موزهی آرامگاه فردوسی، معماری از هوشنگ سیحـــــون، صلابت متواضــع

نوشتهی علی اکبری

Ferdowsi Mausoleum Museum: The Architecture of Humble Solidity Architecture by Hooshang Seyhoun

Ali Akbari

ساختمان موزهی آرامگاه فردوسی که البته در ابتدا به نیت چایخانه و رستوران در دههی ۱۳۴۰ خورشیدی طراحی و ساخته شده است، از آن دست بناهایی است که به خوبی، طراحش یعنی هوشنگ سیحون را نمایندگی میکند. زبان معماری سیحون را میتوان در صفت «صلابت» منتزع کرد. مصالح، تناسبات، هندسه و خطوط قائم و مورب در راستای خلق وقار، شکوه، قوام، پایداری و استواری در پروژههایی که این صفات را میطلبد، هنرمندانه در ذهن و دست سیحون به استخدام درمیآید. از اینرو میتوان به مفهوم «زبان معماری سیحون» قائل بود و نظام نشانهای آن را بازشناخت.

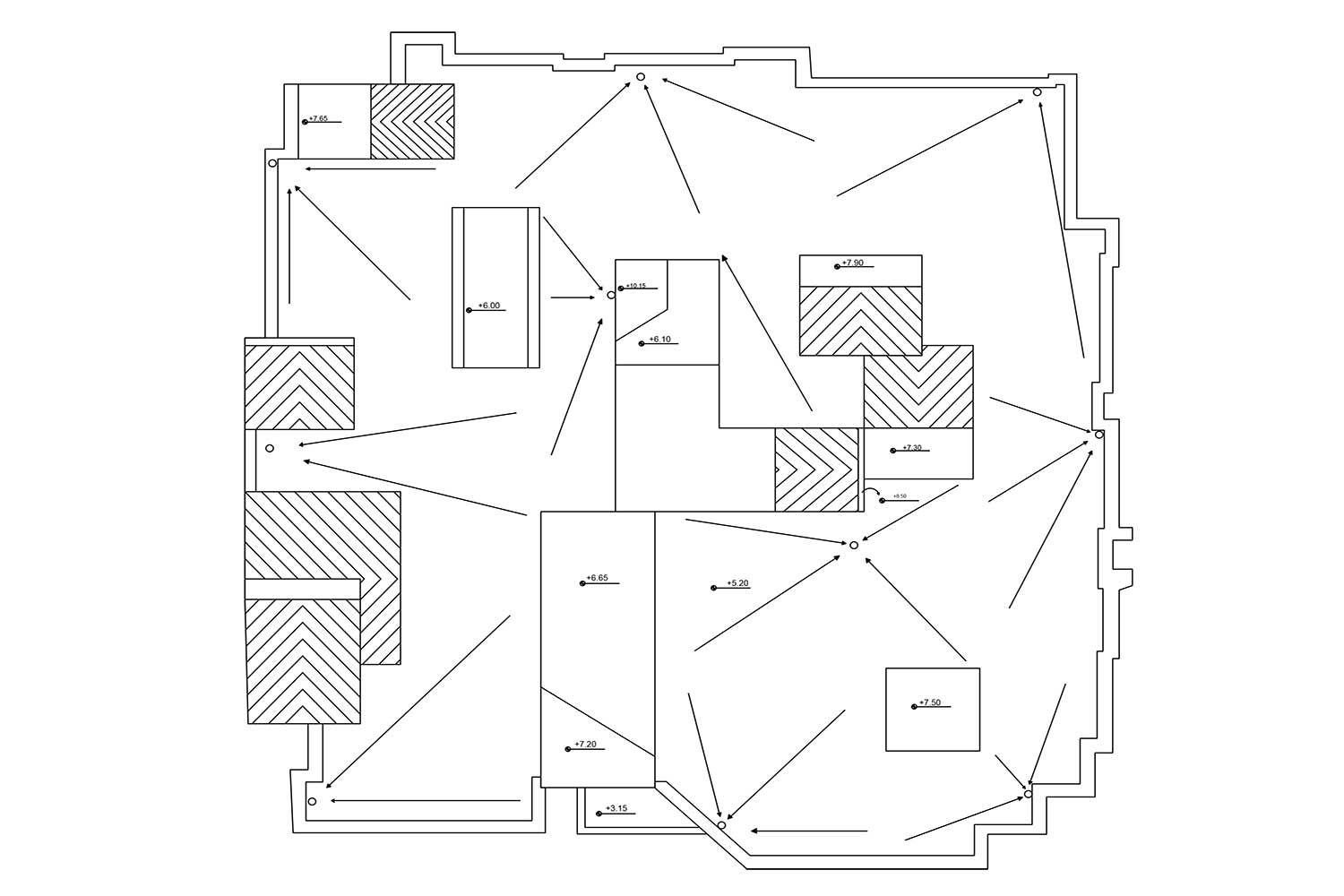

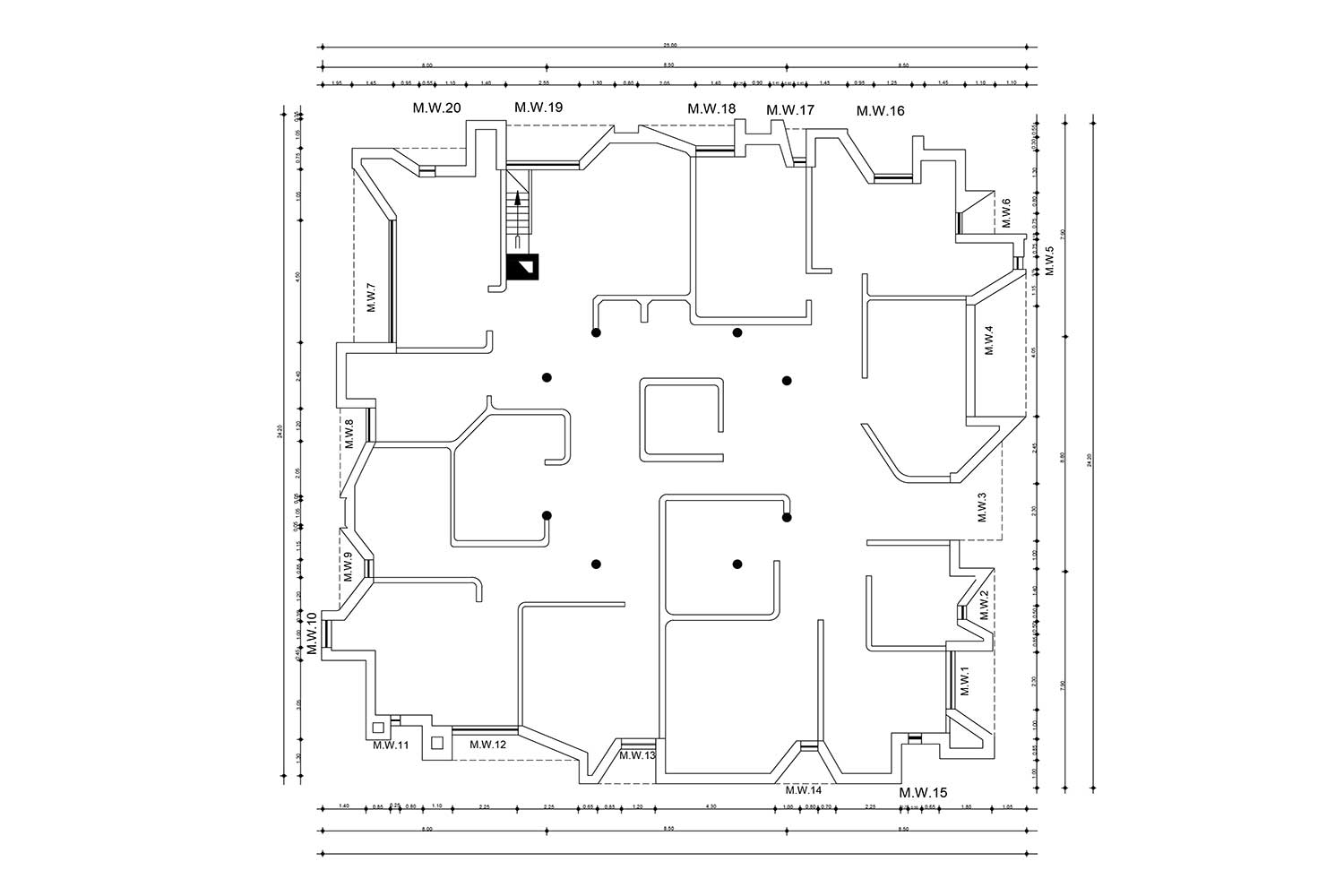

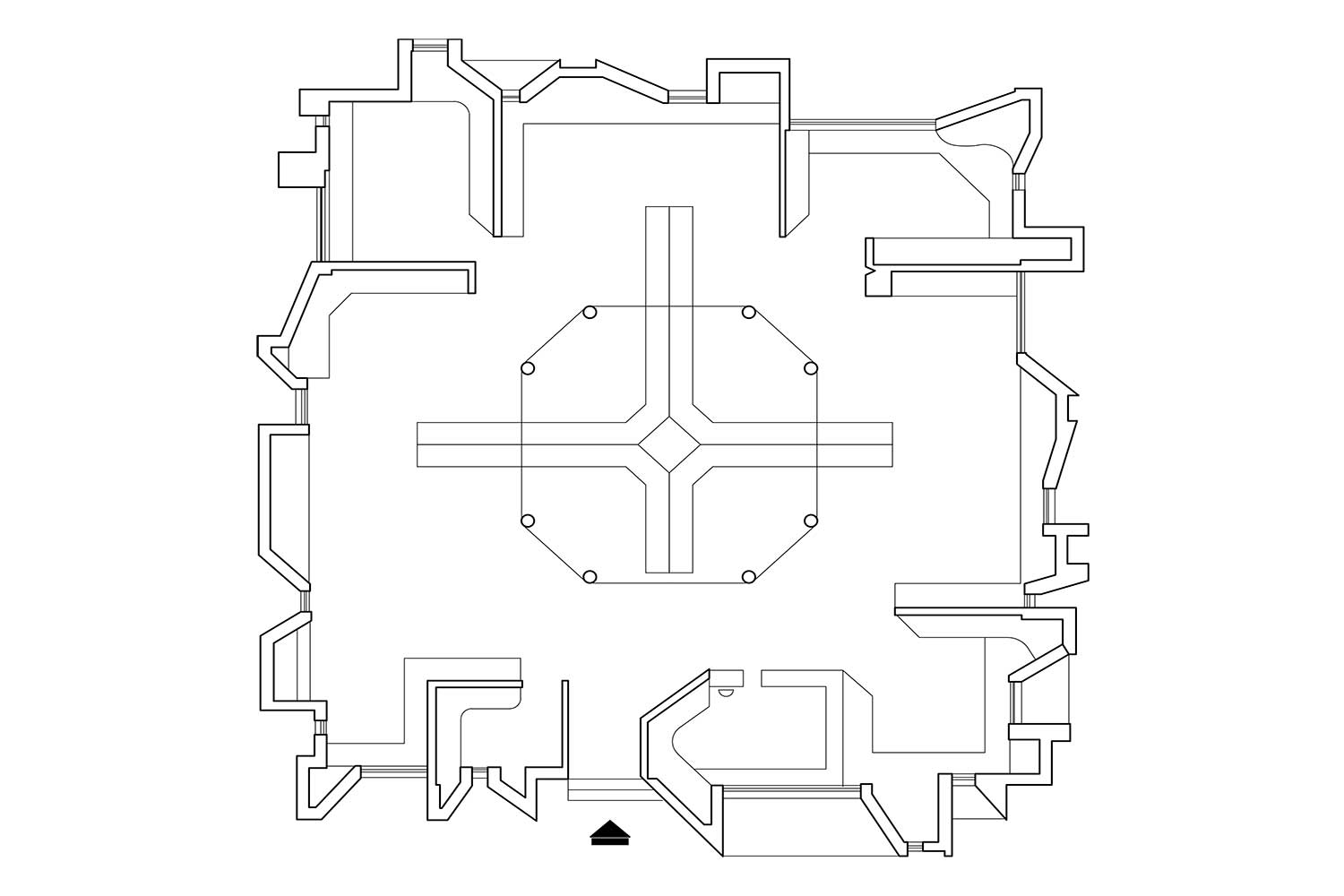

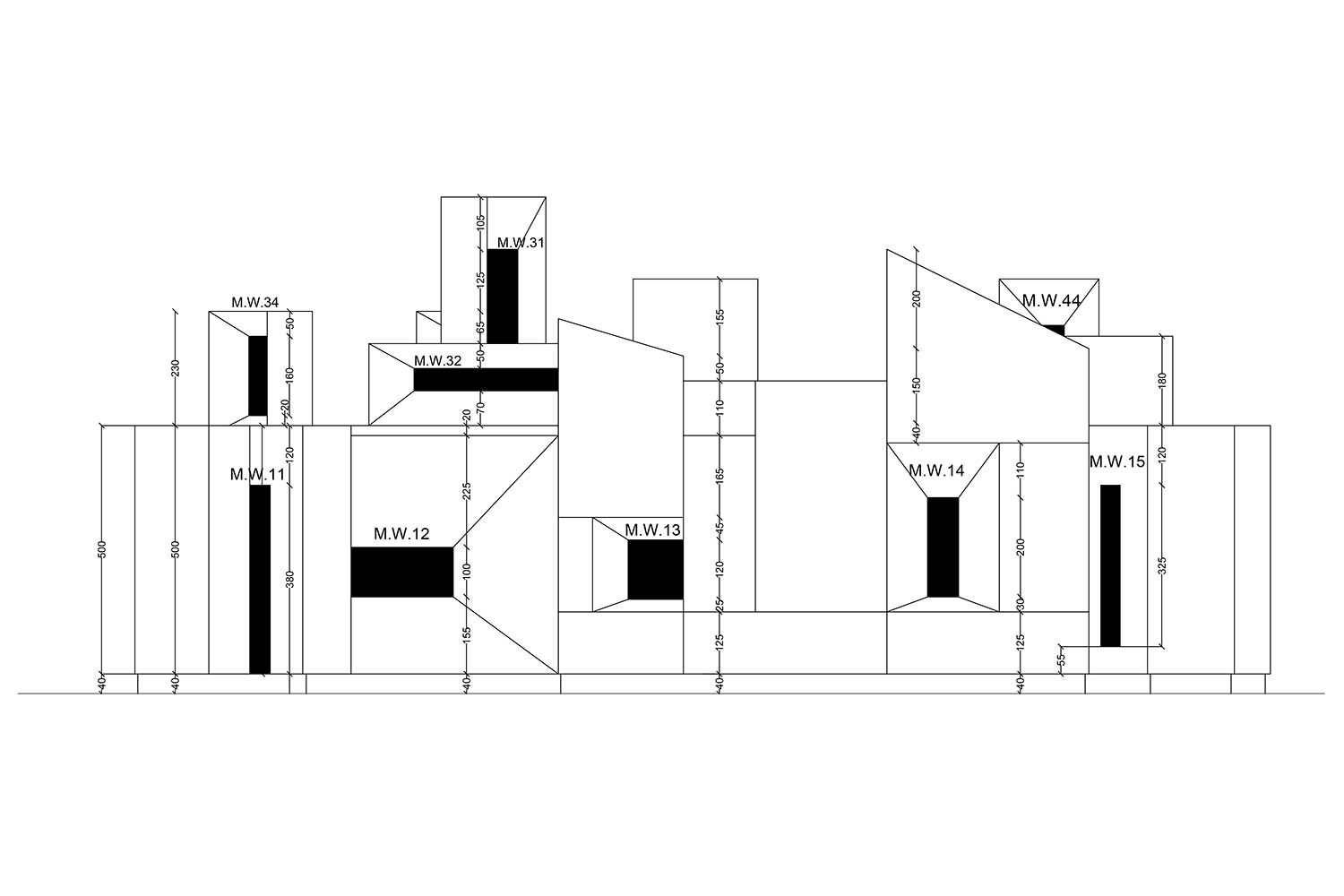

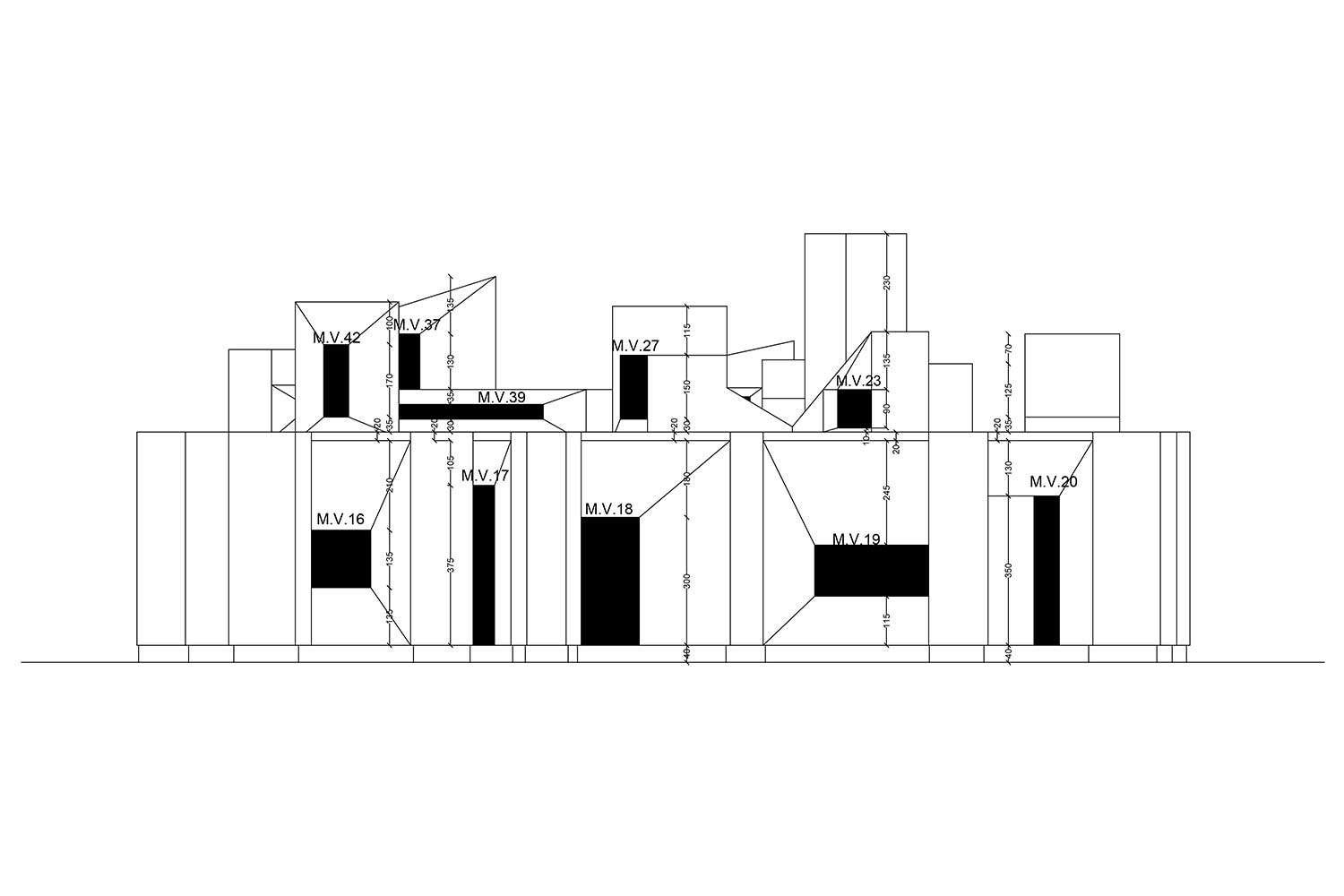

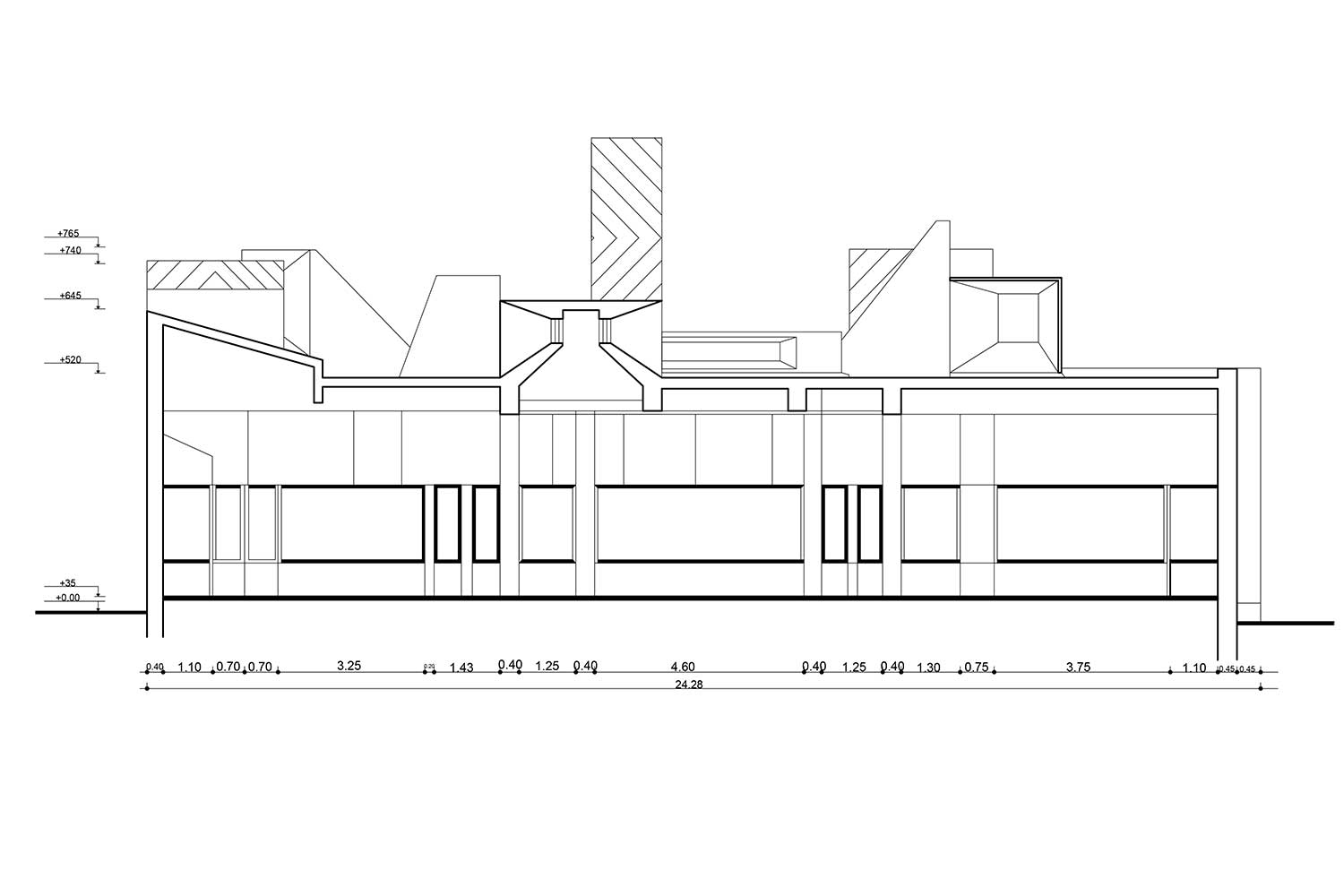

در تحلیل ساختمان موزهی آرامگاه فردوسی و احصای مولفههای منحصربهفرد آن باید تبیین کرد که بنا ضمن آنکه باصلابت است، همزمان توانسته خضوع خود در برابر آرامگاه فردوسی را حفظ کند. تظاهر بتنی بیرون، مستحکم و باوقار است و ارتفاع کمِ ساختمان، فروتنی آن را بهخوبی نشان میدهد. بنابراین، بنا بهخوبی در زمینهی خود نشسته و عالم صغیری در برابر عالم کبیر فردوسی ساخته است. میدانیم گه در گفتمان سیحون، تزئین به معنای هر آنچه بیش از حدنیاز مذموم است و در این بنا نیز حتیالامکان از آن پرهیز شده است. شیشهها به حداقل ممکن رسیده است و از این رو، جهان درون خود را فاش نمیکند و مخاطب را به درون میطلبد. نوعی اسرارآمیزی در ساختمان بهوجود آمده تا کنجکاوی مخاطب را برای کشف و تجربهی درون، تحریک کند. هرچقدر هندسهی بصری آرامگاه بهدلیل تقارن آن، قابل پیشبینی است، در ساختمان موزه، سیحون تلاش کرده است تا با ایجاد تنوع و تفاوت در هر جزء از ساختمان، اعم از هندسهی و تناسبات پنجرهها، ارتفاع عناصر عمودی که چیزی شبیه به بادگیر است و عقبنشینی شیشهها از لبهی بنا، آن را غیر قابل پیشبینی کند. از این حیث، پروژه در زمینهی زمانی-مکانی خود نوعی مدرنیسم آوانگارد در عبور از تقارن، تکثر اجزا در عین وحدت در متریال، غیر قابل حدس بودن برنامهی فضایی و بازتولید عناصر تاریخی آشنا در ضمیر ناخودآگاه ایرانیان را ارائه کرده است. در اینجا، سیحون از طرح آرامگاه بوعلی در همدان که یک بنای تاریخی را بهوضوح بازتولید بتنی کرده بود، فاصله گرفته و به سمت نوعی برداشت استعاری از عناصر تاریخی گام برداشته است که میتواند سرآغاز این نوع معماری در این سده محسوب شود که در آثار دیگران نیز تکرار شد. بنابراین، تجربهی موزهی آرامگاه فردوسی، نقطه عطف تاثیرگذاری در این زمینه محسوب میشود.

قابل فهم است که تکرنگ بودن ساختمان برای بنایی که در جوار آرامگاه فردوسی ساخته میشود و باید در برابر آن، کمترین میزان خودنمایی را داشته باشد، طبیعیترین تصمیم است، آن هم در اندیشهی معماری که سادگی و مینیمالیسم را در آثار خود، مزیت آنها میداند. پس پروژه همزمان که زمینه را پاس میدارد، به زبان تاریخی و بینالمللی توامان سخن میگوید و از این حیث، از متن خود فراتر میرود. باید اذعان کرد که به نظر میآید طراحی این ساختمان، بیش از آنکه ناشی از مسئلهی معمار در پاسخدهی به نیازهای برنامه باشد، محصول نوعی تجربهی جدید برای معمار بوده که خود را به آزمون برده است تا ببیند چقدر میتواند در خلق نوعی معماری مدرن زمینهگرایی موفق باشد که میخواهد از چارچوب مدرن، ولو خیلی اندک و با احتیاط، خارج شود. پس پروژه در خود، مسئلهمحور نیست اما به دنبال پاسخ به مسئلهی کلانتری است و آن تولید زبان جدیدی از معماری است.

بهزعم نگارنده، پروژه توانسته زبانی بیافریند که در پروژههای دیگر و حتی توسط دیگر معماران، بهکار گرفته شود. خیلی زود در دههی ۱۳۵۰ خورشیدی بازتولید عناصر تاریخی معماری ایران بهصورت نمادین و نشانهای، متداول شد و بسیاری کوشیدند چنین زبانی را تجربه کنند. زبانی که توانست از کاربرد مستقیم نشانهها، فرمها و عناصر تاریخی که در معماری پهلوی اول متداول شده بود، فاصله بگیرد و خود را به زبان معماری مدرن نزدیک کند و یا در قالب آن، بازتعریف نماید. بنابراین، پروژه در خلق زبانِ زایا، موفق است.

از حیث مضمون یا محتوای طراحی، به نظر میآید آنچه بهمثابهی درونمایهی اصلی پروژه منظور شده است، همان بیان بصری فروتنانه همراه با اقتدار و صلابت بیرونی است و فضاهای درونی روایت یا سناریویی را بازگو نمیکنند. باید توجه داشت که ساختمان از ابتدا بهعنوان چایخانه و مکانی برای اجرای نقالی و شاهنامهخوانی طراحی و ساخته شده و بعدها به موزه تبدیل شده است. پس بدیهی است که عملکرد فعلی ساختمان با طراحی آن حداقل آنطور که معمار اندیشیده، تناسب ندارد و دستکم روایتهای معمارانهی آن، قابلبازخوانی نیست. هرچند ساختمان توانسته بار موزه را بهخوبی به دوش بکشد اما تحلیل محتوای فضایی آن بهدرستی امکانپذیر نیست.

در مواجهه با ساختمان، بارزترین مشخصهای که منجر به برانگیختن احساسات مخاطب میشود، پرهیز از یکسانی در اجزای بناست و مخاطب را وامیدارد تا دور تا دور پروژه را بپیماید و هر آینه، نمای متفاوتی از ساختمان را پیش چشم خود ببیند. خشونت کنترلشدهی بتن، عظمت، گزندناپذیری، پایداری و استقامتِ شاهنامه طی زمان و جایگاه والای فردوسی در حفظ زبان فارسی و فرهنگ ایرانی را بهنحوی به مخاطب القا میکند که ضمن فراخواندن احترام مخاطب در عین حال از انسانها فاصله نمیگیرد و خود را از آنان دور نمیکند. بنابراین ساختمان توانسته صلابتی متواضع را محقق سازد. باید متذکر شد که فضاهای داخلی دستکم در کیفیتی که امروز تجربه میشود، احساس برانگیز نیست و بنا نمیتواند گفت و گوی قابلتوجهی با انسانهایی ایجاد کند که در آن حضور دارند. بنابراین میتوان گفت فضا به نفع فرم یعنی همهی عناصر و اجزایی که در ساختار همنشینی خاص خود، صورت بیرونی بنا را ساختهاند، کنار کشیده است. معمولا در باب کیفیت فضایی چنین پروژههایی گفته میشود که بنا سکوت کرده است تا رویداد مد نظر که در اینجا اجرای نقالی بوده است، نوای خود را به خوبی و به کمال به گوش مخاطب برساند، اما بهنظر میآید در این اثر، کیفیت فضای داخلی ماهیت خود را از دست داده است. پس شخصیتیافتگی فضاهای داخلی بهمثابهی یکی از مؤلفههای مورد تحلیل در بنا، عنصر مفقودهی بنا به حساب میآید.

هر چند در طراحی تلاش شده است تا با تنوع در پنجرهها، نور و سایه روی بتن عریان و سرد دیوارها، موقعیت فضایی خاصی ایجاد کند اما با توجه به عدمانطباق سطوح نورگیر با برنامهی عملکردی، کیفیت مطلوب و نابی خلق نشده است. احتمالا همین کیفیت سرد و بیروح باعث شده است تا بعدها تصمیم بگیرند که با دیوارهای آجری روی نما و فضای داخلی، سطوح بتنی را بپوشانند تا بلکه فضا کمی گرمتر شود اما لایهی آجری اجرا شده بهقدری نسبت به بنا بیگانه بوده است که چندی بعد تصمیم گرفته میشود دیوارهای آجری، سفید رنگ شود تا چندان به چشم نیاید. باید افزود که شاید بهدلیل خنثی بودن فضای داخلی بوده است که متصدیان امر در دههی ۱۳۶۰ خورشیدی به فکر تغییر کاربری ساختمان و تبدیل آن به موزه افتادند.

عکاس: حسین برازنده، زمستان 1393

Ferdowsi Mausoleum Museum: The Architecture of Humble Solidity Architecture by Hooshang Seyhoun

The building of the Ferdowsi Mausoleum Museum, which was originally designed and constructed in the 1960s as a teahouse and restaurant, is among those rare works that truly and fully represent its architect, Hooshang Seyhoun.

The architectural language of Seyhoun can be distilled into a single, powerful word: solidity.

Materials, proportions, geometry, and the interplay of vertical and oblique lines — all are orchestrated by Seyhoun’s artistic hand and mind to evoke dignity, grandeur, and endurance wherever the project calls for such qualities. Thus, one may justifiably speak of a “Seyhounian architectural language” and identify its distinct semiotic system. In analyzing the museum building and defining its unique characteristics, one must note that while the structure is imbued with firmness, it simultaneously preserves its humility before the tomb of Ferdowsi. The exterior concrete expression is strong and dignified, while the building’s low height conveys a sense of modesty. It settles harmoniously into its context, forming a microcosm before the macrocosm of Ferdowsi’s monumental tomb. Within Seyhoun’s discourse, ornamentation — understood as anything beyond necessity — is deemed undesirable, and here too, such superfluities are consciously avoided. Glass openings are kept to a minimum, ensuring that the interior world remains concealed, inviting the viewer inward. A sense of mystery permeates the building, awakening curiosity and urging exploration. While the tomb’s geometry, grounded in symmetry, is predictable, Seyhoun deliberately makes the museum unpredictable. Each component — window geometry and proportion, the varying heights of vertical elements resembling windcatchers, the recession of glass from the façade’s edge — differs subtly, creating diversity within unity. In this sense, the project, within its temporal and spatial context, presents an avant-garde modernism that departs from symmetry, embraces multiplicity of parts, and reinterprets familiar historical forms embedded in the Iranian collective unconscious. Here, Seyhoun moves away from his earlier literal reconstruction of a historical form — as seen in the concrete reimagining of Avicenna’s Mausoleum in Hamedan — toward a metaphorical reading of historical elements. This marks the beginning of a new architectural tendency in Iran, one that others later echoed. Thus, the Ferdowsi Museum project stands as a pivotal turning point in this evolution. It is understandable that the building’s monochrome appearance is the most natural decision for a structure adjacent to Ferdowsi’s tomb — a building that must display the least possible degree of self-assertion. For an architect who valued simplicity and minimalism as virtues, this approach was only fitting. The project, therefore, respects its context while simultaneously speaking in both a historical and international language, transcending its local frame. It appears that the design of this building arose less from a programmatic necessity than from Seyhoun’s desire to test new architectural possibilities — to explore how far one might go in crafting a modern yet contextually rooted architecture that cautiously steps beyond the rigid modernist frame. The project, then, is not problem-oriented in the narrow sense, but it addresses a larger architectural question: the creation of a new architectural language. In the author’s view, the project succeeded in establishing such a language — one that would soon be adopted and expanded upon by other architects. By the 1970s, the symbolic and semiotic reinterpretation of historical Iranian architectural elements had become commonplace, as many sought to experiment with this mode of expression. This new language distanced itself from the direct imitation of forms and motifs typical of Pahlavi I architecture, instead approaching — and reinterpreting within — the vocabulary of modernism. Thus, the project achieved success in creating a generative architectural idiom. In terms of conceptual content, the core of the design lies in its visual modesty paired with external strength and authority. The interior spaces, however, do not narrate a particular story or spatial scenario. It must be remembered that the building was originally designed as a teahouse and performance venue for storytelling and Shahnameh recitations, later converted into a museum. Hence, the current function only partially corresponds to the architect’s original intent. While the building performs its role as a museum effectively, its spatial narrative is difficult to decipher. The most striking feature of the building — the one that most vividly stirs emotion — is its avoidance of uniformity. This compels the visitor to walk around it, discovering a new façade at every turn. The controlled roughness of exposed concrete, its grandeur and resilience, recall the timeless endurance of the Shahnameh and Ferdowsi’s monumental role in preserving Persian language and culture. The structure commands respect without alienating or distancing itself from the human scale — embodying a kind of humble majesty. Yet, the interior spaces, at least as experienced today, fail to evoke deep emotion or meaningful dialogue with their occupants. The spatial quality seems subdued in favor of form — of the elements and compositions that define the building’s external expression. It is often said that in such projects, the building “falls silent” to let the intended event — here, the Naqqāli storytelling — speak instead. But in this case, it seems the interior has lost its voice altogether. Thus, the personification of interior space, as one of the analytical criteria of architectural character, appears to be the building’s missing element. Although the design attempts to create spatial richness through varied window shapes and the play of light and shadow on cold concrete surfaces, the misalignment between lighting elements and functional program prevents the emergence of a truly refined spatial atmosphere. This cold, inanimate quality likely led to later decisions to cover the concrete surfaces with brick — first on the façade and then inside — to add warmth. However, the new brick layer felt so alien to the original concept that it was soon painted white to reduce its visual impact.

Perhaps due to the neutrality of its interior spaces, by the 1980s the authorities decided to change the building’s function and turn it into a museum.

In summary, the Ferdowsi Mausoleum Museum stands as a bridge between humility and grandeur, a transitional work in Seyhoun’s architectural journey, and a prototype of modern contextualism in Iranian architecture — a structure that, in its silence, continues to speak eloquently of strength, endurance, and respect.

عکاس: حسین برازنده، زمستان 1393

عکاس: شهریار خانیزاد