خانهی غیرفعال

بسانکورت، فرانسه، ترجمهی الناز شمالی

پایداری

PASSIVE HOUSE

Bessancourt, France

مهندسان

سولارس باوئن (Solares Bauen) طراحی حرارتی، دای آیزنهاور (DI Eisenhauer) و فیلیپ بوشه (Philippe Buchet) طراحی ساختاری

غیرفعال پیشرونده

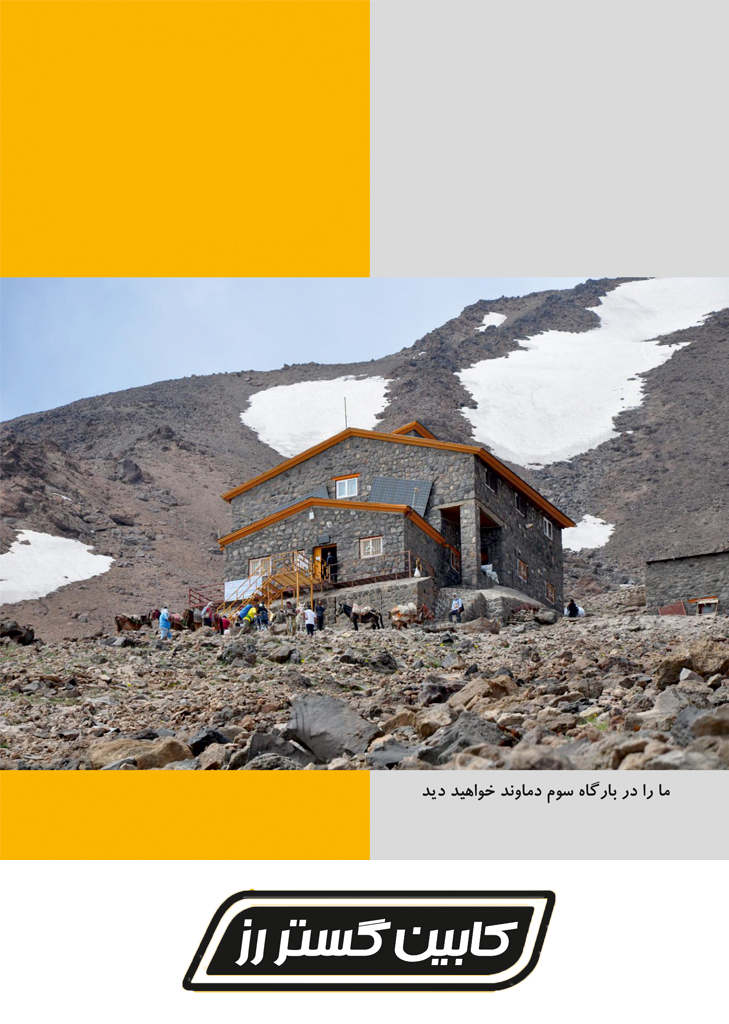

خانهی غیرفعال با پوشش بامبو که خارج از پاریس قرار دارد سنتهای را زیر پا میگذارد.

خانههای غیرفعال، به منظوره بهرهوری دقیق از انرژی و همچنین کاهش آسیبهای زیستمحیطی ساخته میشود. این ساختمانها انرژی بسیار اندکی مصرف میکنند و نیاز به انرژی چندانی برای گرمایش یا سرمایش فضا ندارند.

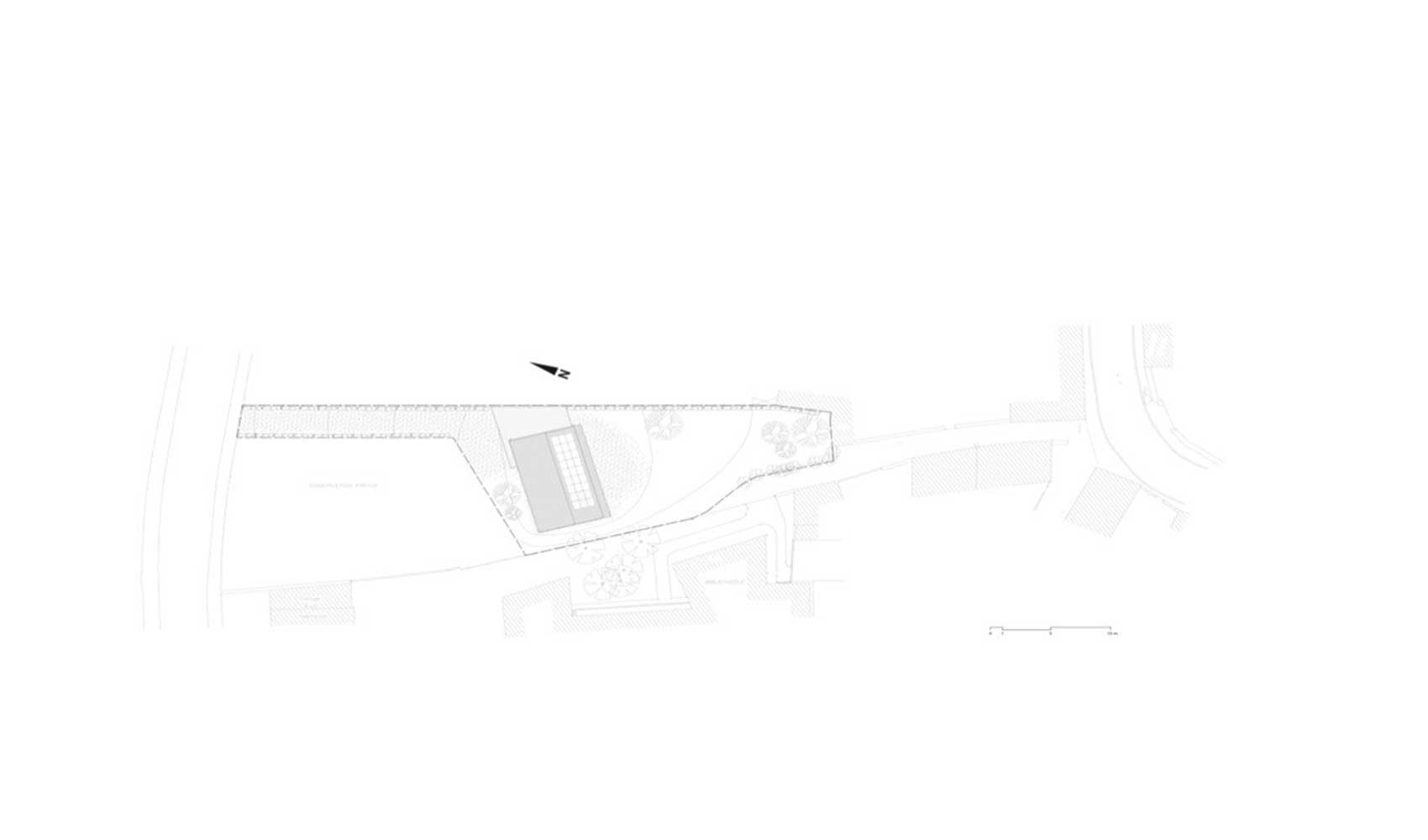

خانهی غیرفعال با پوشش بامبو اثر معماران میلنا کارانشوا (Milena Karanesheva) و میشا ویتزمن (Mischa Witzmann) در بسانکورت 30 کیلومتری شمال غربی پاریس گردشگران حوزهی معماری، مردم محلی، عوامل تولید فیلم و افراد عادی را به خود جذب کرده است. این سازه در منطقهای خودنمایی میکند که عمدتاً سازههای قرن دوازدهم و سیزدهم در امتداد خیابانها و حیاطهای متراکم و باریک آن دیده میشود. به همان اندازه که ساخت چنین خانهای در یک منطقه تاریخی با اقامتگاههای کوچک متعلق به دهههای 70 و 80 غیرممکن به نظر میرسید به همان اندازه ساخت آن چالش برانگیز بود اما ایدهی ساخت خانههای غیرفعال را در این کشور رواج داد.

ساخت این بنا در سال 2009 به پایان رسید و به طور رسمی خانهی غیرفعال نامگذاری شد که دومین خانه در فرانسه و اولین در پاریس بود. تا آن زمان، کارانشوا و ویتزمن زوجی که شرکت معماری کاراویتز را در سال 2005 در پاریس تأسیس کرده بودند، حدود هفت خانهی غیرفعال را طراحی کردند. در فوریهی همان سال کاراویتز به دنبال مجوز ساخت یک آپارتمان در پاریس بود که طبق اصول خانهی غیرفعال طراحی شده بود.

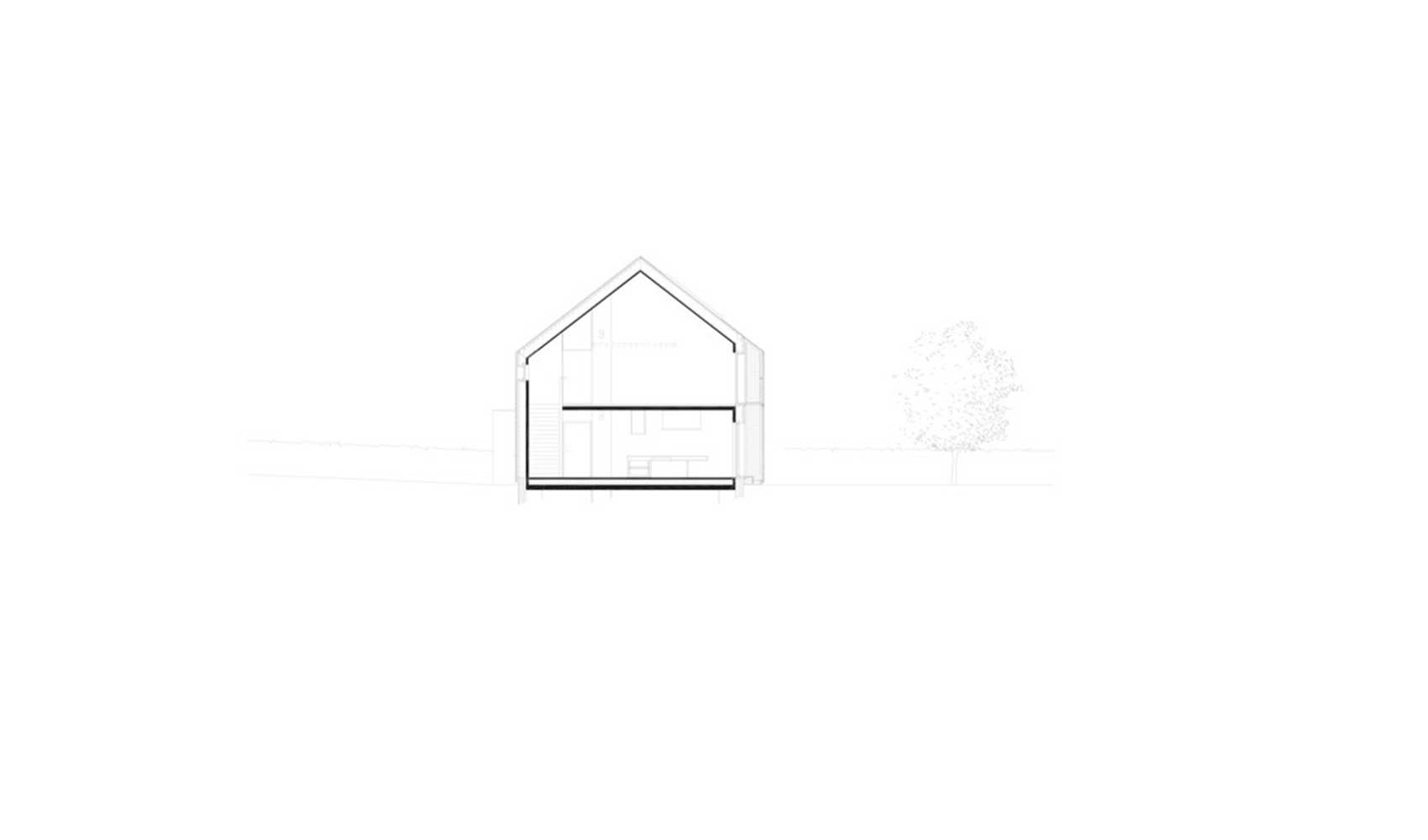

طبق توضیحات کارانشوا این سازه با مساحت 177 متر مربع به دلیل قوانین سختگیرانه شهرسازی از نظر فنی بسیار ساده است. در این سازه از سقف شیبدار و پنجرههای محدود استفاده شد تا حریم شخصی حفظ شود. کارانشوا میگوید: “ما معماران سبک مدرن هستیم نه قرن هیجدهم. برای ما بسیار مهم بود که این بنا را مدرن بسازیم.” او و ویتزمن با انتزاعیسازی فرم سنتی به هدف خود رسیدند.

>پارامترهای کلیدی

موقعیت بسانکورت، فرانسه (آبخیز رود سن)

مساحت 177 مترمربع

قیمت 377900 دلار

تاریخ اتمام سپتامبر 2009

مصرف انرژی سالانه (بر اساس شبیهسازی)

110 مگاژول بر مترمربع

ردپای کربنی سالانه (پیشبینی شده)

5 کیلوگرم کربن دی اکسید بر متر مربع

برنامه اتاق خواب، آشپزخانه، حمام، اتاق نشیمن و گاراژ

> گروه

مالک، معماران و طراحان داخلی

دفتر معماری کاراویتز (Karawitz Architecture)

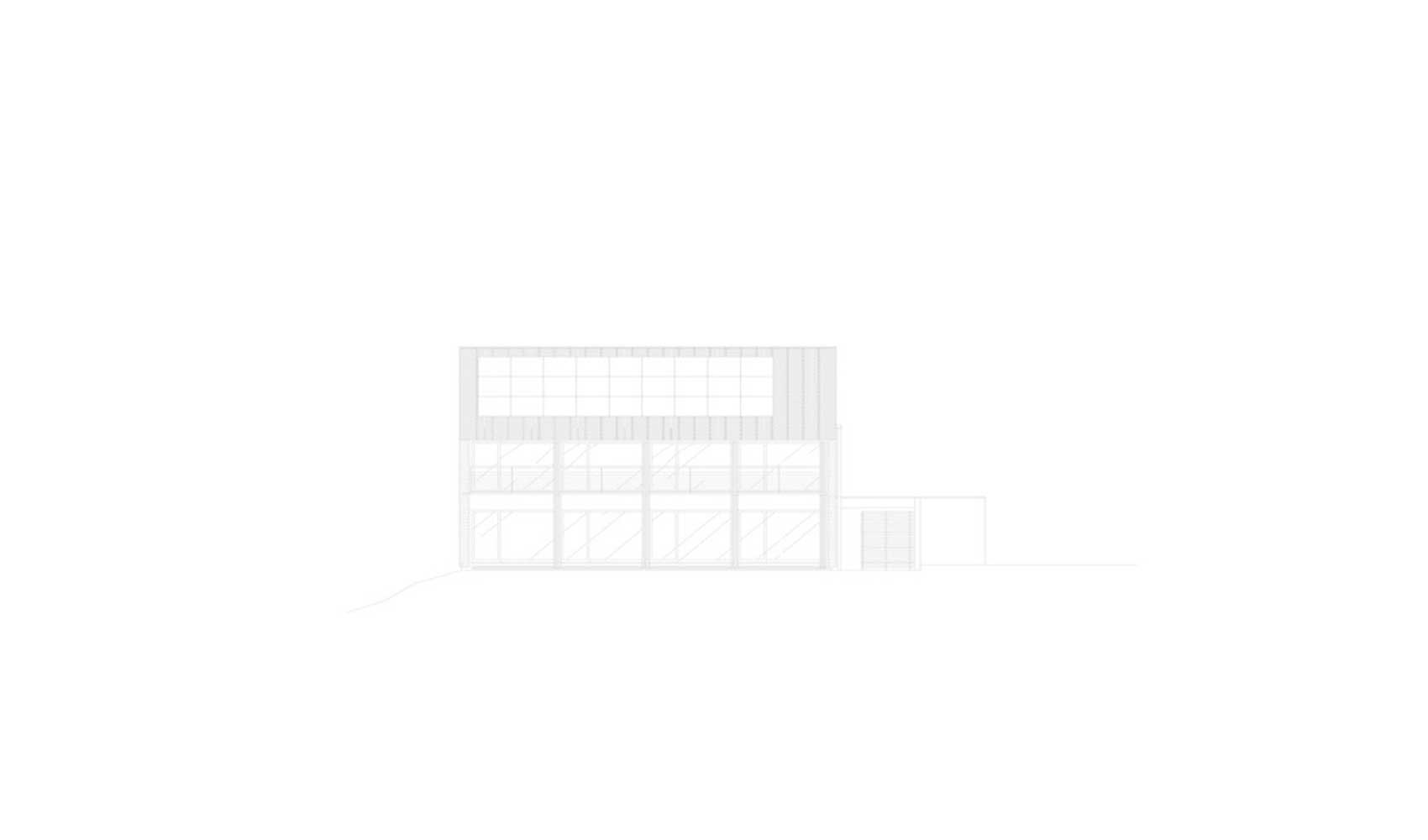

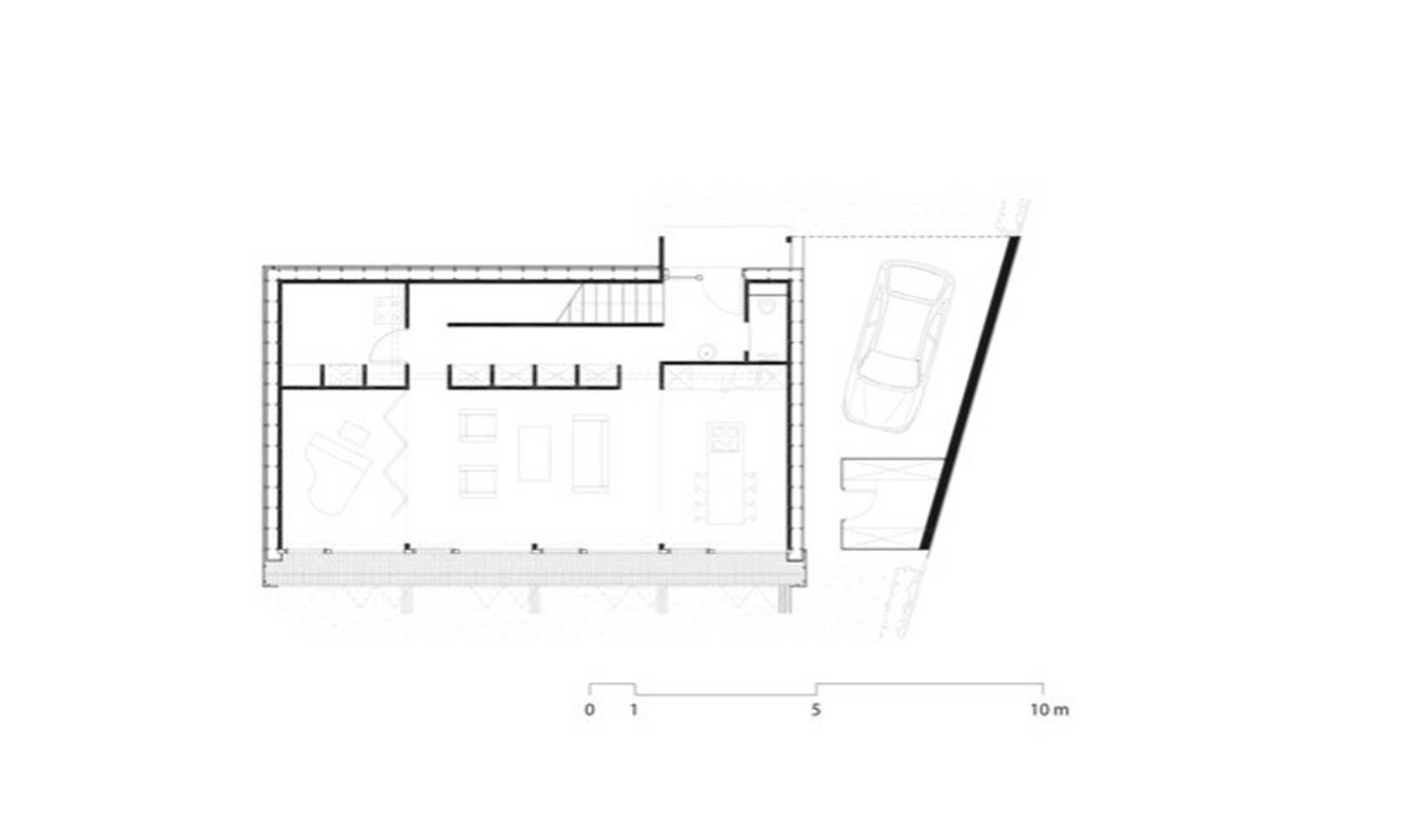

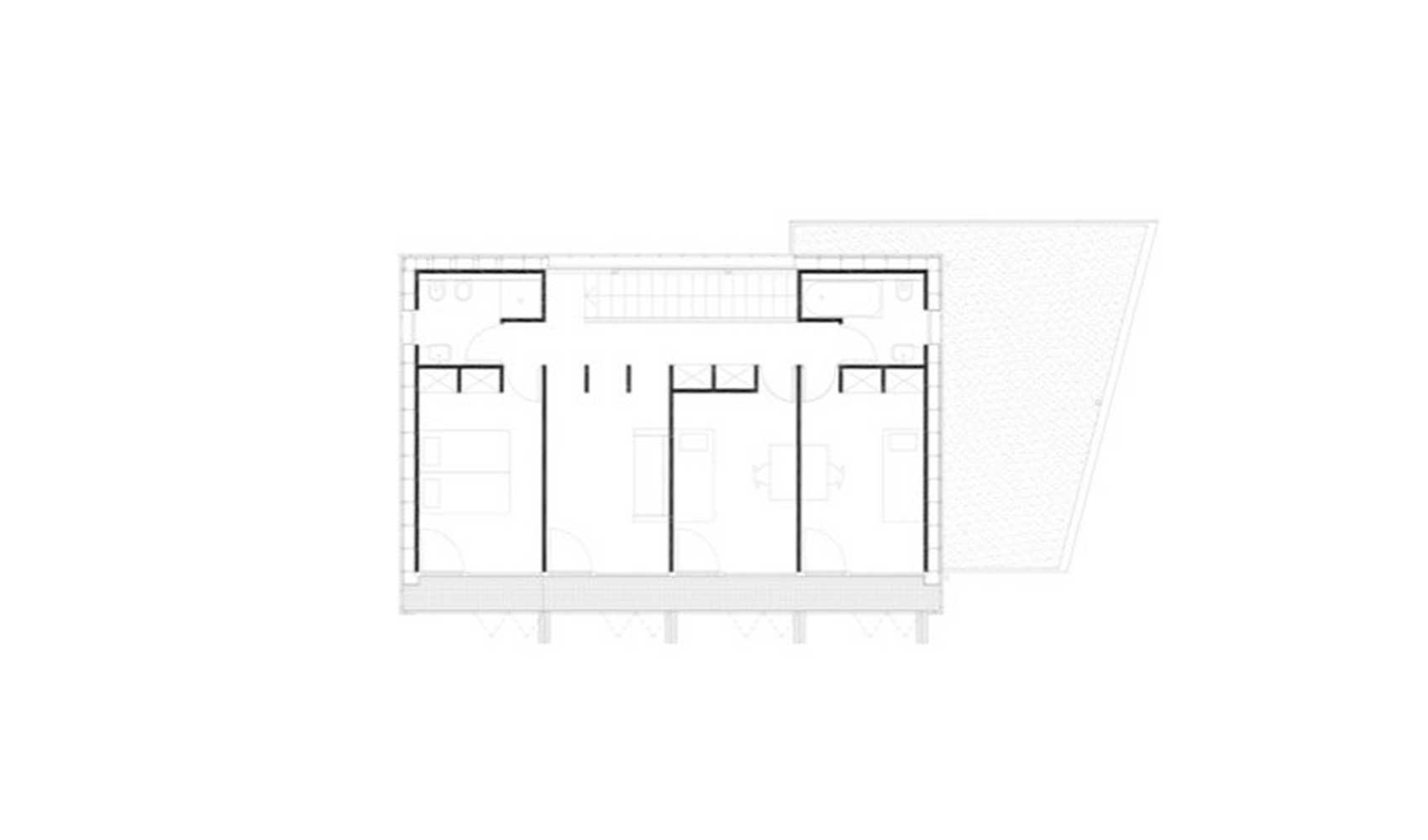

یک دیوار اساسی تقریباً 60 سانتی، مستطیل ساده را به دو قسمت تقسیم میکند. در قسمت جنوبی خانه که مساحت آن دو برابر قسمت شمالی است بیشتر پنجره کار شده است. آشپزخانه و اتاق نشیمن در طبقه همکف و سه اتاق خواب و فضای بازی طبقه دوم رو به جنوب است. حمام و رختشویخانه رو به شمال است. دیوار اساسی هم به عنوان دیوار باربر عمل میکند و هم ابزارهای مکانیکی را پنهان میکند. یک گذرگاه مشبک فلزی در نمای جنوبی طبقه دوم نقش بالکن را ایفا میکند و از کرکرههای پنجره پشتیبانی میکند.

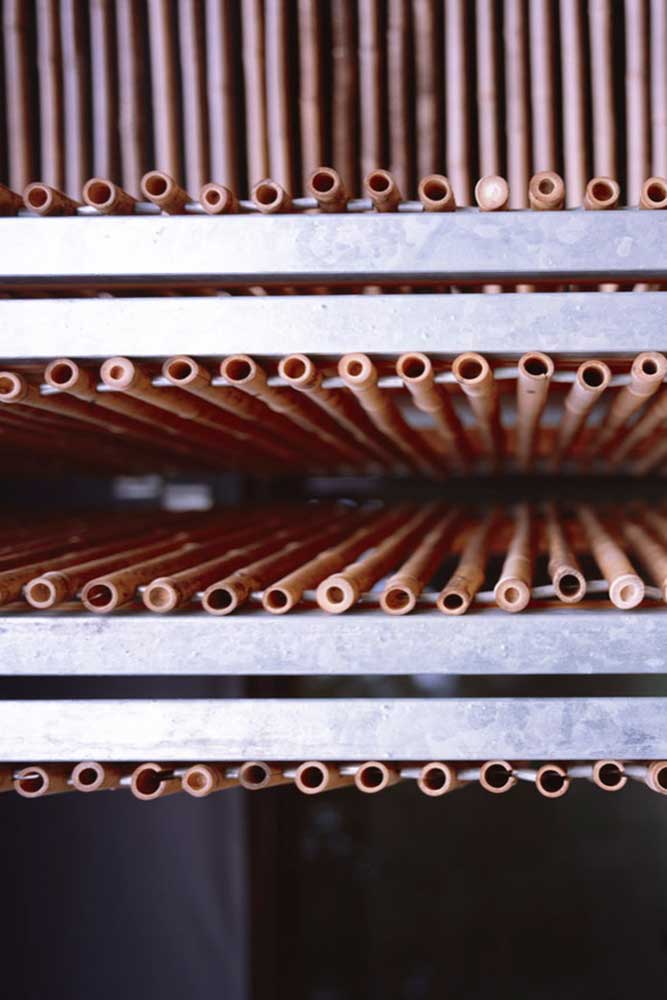

کارانشوا و ویتزمن پس از بررسی دهها نوع روکش چوبی، بامبو را به دلیل داشتن روزنههای هوایی و بی نظمی بافت آن انتخاب کردند. از آنجایی که خانه جمع و جور بود، مهم بود روکار دیوار بسیار روشن باشد.” در اروپا، پروژههای محدودی با استفاده از بامبو کار شده است، و پوشاندن خانه با ساقههای توخالی به آن اصالت میدهد و همچنین از چوب ارزانتر است.

با این حال، سادگی نسبی خانه، مشکلات فنی و درگیریهای اداری که معماران با آن روبرو بودند را نشان نمیداد. کارانشوا بلغارستانی و ویتزمن اتریشی بودند و با مفاهیم خانهی غیرفعال آشنایی داشتند. گواهینامه عملکرد پس از ساخت خانههایی در سراسر آمریکای شمالی در طول بحران نفت دههی 1970 به وجود آمد و در سال 1996 زمانی که دکتر ولفگانگ فیست (Wolfgang Feist) موسسهی خانهی منفعل (PassivHaus Institut) را در آلمان تاسیس کرد رسمی شد.

اما زمانی که معماران به دنبال کارفرما برای تامین مالی نمونهی اولیهی این سازه در فرانسه بودند، با شک و تردید در مورد عملکرد چنین سازهای و گاهاً خندهی آنها مواجه شدند. کارانشوا میگوید: «این ناامیدکننده بود.» در همان زمان، نیازهای خانوادگی خودشان در حال تغییر بود و آنها تصمیم گرفتند این خانه را برای خود بسازند.

کارانشوا ادامه میدهد: «موقعیت سازه خیلی برای ما مهم بود چون نمیخواستیم از خودروی شخصی استفاده کنیم و ترجیح میدادیم نزدیک ایستگاه راه آهن محلی و امکانات رفاهی دیگر باشد.» یک نقطه با جهتگیری خوب درست پشت کلیسای متعلق به قرن دوازدهم بود، اما یک نهاد تصمیمگیرندهی محلی که مسئول حفاظت از بناهای تاریخی بود در ابتدا در برابر طرح کاراویتز مقاومت کرد. بامبو؟ فتوولتائیک؟ قطعاً نه. پس از مذاکرات فراوان، بدبینی این نهاد به حمایت تبدیل شد، اما به طور کامل از موضع خود عقبنشینی نکردند. (حتی شهردار محلی هم طرفدار پروژهی آنها شد.)

به طور همزمان، کارانشوا و ویتزمن مجبور شدند به دنبال نجارانی باشند که در ساخت خانههای غیرفعال تجربه داشته باشند که در فرانسه، جایی که بیشتر سازهها از سنگ ساخته بود بسیار دشوار بود. خوشبختانه با کمک یک نجار از برتانی (Brittany) و یک شرکت مستقر در پاریس که متخصص در ساخت و ساز پایدار بود توانستند با موفقیت این پروژه را به اتمام برسانند.

کارانشوا میگوید: «ما فکر میکردیم، خانه بدون سیستم گرمایشی ممکن نیست، اما من تعجب کردم که چقدر راحت است». زمانی که هوا آفتابی است، دمای خانه تنها با 0.48 تغییر هوا در هر ساعت به سرعت افزایش مییابد و نرخ بازیابی حرارت 76 درصد است. همچنین معماران بسیار خوش شانس بودند، زیرا یک شرکت محلی به تازگی شروع به عرضهی پنجرههای سه جداره کرده بود. در حالی که در ساخت یک خانهی غیرفعال ایدهآل باید از شیشهی کمتری استفاده شود، “خانه ما نسبت به طبقهی همکف و پوش شیشهی بسیار زیادی داشت که تنها دلیلش علاقهی ما به استفاده از آن بود.”

نتیجه یک سازهی زیبا و مدرن در منطقهی محلی ایل-دو-فرانس (Île-de-France) و یک نمونهی آزمایشی است. کارانشوا میگوید: «این پروژه در عمل نشان میدهد که هزینهها میتواند از ساختوساز معمولی ارزانتر باشد.»

Location Bessancourt, France (Seine River watershed)

Gross area 1,905 ft2 (177 m2)

Cost $377,900

Completed September 2009

Annual purchased energy use (based on simulation)

10 kBtu/ft2 (110 MJ/m2)

Annual carbon footprint (predicted)

.1 lbs. CO2/ft2 (,5 kg CO2/m2)

Program Bedroom, kitchen, bathroom, living room, and garage

>TEAM

Owner, architects, and interior designers

Karawitz Architecture

Engineers Solares Bauen (thermo); DI Eisenhauer et Philippe Buchet (structural)

>SOURCES

Structural system Finnforest Leno/Merk

Insulated panel/plastic Menuiseries Andre Optiwin

Photovoltaics Systaic

Waterproof membrane SIKA Sarnafil

Insulation ISOFLOC, cellulose

Heat recovery ventilation Genvex Combi185

Rain-proof membrane Ferrari Architecture Stamisol

RIGHT The living spaces face the south in order to take advantage of the daylight- the house has no heating system.

LEFT Karowitz Architecture’s bamboo- dad Passive House stands out in its neighborhood, where 12th- and 13th-century architecture is the norm.

Passive Progressive

A bamboo-clad passive house outside of Paris breaks free from local tradition.

Architects Milena Karanesheva and Mischa Witzmann’s bamboo- clad passive house in Bessancourt, France, 20 miles northwest of Paris, has lured architectural tourists, locals, film crews, and friends of friends. They’ve come around to marvel at its presence in a town where 12th- and 13th-century structures along dense, narrow streets and courtyards trump modern design. As improbable as the house is, located between a historic district and small residences from the ’70s and ’80s, and as challenging as it was to build, it has helped promote the passive house ethos in a country that has been slower than others in Europe to adopt it.

When it was completed in 2009, the officially named Passive House was the second in France and the first in the Paris region. Since then, Karanesheva and Witzmann, wife and husband who founded their Paris-based firm Karawitz Architecture in 2005, have designed about seven passive houses. All except for two are in various stages of construction and completion. And in February, Karawitz was seeking a building permit for a coop apartment building in Paris that will use the passive house tenets.

The 1,900-square-foot, two-story bamboo Passive House is technically and programmatically straightforward, in large part because of strict local regulations and old civil codes, explains Karanesheva. They required a sloped roof and limited windows for intimacy and privacy. “We are modern architects we are not from the 18th century. For us it was very important to make it contemporary,” says Karanesheva. She and Witzmann accomplished that by abstracting the traditional form.

A nearly 2-foot-wide “spine” splits the simple rectangle in two. The south-facing section of the house, where most of the openings are, is twice the size of the north-facing section. The kitchen and living room face the south on the ground floor, three bedrooms and a play area face the south on the second floor. Bathrooms and a laundry room face the north. The spine opens at two points, serves as load-bearing support, and hides mechanicals. A metal lattice walkway on the southern facade of the second floor doubles as a balcony and supports window shutters.

After contemplating dozens of types of wood cladding, Karanesheva and Witzmann chose bamboo for its airy quality and irregularity. “As the house was compact, it was important that the skin be very light, that you could look through it,” remarks Karanesheva. In Europe, there are few projects using bamboo, and cladding a home with the hollow stems gave it a more noble purpose. It was also less expensive than wood.

The relative simplicity of the house, however, belies the bureaucratic and technical struggles the architects endured to realize it. Karanesheva, who is Bulgarian, and Witzmann, who is Austrian and German, were familiar with the passive house concepts. The performance certification has roots in homes built across North America in the 1970s during the oil crisis, and was formalized in Germany in 1996, when Dr. Wolfgang Feist (see Feist’s Physics, p. 21 in the January/February 2011 issue) founded the PassivHaus Institut. But when the architects searched for a client to finance their prototype in France, they were met with doubts about its functionality and sometimes laughter.

“It was hopeless,” says Karanesheva. At the same time, their family needs were changing and they decided to build the house for themselves.

The site was an important factor- Karanesheva didn’t want to rely on a car, so the house had to be near the local rail station and amenities. A well-oriented spot just behind a church from the 12th century was perfect, but a local decision-making body in charge of protecting monuments initially resisted Karawitz’s design. Bamboo? Photovoltaics? Absolutely not. After many exchanges, the group’s skepticism turned into support, but not without some setbacks along the way. (Now even the local mayor is a fan.)

Simultaneously, Karanesheva and Witzmann had to find carpenters who could conform to the precise air tightness specifications necessary for passive houses a rarity in France, where most builders are masons. With a carpenter from Brittany and a Paris-based firm specializing in sustainable construction in place, the project became a success.

“We thought, ‘Well, a house without heating could be a problem,” says Karanesheva, but “I was surprised how comfortable it is.” When it’s sunny, the temperature in the house rises quickly, with only 0.48 air changes per hour and a heat recovery rate of 76 percent. The architects were in luck when it came to the triple- glazed windows as a local firm had just begun to supply them. While the ideal passive house should have less glazing, “our house has quite a lot of glazing proportional to the ground floor and envelope, but that’s because we like it,” comments Karanesheva.

The result is an elegant, modern take-off on the local barns of the Ile-de-France region, and a prototype against the odds. “It shows that it is possible, that costs are not higher than normal construction costs, and that it works,” says Karanesheva.