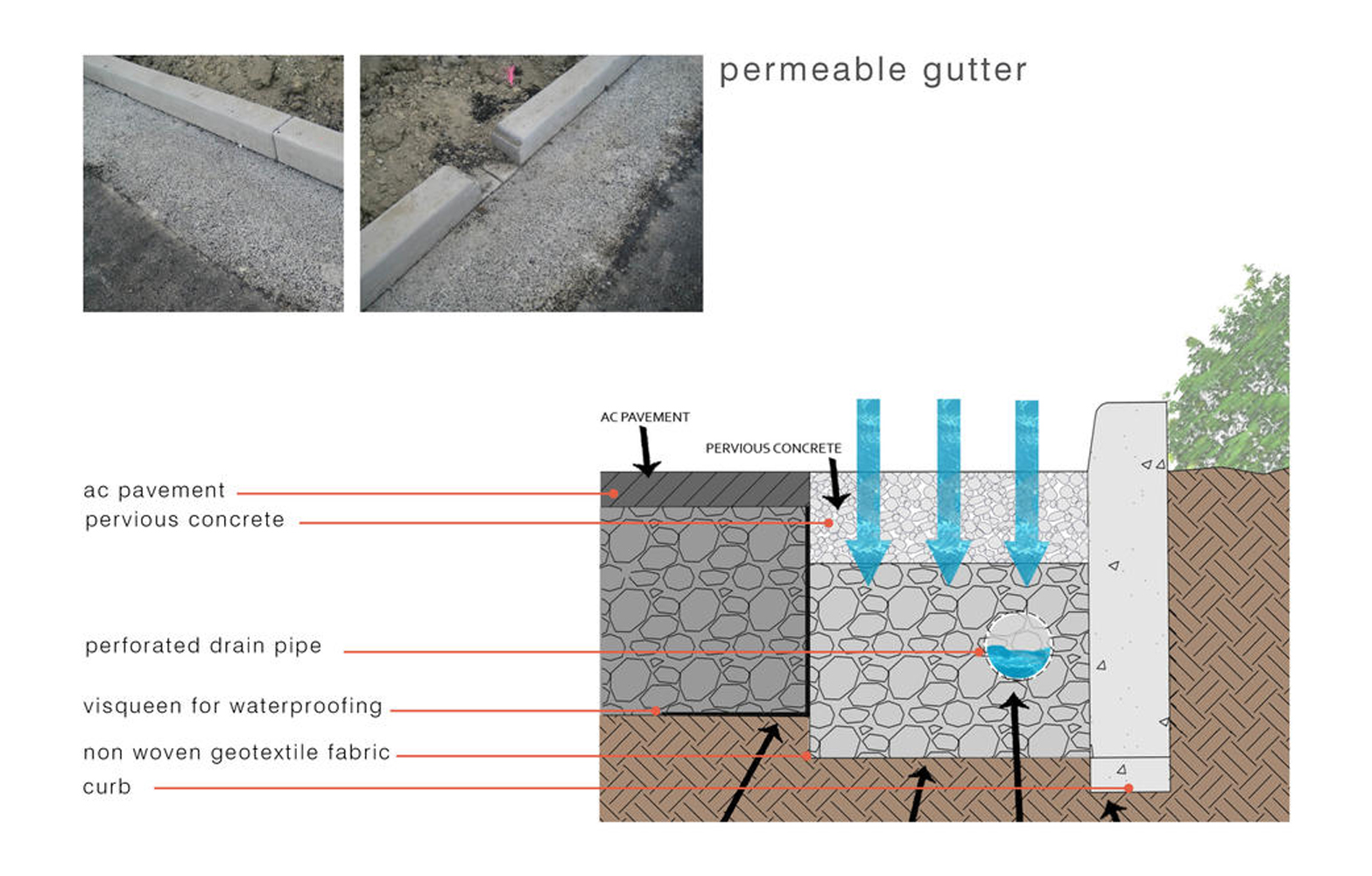

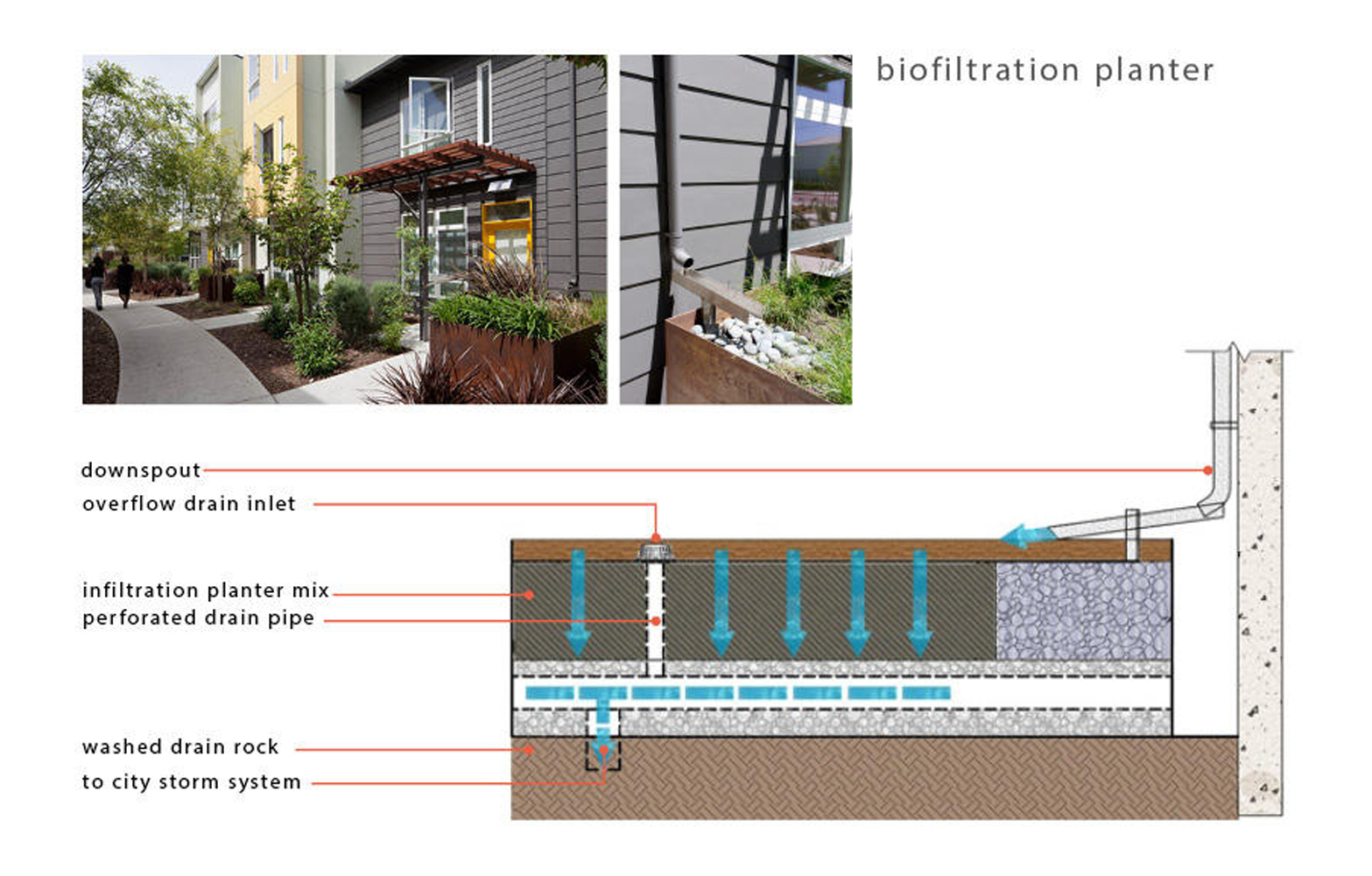

طراحی در این سایت به سه هدف صورت گرفته است؛ تقویت بافت شهری موجود، افزایش کیفیت زندگی و رسیدن به بالاترین سطح پایداری. طرح ارتباط منسجمی بین محیط صنعتی و کاربری مسکونی به وجود آورد و تقویت محله توسط پانزده دسته از ساختمانهای وابسته به یکدیگر با شبکهای از خیابانها و مسیرهای ایمن به وجود آمد؛ در قسمتهای خصوصی، خیابانها به عنوان گذرگاههای عمومی، جامعه را با محله یکپارچه میکنند؛ تمام خانهها مستقیما به وسیلهی ورودی و یا به لحاظ بصری به خیابان متصل میشوند و از این طریق “چشمان خیابان (Eyes on the Street)3” افزایش مییابد. با توجه زیاد به مقیاس و جزئیات ساختمانها، منظرهای ارگانیک از نظر گونهشناسی با محلهی اطراف ایجاد شد.

پینوشت

- براون فیلد (Brownfield) به طور کلی به قطعه زمینی اطلاق میشود که قبلاً برای مقاصد صنعتی استفاده میشده است و ممکن است با غلظت کمی از مواد شیمیایی خطرناک آلوده شده باشد.

- جایزهی اِی.آی.اِی کُت تاپ تِن (AIA Cote Top 10 Awards) یکی از شناخته شدهترین جوایزی است که برای تعالی طراحی پایدار ارائه میشود و هر سال، ده پروژهی نوآورانه را به دلیل ادغام طراحی با مسائل زیستمحیطی معرفی میکند.

- چشمان خیابان (Eyes on the Street) از نظریاتی است که توسط جین جیکوبز (Jane Jacobs) روزنامهنگار آمریکایی مطرح شده است و بر اساس این نظریه، جمعیت بیشتر در خیابانها به معنای محلههای امنتر ست. جین جیکویز میگوید:

“باید چشمها به خیابان باشد، چشمهایی متعلق به کسانی که میتوانیم آنها را مالکان طبیعی خیابان بنامیم. ساختمانهای موجود در یک خیابان که برای رسیدگی به افراد غریبه و تضمین ایمنی ساکنان و غریبهها مجهز شدهاند، باید به سمت خیابان طراحی شوند.”

معماری معاصر جهان: محلهی مسکونی

_______________________________________

نام پروژه: دهکدهی تاسفارونگا

عملکرد: مختلط

شرکت-دفتر طراحی: گروه معماران دِیوید بِیکِر

مساحت زمین: 238,000 فوت مربع

تاریخ شروع و پایان ساخت: 2010

Tassafaronga Village by David Baker Architects

Project Name: Tassafaronga Village

Function: Mixed Land Use

Architects: David Baker Architects

Area: 238,000 square feet

Year: 2010

For decades, Tassafaronga, in Oakland, California, was a brownfield, tainted with asbestos, lead, and toxic insecticides. In that blighted condition, it became the site of a hardscrabble housing project, a place segregated, virtually disconnected, from its surroundings. But recently, creative financing and environmentally enlightened development strategies have brought about Tassafaronga’s rebirth (really, its reincarnation). Its 7.5 acres, in a neglected section of East Oakland, have been transformed, emerging as a vital mixed income community the first project in California and one of the earliest nationwide to achieve Gold LEED-ND plan certification And within that reclaimed community, the 157 new rental units have been built to Platinum LEED-Home standards. The saga of Tassafaronga goes back to 1945, when the U.S. government developed the land, erecting temporary housing for wartime workers in Oakland’s shipyards. The site’s prime contaminants date from this era-as does the name, honoring a South Pacific World War II battle of dubious distinction. In 1964, after the Oakland Housing Authority (OHA) acquired the property, it replaced the original structures with 87 public housing units: grim low-rise concrete buildings in a barren hardscape. Literally fenced in, and choked off by dead-end streets, it stood isolated from its adjacencies: industrial facilities to the west, and to the east, a battered neighborhood of small, cheek-by-jowl, single-family homes. Tassafaronga Village, as the project was quaintly and optimistically christened, devolved into a breeding ground for drug and gang crime. “We tried to revitalize it 10 years ago, but that didn’t work,” says Bridget Gulka, an OHA senior program manager who helped spearhead Tassafaronga’s recent transformation. Deep fissures in the concrete and seismic issues added to the deteriorating scenario. In 2007, OHA se cured permission to demolish the project, officially deemed “severely distressed.” From the start, says Gulka, sustainable approaches to demolition, construction, site planning, and ongoing function were a priority.

says Gulka, “but we were striking out securing federal funds.” After coming up empty with HOPE VI, the US Department of HUD’s program to revitalize destitute public housing, OHA took a leap, approaching Tassafaronga in a new role: as a non-profit developer. As she recalls, “we’d worked with enough of them to learn the ropes.” To raise capital without a big federal grant, OHA took the controversial step of persuading HUD to swap the public housing units for project-based Section 8 federal subsidy vouchers. “The same level of subsidy for the same income group,” says Gulka, “but the key difference: now we could take the vouchers to the bank and get a loan.” Unlike public housing, which remains in the low-income sector virtually in perpetuity, these Section 8 vouchers only guarantee the housing to this demographic for 30 years—via a 15-year federal contract with a 15-year renewal extension though additional extensions are certainly possible. OHA raised more than $23.5 million in tax-credit equity for this $75 million project (and, according to Gulka, all tenants in good standing from the demolished buildings had first dibs on moving back). To reenvision Tassafaronga, OHA hired David Baker + Partners, San Francisco architects experienced with social, environmental, and housing issues. Where competing firms called to demolish the pasta factory at the site’s north end, Baker proposed reusing it adaptively, bridging the divide between residential and industrial adjacencies. Today, Tassafaronga Village, with colorful new buildings clad in stucco and fiber-cement board, weaves together diverse housing types and income levels, from very low to moderate. Unlike the monotonous 1960s design, these forms are richly varied, bringing together new structures a 60-unit, three-story apartment building and 77 units in two-and three story townhouses with the ex-pasta factory, now housing 20 lofts and a medical clinic. Habitat for Humanity is erecting 22 affordable, for sale townhomes here, designed by Baker with construction fueled by homeowner sweat equity. In its aspirations to lift the entire community’s pride and culture through social and physical diversity, Tassafaronga reflects the influence of HOPE VI, with its New Urbanism and Defensible Space planning principles. That model’s emphasis on walkable, high-density communities, punctuated by pocket parks connecting to the surroundings without sprawl-dovetailed with the goals of LEED-ND, emerging as a pilot program just as Tassafaronga headed into design. By cleverly acquiring a small, land locked triangle of undeveloped property and swapping land with neighbors to square off awkward parcels, OHA reconnected to neighborhood streets and gave new life to a formerly dangerous back alley. Advocating the crime-deterrent benefits of “positive pedestrian flow,” the designers fronted the buildings on streets and paths wherever possible. Such quiet, crime-reducing design moves (albeit supplemented by hidden surveillance cameras) replaced gates and fences. The reconfigured thoroughfares are traffic calming: relatively narrow and now with pedestrian sidewalks. Lush swales green the route, while achieving 100 percent site storm-water remediation. Tassafaronga has benefited from two new elementary schools and a previously languishing park along its borders, helping re-knit the site’s edges into the larger context. According to the LEED-ND scoresheet, this project scored high for its brownfield clean-up and reuse, urban location, reduced automobile dependence and reliance on bus lines), energy and water efficiency, proximity to jobs and schools, and housing affordability and diversity. Though Tassafaronga’s Walk Score hovers below average for Oakland, ideally, the community will catalyze growth in nearby retail. Though the nearly one-mile route to the closest Bay Area Rapid Transit station is not optimal, a defunct rail spur could eventually provide a green bike/pedestrian link to it. Tassafaronga’s rental buildings are all poised for LEED Platinum certification, but budget-driven trade-offs produced variation in sustainable features across its housing types. (Though Habitat may not pursue LEED certification for its 22 homes, Baker’s firm also designed them with attention to the environment.) Only the apartment building includes a green roof. And while all 157 rental units provide solar-heated water, only the Habitat and apartment buildings have PVs to generate electricity. With sensor controls, tenant education, and other measures, Tassafaronga’s energy usage remains 20 to 30 percent below California’s progressively stringent code. Exemplary in yet another way, the ex-pasta factory reuses everything from the concrete shell, wood framing, and roof to concrete floors (ground, sealed, and polished) and structural steel (supplemented for seismic codes). Several months since opening, Tassafaronga is bright, well maintained, and fully occupied. Green gathering spaces balance built form. Individual garden plots are producing vegetables, and repurposed cattle-feeding troughs in the plazas burgeon with native, water-efficient plantings. “Sustainability isn’t necessarily about green bling,” says project architect Daniel Simons. “Here, efficiency came through lots of practical and small moves done carefully-from good insulation and thermal break windows to dual-flush toilets and low-flow fixtures. Not all glamorous.” Baker agrees: “The future is about paying attention—the sum of many little things.”

مدارک فنی

منابع و ماخذ

- Green Source, the magazine of sustainable design, 2011

- www.dbarchitect.com

- www.architectmagazine.com

- www.sciencedirect.com

- www.aia.org

- www.aiatopten.org

- medium.com