پیتـر دی.آیزنمــن

Peter David Eisenman

برای همهی علاقهمندان به معماری، دنبال کردن ردی در مسیر معماری که خود بیش از چهل سال به بررسی، جستوجو و مطالعهی دقیق ردهایی از پیشینیان پرداخته و همواره مشغول ساختن، نوشتن و تدریس بوده، امری مهم مینماید و به منظور درک مقصود این هنرمند باید به عقب برویم تا پیشرفت کنیم و ردپای خلا و فقدان را دنبال کنیم تا به وجود برسیم.

بی شک، پیتر آیزنمن یکی از تاثیرگذارترین چهرههای معماری پستمدرن میباشد که میتوان گفت تمامی مسائل معماری جدید یا با ایدهها و فلسفهی او شکل گرفتهاند یا وی به نوعی در آنها دخیل بوده است، شاید این به دلیل حرکت بیوقفهی وی به درون و کنه ایدهها بوده است، همانطور که خود در این مورد میگوید: «من تمام کننده نیستم، من شروع کنندهام و همواره به این فکر میکنم که پروژهی بعدی چه خواهد بود.»

گرِگ لین در مقالهای تحت عنوان آقای ردیاب بااستعداد (The Talented Mr. Tracer)، آیزنمن را بهعنوان یکی از بزرگ ترین نابودگران و بتشکنان معماری معاصر میداند. پسری که بر زمین پدرانش میتازد، غافل از اینکه خود روزی به یکی از آنها بدل خواهد شد. البته در این بین، قطعا، کسانی هستند که همواره سعی بر بزرگداشت و زنده نگه داشتن اجساد مردگان دارند ــ بزرگانی که به چشم کسی چون آیزنمن هبوط ارواحی بیش نیستند. در واقع نبوغ آیزنمن در این است که بیننده را وادار میکند تا رد جنایتکارانی مثل خود (یا همان بتشکنان پیش از خود) را در آثارش پیدا کند و به کشف این واقعیت برسد که از مرگ آنان سالیان سال میگذرد. به عقیدهی لین، تنها بدخواهی جنایت افرادی همچون آیزنمن این است که آنها به عمد اجازه میدهند تا معماری تحت این فرض که قربانیان آنان هنوز از اعتبار خاصی برخودارند به فعالیتش ادامه دهد و تنها نشانهی مرگشان در رمزگشایی ردهایی مبهم میباشد. به عبارتی دیگر، آیزنمن در معماری معاصر، همچون ردیابی حرفهای است که رد معماران تاثیرگذار پیش از خود را میگیرد و مانند قاتلی زنجیرهای، قصد جانشان را میکند که در آثارش ردهایی از جنایت خویش را نیز باقی میگذارد تا ببینندهای تیزبین آنها را رمزگشایی کند. از این رو، یکی از دلایلی که درک آثار آیزنمن را مشکل و آنها را دور از ذهن و بسیار پیچیده جلوه میدهد، تلمیحات گستردهی آکادمیک وی به آثار دیگر معماران است.

بنابر توضیحات گرِگ لین، معماران، در کل، دو نوع هستند: دستهی اول، آنانی که برای مخاطبشان پیامی میگذارند و در پی انتقال آن هستند؛ دستهی دوم، کسانی که برای مخاطبشان ردی به جا میگذارند. اگر بخواهیم در اینجا نگاهی مقایسهای داشته باشیم، باید متذکر شویم که مایکل گریوز هم پیش از این، ردی برای مخاطب به جا میگذاشت (مثل پروژهی خانهی هانسلمن ـ Hanselmann House) و جزو دستهی دوم بهشمار میآمد، اما اکنون او دیگر جزو پیامآوران شده است. از طرفی دیگر، برنارد چومی و پیتر آیزنمن همواره جزو ردیابان بودند و مخاطبشان را نیز به همین چالش میطلبیدند. حال ممکن است بپرسید اساسا تفاوت این دو گروه در چیست؟ در واقع تفاوت این دو در انتزاعی بودن و یا قابلیت حفظ تناقضاتشان نیست، زیرا هر دو معمار ذکر شده (آیزنمن و گریوز) به خوبی تناقضات و تضادهای درونی بنا را حفظ و در حرکت متداوم بین انتزاعات و تاریخگرایی بازنمایی می کنند.

در حقیقت تفاوت عمده در این است که نشانهای گریوز در تمامی آثارش یافتنی اند، زیرا بهعنوان یک پوپولیست، اعتقادی به تیزبینی و هوش مخاطبینش ندارد و آنها را انسانهایی فارغ از درک و شعور میداند که محصولی را ساده و بدون چالش فکری میخواهند، او نیز به ناچار لقمه را آماده در اختیارشان قرار میدهد. اما این در مورد آیزنمن صدق نمیکند؛ گویی آیزنمن به ذکاوت مخاطبینش اعتماد دارد و همچون مجرمی میباشد که از دست مخاطبین تیزبینش در حال فرار است، مخاطبینی که به دنبال ردی از او هستند و او با کوچک ترین لغزش به دام میافتد. در اینجا «رد» به معنای علائمی انتزاعی و نامحسوس است که به صورت تلویحی در اثر معماری نمایـان میشوند و لحظاتی را برای مخاطب به وجود میآورند تا بتواند به آن تفکر اصلی و زیرکی به کار رفته در اثر دست یابد و جهت کشف بیشتر به جستوجو در اثر بپردازد. در نتیجه، تفاوت اصلی در نگرش متفاوت این دو معمار دربارهی مخاطبینشان است. گرچه آیزنمن و گریوز برای سالیان متمادی با هم رابطهی دوستی و همکاری داشتند، تنها دلیل مقایسهی این دو معمار آشناییشان نبوده، بلکه وجوه تشابه و تمایزی است که بین آنان بهعنوان دو معمار تاثیرگذار وجود دارد. برای مثال، هر دوی آنها از توجه بیش از حد به ساختوساز، جزئیات و هر امری که توجهشان را به مصالح معطوف کند، اجتناب میکردند؛ یعنی هم آیزنمن و هم گریوز هنگامی که از آجر در پروژههایشان استفاده میکنند، آن را بیشتر بهعنوان یک روکش در نظر دارند تا مصالحی برای حمل بار سازه.

میتوان گفت پافشاری آیزنمن به نشان دادن فرایند ساخت در پروژههای به اتمام رسیدهاش به این دلیل است که وی مشتاق است مخاطبینش را به خوانشی دقیق از آثارش ترغیب کند. گرگ لین، در ادامه شرح میدهد، معمارانی که برای مخاطبینشان پیام و نشانههایی محسوس میگذارند نگران در دام مخاطب افتادن نیستند، زیرا اساسا آنها مخاطبینشان را منفعل و نادان فرض میکنند، در حالی که معمارانی همچون آیزنمن که ردی از خود به جا میگذارند در واقع مشتاقانه میخواهند دستگیر شوند، زیرا به هوش و ذکاوت مخاطبینشان ایمان دارند. البته تفاوت بین این دو گروه به معنای برتری یکی بر دیگری نیست و یا اینکه بگوییم آثار یکی خلاقانهتر از دیگری است. خیر، هر دو گروه میتوانند آثاری اصیل و خلاقانه داشته باشند؛ منتها دسته ی اول، طراح هستند و دستهی دوم، مجرمانی سرخوش! شایان ذکر است که این مجرمان سرخوش، خود اغلب در پی تقلید از فنون گذشتگانند و همچون قاتلین زنجیرهای، همواره دانشآموختگانِ جنایتکاران برجستهی پیشین هستند.

آیزنمن، این نابغهی معماری پستمدرن، در سال 1932، در نیوجرسی آمریکا، متولد شد و با اشتیاق فراوان مطالعات خود را در رشتهی معماری دنبال کرد و لیسانس خود را از دانشگاه کورنل و فوق لیسانس و دکترای خود را از دانشگاه کمبریـج دریافت نمـود و به عضویـت گروه ملقب به «پنج معمار نیویورک» (The New York Five) درآمد. وی که موسس انستیتو مطالعات معماری و شهری در نیویورک (اوایل دههی 80 میلادی) میباشد، در یک دست خود، معماری و در دست دیگر، تئوری های فلسفی و ادبی را حفظ کرده؛ بهطوری که میتوان گفت، تلاش وی برای ایجاد پیوندی عمیق میان فلسفه و معماری بینظیر است. آنچه بدیهی است تسلط وی بر مبانی فلسفی است. آیزنمن با تاثیر از فلاسفهای همچون فردریش نیچه، مارتین هایدگر و ژان بودریار، روان شناسانی چون زیگموند فروید، کارل یونگ و ژاک لاکان و همچنین ساختارگرایانی نظیر نوام چامسکی، جهت انتقال مفاهیم و تئوریهای مهم به معماری پراخته است. در واقع، نگه داشتن این مقوله های گسترده در کنار هم و پیشبرد آنها به موازات یکدیگر، در تخصص او بود و از همین رو، او را بهعنوان یک نظریه پرداز معماری می شناسند.

آیزنمن کسی است که توانست اولین کار شبه دیکانستراکشن تاریخ را ارائه دهد و نهایتا در مسابقهی مرکز هنرهای بصری کلومبوس، در دانشگاه اوهایو حریفان پستمدرنیست تاریخگرای خود را پشت سر بگذارد و پیروز میدان شود. همچنین وی تا به امروز، برندهی مسابقات فراوانی شده و سخنرانیها و نمایشگاههای زیادی را ارائه داده است. البته تا سال های اخیر، تنها تعداد اندکی از طرح های پیتر آیزنمن به مرحله ی اجرا درآمده و بر همین اساس، بیشتر توجهات کارشناسان این حوزه بر ایده های معماری، نظریات، تئوری ها و مقالات او معطوف شده است ــ ایده هایی که مبنای یک معماری مستقل از بافت هستند…

فهرست آثار معماری پیتر دی. آیزنمن

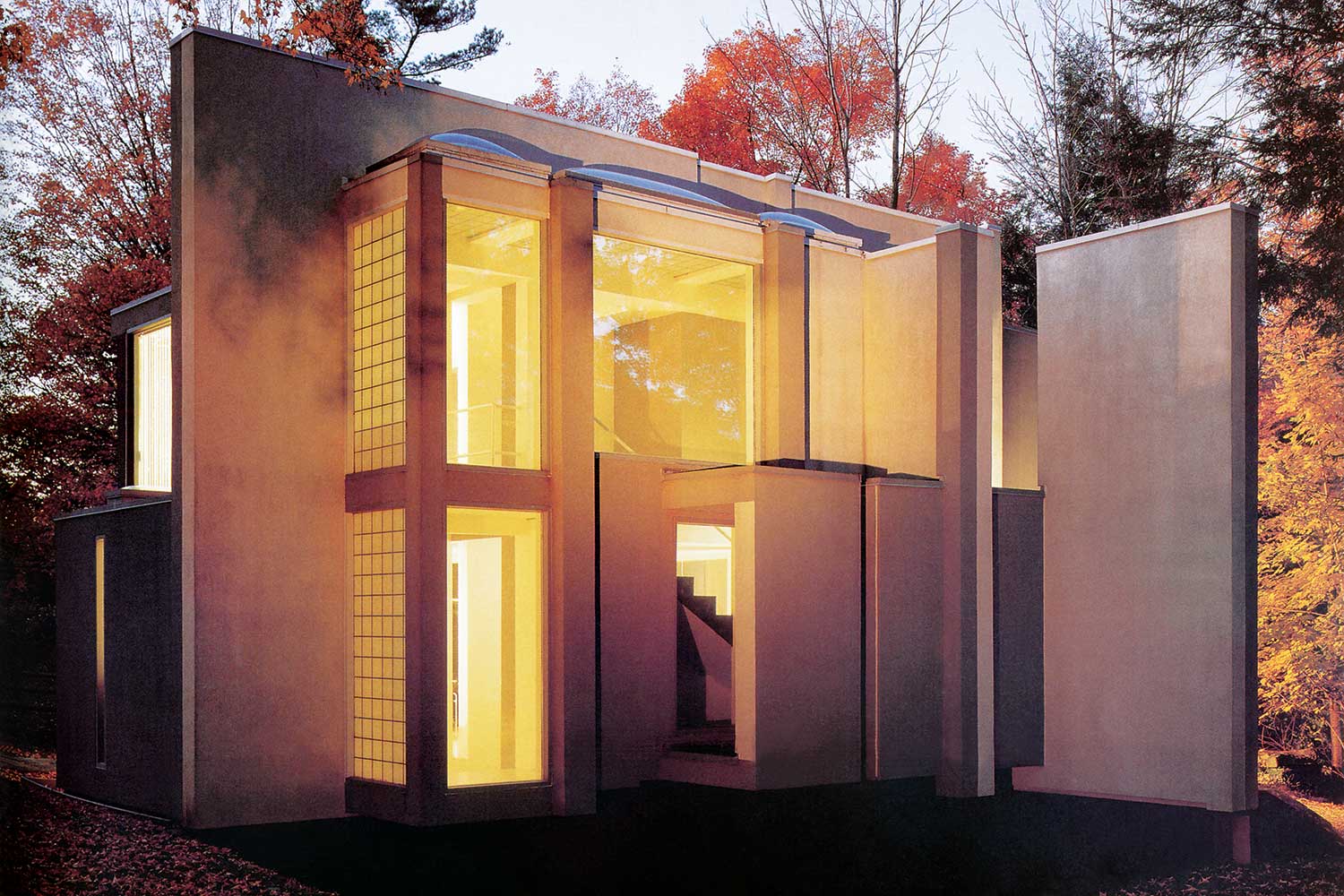

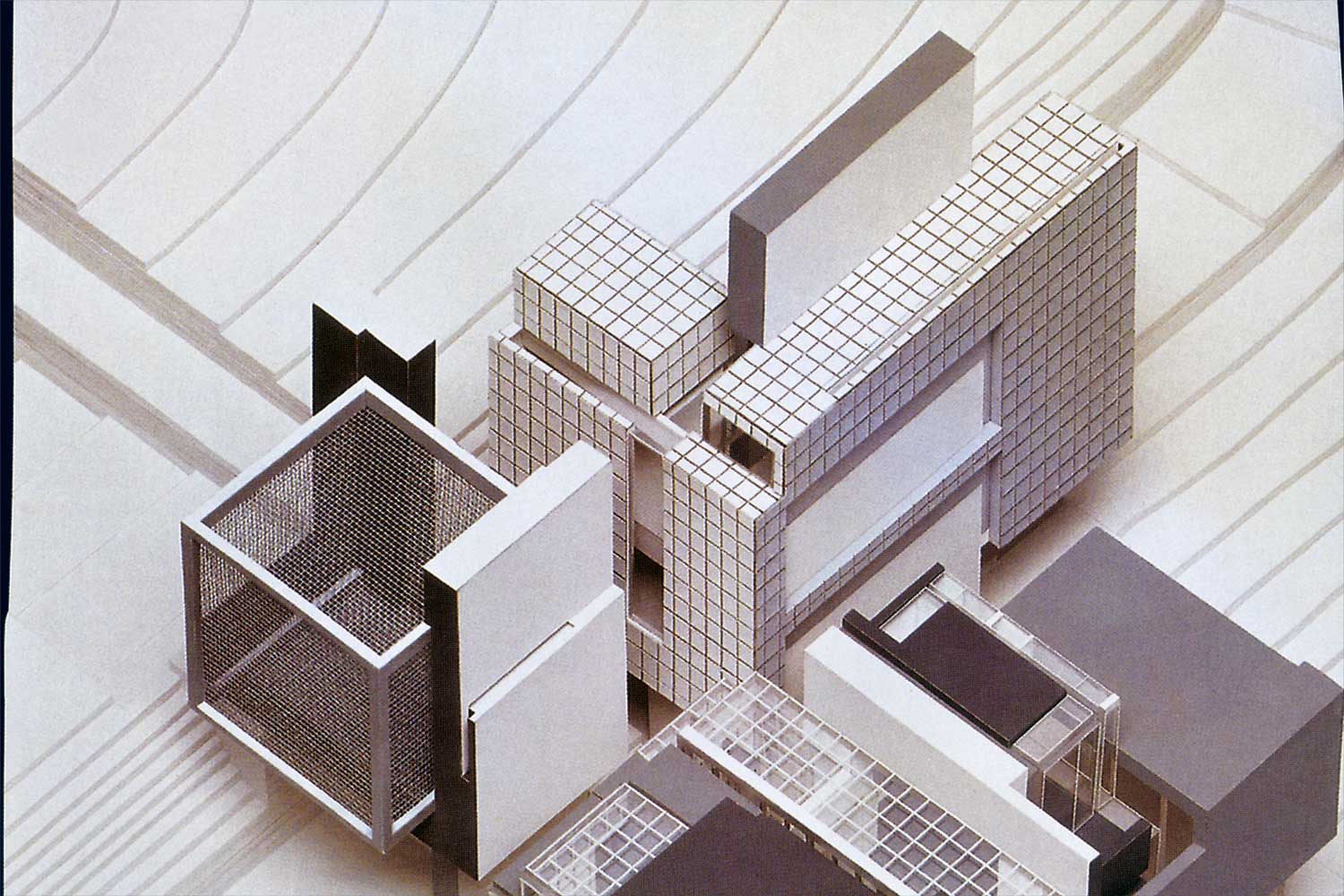

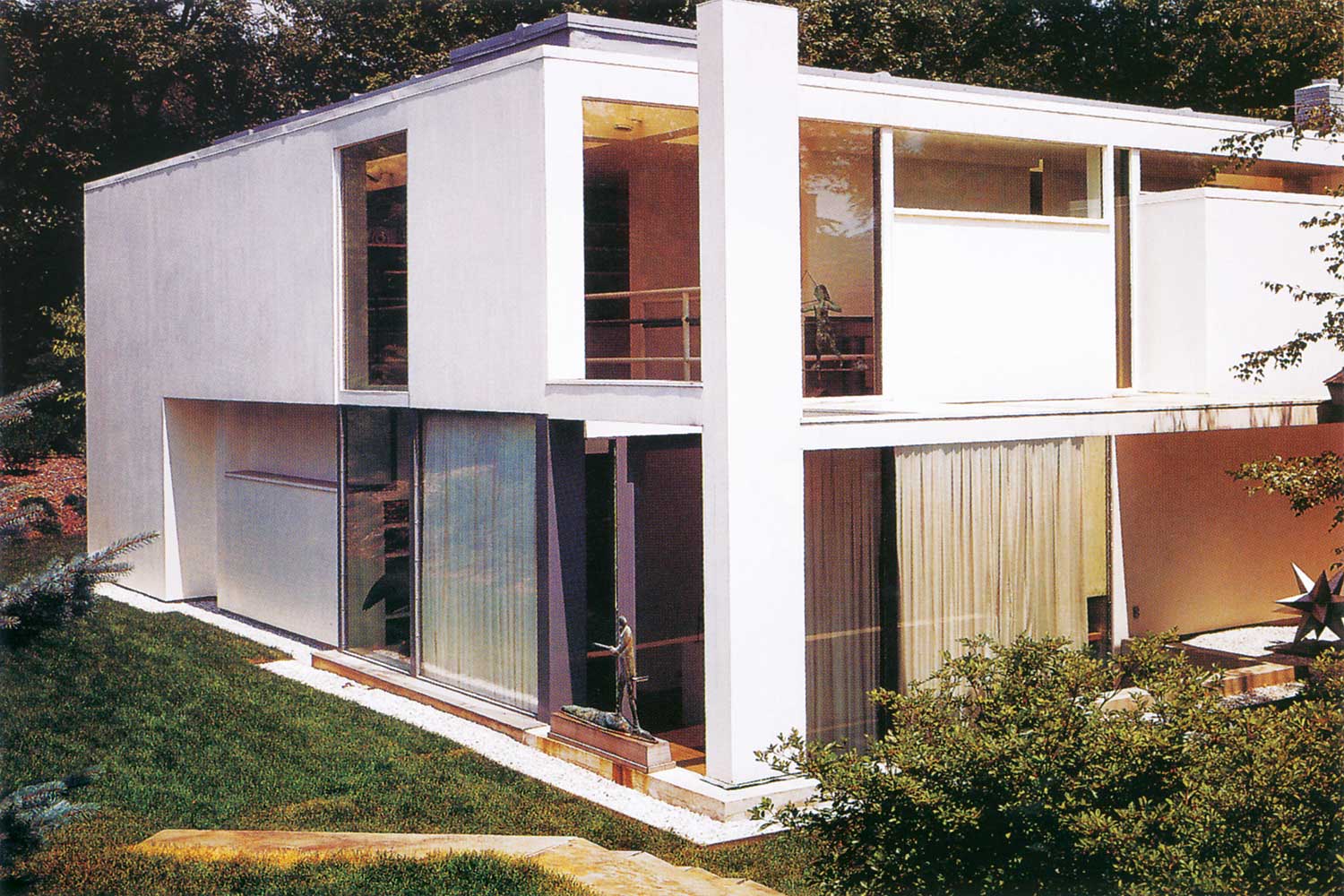

خانههای شمارهدار (House I – X) (۱۹۶۷–۱۹۷۵)

خانهی شماره شش (House VI / Frank Residence)، کورنوال، کانتیکت (۱۹۷۲–۱۹۷۵)

مرکز هنری وکسنر (Wexner Center for the Arts)، دانشگاه ایالتی اوهایو، کلمبوس، اوهایو (۱۹۸۳–۱۹۸۹)

مرکز همایشهای بزرگ کلمبوس (Greater Columbus Convention Center)، اوهایو (۱۹۹۰–۱۹۹۳)

یادبود یهودیان کشتهشدهی اروپا (Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe)، برلین (۱۹۹۸–۲۰۰۵)

شهر فرهنگ گالیسیا (City of Culture of Galicia)، سانتیاگو د کومپوستلا، اسپانیا (۱۹۹۹–۲۰۰۹، ناتمام)

ورزشگاه دانشگاه فینیکس (University of Phoenix Stadium)، آریزونا (۲۰۰۶، با همکاری)

ساختمان مرکزی شرکت کویزومی سانگیو (Koizumi Sangyo Headquarters)، توکیو (۱۹۸۷–۱۹۹۰)

پروژه مسکونی کانارِجو (Cannaregio Housing Project)، ونیز (۱۹۷۸، ساختهنشده)

مرکز طراحی و هنر آرونوف (Aronoff Center for Design and Art)، دانشگاه سینسیناتی، اوهایو (۱۹۸۸–۱۹۹۶)

طرح پیشنهادی پارک لاویلت (Parc de la Villette competition entry)، پاریس (۱۹۸۲–۱۹۸۳، ساختهنشده)

ترمینال فرودگاه بینالمللی سیوداد رئال (Ciudad Real International Airport terminal design)، اسپانیا (ساختهنشده)

بیوسنتر دانشگاه فرانکفورت (Biocenter competition)

ساختمان مرکزی نونوتانی (Nunotani Headquarters Building)، توکیو (۱۹۹۰–۱۹۹۲)

فهرست آثار تألیفی و کتابهای مهم پیتر دی. آیزنمن

خانهی کارتی (1987 – House of Cards )

یادداشتهای دیاگرام (Diagram Diaries – 1999)

ایزنمن از درون به بیرون: نوشتههای منتخب ۱۹۶۳–۱۹۸۸ (Eisenman Inside Out: Selected Writings, 1963–1988) – ۲۰۰۴

ده بنای قانونمند (Ten Canonical Buildings, 1950–2000) – ۲۰۰۸

نوشتهشده در خلأ: گزیده نوشتهها ۱۹۹۰–۲۰۰۴ (Written into the Void: Selected Writings, 1990–2004) – ۲۰۰۷

دیرآمدگی (Lateness) – ۲۰۲۰ (با همکاری الیزا ایتوربه Elisa Iturbe)

مناطق محو شده: پژوهشهایی در میانجی، دفتر ایزنمن ۱۹۸۸–۱۹۹۸ (Blurred Zones: Investigations of the Interstitial, Eisenman Architects 1988–1998) – ۲۰۰۲

پیکانهای متحرک، اروس، و دیگر خطاها: معماری غیاب (Moving Arrows, Eros, and Other Errors: An Architecture of Absence) – ۱۹۸۶

از درون به بیرون: نوشتههای منتخب ایزنمن ۱۹۶۳–۱۹۸۸ (Inside Out: Selected Writings 1963–1988)

مقالات بسیار در نشریات نظری معماری، بهویژه در مجله Oppositions

وبسایت: www.eisenmanarchitects.com

For all those devoted to architecture, tracing the footsteps of one who has himself spent more than four decades in pursuit of traces—searching, examining, and studying with precision the imprints of predecessors—while constantly building, writing, and teaching, is of vital importance. In order to comprehend the intentions of such an artist, one must journey backward to move forward, following the footprints of void and absence in order to arrive at presence. Undoubtedly, Peter Eisenman stands as one of the most influential figures of postmodern architecture. It can be argued that nearly all debates within contemporary architectural discourse have either been shaped by his ideas and philosophies or have been touched by his intellectual presence in one way or another. This may be attributed to his relentless pursuit into the very depths of ideas, as he himself remarks: “I am not a finisher; I am a beginner. I always think about what the next project will be.” In his essay The Talented Mr. Tracer, Greg Lynn identifies Eisenman as one of the greatest iconoclasts and destroyers of contemporary architecture—a son trampling upon the ground of his fathers, oblivious to the fact that he too shall one day become one of them. Meanwhile, there are, of course, those who insist on venerating and preserving the corpses of the dead—masters who, in Eisenman’s eyes, appear as nothing more than fallen spirits. Eisenman’s genius lies in compelling the observer to trace within his works the marks of previous architectural “criminals”—earlier iconoclasts like himself—leading us to the realization that their deaths occurred long ago. According to Lynn, the true malice of these figures lies in their deliberate allowance for architecture to continue under the pretense that its slain forebears retain some lingering authority, when in fact their only surviving trace is hidden in the ambiguous codes left behind. In other words, Eisenman emerges as the consummate tracker within contemporary architecture—hunting down the traces of influential predecessors much like a serial killer—leaving within his own works the very signs of his crimes for the discerning eye to decode. This explains why Eisenman’s architecture so often appears difficult, remote, and intellectually dense: his work is saturated with academic allusions and intertextual references to the oeuvre of other architects.

Lynn distinguishes between two categories of architects: the first, those who leave messages for their audience; the second, those who leave traces. Michael Graves, for example, once belonged to the latter category—his Hanselmann House can be read as such a project—but eventually shifted to the role of a messenger. In contrast, Bernard Tschumi and Peter Eisenman have consistently remained “tracers,” challenging their audience to pursue the latent marks embedded in their work. The difference between these two modes does not lie simply in abstraction or in the ability to sustain contradictions—both Graves and Eisenman masterfully sustain contradictions and oscillate between abstraction and historicist reference. The difference lies instead in their perception of the audience. Graves, as a populist, assumes that his public lacks intellectual acuity; hence his signs are always explicit and easily found, the architectural equivalent of serving a ready-made meal. Eisenman, by contrast, places trust in the intelligence of his audience. He behaves like a fugitive criminal, pursued by his sharp-eyed readers, who are invited to uncover the faintest slip or hidden clue. Here, the “trace” refers to abstract and imperceptible signs that manifest obliquely in architecture—moments through which the attentive observer may glimpse the underlying conceptual rigor and subtlety of the work, prompting deeper inquiry. Although Eisenman and Graves were long-time friends and collaborators, their comparison arises not from personal association but from the structural similarities and divergences in their approaches. Both avoided overemphasis on construction and detail—brick, for instance, was treated not as a load-bearing material but as cladding. Yet Eisenman’s persistence in foregrounding process, even in completed projects, stems from his desire to provoke close readings, forcing audiences into a sustained engagement with the work. Lynn concludes that architects who leave explicit messages for their audience fear no exposure, for they assume passivity and ignorance on the part of their viewers. Architects like Eisenman, however, who leave traces, long to be captured, for they trust in the perceptiveness of their public. The distinction between the two should not be read as a hierarchy—each mode can produce works of authenticity and creativity. The first are designers; the second, joyful criminals. Indeed, these joyful criminals are often heirs to earlier transgressors, mimicking their techniques and perpetuating a lineage of architectural crime.

Eisenman, this prodigy of postmodern architecture, was born in 1932 in Newark, New Jersey. With great fervor, he pursued his studies in architecture, earning his Bachelor’s degree from Cornell University and his Master’s and PhD from the University of Cambridge. He became a member of the celebrated New York Five, and in the early 1980s founded the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in New York. In one hand he carried architecture; in the other, philosophy and literary theory—synthesizing them into a unique intellectual enterprise. His command over philosophical thought is undeniable. Drawing upon Nietzsche, Heidegger, Baudrillard, the psychoanalytic theories of Freud, Jung, Lacan, and the structural linguistics of Noam Chomsky, Eisenman sought to transfer complex philosophical concepts into the domain of architecture. It is this sustained parallel pursuit of philosophy and architecture that has earned him recognition as a true architectural theorist. Eisenman was among the first to offer a proto-deconstructivist project and famously triumphed in the competition for the Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State University, surpassing his postmodern, historicist contemporaries. Over the years he has won numerous competitions, delivered countless lectures, and exhibited widely. Yet, until relatively recently, only a small portion of his projects had been realized. Thus, much of the professional attention directed toward him has centered not on the built fabric but on his architectural ideas, theories, and writings—ideas that form the foundation of an architecture conceived as autonomous from context.