نان و نمک، تاملی در جایگاه تاریخی مقبره نادر، اثر هوشنگ سیحون

نوشتهی محسن اکبرزاده / دفتر طراحی پژوهی مشکات

The Historical Site of Nader Shah Afshar‘s Tomb, by Houshang Seyhoun

Written by Mohsen Akbarzadeh / Mishkat Design Research Office

![[عکاس: شهریار خانی زاد]](https://aoapedia.ir/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/SKH58461.jpg)

تنها یک بنای تاریخی میتواند تاریخی باشد. تنها کسی که در کادر عکس ایستاده باشد میتواند در عکس ایستاده باشد. این بدیهیات گاه معماهای بزرگی هستند، گاه آنقدر مبهوت و حیرت زدهایم که نمیتوانیم درک کنیم تنها فرزند از پدر ارث میبرد و نه غریبهها. تنها بنایی که خودش را در تاریخ خودش به جا آورده باشد میتواند خودش را تاریخی معرفی کند و بخشی از تاریخ معاصر و بعدتر تاریخ معماری یک سرزمین قلمداد شود. تمایز چنین بنایی با دیگر بناهای هم عصرش آن است که دیگران علیرغم فریباییها و زیباییها، علیرغم حیرت و تحسینی که در مخاطبان خود ایجاد کردهاند، هنوز برای آنکه بخشی از تاریخ قلمداد شوند، باید محک سنگین زمان را پشت سر بگذارند. اما بنای مورد اشاره ما، رابطهاش را با تاریخ بداهت بخشیده است، قطعی و محرز کرده است. وجدان عمومی را از تنگنای قضاوت درباره خودش رهانیده است. تکلیف همه چیز را مشخص کرده است و آدمها زمان گرفتن عکس یادگاری لازم نیست فکر کنند که چرا دارند این کار را انجام میدهند.

فهم تاریخی مستتر در آثار هوشنگ سیحون، کیفیتی را ایجاد کرده است که برای اهل نظر کمتر گفتگویی را ضروری میسازد. در تاریخ معاصر ایران شاید بتوان گفت معماری در این جایگاه با او شریک نیست که آثارش بیآنکه موضوع مجادله باشند، مورد تحسین واقع شدهاند. مخالف ندارد و کسی او را به جبر تاریخی متهم یا مفتخر نمیسازد. اما آنچه درباره کارهای سیحون مایهی تأمل است اقبال خواص و عوام در کنار یکدیگر است. رخدادی که جز برای برج شهیاد حسین امانت، به تقریب برای هیچ اثر دیگری در سدهی اخیر واقع نشده، چه برسد برای عمده کارهای یک معمار. چنین کیفیتی چگونه حادث میگردد؟ کار منتقد شاید همین شناسایی راز گل سرخ باشد. تلاشی گاه متلاشی که میخواهد نورهای مهیج صحنه را خاموش کند و پرده کتان را از روی هیبت رازگونه تندیس، کنار بزند تا بداند پس و پشت هر تقدسی چه نهفته است. اینجا همان آوردگاهی است که مجادله تاریخی عارفان پدیدارشناس با فلاسفهی گونهشناس آغاز میشود. جدال بر سر یکتایی یا همانندی، اصالت یا تناوب تاریخی، شعبده یا هوشمندی.

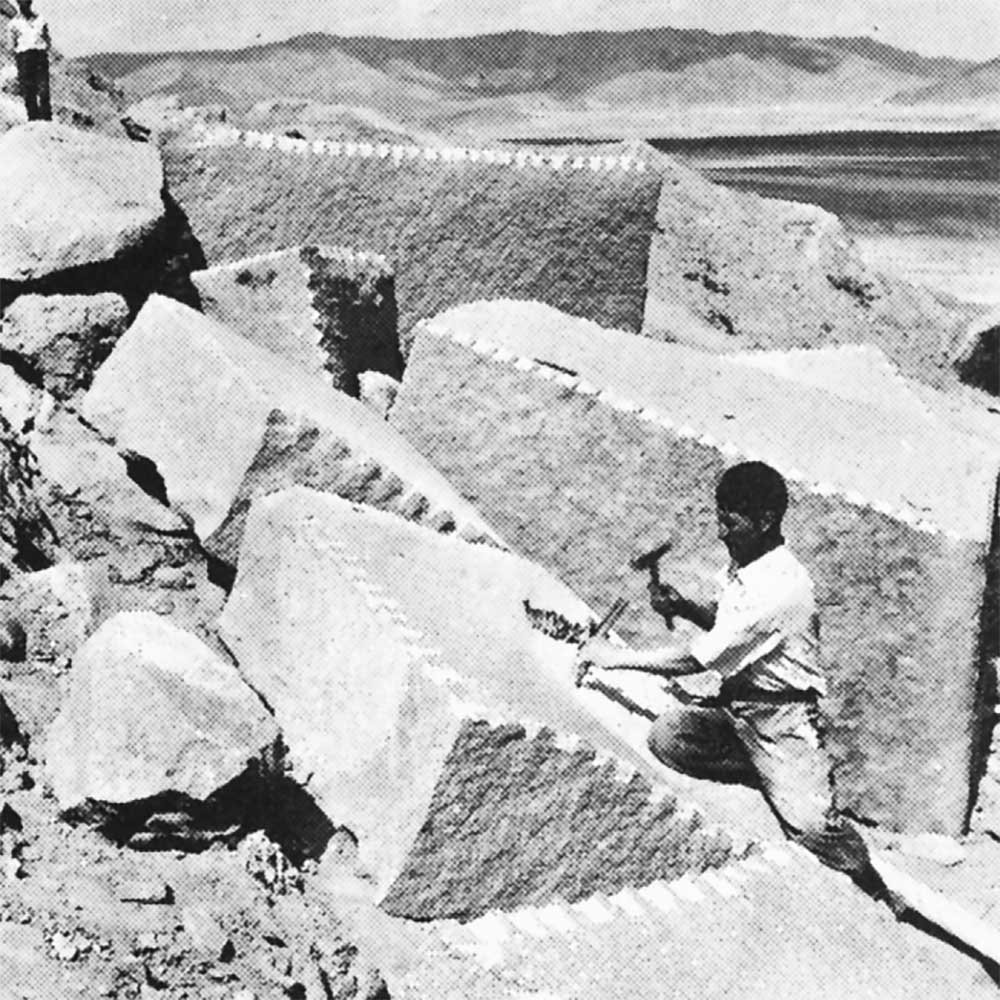

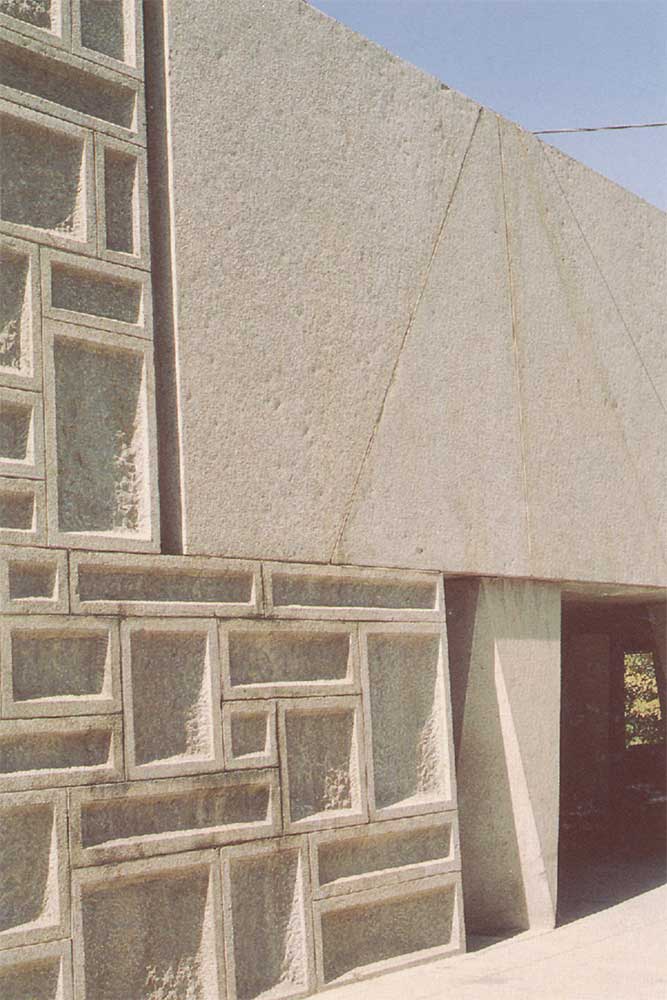

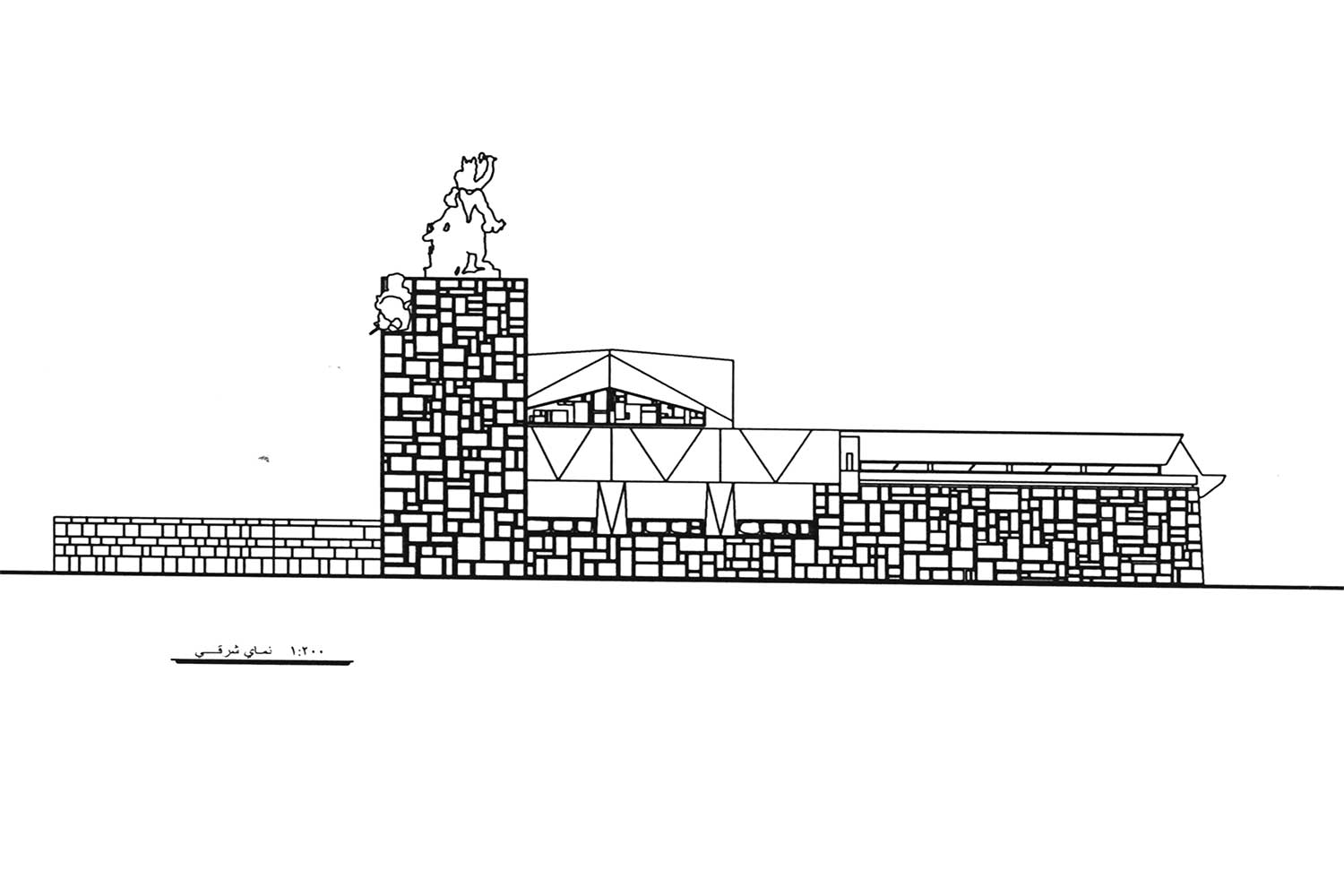

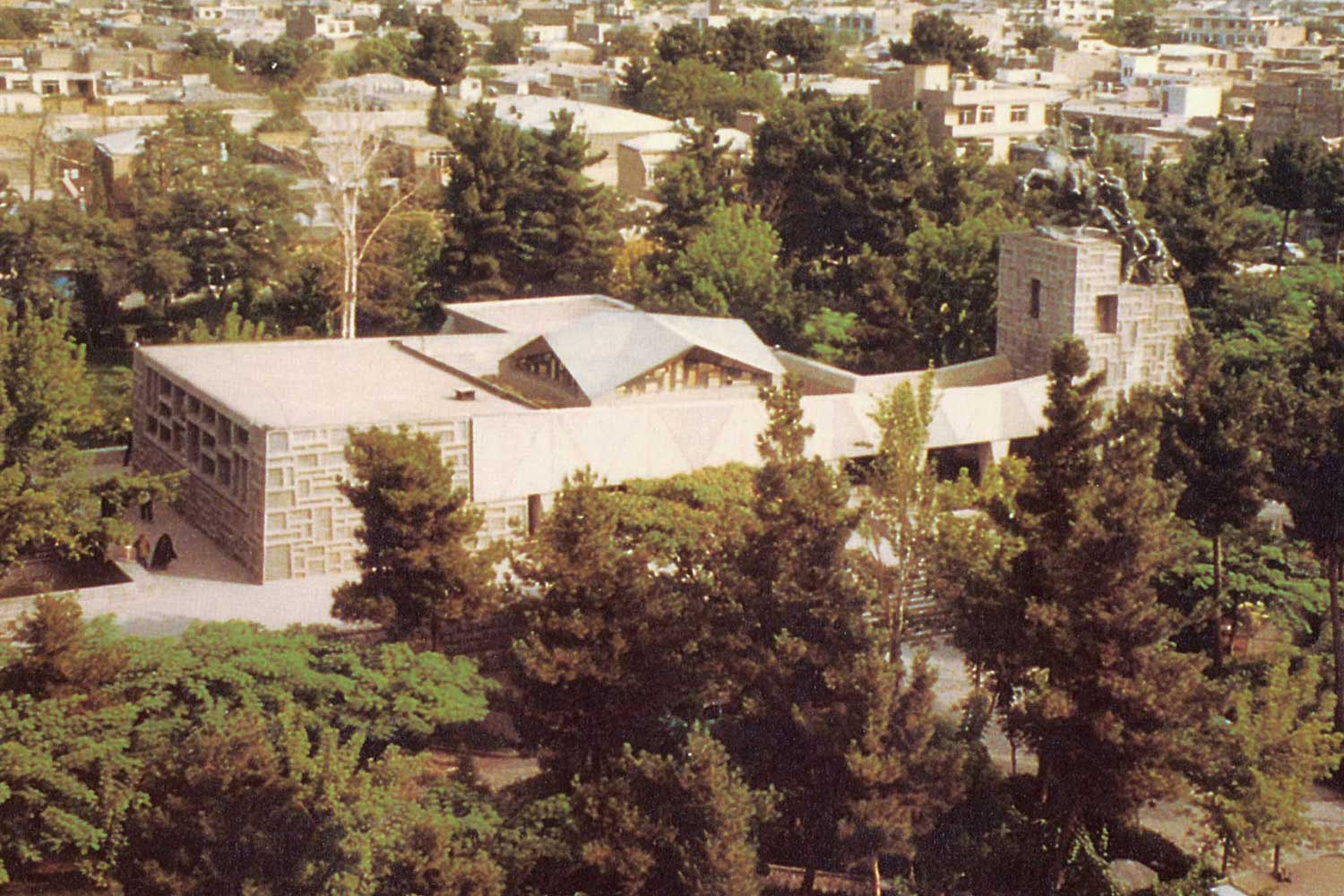

تنها یادگاریام از نخستین سفر زیارتی به مشهد در ایام کودکی، عکسی است بر پلههای مقبرهی نادر، که با رزم جامهای کودکانه و کرایهای، سپر و شمشیری که به زحمت توی دست نگاه داشتهام و آفتابی که زورش به مچاله کردن چشمهایم رسیده است، سعی دارم در هیبت یک قهرمان دیده شوم. سالها مرور این تصویر همواره بُعدی از تبسم به چهره تصنعیام، تماشای هیبت سنگی بنایی بوده که در یک صبح زود تابستانی مایهی کنجکاویام واقع شده است. در گوشم چنین مانده که اینجا خیمهگاه نادر است و همان چادری است که او در آن به قتل رسیده است! سالها بعد ولی آن اقوال را خردمندانهتر باز شنیدم. اینکه معمار چیرهدست تاریخ بلد، فضای خیمهگاه نادری را دستمایهی مقبره او ساخته و به خاطر بازنمایی شخصیت نادر، از سنگهای بومی منطقه بهره جسته و این پایه مجسمه رفیعی که مشاهده میشود، استعارهای است از جایگاه رفیع او در تاریخ ایران. این سخنان تسکینبخش و خوشایندند، مجادلهای را بر نمیانگیزانند. همه فهماند و چه اینکه به نقل صریح از خود معمار نیز مزیناند و پارههای خیال راهنمایان گردشگری نیستند.

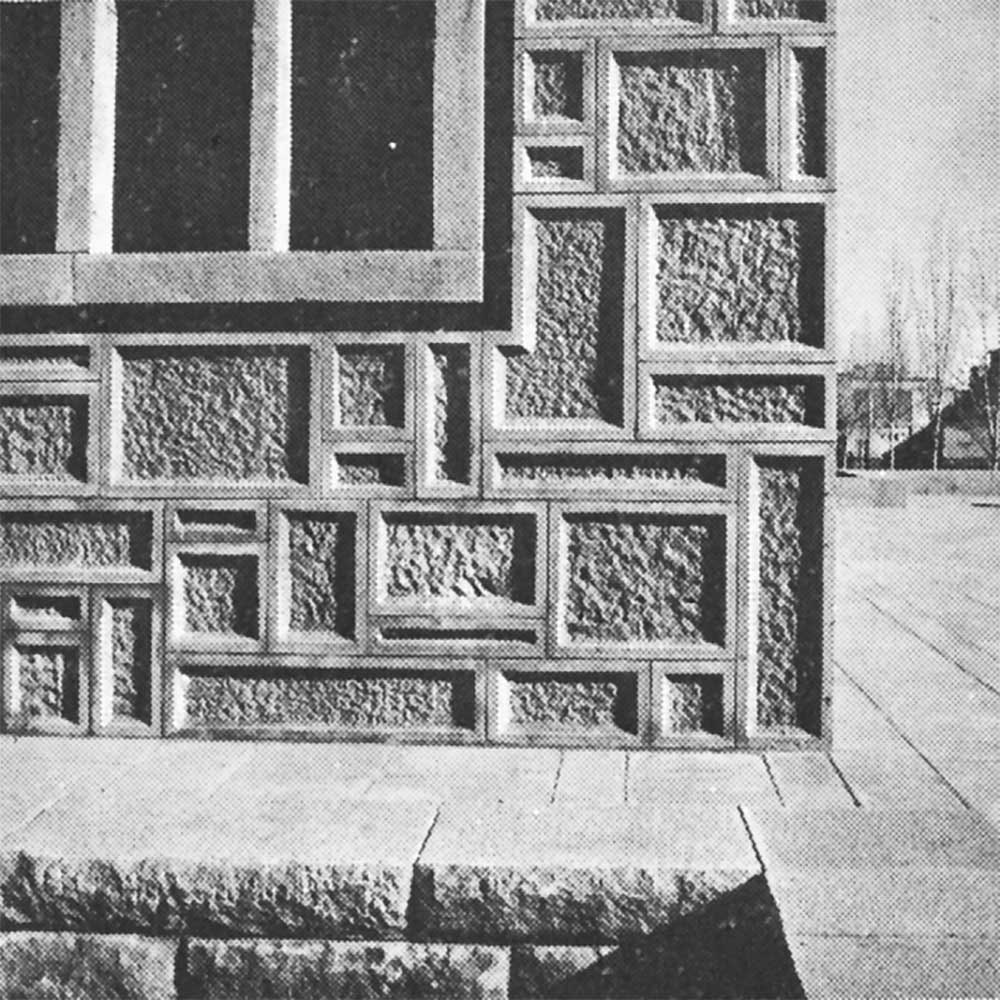

در این چند سال اخیری که در مشهد ساکن شدهام، درکم از این بنا سادهتر و روشنتر شده است. تماشای مستمر تمام آثار سیحون در خراسان کنار یکدیگر از جمله ابنیه مجاور مقبره فردوسی، مقبرههای خیام و کمالالملک، مقبره ابنیمین فریومدی و خود مقبره نادر، به علاوه تجربه تماشای مفصل مقبره پورسینا در همدان، مرا متوجه این نکته ساخته که او چگونه توازن میان شباهت و تفاوت را رعایت میکرده است. اینکه سنگ و بتن در عمده آثار معماری او دستمایهی اصلی است، این قول را که به خاطر تجلیل و تجلی شخصیت نادر در مجموعه به کار گرفته شده برای من از صرافت میاندازد. چه اینکه سیحون نقاش، برخوردش با سنگ بسیار مبتنی بر “افه” است. لفظی که در حافظه آموزشی دانشکده هنرهای زیبا، کلاسیک شده است. افههایی که او در کار سنگ به کار میبندد، در مقبره همدان و رستوران توس و خانههای تهران نیز به نحوی تکرار میشود. حتی فراتر از مصالح و بافت، میتوان تکرار بارزههای فرمی را نیز در آثارش جستجو کرد. ستون رفیع مقبره نادر، عیناً برگرفته از خانه کاظمی تهران است و حتی در ترکیب با بقیه حجم نیز همان موقعیت را دارد، پنجرهها نیز سالها بعد خود را در توس تکرار کردهاند.

هرچند این آوردههای جزئی، نوآوریهایی است که بعدها در چند نسل از کار معماران ایرانی تکرار شد و به خودی خود میتواند بهعنوان امضای طراحی سیحون قلمداد شود، ولی وجه فروگذاشته شده در این پروژه ارجاعات تاریخی آن است. هرچند میدانیم برج بلند مقبره بوعلی به برج قابوس بن وشمگیر اشاره دارد و یا مقبره خیام و چه چه؛ اما درباره مقبره نادر سخن از چنین ارجاعاتی وجود ندارد و داستانها حکایت از آن میکنند که صورتبندی بنا مبتنی بر کانسپتهای روایی است. بیآنکه ضرورت داشته باشد تاثیر حقیقی یا ادعایی چنین کانسپتهایی را به نقد بکشیم، میتوانیم بسیار ساده، چشمها را دوباره بشوییم و به این بنای ستودنی نگاه کنیم:

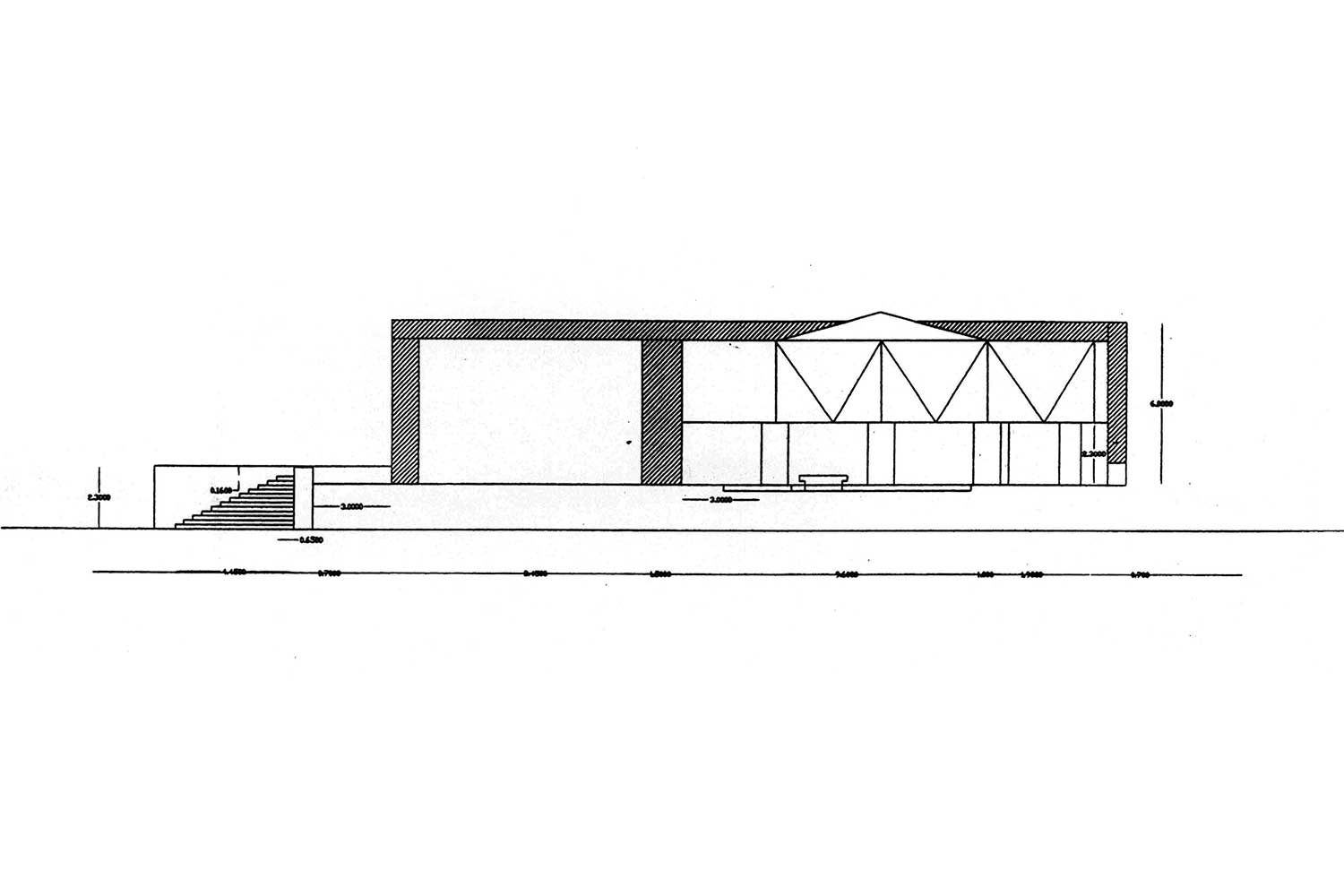

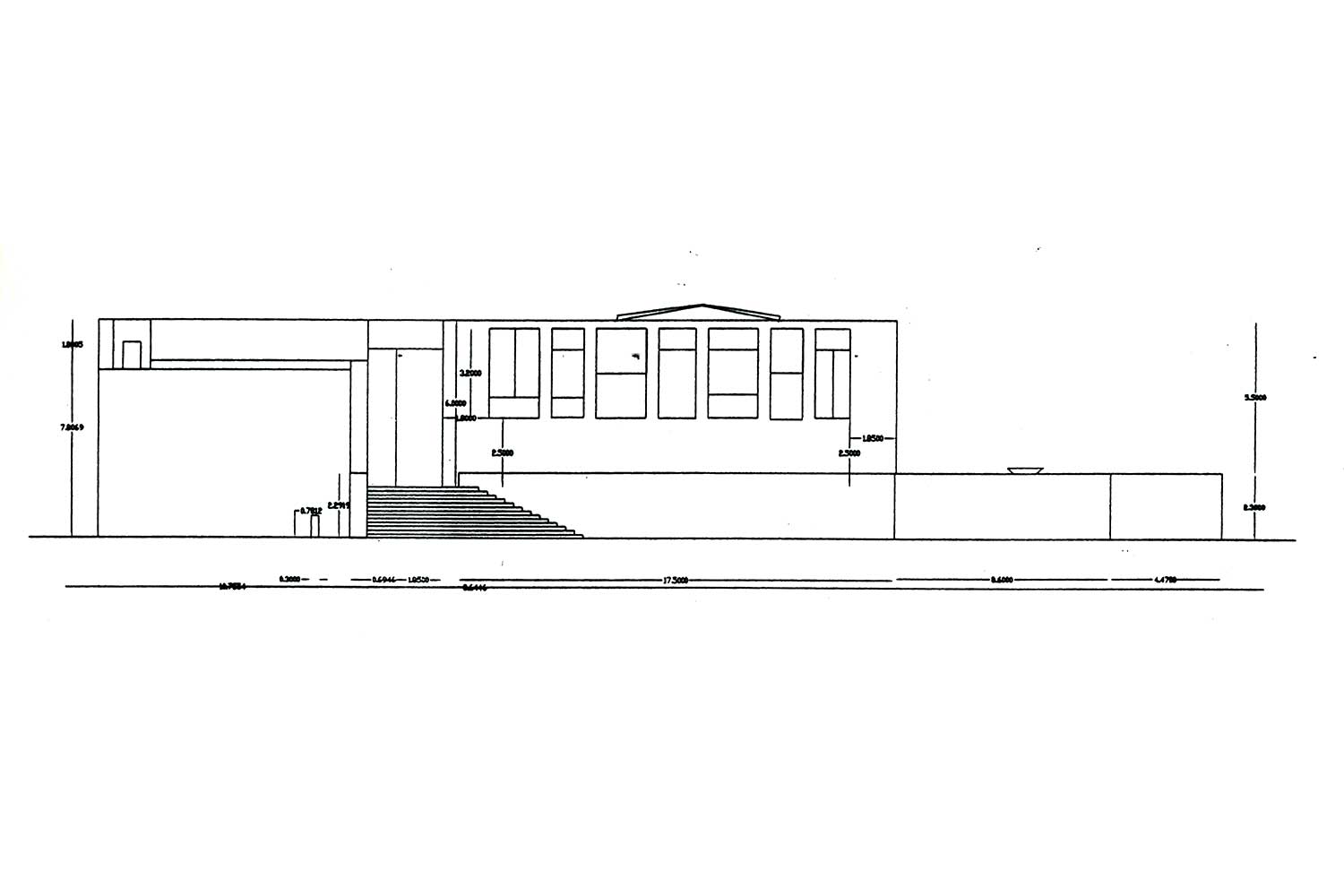

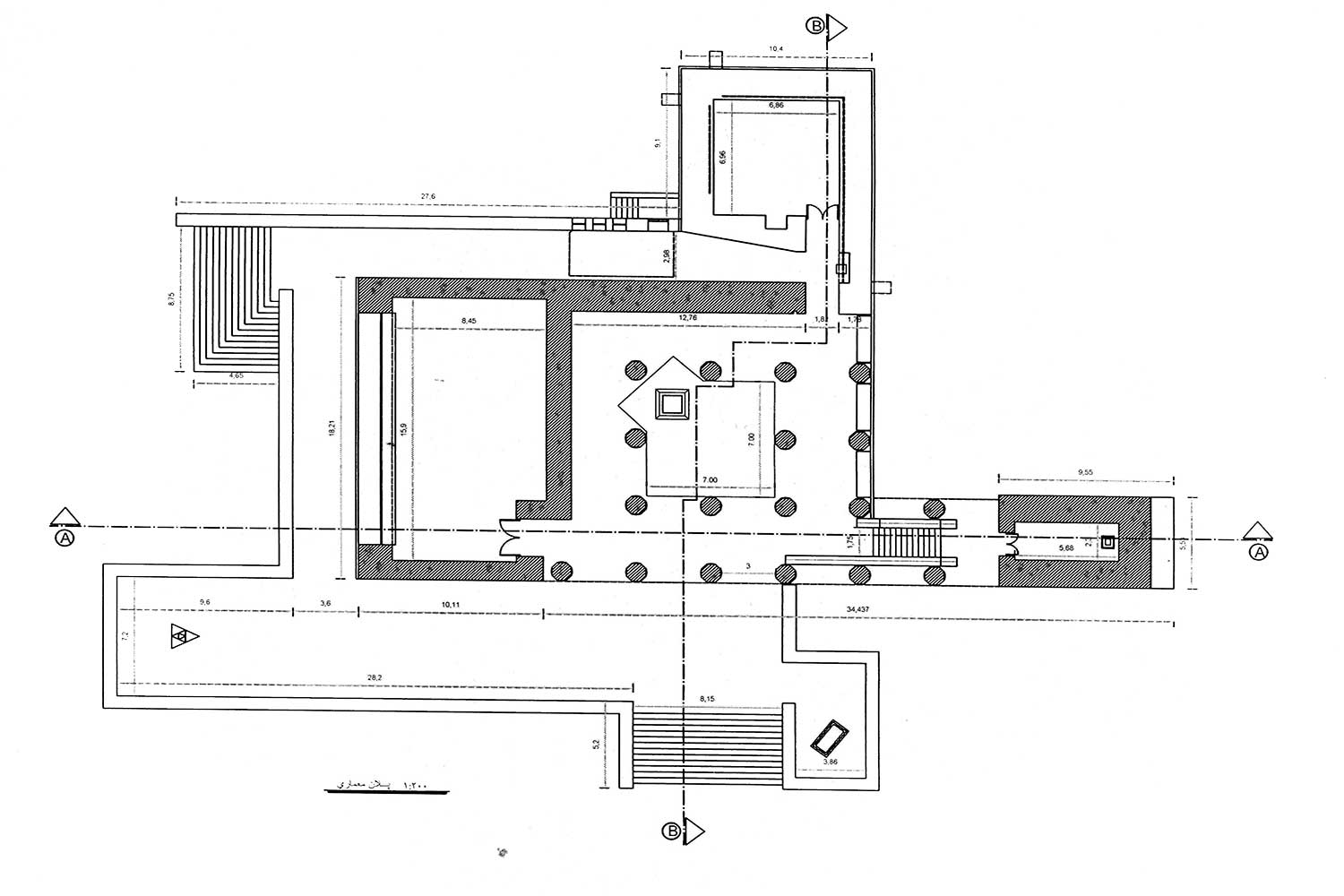

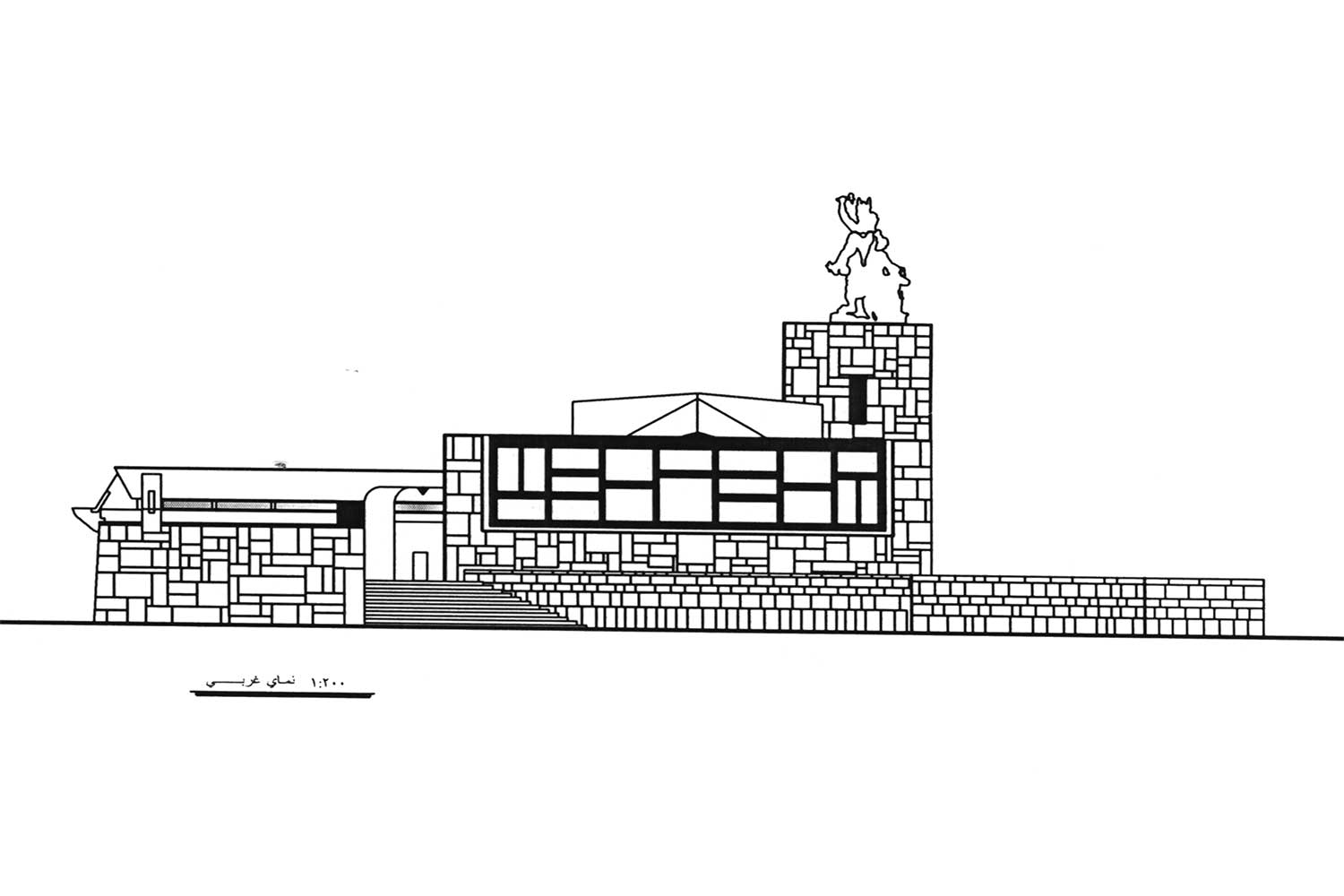

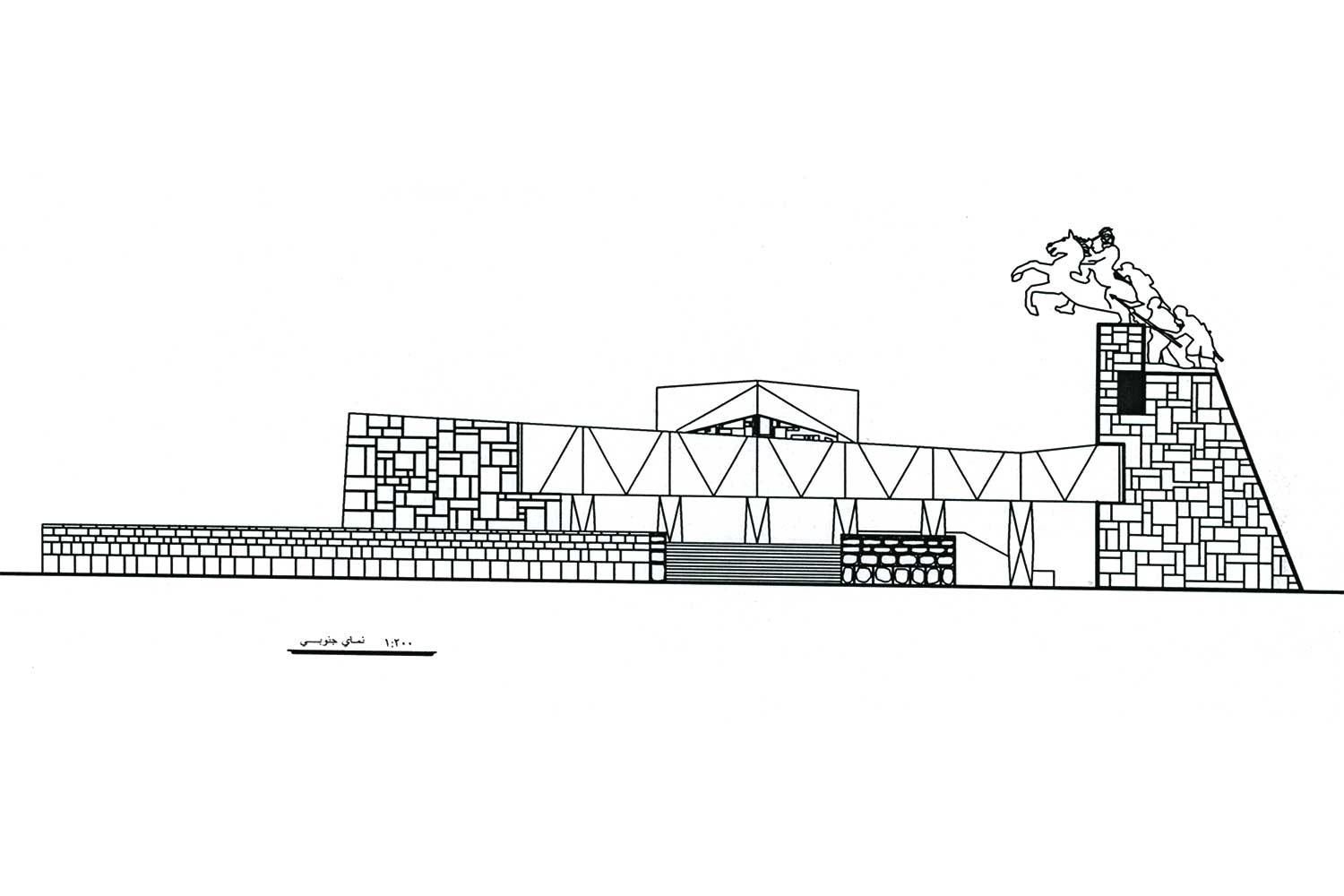

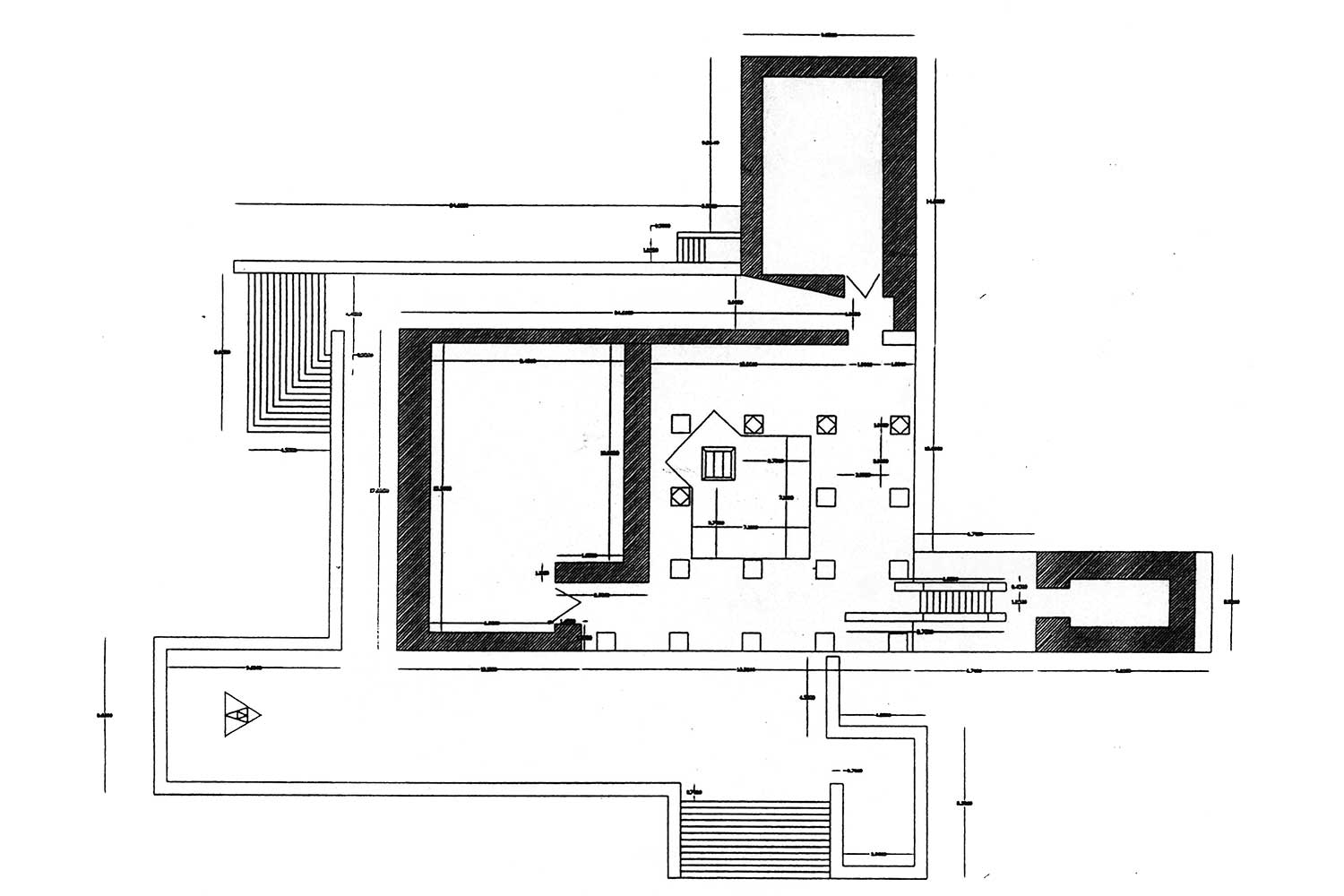

ورودی اصلی بنا، که پیکرهبندیاش را میتوان کاملاً منطبق با ایوان مقبره پیشین نادر به حساب آورد، یک ایوان است. با همان خواص ایوان در معماری ایرانی، که با تغییر مصالح خود را از بقیه جبهه بنا جدا می کند. تردستی سیحون اما در اینجا آن است که سطح چشمگیرتر و حائز بافت را به جدارههای کناری بخشیده و پوست ایوان را عریان و ساده کرده است، تجربهای که در مقبره همدان نیز به چشم میخورد.

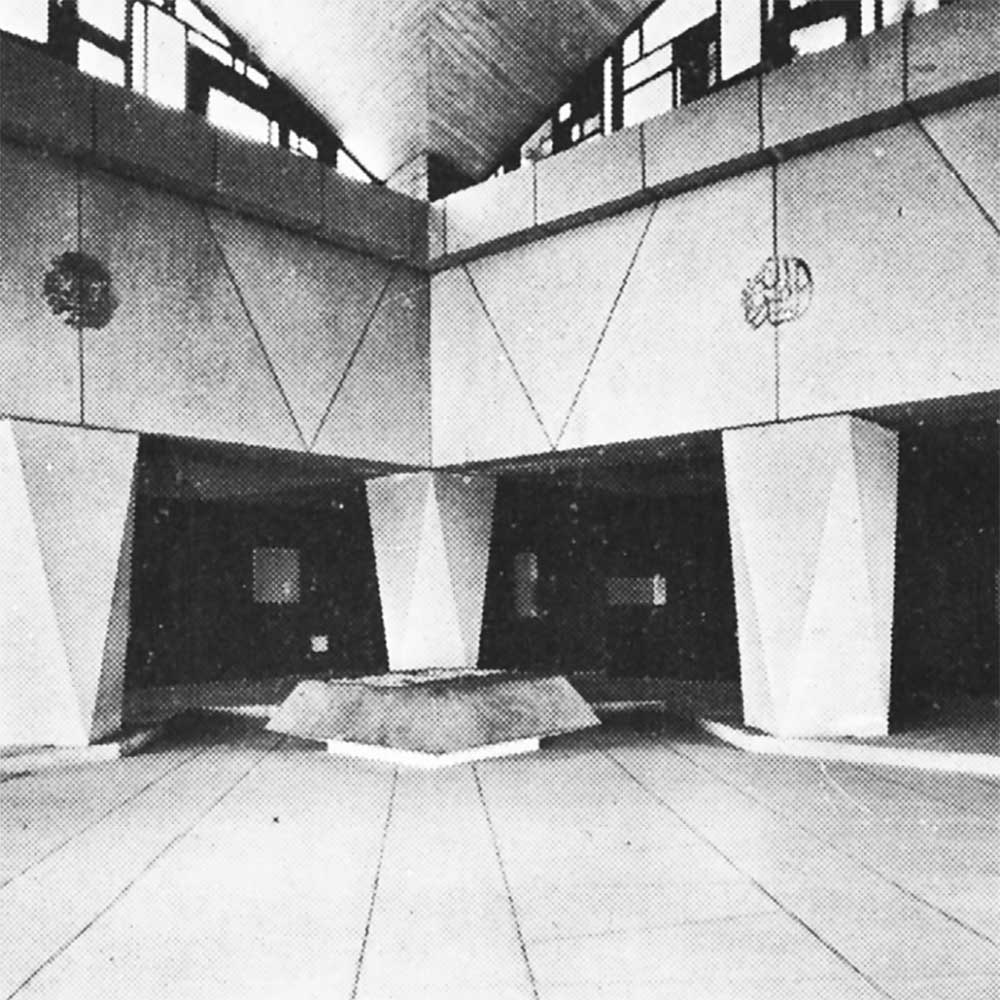

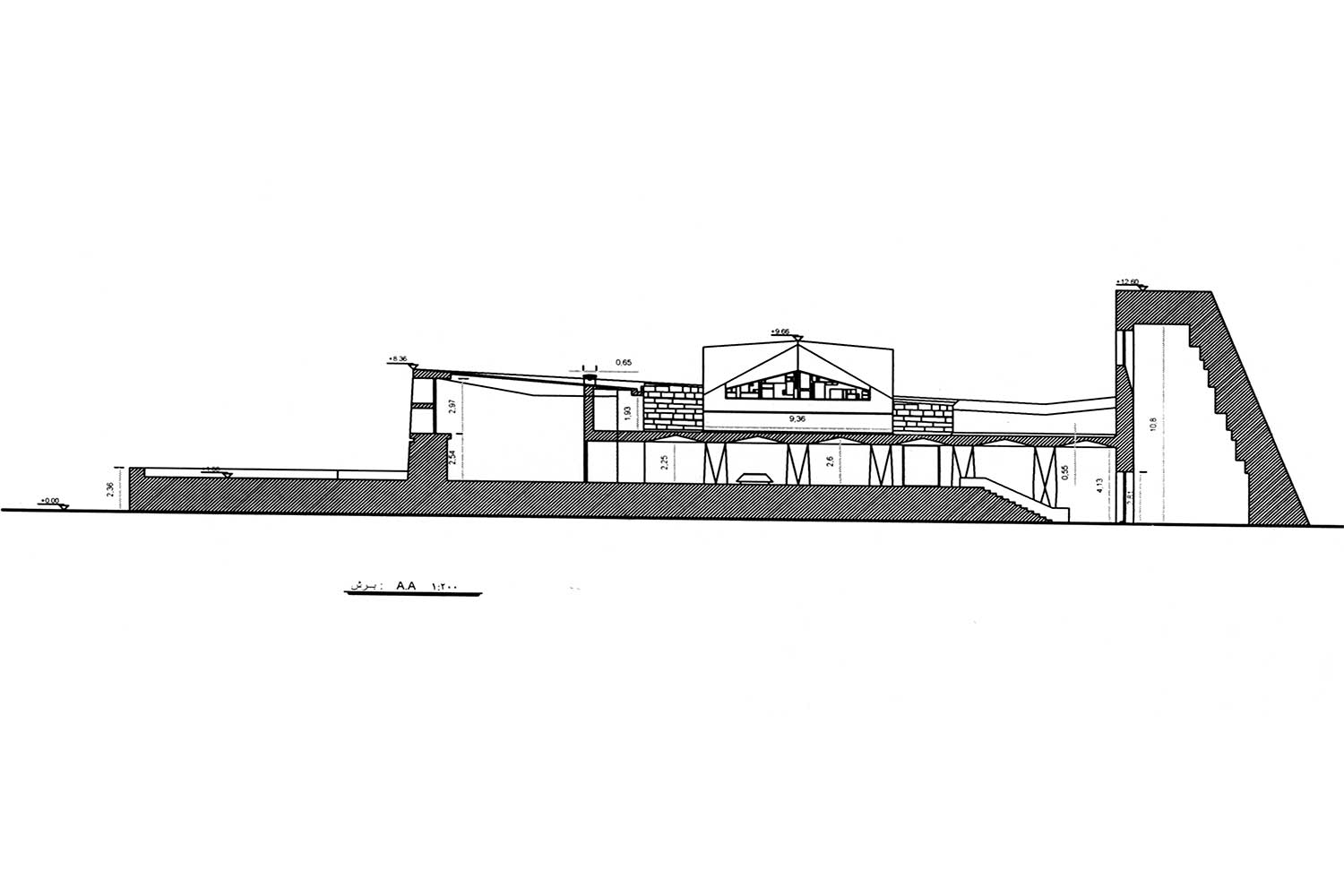

فضای اصلی یک گنبدخانه است. با همان نظام سازهای ترکبندی گنبدهای ایرانی که قطاعها، بار سازه را به شانههای هم تکیه میدهند و به حلقه فشاری ذیل خود وارد میسازند. به همان ترتیب نیز، فضای غیرباربر میان قطاعها، میتوان نورگیر واقع شود. چنانکه در شیخ لطفالله به خاطر مخاطب میآید و البته که بسیاری دیگر از گنبدهای ایرانی.

رواقهای کنار رواقاند. تالار و دالان و یا هر اسم دیگری که در ازنای هندسیاش، فردی را از فضایی به فضایی منتقل کند. با همان طاقهای متوالی چهاربخشی که در سنت رواقسازی ما دیده میشود. مسجد وکیل، شیخ لطفالله، کاروانسرای مادرشاه و چه بسیار نمونههای دیگر.

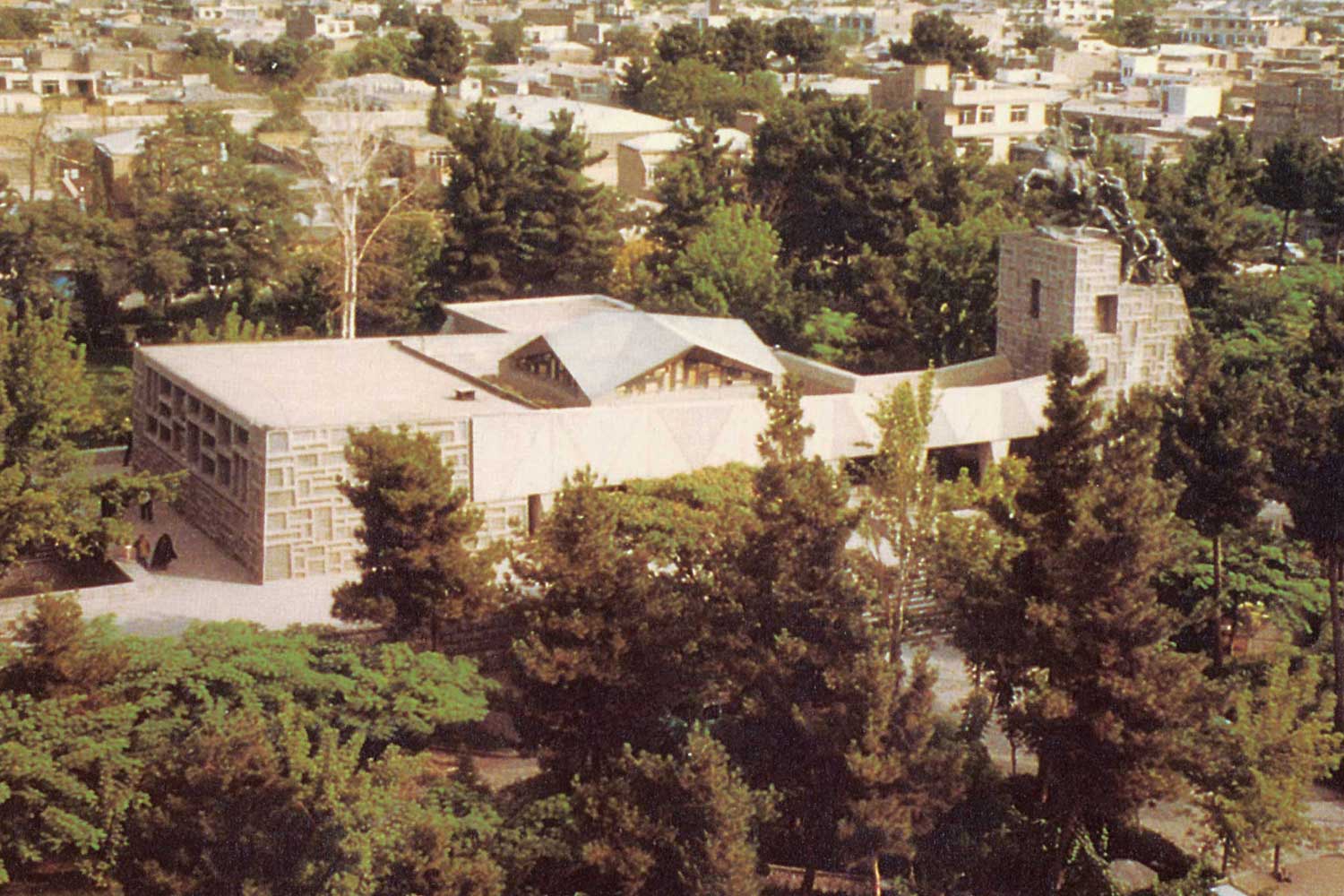

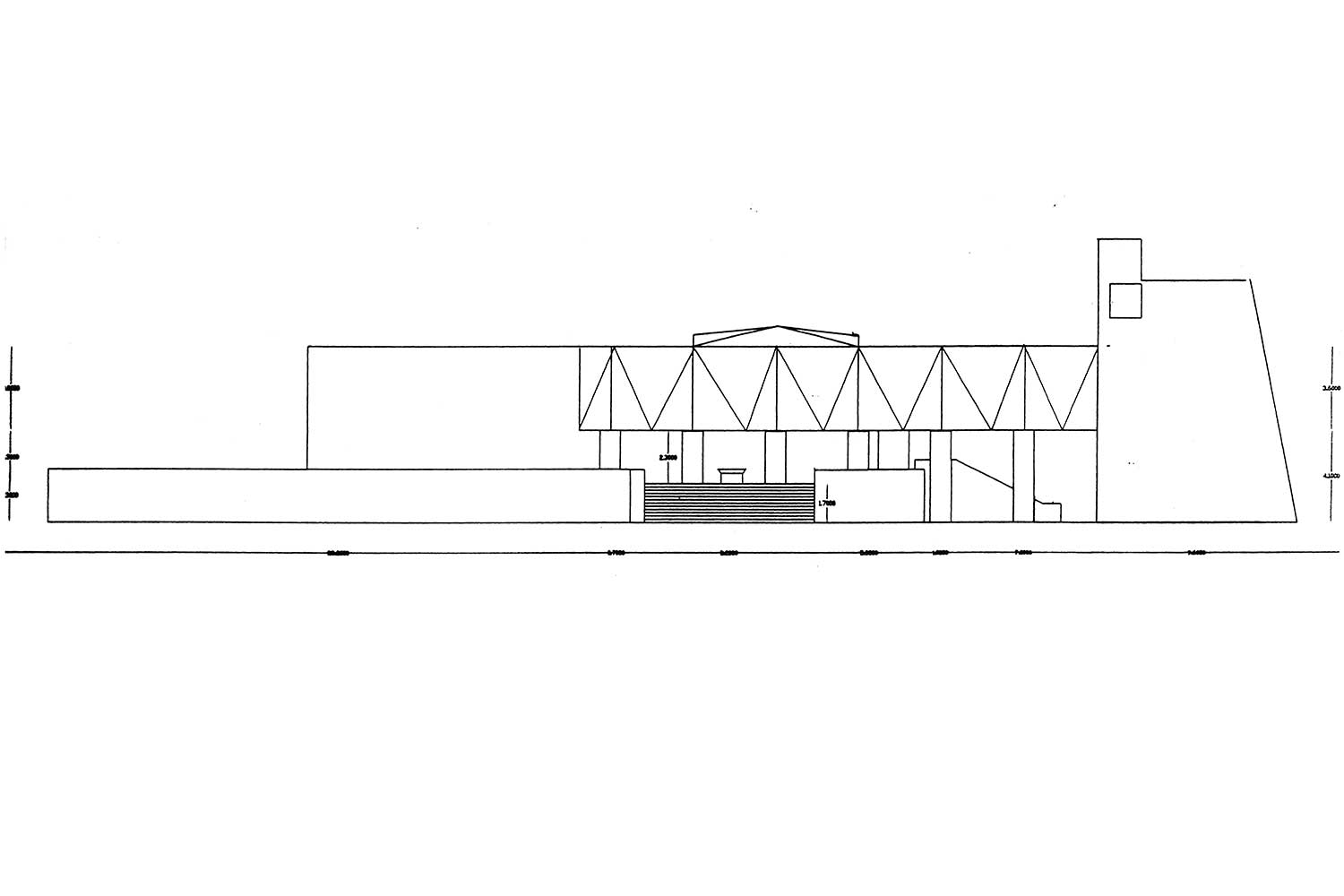

ستون به افراز رفته مجسمهی نادر و هم رزمانش، در ترکیببندی کلی بنا، دقیقاً نقش تک منارههای معماری ایران را ایفا میکند. با همان خواص. یعنی اتاقکی در پایه، روزی در بالا، سادگی بدنه، و تزئنیات و جلوهگری در تاج گلدستهها که در اینجا نقشش را مجسمهها بر عهده گرفتهاند.

نکته مهمتر اما همنشینی این عناصر در کنار یکدیگر است. مناره، ایوان، گنبد و رواقها در کنار یکدیگر، یک ترکیببندی تماماً ایرانی را ایجاد میکنند. سیحون هرچند در به کارگیری عناصر و جزئیات و محصول بصری نهایی، نوگرایی را تکلیف خود میداند اما از سرمایه عظیم الفت دست نمیکشد. او مقبرهای را به سیاق دیگر مقبرههای ایرانی صورتبندی میکند که میتوان برای آن مثالهای متعددی برشمرد از جمله ارسنهای نطنز و بسطام. او به هیچ وجه خود را وارد ریسک یک ترکیببندی ناآزموده نمیکند و چنین کاری را نیز فخر به شمار نمیآورد. آرامش او در پذیرفتن سنت سبب شده تا بتواند پای خود را کنار سفرهاش دراز کند. برخلاف یقهگیریها و دشنامپرانیهای بسیاری از شاگردان بعدیاش، او دلیلی برای مرافعه ندارد. میراثدار است و سهم خود را گرفته است. زندگی خودش را میکند و نیازی به رقابت با تصورات بدخواهان و یا پاسخدهی به انتظارات همدلان ندارد. این استادانهترین طریق مواجه با سنت است. نان از تو و نمک از من. سفرهای اشتراکی که هرچه هست از همه است و برای همه. هوشنگ اشتباه نادر را تکرار نمیکند. اشتباه اویی که بر گذشته شورید و آینده را کور کرد. لهیبی یک نفره که انجامی جز تاریکی نداشت. همان تاریکی که در گنبدخانه مقبرهاش، در ذهن مخاطب عام، یادآور خیمه گاهی است که قتلگاه او شد.

Only a historical building can truly be called historical.

Only the one standing within the frame of a photograph can truly be said to stand in it. These self-evident truths are, at times, immense riddles. Sometimes we are so bewildered that we fail to grasp the obvious: only a true heir inherits from the father — never the stranger. Only a building that has inscribed itself within its own history can declare itself historical, becoming a part of the living chronicle of its era — and, in time, of a nation’s architectural memory. The distinction between such a building and its contemporaries lies precisely here: others, despite their charm and beauty, despite the admiration they may arouse, must still endure the heavy trial of time before they can be accepted into history. But this particular building has already affirmed its pact with history; it has sealed it, made it manifest. It has freed public conscience from the burden of judgment. It has resolved everything so decisively that visitors, when posing for a souvenir photo, no longer wonder *why* they are doing so. The historical consciousness embedded in the works of Houshang Seyhoun creates a quality so self-evident that it rarely requires debate among connoisseurs. In Iran’s modern history, perhaps no other architect shares this position with him — his works are admired, not argued over. He has no opponents; no one accuses or praises him as the mere product of historical inevitability. Yet what is most striking about Seyhoun’s work is the harmony of elite and popular reception: both the learned and the ordinary revere him alike. This convergence — achieved by almost no other modern Iranian monument except Hossein Amanat’s Shahyad Tower — is in itself extraordinary. How does such a phenomenon occur? Perhaps the critic’s task is to decipher this secret — to unveil the mystery of the rose. A labor both luminous and exhausting: an effort to dim the dazzling stage lights and lift the linen curtain from the statue’s sacred silhouette, seeking to see what lies beneath every sanctity. Here begins that age-old struggle between the phenomenological mystic and the typological philosopher — the quarrel between uniqueness and resemblance, between authenticityand historical recurrence, between magic and intellect. My only keepsake from my first pilgrimage to Mashhad in childhood is a photograph on the steps of Nader Shah’s mausoleum. Dressed in a child-sized, rented warrior’s costume, with a toy shield and sword barely held in my hands, and the sunlight forcing my eyes into a squint, I try to look like a hero. Over the years, that image has always drawn a faint smile to my face — not for the boy’s pose, but for the stone majesty of the building that captivated me on that bright summer morning. I remember hearing that this was Nader’s tent — the very one where he was killed! Years later, I learned the wiser version: that the architect, deeply versed in history, had designed the space of Nader’s tent as the conceptual core of his tomb; that he used the region’s native stones to evoke Nader’s character; and that the tall pedestal of the equestrian statue symbolized his elevated place in Iranian history. These interpretations are comforting, persuasive — not controversial. They are easily grasped, and even corroborated by the architect’s own words, not mere tour guides’ fancies. In these recent years living in Mashhad, my understanding of this monument has become simpler — and clearer. Seeing all of Seyhoun’s works in Khorasan together — from the Tomb of Ferdowsi to the Mausoleums of Khayyam, Kamal al-Moluk, and Ibn-Yamin Farumadi, along with the Avicenna Mausoleum in Hamedan — has made me realize how delicately he balanced similarity and difference. The recurring presence of stone and concrete in his designs convinces me that the material’s use in the Nader complex was not solely symbolic of Nader’s ruggedness. For Seyhoun the painter, the handling of stone was always performative — what the Fine Arts School would call an “effet”, a calculated gesture. The same “effects” of his stonework appear in the Avicenna Tomb, Tous Restaurant, and houses in Tehran. Beyond material and texture, even formal motifs repeat: the towering column of the Nader tomb recalls the Kazemi House in Tehran, identical in its compositional role, while the same window patterns reappear later in Tous. Though such formal inventions became influential for generations of Iranian architects — and thus may serve as Seyhoun’s design signature — the historical references in this project have often been overlooked. We know the Avicenna Tower nods to the Qabus Tower, and the Khayyam Mausoleum to other precedents, but no such lineage is claimed for Nader’s. Accounts suggest it was instead shaped by narrative concepts. Yet without disputing those narratives, we can simply cleanse our gaze and look anew at this admirable structure. The main entrance, clearly recalling the iwan of Nader’s earlier tomb, is indeed an iwan in the classical sense — differentiated by material and projecting from the façade. Seyhoun’s ingenuity lies in simplifying the iwan’s skin while granting its flanking walls the richer textures — a device also seen in the Avicenna Mausoleum. The central space is a domed chamber, following the structural logic of Iranian domes: segmented ribs distributing the load onto pendentives, with the interstitial spaces left open for light — as in Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque and countless others. The side halls, or riwaqs, connect spaces through a rhythmic series of four-part vaults, echoing the long tradition of Iranian arcades — from Vakil Mosque to Madar-e-Shah Caravanserai. The column bearing the equestrian statue of Nader and his companions serves, in compositional terms, as the building’s solitary minaret — with the same typology: a chambered base, a lookout above, plain shafts, and ornamental culmination. Most crucial, however, is the harmony among these elements — the iwan, dome, riwaqs, and minaret together forming an unmistakably Iranian composition. Though Seyhoun’s vocabulary is modern in form and detail, he never severs himself from the immense lineage of intimacy and continuity. His mausoleum follows the logic of Iran’s funerary ensembles — like Natanz or Bastam — without venturing into untested combinations or claiming novelty as a virtue. His serenity lies in accepting tradition — sitting comfortably at its shared table. Unlike many of his later disciples who clashed with the past in arrogance or discontent, Seyhoun found no need for rivalry. He was an heir, not a rebel; he took his rightful portion and lived his life without seeking to outshine enemies or satisfy admirers. This, perhaps, is the most masterful way to face tradition: bread from you, salt from me. A shared table, belonging to all. Houshang does not repeat Nader’s mistake — that furious rebellion against the past which blinded the future. A lone flame that ended only in darkness — the same darkness that, within the domed chamber of his tomb, still evokes in the common visitor’s mind the dim tent where he met his death.

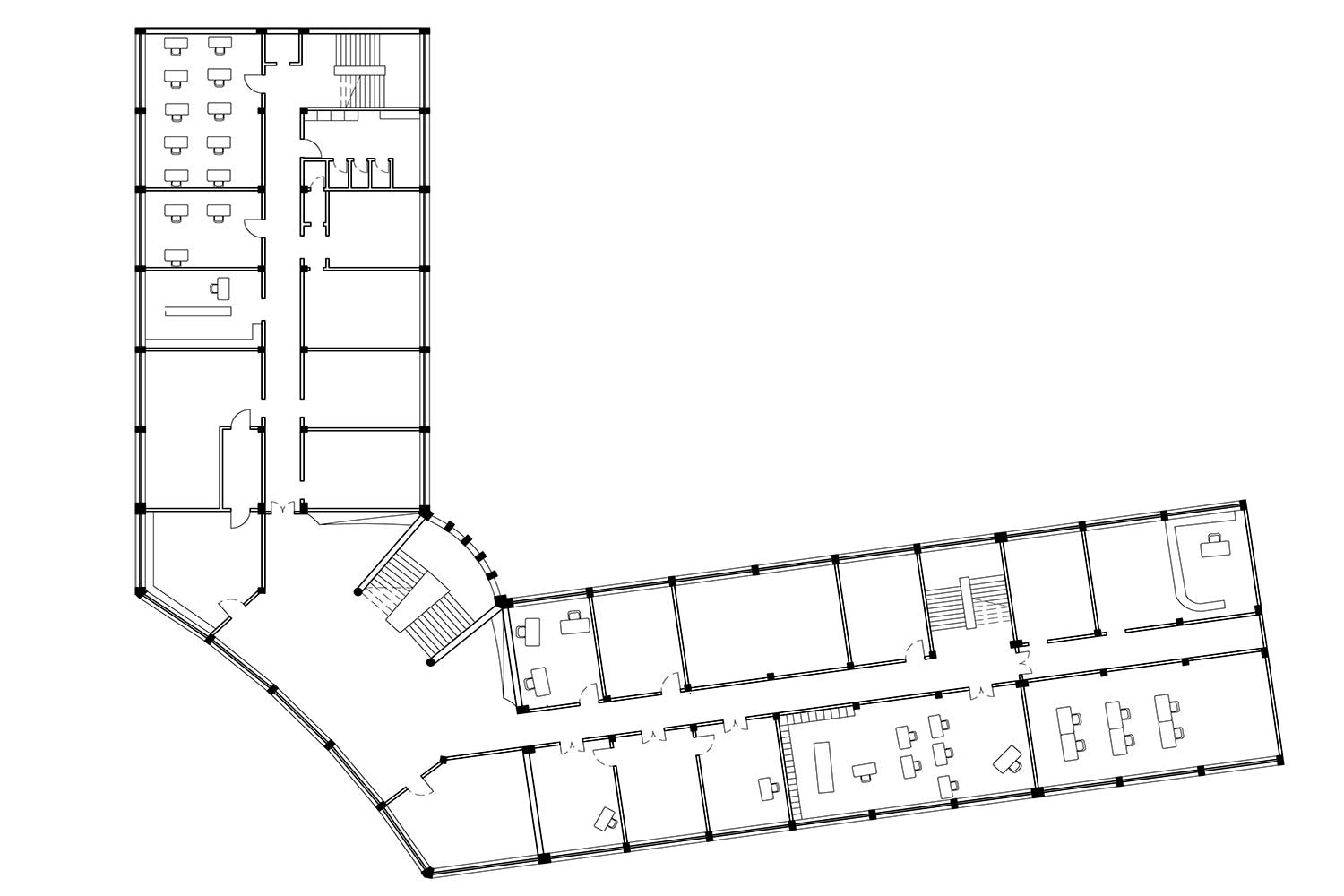

مدارک فنی