مسکن اجتماعی، اینترلیس (Interlace) سنگاپور برترین ساختمان جهان در سال 2015 اثری از اولی شیرن و دفتر معماری متروپولیتن (Office for Metropolitan Architecture)، ترجمهی الناز شمالی

WORLD BUILDING OF THE YEAR THE INTERLACE, SINGAPORE OMA/OLE SCHEEREN, Ts Elnaz Shomali

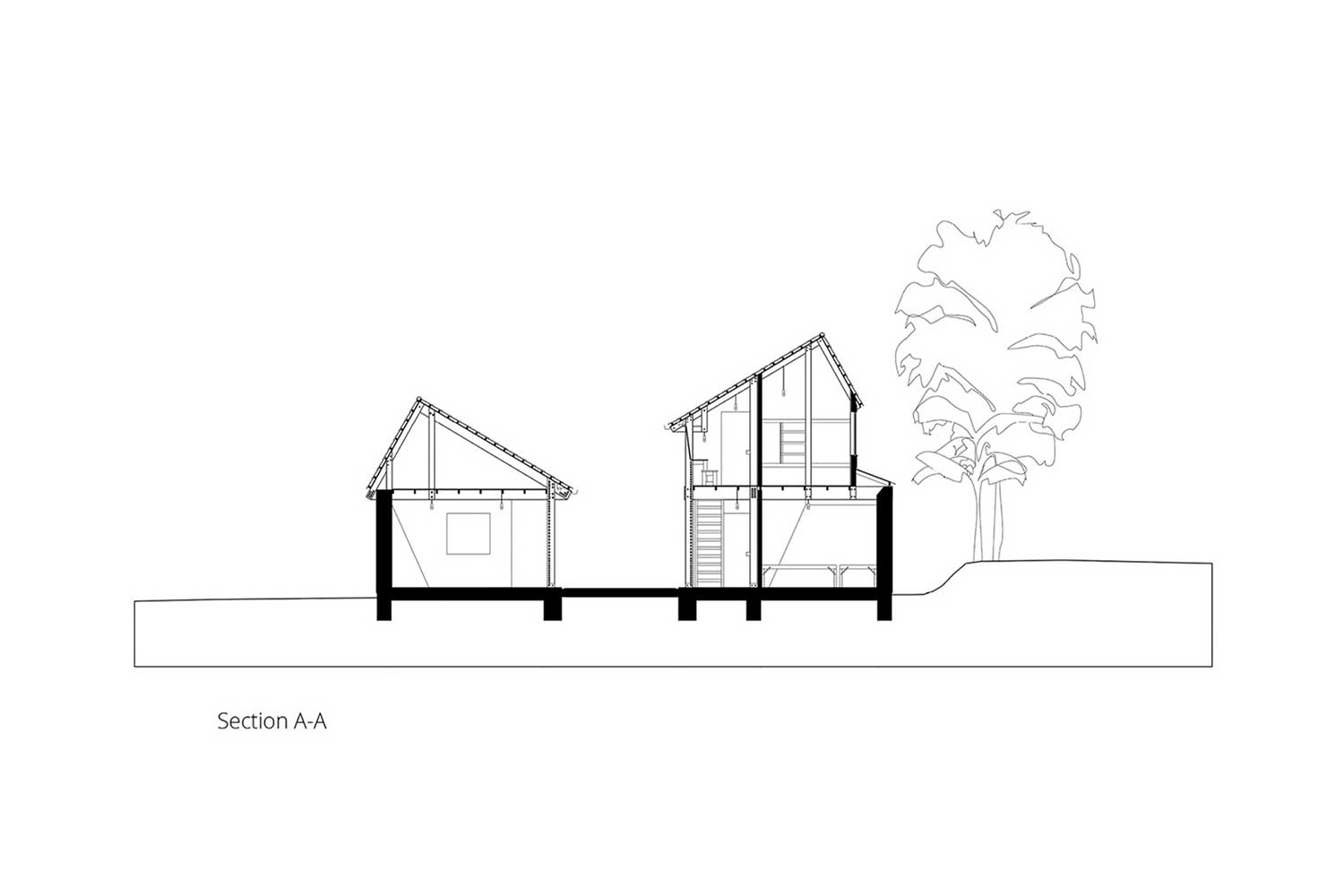

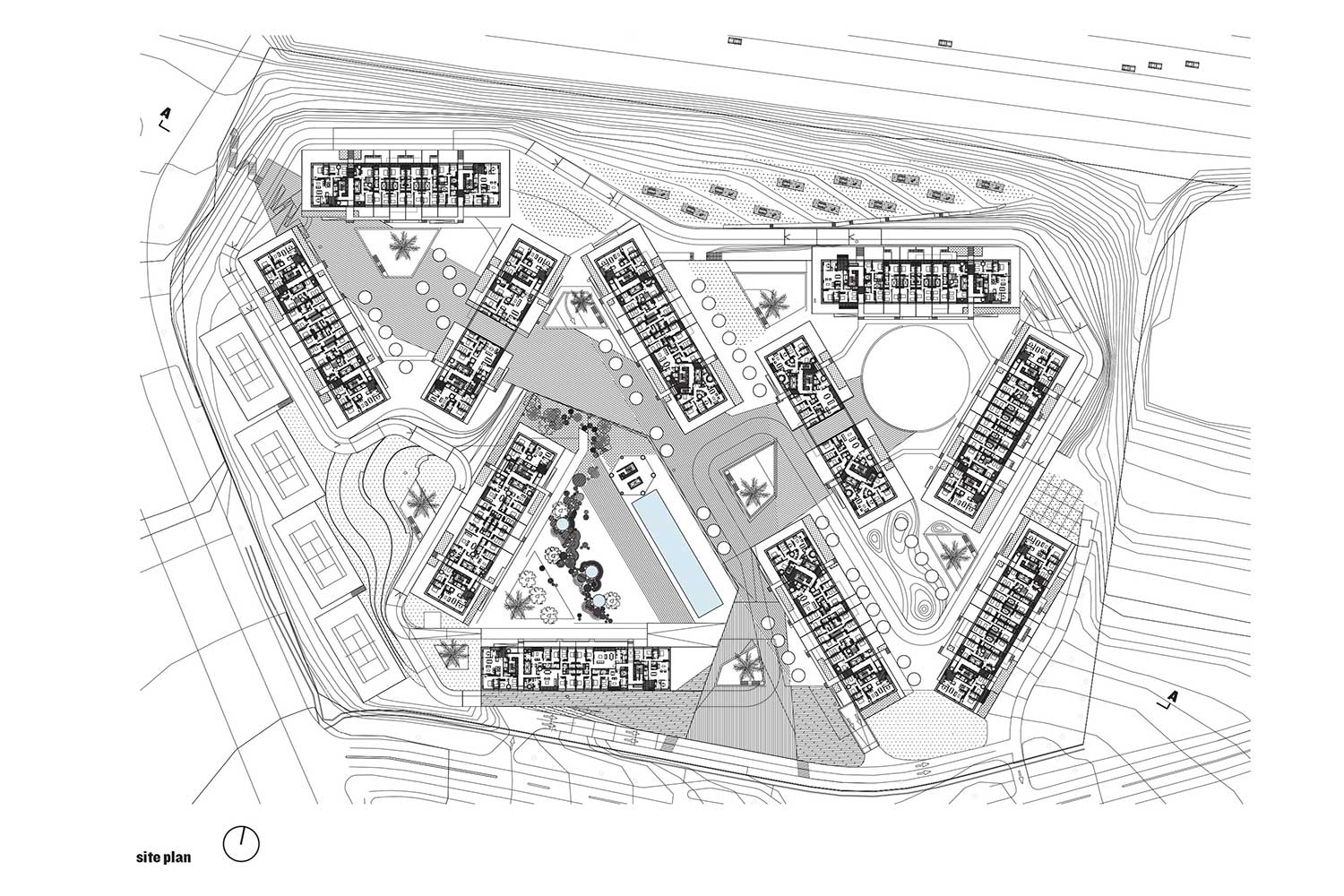

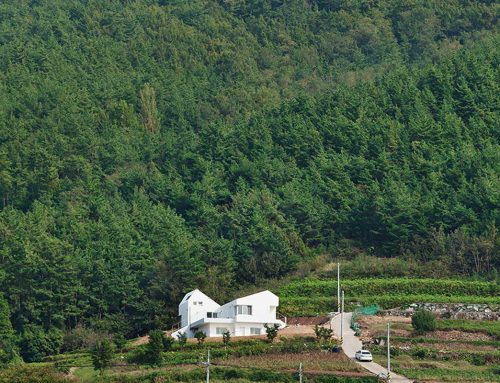

مجتمع مسکونی اینترلیس که از نظر لغوی به معنای در هم تنیده است در سنگاپور واقع شده و در سال 2015 به عنوان ساختمان سال هشتمین جشنواره جهانی معماری شناخته شد. این مجتمع توسط معمار آلمانی اولی شیرن با همکاری دفتر معماری متروپولیتن طراحی شد. پروژه اینترلیس مجموعهای عظیم از چند آسمان خراش است که شامل خانههایی برای اقشار کم درآمد میباشد. ایدهی اولیهی طراحی این مجموعه برگرفته از بازی جنگا میباشد.

اولی شیرن متولد سال 1971 در آلمان است. او تحصیلات معماری خود را در مؤسسه فناوری کارلسروهه (Karlsruhe Institute of Technology) و مؤسسه پلیتکنیک فدرال (École Polytechnique Fédérale) گذراند و در مدرسهی معماری انجمن معماری (Architectural Association School of Architecture) از رسالهی خود دفاع کرد. او از سنین کم در دفتر معماری پدرش مشغول به کار شد.

دفتر معماری متروپولیتن با شعباتی در روتردام، نیویورک، هنگکنک، دوحه و استرالیا در حال فعالیت است. این شرکت معماری توسط هشت شریک اداره میشود و از شکل سنتی معماری و شهرسازی دنبالهروی میکند. این شرکت تحقیقاتی و طراحی، تفکر معماری را ارتقا میدهد و در حال حاضر مشغول ساخت پروژههای گوناگونی در سراسر جهان است.

در نسخهی آوریل 2015 مجلهی The Architectural Review، روآن مور (Rowan Moore)، منتقد حوزهی معماری ساکن لندن، گزارش خود و پیشبینیاش دربارهی مجتمع مسکونی اینترلیس را منتشر کرد. این مجتمع مسکونی 24 طبقه با مساحت 170000 مترمربع حساسیتهای اروپا را بر هم خواهد زد. در حالی که طراحی 31 بلوک مسکونی در شش طبقه بیمعنا به نظر میرسد و به شکل دستهی پراکندهای از آجر بازی کودکان است از دیدگاه عدهای چندان هم معصومانه نیست. او نوشت: «این ابرساختمان مسکونی بتنی به سبک دههی 60 مدتها بدترین کابوس شهری تلقی میشد، ممکن نیست دوباره به چنین چیزی برگردیم.»

اما در نهایت چنین نتیجه گرفت که اگرچه در نگاه نخست این سازه عجیب به نظر میرسد اما تجربهی متفاوتی را القا میکند. این سازه جسارت و ذکاوت را به گونهای تلفیق میکند که در پروژههای مسکونی زیادی با آن مواجه نشدیم.

با چنین تمجیدی که مور از این پروژه داشت و آن را همرده با اونیته (Unité) لو کوربوزیه (Le Corbusier) و هلال سلطنتی (Royal Crescent) جان وود (John Wood) دانست دور از انتظار نبود که شش ماه بعد به عنوان برترین ساختمان سال هشتمین جشنواره جهانی معماری شناخته شد. با این حال، پیش از آنکه نظریهپردازان تئوری توطئه و خوانندگانی که متقاعد نشدهاند معترض شوند، باید درک کنند که انتخاب این مجموعه به عنوان برترین ساختمان سال چندان هم ساده نبود.

فرآیند داوری زندهی جشنواره جهانی معماری که از سال 2008 آغاز شد نقطهی عطف آن است. این رویداد سالانه عمداً ازحساسیتهای منطقهای، برداشتهای اولیه و شباهتهای سطحی فراتر میرود تا معماری را به عنوان یک واقعیت جهانی در نظر بگیرد. نمایشگاه این جشنواره که شامل دو مؤلفهی اصلی است از همهی افراد حاضر بدون هیچگونه تبعیضی در مورد چگونگی پروژهها نظرسنجی میکند. پس از حضور معماران و ارائهی ایدههایشان و چگونگی محقق کردن آن داوری بین آثار آسانتر میشود و سپس برگزیدگان معرفی میشوند.

مراحل داوری این جشنواره با حضور همهی نمایندگان برگزار میشود تا شاهد بحث و گفتگو بین طراحان و منتقدان باشند فرآیندی که معمولاً در دیگر جوایز پشت درهای بسته اتفاق میافتد. مخاطبان این جشنواره که گاهاً تعدادشان به بیش از 700 نفر میرسد همگی شاهد فرآیند داوری هستند و در کنار آموختن نکات مفید از بهترین معماران جهان (هر فرد حدود 10 دقیقه فرصت دارد تا اثر خود را ارائه دهد) میتوانند با روند داوری و معیار داوران آشنا شوند. تفاوتهای زبانی و فرهنگی بر فرآیند داوری این جشنواره تاثیر نمیگذارد و داوران سلیقهای برخورد نمیکنند.

جلسات داوری این امکان را به هیئت داوران میدهد تا در هر دستهبندی (مسکونی، اداری، خرده فروشی و غیره) موارد مشابه را با یکدیگر مقایسه کنند و به طور خاص بر مسائل مربوط به بخشهای طراحی تمرکز کنند. همچنین نمایندگان در مورد هر اثر گفتگو میکنند که در رابطه با هر ساختمان مسالهای کلیدی محسوب میشود. این در نهایت هیجان و حدس و گمان در مورد نامزدها و برندگان در هر رده و همچنین انتخاب ساختمان سال را بالا میبرد.

انتخاب اینترلیس به عنوان برترین سازهی مسکونی جشنواره بسیار مورد بحث بود. ابتدا از میان 14 طرح از اروپا، آمریکای جنوبی، استرالیا، آسیا و اقیانوسیه در رده مسکونی برنده شد و سپس به عنوان برترین طرح به انتخاب داوران در همهی ردهها معرفی شد.

انتخاب برترین ساختمان سال از میان ساختمانهای مسکونی که از پرطرفدارترین انواع سازه ها هستند چالش محسوب میشود زیرا طرحها به ندرت از مدلهای پذیرفته شده و اثبات شده منحرف میشوند. در سراسر جهان بهترین سازههای مسکونی ساختمانهایی با طرح ساده و زیربنایی هستند. به همین دلیل مور بر این باور است که به ندرت تغییرات جسورانه یا هوشمندانه در طراحی این گونه از ساختمانها اتفاق میافتد.

به همین جهت هرساله در لیست برگزیدگان ساختمانهای مسکونی آثار شاخصی وجود دارد اما تفاوت چندانی با آثار سالهای ماقبل آن ندارد. اما برج مسکونی Sky Terrace @ Dawson اثر معماران SCDA و مجتمع مسکونی اینترلیس اثر اولی شیرن از سایر پروژههای ساختمان سال متمایز بودند.

هر دو سازه طرح جدید و بلندپروازانهای دارد. اولی 758 واحد مسکونی در پنج برج 40 تا 43 طبقه و دومی 1040 واحد و ارتفاعی نصف اولی دارد. بر خلاف دیگر آثار، هر دو طرح واقعاً نوآورانه و جاهطلبانه بودند و بیشتر با یکدیگر مقایسه میشدند زیرا هر دو در شهر میزبان جشنواره یعنی سنگاپور قرار داشتند. بنابراین باید اعتراف کرد که تصمیمگیری نهایی بسیار دشوار بود. با این حال، در نهایت، وضوح و جاهطلبی اینترلیس نظر داوران را جلب کرد و با نتیجهگیری مور موافق بودند که این سطح از جسارت و هوشمندی به ندرت در بخش ساختمانهای مسکونی دیده میشود. در نهایت اینترلیس به بخش انتخاب بهترین اثر توسط هیات داوران وارد شد. داوران بیشتر به دنبال انتخاب اثری بودند که لذت حقیقی هنر معماری را به تصویر میکشید. . هیئت داوران باید ساختمانهایی را با مقیاسها، اهداف و بودجههای کاملاً متفاوت با هم مقایسه کنند. معیار اصلی انتخاب یک اثر میزان تاثیرگذاری آن است اینکه تا چه اندازه فکر و احساس بیننده را درگیر میکند. اگرچه این جایزه همیشه باعث اختلاف نظرهای بسیاری بوده، اما میتوان قاطعانه گفت که هفت برندهی قبلی همگی نشان دادند که چگونه معماری میتواند زندگی افراد، جوامع و ملتها را در سراسر جهان تغییر دهد.

در لیست منتخبان این جایزه، اینترلیس نظر تعداد بیشماری از افراد را به خود جلب کرد و همگی مشتاق شنیدن نظرات هیات داوران بودند. طبق سنت هرساله، هیئت داوران اثر منتخب را نه تنها بر اساس تخصص طراح، بلکه بر اساس توانایی او در بررسی هر طرح، طرح سوالات مرتبط، گسترده و فراگیر انتخاب میکنند. پیتر کوک (Peter Cook) یکی از داوران معتقد بود همهی معماران باید تعصبات را کنار بگذارند و از چهارچوبها خارج شوند و از استفاده از مصالح تکراری در طرحهای خود بپرهیزند. میشل روکیند (Michel Rojkind) اظهار داشت که معماران با این طرح میتوانند نظر مشتری را تغییر دهند. آلن بالفور(Alan Balfour) معتقد بود باید این سوال را مطرح کنیم که آیا شواهدی در این سازه هست که نشان دهد معماری چگونه جوامع را شکل داده است؟

این سازه همانند دیگر سازههای بزرگ جهان کاستیهایی هم دارد اما قطعا انتخاب درستی به عنوان برترین ساختمان جهان بود. یکی از اعضای هیات داوران پس از جشنواره به این مجتمع مسکونی مراجعه کرد تا مطمئن شود آیا اینترلیس بهترین انتخاب بوده و یک خانوادهی سه نفره تایید کردند که چقدر از زندگی در چنین مجموعهای راضی هستند و قطعاً باارزشترین جایزه رضایتمندی ساکنان این مجموعه است.

In the April 2015 edition of The Architectural Review, London-based critic Rowan Moore introduced his report on Interlace with a prediction. Ole Scheeren and OMA’s 170,000 m2, 24-storey private housing scheme would unsettle European sensibilities. While describing the arrangement of 31 six-storey residential blocks as nonchalant, likening its figure to a stack of children’s bricks, he suggested that for some it would hold less innocent associations. ‘Here is,’ he wrote, ‘something that looks like the very thing long considered the worst urbanistic nightmare, the cause of the mea culpa of a generation of chastened architects – a ’60s-style concrete housing megastructure … The Thing To Which We Would Never Return?’

As his account of the “Tropical Megalith’ developed, however, the acclaimed author of Why We Build suggested that ‘for all its resemblance to architectural types commonly considered alienating, this is not the experience it offers’, concluding that it ‘combines boldness and intelligence in a way rarely seen in housing projects’.

With such high praise, it was unsurprising that six months later the building that Moore credited with the magnificence of Le Corbusier’s Unité or John Wood’s Royal Crescent was crowned as the 8th World Architecture Festival’s World Building of the Year. However, before conspiracy theorists and unconvinced readers cry foul, it should be understood that this decision was in no way inevitable, nor easily reached.

Since launching in 2008 the format of its live judging process has become the World Architecture Festival’s unique selling point. The annual event deliberately looks beyond regional sensibilities, first impressions and superficial resemblance in order to consider architecture as a truly global act. Comprising two main components, the festival exhibition presents an unfiltered

all-comers’ survey of the good, the bad and the ugly. Within this context, the judging process brings an essential layer of rigour, through a shortlisting and crit session format that makes global comparison more meaningful by focusing on the ideas and processes behind the realisation of each building, as much as on their completed form.

In this pursuit, conversation is king at WAF, with all delegates invited to witness discussions between designers and critics that in other awards programmes would typically take place behind closed doors or on privileged site tours. With audiences of up to 700, everyone sees the evidence, not only providing a master class in clear-thinking presentation by some of the world’s best architects (who have to describe their work in 10 minutes), but also in the formation of critical observation by the panels of international judges who quiz them on key issues. Language barriers and cultural differences demand clearly articulated arguments from both sides, leaving no place for skirting around the issues or being distracted by notions of taste. First judged in categories, (housing, office, retail and so on) the crit sessions not only allow the juries to compare like with like and to focus on issues relating to specific design sectors, they also provoke conversation and debate among the delegates as to what they consider to be the key issues in relation to each building type. This ultimately fuels excitement and speculation about category winners and the emerging front-runners for the more nuanced decision about which would or should become World Building of the Year.

For Interlace, the journey to become the festival’s first- ever residential winner was highly contested. Firstly it had to win the residential category from a shortlist of 14 schemes from Europe, South America, Australia, and Asia Pacific, before being considered alongside 16 other category winners in the Super Jury.

As one of the most demanding building types, housing often struggles to find its place in open award schemes, as the sort of market-led developments that dominate the sector rarely deviate from accepted and proven models. Across the world it is widely accepted that the best housing occupies the sort of good ordinary or background buildings that give places their essential, subtle or underlying character. This is why, as Moore suggests, it is rare for magnificent, bold or intelligent step changes to make an impact on this typology.

The result is that residential shortlists are often made up of brilliant but otherwise undistinguished versions of what we already have; and last year’s shortlist was no different. There were, however, two exceptions, that architect Johannes Baar- Baarenfels from Austria, past president of RIBA, Paul Hyett, and myself (as chair of the residential category jury) found hard to separate: the Housing and Development Board’s (HDB’s) publicly commissioned, Sky Terrace @ Dawson, by SCDA Architects; and Ole Scheeren and OMA’s Interlace, for private developer CapitaLand.

As detailed in our citation, both schemes provided ambitious new housing models, with the former providing 758 dwelling units in five 40 to 43-storey towers, and the latter 1,040 units in approximately half that height. Unlike the majority of entries, both schemes were genuinely innovative and ambitious, and comparisons between the two were made even more tense as both were located within the festival’s host city, Singapore. As such, there is no weakness in admitting that we struggled to come to a final decision and were very nearly persuaded by HDB’s enlightened social agenda and innovation in publicly funded multigenerational living. However, in the end, our decision was based on the clarity and ambition of Interlace, agreeing with Moore’s observation that this level of bold intelligence is rarely applied to the housing sector.

With this decision made, Interlace went on to face the Super Jury, where the conversation deliberately focused less on each project’s contribution to its respective typology and more on what could be grossly oversimplified as pure architectural delight. In this forum the jury has to compare buildings of radically different scales, purposes and budgets, and as such past winners have all had that which Álvaro Siza once described to me as ‘strong emotional impact’ – or that thing that reaches in and simultaneously grabs your head and your heart. While this award always divides opinion, there can be little dispute that the seven previous winners all demonstrate how architecture can move and change the lives of individuals, communities and nations all over the world; Grafton Architects’ powerful Università Luigi Bocconi, the beautifully crafted place of pilgrimage by Peter Rich Architects at Mapungubwe, Zaha Hadid’s dynamic MAXXI in Rome, Cloud 9’s mechanised Media-ICT building in Barcelona, Singapore’s own Cooled Conservatories by Wilkinson Eyre Architects, the highly mannered Auckland Art Gallery by Francis-Jones Morehen Thorp, and the tiny Vietnamese Chapel by a21 studio.

In its campaign to join this prestigious list, the Interlace presentation drew a capacity crowd of individuals keen to hear what the jury would say. As has become the WAF tradition, the Super Juries are selected not only on each individual’s expertise in the field, but also on their ability to drill into each scheme, to raise pertinent, broad, reaching questions and above all to avoid the trap of premature congratulation of individual schemes. This was certainly the case with this year’s collective, as they spared little time in raising key concerns.

Peter Cook kicked off the scrutiny, criticising the architects’ refusal to deviate and making a plea for them to be less dogmatic, and with opposition to the composition of repetitive components at the cost of making room for variance, expression, fun and identity. Michel Rojkind expressed his disappointment at the lack of accessibility across the site, stating that architects of this calibre should have been able to change the client’s mind. Alan Balfour joined in and completely derailed the architect and client’s suggestion that this was a vertical village, asking whether there was any evidence that the architecture had helped shape the community, before repeatedly asking: ‘But where is the school? Where is the school?’

So, was Interlace a worthy winner? In my view, yes; and I am glad we selected it as the category winner. But, as with all great buildings, it is not without its shortcomings. My own hope is that in time this striking new urban form will prove robust enough to allow the expressionless elevations and resort-like gardens to support additional layers of use and identity that better reflect the richness and vibrancy of the city that exists beyond its gates.

As a footnote to our judging experience, fellow juror Paul Hyett returned to the site after the festival to reflect on the decisions, and reported back that the young family of three who generously opened up their home to the jury proudly confirmed how delighted they are with their new home. And perhaps that is the greatest prize of all.