ویلای لواسان اثر گیسو حریری و مژگان حریری

لواسان، ایران، دفتر معماری حریری

اولین ساختمان سال ایران، 1395

Gisue Hariri, Mojgan Hariri / Lavasan Villa / Hariri & Hariri Office

ویلای لواسان

لواسان، ایران

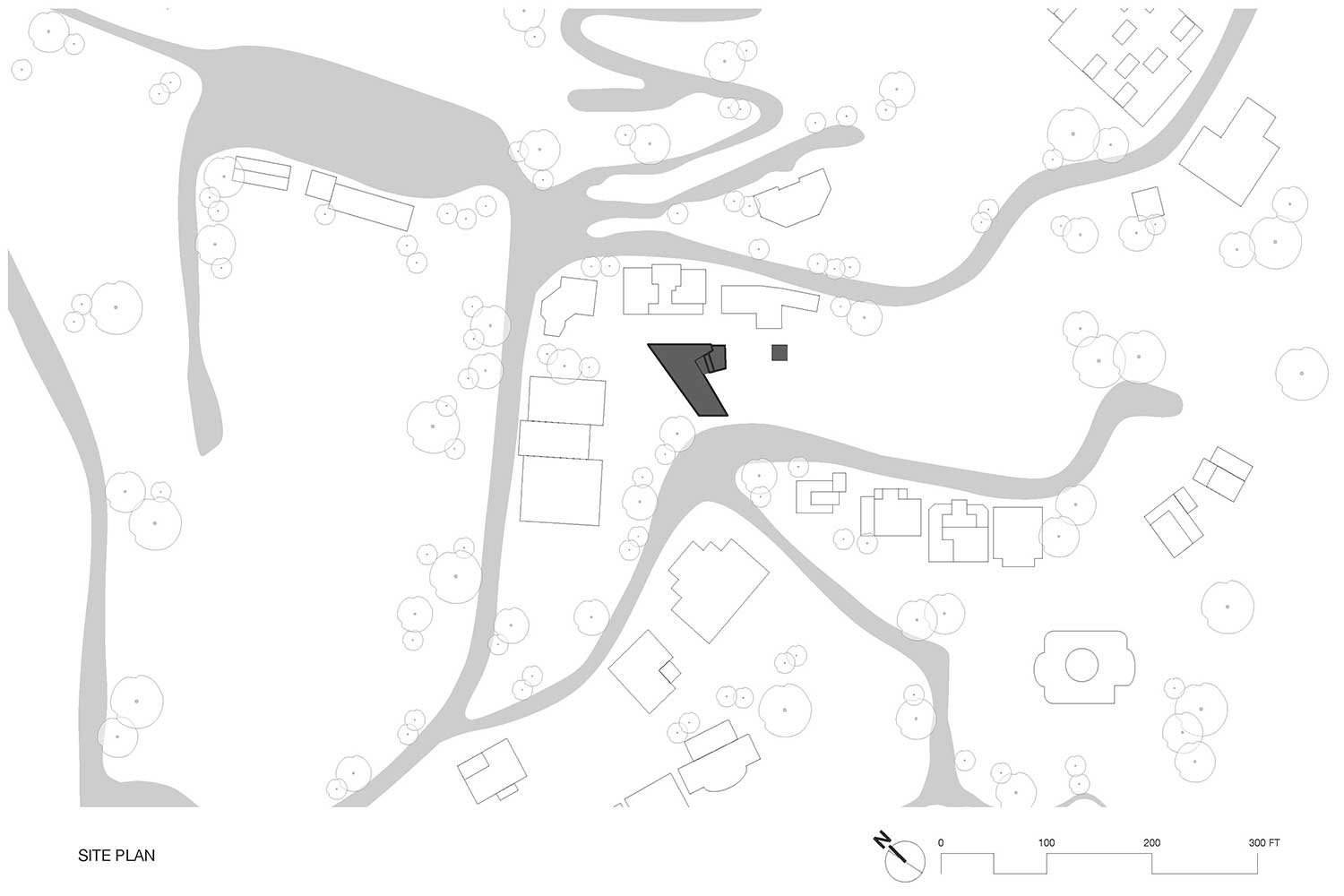

این ویلا بر روی زمینی با شیب تند در شهر مرفهنشین لواسان، واقع در ۳۰ دقیقهای مرکز تهران، قرار گرفته است. سایت پروژه مشرف به حوضه رودخانه جاجرود است؛ یکی از منابع اصلی تأمین آب منطقه کلانشهری تهران. این رودخانه در بخش جنوبی رشتهکوه البرز مرکزی جریان دارد. چشمانداز کوههای باشکوه البرز و رودخانه جاجرود، فضایی جادویی و خاطرهانگیز را برای این مکان رقم زده است.

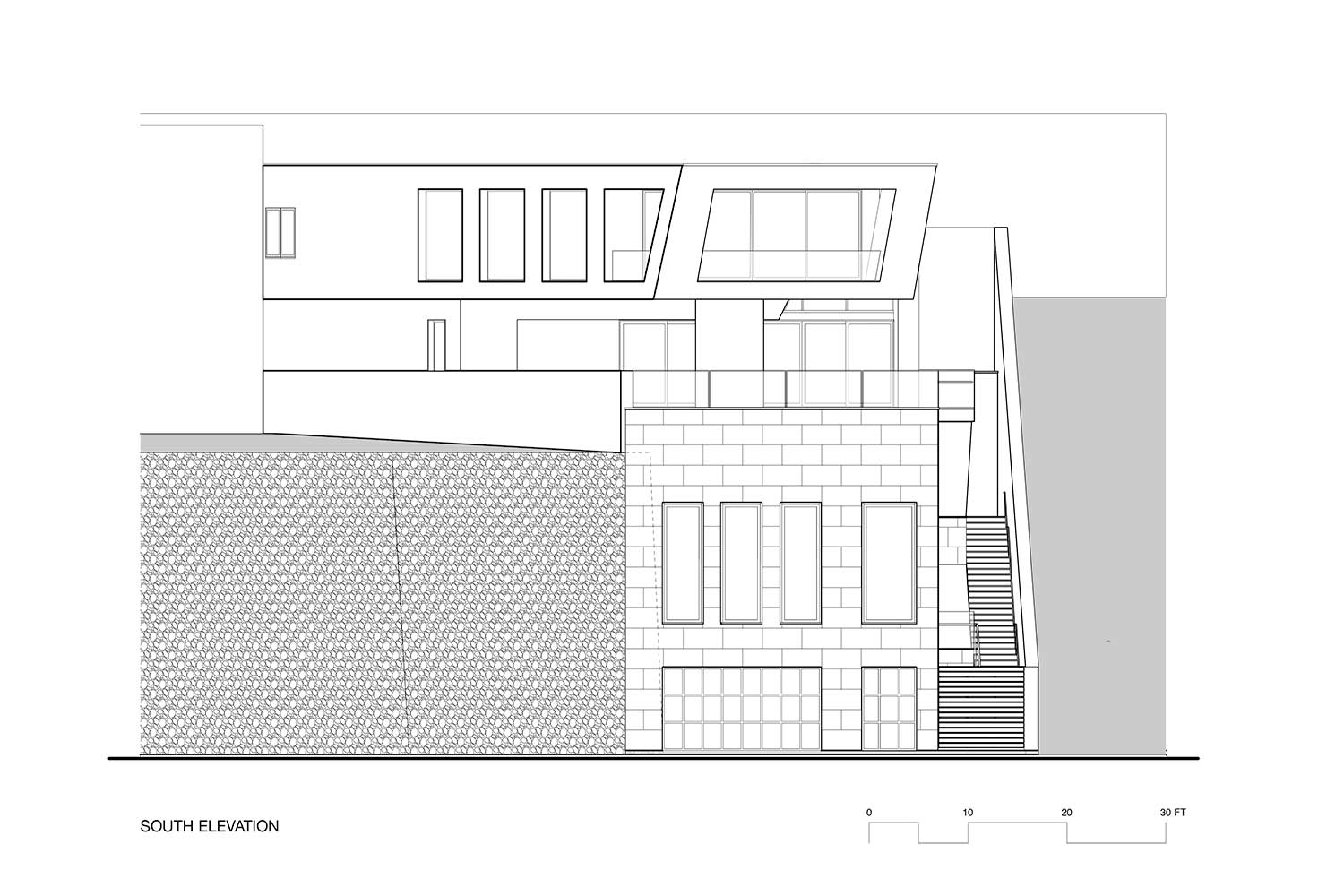

ورود به سایت از پایینترین بخش شیب تپه صورت میگیرد. دیوار سنگی به ارتفاع ۹ متر (۳۰ فوت) که متعلق به ویلای مجاور است، مرز یک سمت زمین را مشخص میکند. در بالای تپه و در فراتر از محدوده سایت، ردیفی از خانههای بزرگ پستمدرن و سنتی بهاصطلاح McMansion، بدون هیچگونه ملاحظهای در کنار یکدیگر صف کشیدهاند و در حجیمبودن، جلوهفروشی و جلبتوجه با یکدیگر رقابت میکنند.

چالش اصلی این پروژه، طراحی ویلایی ساده و همگون با توپوگرافی بود که ضمن پاسخ به خواست مالک برای تأمین حریم خصوصی (با توجه به سنت اسلامی مبنی بر دورماندن فضاهای خصوصی از دید عموم)، بتواند از مناظر پیرامونی بهرهبرداری حداکثری کند (یعنی امکان دید و لذتبردن از عناصر طبیعی دوردست و چشماندازها).

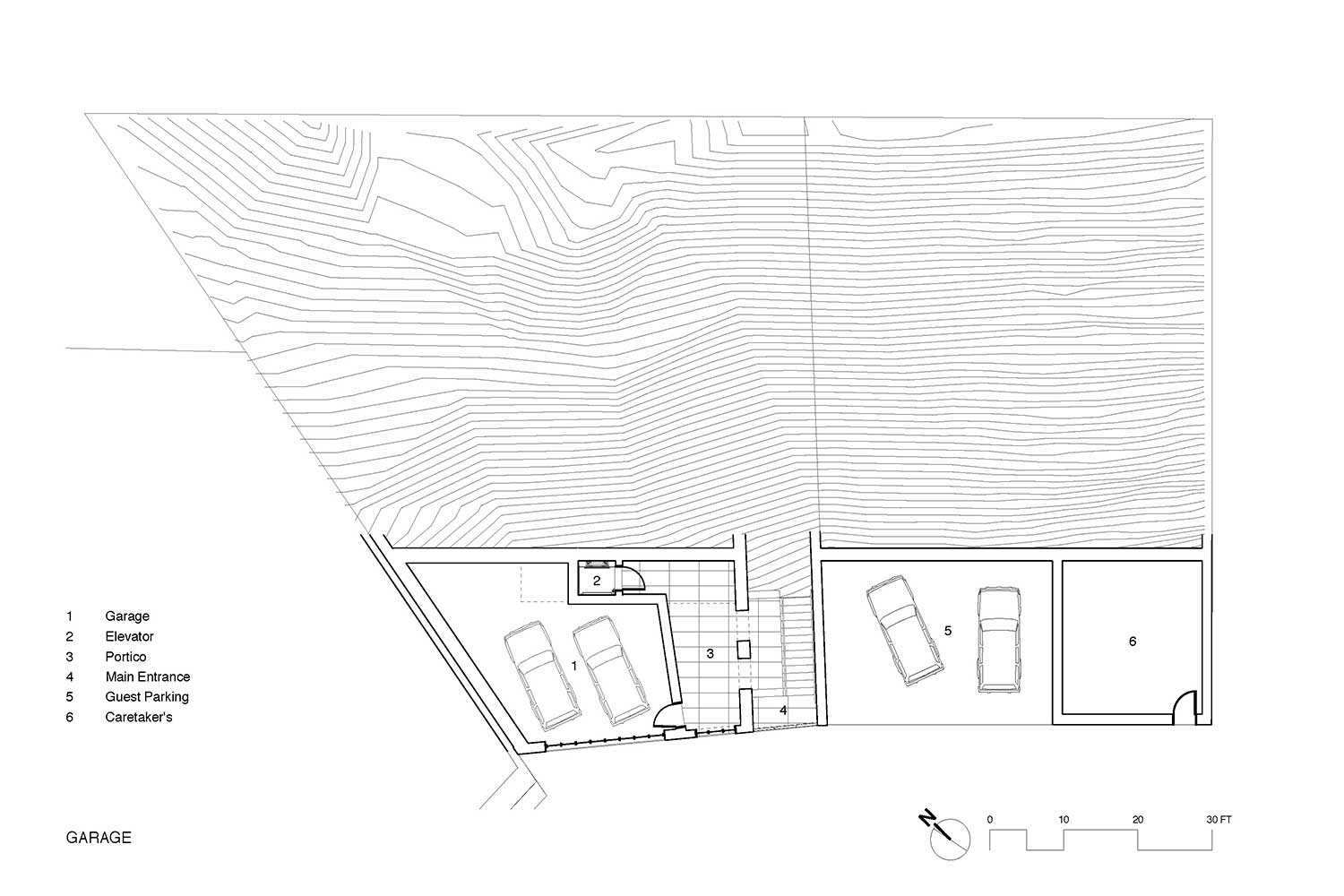

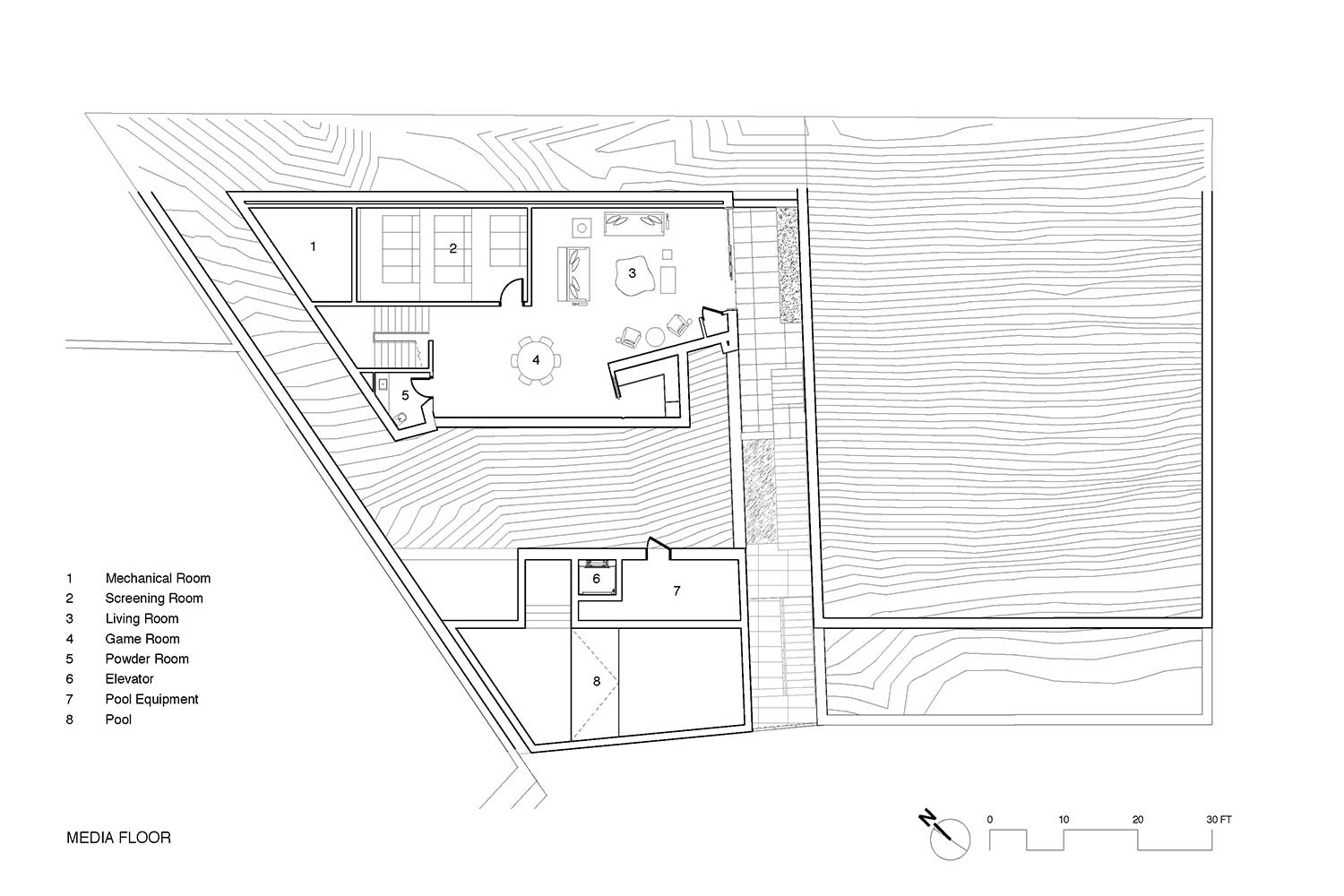

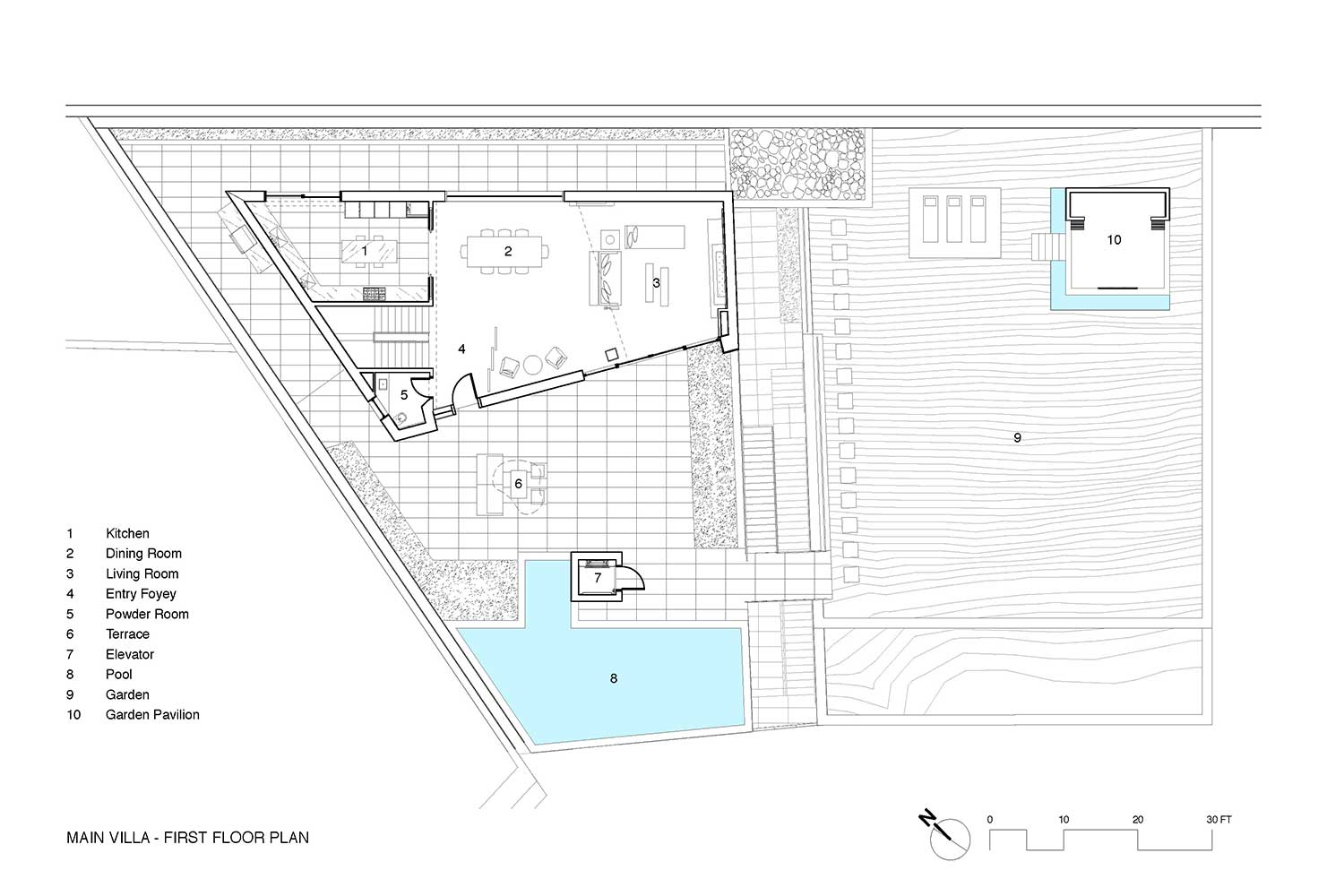

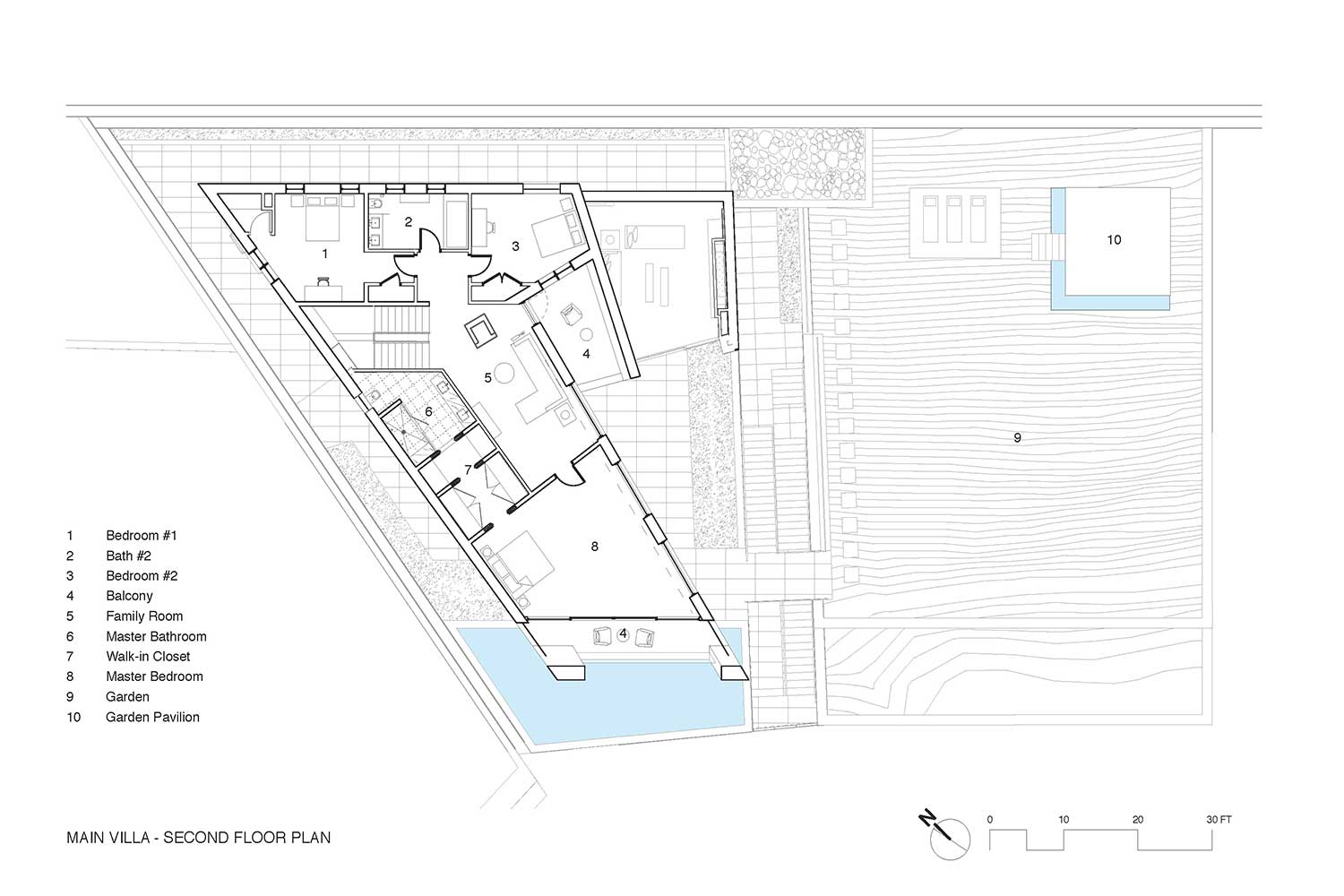

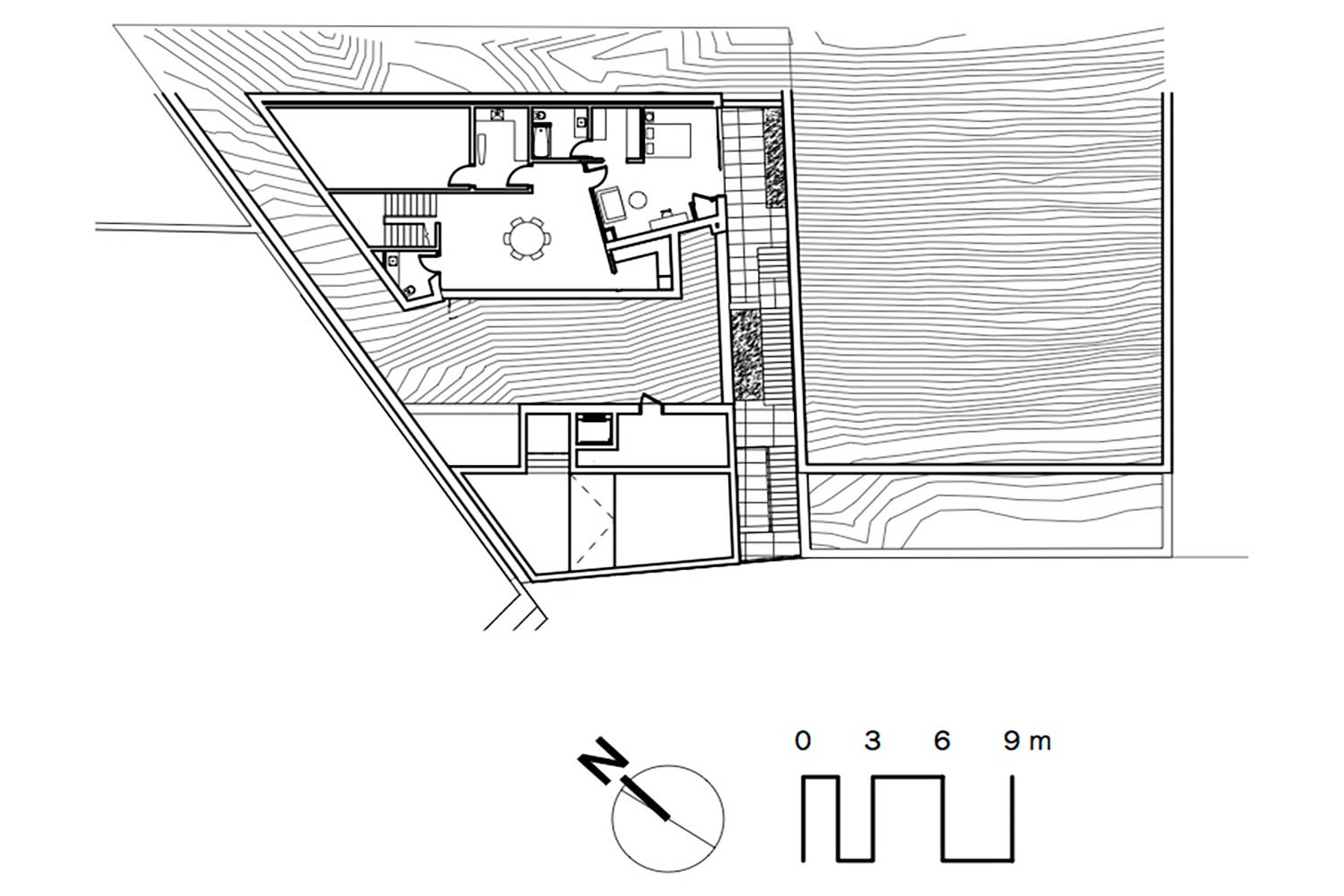

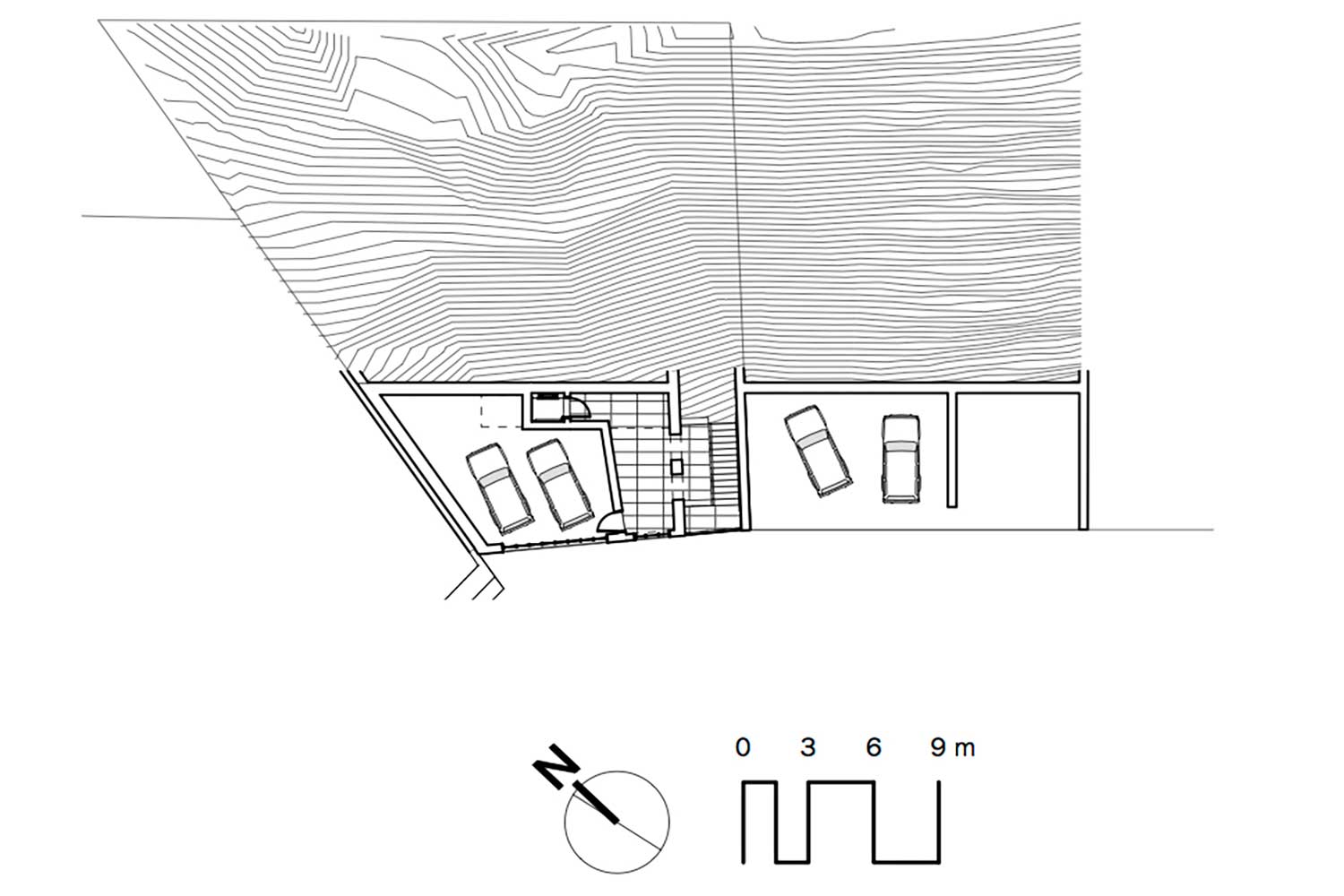

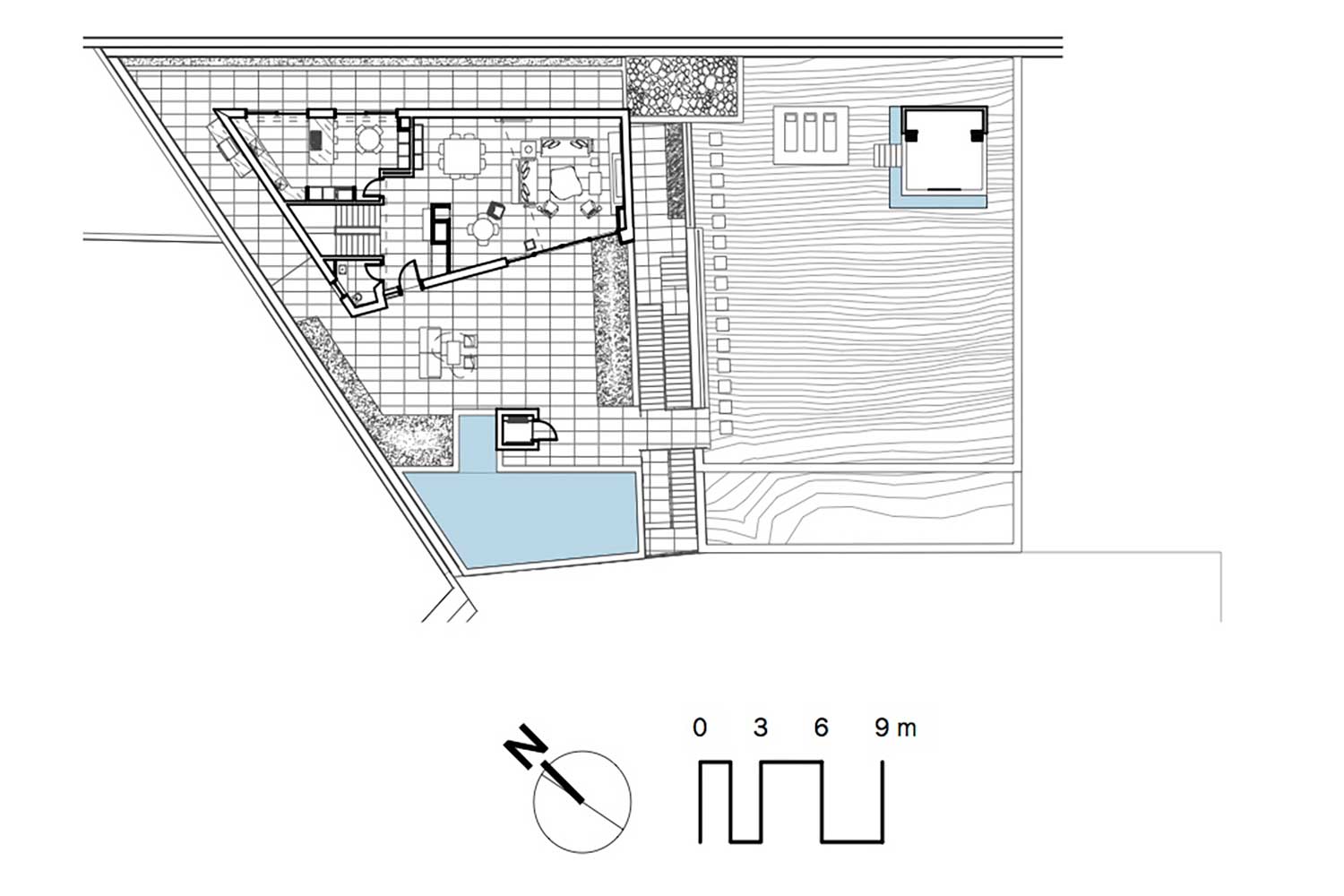

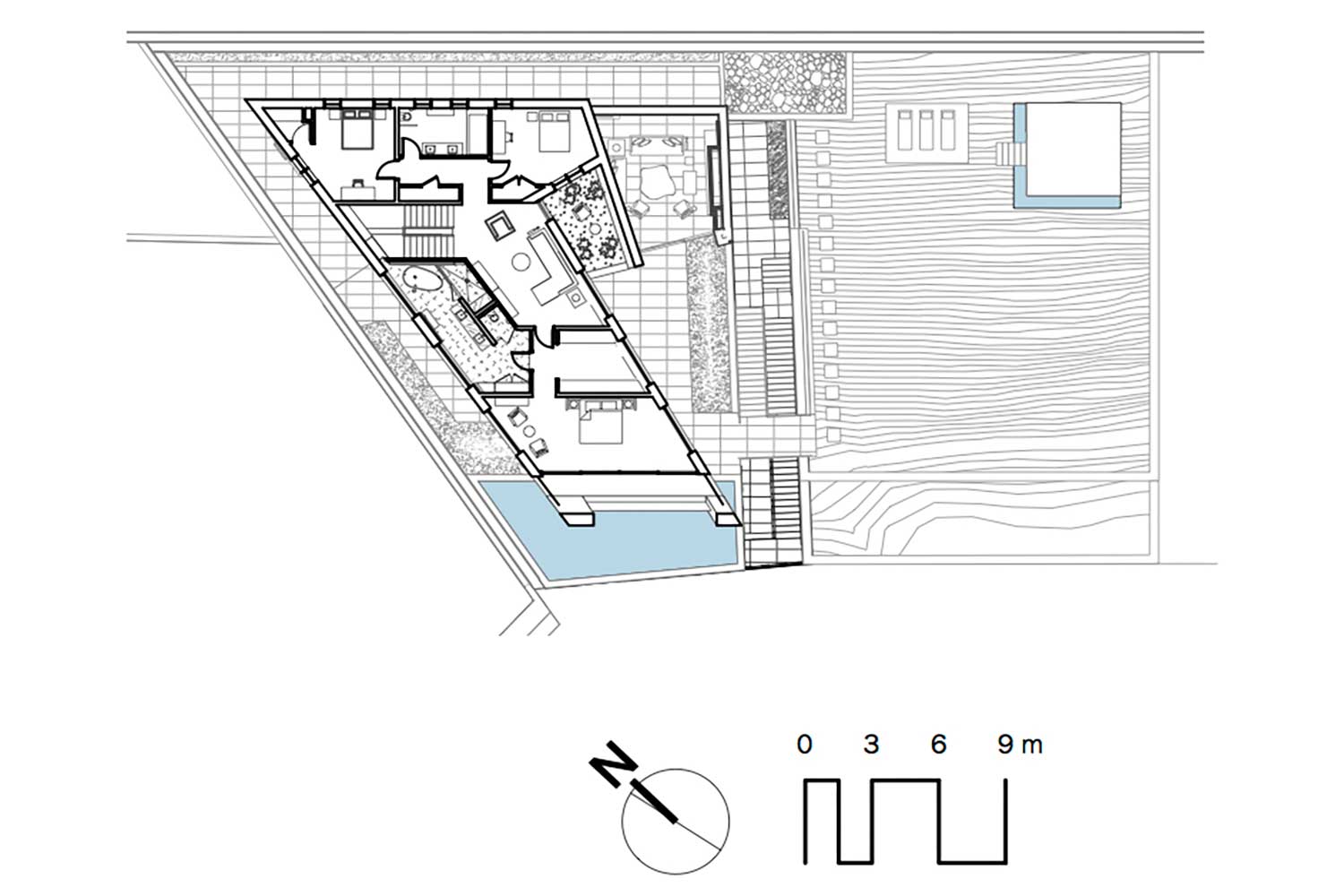

برنامهریزی فضایی پروژه شامل طراحی ویلای اصلی با کاربریهایی همچون: سوئیت اتاقخواب والدین، دو اتاق خواب فرزندان، سالن خانواده/تماشای تلویزیون، تراسها، نشیمن، فضای ناهارخوری، آشپزخانه، اتاق بازی، فضاهای باز و نیمهباز وسیع، و استخر شنا بود. افزون بر آن، یک مهمانسرای مستقل شامل یک اتاقخواب، نشیمن/ناهارخوری و آشپزخانه طراحی شد. همچنین خانه سرایدار، پارکینگ اصلی و فضای پارک اضافی برای ۴ تا ۶ خودرو مهمان در نظر گرفته شد. زمین همجوار نیز دارای یک فضای سبز/باغ و یک پاویون یا اتاقک چایخوری است.

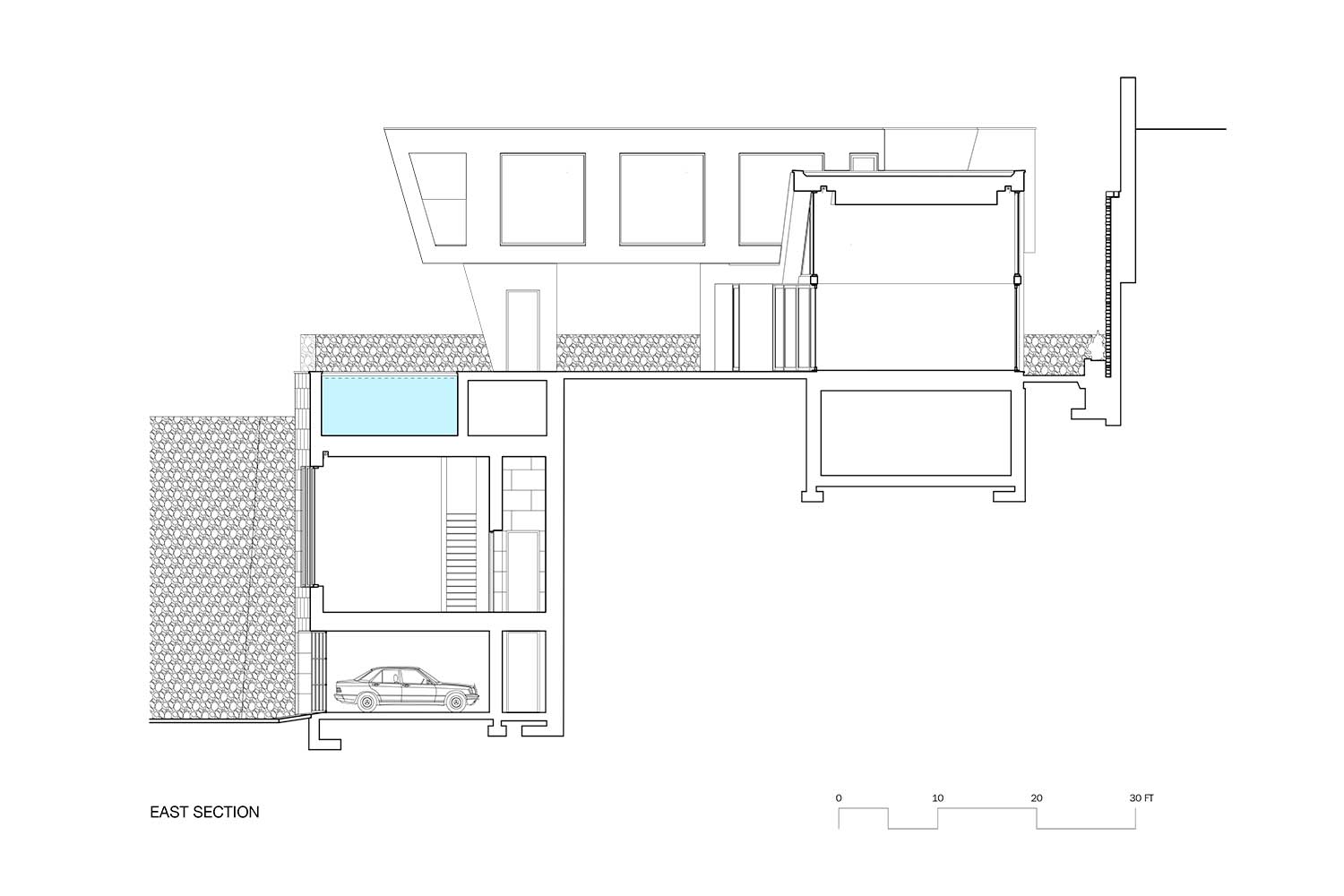

برای بهرهگیری حداکثری از مناظر کوه و رودخانه، فضاهای اصلی میبایست در ترازهای بالاتر سایت، حدود سه تا چهار طبقه بالاتر از محل ورود، جانمایی شوند؛ امری که نیازمند طراحی یک پلکان ظریف و آسانسور برای دسترسی به ترازهای مختلف بود.

از نظر مفهومی، ویلای اصلی به شکل یک حجم مجسمهگون بر فراز تپه شکل گرفت. احجام مربوط به مهمانسرا و خانه سرایدار به بخشهای کوچکتر تقسیم شده و در دل شیب تپه تراشیده شدند. ساختاری سهطبقه به عنوان پایهای برای ویلای اصلی عمل میکند و ادامهدهنده دیوار ۹ متری ویلای مجاور است. این حجم پایه شامل پارکینگ، ایوان ورودی، پلکان بیرونی، آسانسور و یک مهمانسرای دوبلکس است. بر روی بام مهمانسرا، سکویی برای استخر و ویلای اصلی قرار دارد که تنها بخشی از آن از خیابان قابل مشاهده است.

پلکان طویلی در سمت راست دروازه ورودی، مسیر دسترسی به بخشهای مختلف خانه را فراهم میکند. در مجاورت این پلکان، دیوار باغی قرار دارد که در کنار آن فضای پارک میهمان پیشبینی شده و در انتهای این بخش، سوئیت سرایدار جای گرفته است.

آسانسور، مسیر عمودی ارتباطی میان گاراژ و ویلای اصلی در تراز بالاتر را فراهم میکند و خروجی آن در کنار استخر قرار دارد. از نظر مفهومی، این عنصر عمودی مسیری را میپیماید که ساکن را از میان «زمین و آب» عبور میدهد تا به نقطه ورود برسد. ویلای اصلی به شکل حجمی L-شکل در دو طبقه طراحی شده که حیاطی خصوصی با پیوندی درونی-بیرونی را در بر میگیرد. این حیاط یادآور «ایوان» سنتی ایرانی است که به سوی باغ خصوصی گشوده شده و حوضی بازتابان در مرکز خود دارد. ورودی اصلی ویلا از طریق همین «ایوان» به یک فضای ورودی و سپس به نشیمن با سقف بلند و دیواری شیشهای منتهی میشود. فضای ناهارخوری باز، مشرف به باغ بامبو است و در جوار آشپزخانهای قرار دارد که بهواسطه درهای کشویی میتواند در صورت نیاز بهطور کامل بسته شود.

پلکانی با کفپلههای باز، ارتباط میان ترازهای مختلف را فراهم میآورد؛ به طبقه بالایی که محل اتاقهای خواب خصوصی است یا به طبقه پایینی که شامل اتاق بازی، سالن خانوادگی و سالن نمایش فیلم میشود. در تراز بالایی، دو اتاق خواب، یک نشیمن و یک تراس کوچک دید قرار دارد. در انتهای این حجم خطی و پلمانند در طبقه بالا، سوئیت اتاقخواب والدین با تراسی خصوصی معلق بر فراز استخر قرار گرفته است که چشماندازی پانورامیک به رودخانه و کوههای باشکوه پیرامون ارائه میکند.

از طریق پلی، ارتباطی به باغی با سطح چمن ایجاد شده است که برای بازی فوتبال یا لذتبردن از فضای باز بهکار میرود.

در نهایت، تجربه زیستن در بخشهای مختلف سایت و شیب تپه، بهویژه فضاهای «میانبر» میان احجام، پلکان طولانی و پیوند میان طبیعت و معماری، همان عاملی است که این ویلا را در ذهن ماندگار میسازد.

LAVASAN VILLA

Lavasan, Iran

This villa is located on a steep hilly property in the affluent town of Lavasan, only 30 minutes from Central Tehran, Iran. The site offers views of Jajrood River basin, one of the main sources of water for Tehran Metropolitan region. This river is located in the southern part of the central Alborz mountain range. The view of these majestic mountains and the Jajrood River makes this place magical and memorable. One arrives to the site at the bottom of the steep hill. A 30’ stone retaining wall of the next-door neighboring villa marks one side of the property line. On top of the Hill, above the property, are a series of postmodern and traditional McMansions lined-up shamelessly in a row next to one another competing in volume, vulgarity & visibility. The challenge of this project was to create a simple villa embedded in the topography that met the owners desire for privacy (Islamic tradition of not being seen by public in the private quarters,) while taking advantage of the surrounding views (seeing & enjoying the distant natural elements & views.). The program was to create a main villa including: a master bedroom suite, two children bedrooms, a family/TV hall, terraces, living, dining, kitchen, playroom, large outdoor/indoor space & a swimming pool. In addition to the main villa, an independent guesthouse was designed including: one bedroom, living/dining area, and kitchen. Also included are a caretaker’s house, garage, and additional parking spaces for 4-6 guests. The neighboring lot has a grassy field/garden and a pavilion/tea-room. In order to engage the views of the mountains & the river the main spaces needed to be on the higher elevations of the site some 3 or 4 stories above the arrival area which required an elegant staircase & an elevator to take one to different levels. Conceptually the main villa takes the form of a sculpture on top of the hill. The volume of the guesthouse & the caretaker’s house is broken down into different parts and carved into the hillside. A three-story structure creates a base for the main villa above continuing the next-door neighbor’s 30’ wall. This base volume includes the garage, entry veranda, exterior stair, an elevator and a duplex guesthouse. Above the guesthouse is a platform for the pool and main villa only partially visible from the street. A long stairwell on the right of the entrance gate takes one to different parts of the house. Next to the stairwell is a garden wall with a guest parking space and the Caretakers suite on the far end. The elevator takes one from the garage to the main villa above exiting by the poolside (conceptually this vertical element takes one thru the earth & water to get to the arrival point). The main villa is an L-shaped volume on two levels with a private indoor/outdoor court reminiscent of the traditional Persian IWAN facing the private garden with a reflective pool at the center. The main entrance to the Villa is from this “Iwan” to an entrance hall and a high ceiling living room with a wall of glass. An open dining area looks into a BAMBOO garden and is near kitchen with sliding doors allowing it to be completely closed if desired. A staircase with open risers takes one to the upper private area of the bedrooms or to the lower level where the game, family room & a screening room are located. Up above contains two bedrooms, a living room, and a small viewing terrace. At the end of the upper level rectilinear/bridge like volume, is the master bedroom suite with a private terrace hovering above the pool providing panoramic views of the River & the Majestic Mountains. Connected via a bridge is the GARDEN with grass surface for playing soccer and enjoying the outdoors. Finally it is the experience of occupying different parts of the site & the hill specially the spaces of IN-BETWEEN volumes, the long stairwell and bridging between nature & Architecture that makes this villa memorable.

شاید شفافترین پاسخ به پرسش مطرح شده در عنوان این باشد که چون «این ساختمان بلد است از خودش دفاع کند!». اما تمایل داریم پیش از اینکه داستان این جملهی کوتاه را برای شما بازگو کنیم، به بررسی نظری از ریچارد نویترا (1970-1892 میلادی) بپردازیم. ریچارد نویترا در کتاب خود تحت عنوان بقا به واسطهی طراحی (Survival Through Design) مینویسد:

«[…] خانه را میتوان مثل حقوق ماهانه طراحی کرد. در این حال، رضایت از طراحی ناشی از عادت (Habituation) است، اما شیوهی کاملاً متفاوتی نیز وجود دارد: طراحی برای حسی مثل دلهرهی عاشقانه، طراحی برای یک لحظه، برای کسری از یک ثانیه. [دیدهایم که] تجربهی تمام یک عمر میتواند در چند خاطره گرد آید. این بیشتر شبیه به شیوهی اخیر طراحی است: آمیختن با هیجان یک واقعه، در مقابل روند نخست که به امری ثابت و ملالآور میپردازد. ارزش یک در کشویی عریض که به یک باغچه باز میشود در همین است. […] در این دنیای پیچیده، طراح نباید فقط طبق اصول زیباییشناسی محض که ریشه در گمانهایی قدیمی دارد، عمل کند. […] چه از آن آگاه باشیم یا نباشیم، چه در محیطِ ایجاد شده خوشایندمان باشد یا آزارمان دهد، به هر صورت، صدای اتاق به عنوان یک پدیدهی صوتی پیچیده، حتی در اندک طنینهای خود نیز، بر ما مؤثر است.» (نویترا 1954، به نقل از مالگریو، 1395)

«این ساختمان بلد است از خودش دفاع کند» در واقع آخرین جمله ای بود که کارفرما و مالک ویلای لواسان، اثر خواهران حریری، در مکالمهی تلفنیمان به ما پاسخ داد. وقتی از او خواستیم که روز بازدید داوران جایزهی ساختمان سال، در محل حاضر باشد و تأکید کردیم که به دلیل عدم حضور معماران بنا در ایران ممکن است عمق اثر آنها برای داوران مشخص نشود و بهتر است معماران یا خود او برای بیان توضیحاتی هر طور که شده در محل حضور داشته بانشد، او پاسخ ما را تنها با یک جمله بیان کرد: «این ساختمان بلد است از خودش دفاع کند» و اینچنین بود که تیم نخست داوری پس از بازدید از این بنا، اصرار داشتند که حتماً تیم دوم داوران هم اثر را ببییند و به گزارشهای آنان و جلسهی نهایی اکتفا نشود. این بود که برای رعایت عدالت، آثار فینالیست، یا توسط کل تیم داوران در یک مرحله و یا هر یک دوبار بازدید شدند.

اما ماجرا چه بود؟ ظاهراً ویلای لواسان، اثر خواهران حریری، توانسته بود به راحتی از سد تمام معیارهای سخت و عمیق جایزهی ساختمان سال ایران گذر کند. این بنا، نه تنها با معیارهای داوری تطابق کامل داشت که پا را نیز فراتر گذاشته بود. ساختمان چیزی بیش از یک فرم کنسول شده در اراضی شیبدار لواسان بود و انفجارات پیاپی فضایی آن بیننده را تحت تأثیر قرار میداد. بنا قدم به وادی ارزشهایی گذاشته بود که در معماری ایران از آنها غافل هستیم یا فرصت توجه به آنها را نداریم. در ظاهر امر، دکوراسیون داخلی با هنرمندی خاصی چیدمان شده بودند و به خوبی قدرت همنشینی «معماری و دکوراسیون داخلی» را برای ما زنده میکرد؛ اصطلاحی که کم کم در حال پاک شدن از حافظهی معماریمان است. جالب آنکه سازهی بنا نیز علیرغم سختی کار، به خوبی پاسخگوی نیاز معماران شده بود؛ اصلی که ایدهآل است، اما گاهی برعکس میشود و معماری در خدمت سازه قرار میگیرد.

حالت فکری شما لطیف، سرد، زیبا و باشکوه بوده است. این را سنگهایی که به پا داشتهاید به من میگویند. شما نظر مرا به آن مکان جلب میکنید و چشمان من آن را مینگرند. آنها چیزی را میبینند که نمایشگر یک فکر است. فکری که نه با صدا یا کلام، بلکه تنها به وسیلهی اشکالی که در رابطهی معینی با یکدیگر قرار دارند آشکار میشود. این اشکال به گونهای هستند که در نور به وضوح نمایان میگردند. روابط بین آنها لزوماً ربطی به قابل استفاده یا در خور تشبیه بودن ندارد و آنها آفرینش ریاضی ذهن شما هستند؛ آنها زبان معماریاند. با استفاده از مصالح خام و شروع از شرایطی که کمابیش متکی بر سودمندی هستند، شما روابط معینی را به وجود آوردهاید که احساسات مرا برانگیخته است … این، یعنی معماری.» (لوکوربوزیه1923 ، به نقل از بلخاری، 1395)

به بیانی سادهتر، نویترا و کوربو به عنوان معمارانی مدرن، هر چند به فرمهای مکعبی سفید ماشینی مشهور شدهاند، اما دغدغهی فضای انسانی دارند. آنها قدرت معماری را درک کردهاند؛ قدرتی که از تلی خاک، فضایی خیالانگیز خلق مینماید. ایشان با نوشتن میکوشند مانیفست آثار خود را صادر کنند و بر لزوم وجود روح معماری در آثار معماری تأکید کنند. تأکید بر روانشناسی انسان و محیط و توجه به علوم عصبشناختی ــ با اینکه در زمان ایشان ما در گامهای نخستین علوم اعصاب بودیم ــ نشان میدهد که ما در مطالعهی تاریخ مدرنیته در معماری، از وجوهی غفلت کردهایم. جالب است که ریچارد نویترا در دههی چهل خورشیدی، به دعوت هوشنگ سیحون به ایران آمد. ورود او مصادف شد با باز شدن چشم معماران ایرانی به آثار مدرن، اما آنها نیز به خطا رفتند و مدرنیته را در مکعب سفید دیدند. کسی به روانشناسی و عصبشناختی حاکم در آثار نویترا دقت نکرد و ما در حالی با نویترا به واسطهی همایش و نمایش آثار آشنا شدیم که نمیدانستیم او مؤلف چندین جلد کتاب نیز هست. کتبی که وی در آنها بر لزوم توجه به علوم اعصاب در معماری تأکید میورزد. او در اوایل دههی 1950 خواستهای فراتر از زمانهی خود مطرح کرد و از طراحان خواست تا زیستشناس شوند؛ به این معنا که معمار، توجه خود را نه فقط به انتزاع فرمی، که باید بر گوشت و خون و نیازهای روانشناختی آنهایی تمرکز کند که در جهان مصنوع ساکن میشوند.

جدا از جمله ی مالک، طنز ماجرا آنجا است که خواهران حریری اثر خود را در شأن این جایزه در ایران نمیدانستند. زمینهای جنبی این ملک خالی هستند و ما وقتی به شیب وحشتناک این زمینها و برهوت آنها نگاه میکردیم، بیش از پیش به قدرت معماری در خلق فضای انسانی ایمان میآوردیم. تا حدودی میتوان علت افتادگی خواهران حریری پیرامون اثر خود را حدس زد. معماران این بنا در ایران نیستند و تصویری که از ایران داشتند، بسیار کارت پستالی که نه، اینترنتی بود! این روزها حتی بعضی از داخلیها نیز تحت تأثیر فضای مجازی هستند، چه برسد به کسانی که از آمریکا اخبار ایران را رصد میکنند و سالی چند روز در تهران هستند. خواهران حریری در برابر آثار داخلی، اثر خود را دارای قدرت رقابتی نمیدانستند، زیرا بعضی از تصاویری که از معماری ما مخابره میشود با چیزی که واقعاً هست متفاوت می باشد. اما کارفرمای آنان که در ایران حاضر می باشد و احتمالاً برای ساختن اثر خود به دفاتر بسیاری مراجعه کرده است، از قضیه با خبر بود. معماران و کارفرمای این بنا، حرف زیادی برای گفتن نداشتند و در چارچوب جایزه با نظمی حرفهای وارد شدند ــ علی رغم آنکه در کمال تعجب، برخی از معماران قانون بازدید حضوری از بنا را غیر ضروری میخواندند.

اما در این جایزه، «بودن» در معماری و درک آن از طریق حواس با نگاهی هدفمند و گزینشگر است که اهمیت می یابد. این ساختمان از معیارهای روز معماری در ایران فاصله گرفته و به کلاس جهانی نزدیک میگردد. یکی از بهترین وصفها میتواند معیارهای یوهانی پالاسما در وصف معماری خوب باشد که ماگریو به نقل از او در کتاب مغز معمار: علوم اعصاب، خلاقیت و معماری شرح میدهد. او در مقالهی شش مضمون برای هزارهی بعدی (1994) فهرستی از شش نکته برای احیای افسون معماری ارائه میدهد که عبارتند از آهستگی (Slowness)، انعطافپذیری، وابستگی به حواس (Sensuousness)، اعتبار (Authenticity)، دلخواهسازی (Idealization) و سکوت (Silence). در همین راستا پالاسما پیرامون معماری بر بساوش بصری اینگونه مینویسد: «معماری مبتنی بر چشم، تجزیه و کنترل می کند، در حالی که معماری مبتنی بر بساوش بصری، مجذوب و یکی می گرداند» (به نقل از مالگریو، 2010) و خود نیز در آثارش به عمق احساسات دل میبندد و نه فرم ظاهر، بنابراین باید قضاوت معماری نیز، با یاری و تمرکز تمامی حواس صورت پذیرد. ما معتقدیم، ویلای لواسان خواهران حریری، که به درستی به عنوان ساختمان سال ایران برگزیده شد، حامل پیام های متفاوتی از مناظر گوناگون است، اما بهترین آن، همان است که کارفرما پشت تلفن با اطمینان و رضایت کامل عنوان نمود: «این ساختمان بلد است از خودش دفاع کند!»

پیشنهادات ما با نگاهی به تجربهی جایزهی ساختمان سال ایران:

1. توجه به علوم روز جهان معماری، خصوصاً جریاناتی که سطحی و مدمآبانه نیستند و در لایههای عمیق معماری جهان نقش دارند.

2. گذر از فرمالیسم معماری، خصوصاً فرمالیسمی که منجر به حذف انسان، افزایش هزینهها، دوری از واقعیت معماری و آسیب به منافع فردی و ملی میگردد.

3. گذر از معماری پرحرف، اما کمارزش که میکوشد با حرفهای پراکنده و دور از اصل معماری، آن را توجیه کند.

4. گذر از تصویر سازی در معماری، خصوصاً آنجا که تلاش میشود با تبدیل فضای سهبعدی به عکس دوبعدی، آن را اصلاح نمود.

5. گذر از زیباییشناسی صوری که اغلب بر اساس الگوهای کهن شکل گرفتهاند. اصولی که فضای معاصر و آیندهبینی در آن جایی ندارد. از آنجا که خطکشهای زیباییشناسی بر اساس فرهنگ غربی متر شدهاند، ممکن است با روحیات ما حتی در تعرض باشند.

6. توجه بیشتری به دانشهای نوین فرامعماری در آموزش معماری و فرهنگسازی مبتنی بر معماری با علوم اعصاب شود.

7. ترویج طراحی معماری بر اساس معیارهای انسانمحور صورت پذیرد.

8. به معماری چند حسی توجه شود.

9. تلاش در جهت ترغیب مهندسان مشاور با تجربه و متبحر و دیگر بخشهای معماری که بیتوجه به جریانات معماری جهان، به طراحی و اجرای آثار دولتی مشغول هستند.

کتاب سال معماری معاصر ایران، 1398-1397

___________________________

عملکرد :مسکونی، ویلایی

________________________________

نام پروژه: ویلای لواسان

طراحی: گیسو حریری و مژگان حریری

کارفرما: رامین وارسته، رعنا وارسته

نظارت و اجرا: نوید قاسمی، پرویز کریمی

تاریخ شروع: بهار 1391

تاریخ پایان: بهار 1395

آدرس پروژه: لواسان، استلک بالا، خیابان شکوفه، خیابان نگار، پلاک 50

وب سایت: haririandhariri.com

اینستاگرام: haririandhariri

ایمیل: info@haririandhariri.com

LAVASAN VILLA, Gisue Hariri, Mojgan Hariri

Project’s Name ـ Function: Lavasan Villa, Residential

Office ـ Company: Hariri & Hariri Architecture

Lead Architect: Gisue Hariri, Mojgan Hariri

Design Team: Markus Randler

Associate Architect & Project Manager: Navid Ghasemi

Location: Lavasan,Tehran, Iran

Total Land Area ـ Area Of Construction: 930 m2, 1120 m2

Client: Ramin & Rana Varasteh

Date: 2011 - 2015

Photographer: Moein Hosseini

Website: www.haririandhariri.com

Email: info@haririandhariri.com

Perhaps the clearest answer to the question posed in the title is: *“Because this building knows how to defend itself!”* But before we recount the story behind this short sentence, we would like to refer to a theoretical perspective from Richard Neutra (1892–1970). In his book *Survival Through Design*, Neutra writes:

“\[…] A house can be designed like a monthly salary. In this case, satisfaction with the design is derived from habituation. But there is a completely different approach: designing for a sensation like the thrill of romance, designing for a moment, for a fraction of a second. \[We have seen that] the experience of an entire lifetime can be condensed into a few memories. This is closer to the latter approach to design: blending with the excitement of an event, as opposed to the first approach that deals with something fixed and tedious. The value of a wide sliding door opening to a garden lies in exactly this. \[…] In this complex world, the designer should not act solely based on pure aesthetic principles rooted in outdated assumptions. \[…] Whether we are aware of it or not, whether the created environment pleases or disturbs us, in any case, the sound of a room, as a complex acoustic phenomenon, even in its slightest resonances, has an effect on us.” (Neutra, 1954, cited in Mallgrave, 2016)

The phrase “This building knows how to defend itself”* was, in fact, the last sentence uttered by the client and owner of the Lavasan Villa, designed by the Hariri sisters, in a phone conversation with us. We had asked her to be present on the day the jury for the Building of the Year Award visited the site, emphasizing that since the architects were not in Iran, the depth of their work might not be fully grasped by the jury, and it would be best if the architects or she herself were there to provide explanations. Her reply was simply: *“This building knows how to defend itself.”

As it turned out, the first jury team, after visiting the building, insisted that the second team should also see the project, rather than relying solely on the reports and the final meeting. For fairness, the finalist projects were either visited by the full jury in one stage or visited twice.

So, what was the story? Apparently, the Lavasan Villa by the Hariri sisters had easily passed all the rigorous and profound criteria of the Building of the Year Award in Iran. Not only did the project fully meet the judging criteria, but it also went beyond them. The building was more than just a cantilevered form on Lavasan’s sloped terrain; its successive spatial explosions deeply impressed viewers. It stepped into realms of architectural value often overlooked or neglected in Iran.

On the surface, the interior decoration had been arranged with exceptional artistry, demonstrating the harmonious coexistence of “architecture and interior design”—a term that is slowly fading from our architectural vocabulary. Interestingly, despite the structural challenges, the building’s engineering had fully met the architects’ needs—an ideal condition that sometimes, unfortunately, is reversed, with architecture serving the structure instead.

“Your thinking is delicate, cold, beautiful, and majestic. The stones you have set tell me this. You draw my attention to that place, and my eyes behold it. They see something that reveals a thought—a thought that is not expressed through sound or speech, but only through shapes placed in a specific relationship to one another. These shapes appear clearly in the light. The relationships between them are not necessarily tied to usability or resemblance; they are the mathematical creation of your mind—they are the language of architecture. By using raw materials and starting from conditions somewhat dependent on utility, you have created specific relationships that have moved my emotions… This is architecture.” (Le Corbusier, 1923, cited in Balkhari, 2016)

In simpler terms, both Neutra and Le Corbusier, as modern architects—though famed for their white cubic machine-like forms—were deeply concerned with human space. They understood the power of architecture: the power to transform a mound of earth into an imaginative space. Through their writings, they sought to declare the manifestos of their works and to stress the necessity of a *spirit of architecture*. Their emphasis on human psychology and environmental awareness—and their attention to neuroscience, even when it was still in its infancy—shows that in studying the history of modernity in architecture, we have overlooked certain dimensions.

It is noteworthy that Richard Neutra came to Iran in the 1960s at the invitation of Houshang Seyhoun. His arrival coincided with Iranian architects opening their eyes to modern works. Yet they too erred, perceiving modernity solely in the white cube. No one paid attention to the psychological and neuroscientific principles present in Neutra’s work. We became familiar with him through exhibitions and lectures, unaware that he had authored numerous books emphasizing the importance of neuroscience in architecture. In the early 1950s, he put forth an idea far ahead of his time, calling on designers to become biologists—in other words, to focus not only on formal abstraction but also on the flesh, blood, and psychological needs of those who inhabit the built world.

Aside from the client’s famous sentence, there is a twist: the Hariri sisters did not consider their work in Iran to be worthy of this award. The neighboring plots to this property are empty, and looking at their steep, barren slopes only strengthened our belief in architecture’s power to create human space. One can partly guess why the Hariri sisters were modest about their work. They do not reside in Iran, and their image of the country was shaped not by postcards but by the internet. Even some locals today are influenced by virtual media, let alone those observing from the United States and visiting Tehran for only a few days each year. The Hariri sisters did not see their work as competitive compared to local projects, because some images broadcast of our architecture differ from reality. However, their client, who resides in Iran and likely consulted many offices before commissioning the work, knew the reality well. Both the architects and the client had little to say in self-promotion and entered the award process with professional discipline—despite, surprisingly, some architects claiming that an on-site visit was unnecessary.

In this award, being in architecture—and experiencing it through the senses with a focused, selective eye—was what mattered. This building has moved beyond current architectural norms in Iran and approached a world-class standard. One of the best descriptions of good architecture might be the criteria outlined by Juhani Pallasmaa, as quoted by Mallgrave in *The Architect’s Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture*. In his essay Six Themes for the Next Millennium (1994), Pallasmaa lists six points for reviving the enchantment of architecture: slowness, adaptability, sensuousness, authenticity, idealization, and silence. Along these lines, Pallasmaa writes about visual tactility:

“Architecture based on the eye analyzes and controls, whereas architecture based on visual touch unites and integrates.” (quoted in Mallgrave, 2010)

Pallasmaa himself, in his works, focuses on the depth of feeling rather than outward form. Therefore, architectural judgment should be carried out with the aid and focus of all the senses.

We believe that the Hariri sisters’ Lavasan Villa, rightfully chosen as Iran’s Building of the Year, carries multiple messages from different perspectives—but the best of them remains the one the client declared over the phone, with complete confidence and satisfaction: “This building knows how to defend itself!”

Our recommendations, based on the experience of the Building of the Year Award in Iran:

- Pay attention to global architectural knowledge, especially trends that are not superficial or fashion-driven but are rooted in deeper layers of world architecture.

- Move beyond architectural formalism, particularly when it leads to the elimination of human presence, increased costs, detachment from the realities of architecture, and harm to personal and national interests.

- Move beyond verbose but low-value architecture that attempts to justify itself with scattered statements far from the essence of architecture.

- Move beyond image-making in architecture, especially where attempts are made to “correct” a three-dimensional space by reducing it to a two-dimensional photograph.

- Move beyond purely formal aesthetics, especially those based on ancient patterns that have no place for contemporary space and future-oriented thinking. As aesthetic standards are often measured by Western cultural norms, they may even conflict with our sensibilities.

- Increase attention to new interdisciplinary knowledge in architecture education, particularly architecture informed by neuroscience.

- Promote architectural design based on human-centered criteria.

- Pay attention to multi-sensory architecture.

- Encourage experienced and skilled consulting engineers and other architectural sectors—often working on state projects without regard for global architectural discourse—to engage with contemporary currents in architecture.

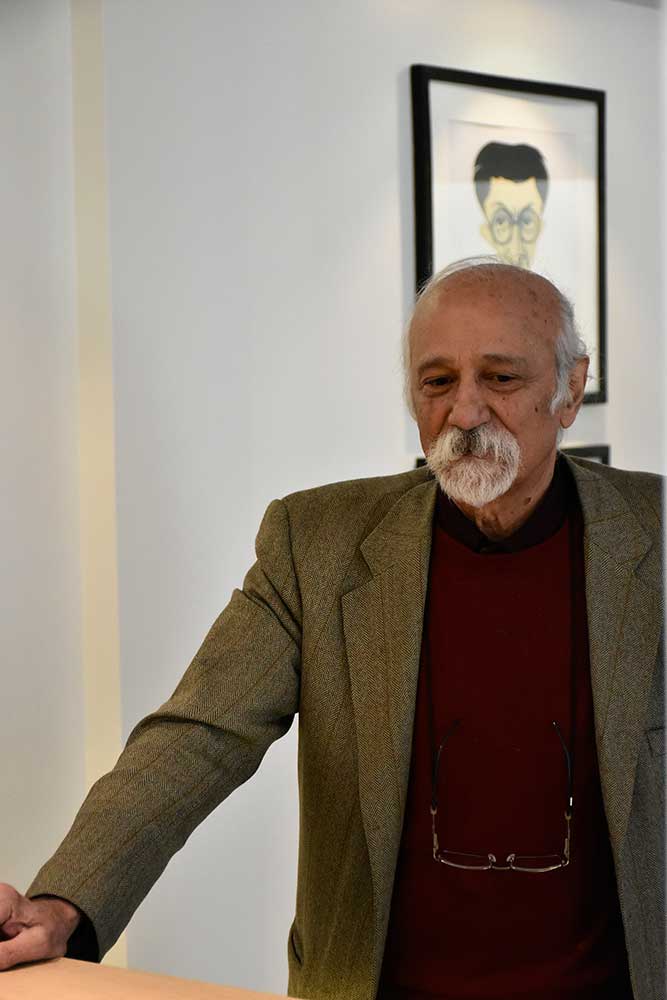

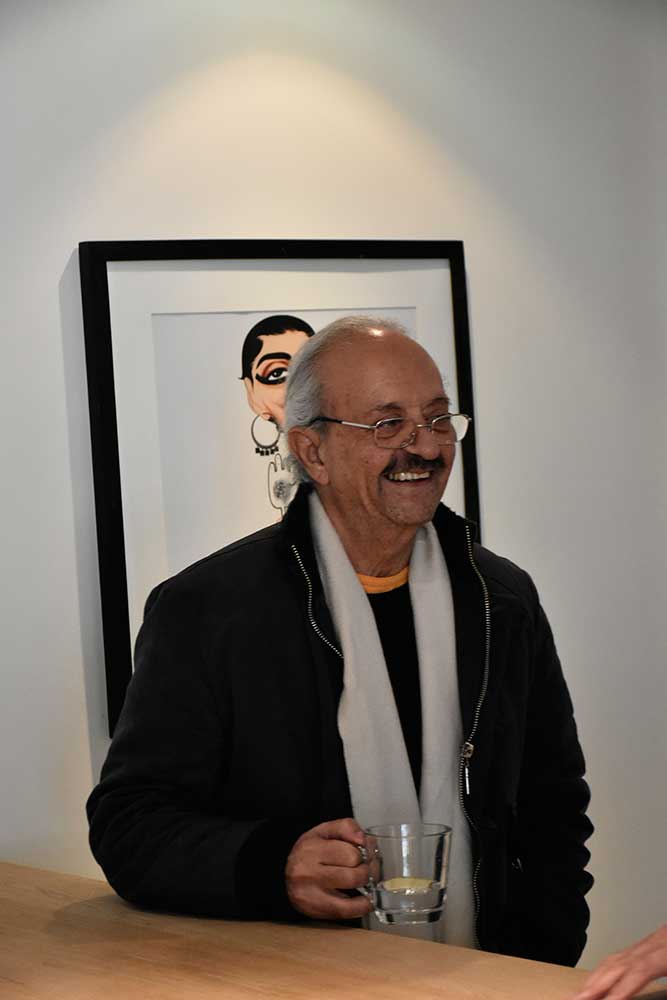

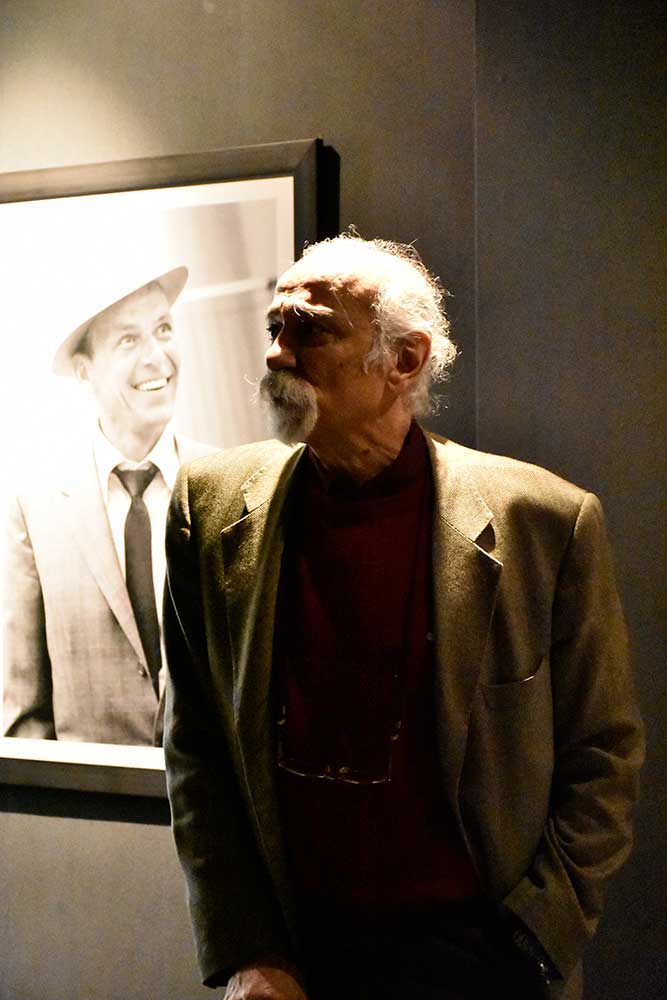

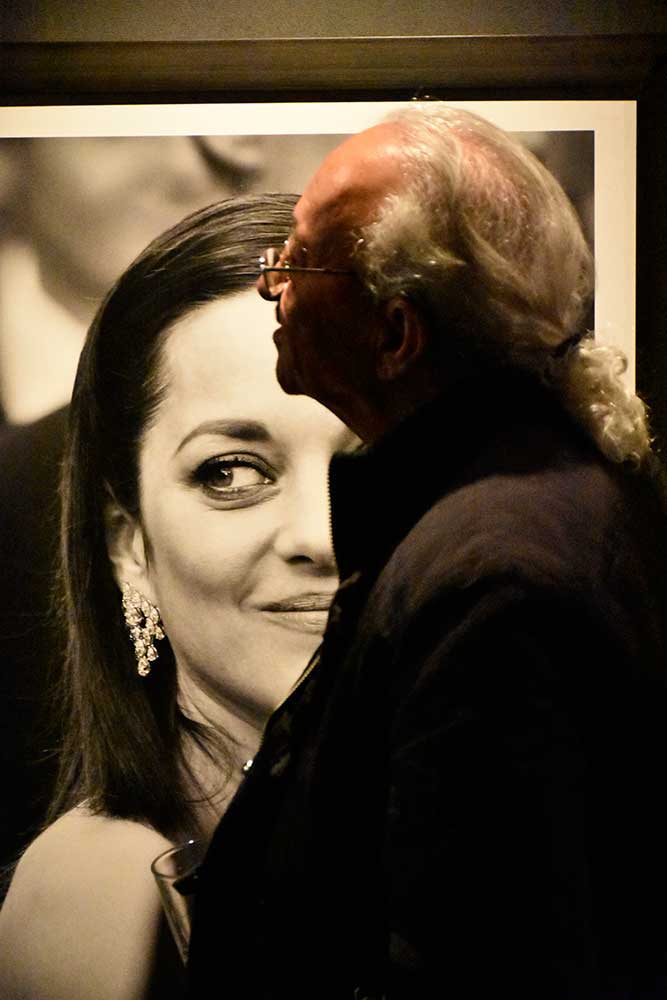

هیئت داوران اولین جایزهی ساختمان سال ایران، 1395:

دکتر سیروس باور، دکتر سیاوش تیموری، دکتر کوروش حاجیزاده، دکتر شیوا آراسته، مهندس عبدالرضا ذکایی

Jury of the First Iran Building of the Year Award (2016):

Dr. Sirus Bavar, Dr. Siavash Teimouri, Dr. Kourosh Hajizadeh, Dr. Shiva Arasteh, Engineer Abdolreza Zakaei

ایده طراحی