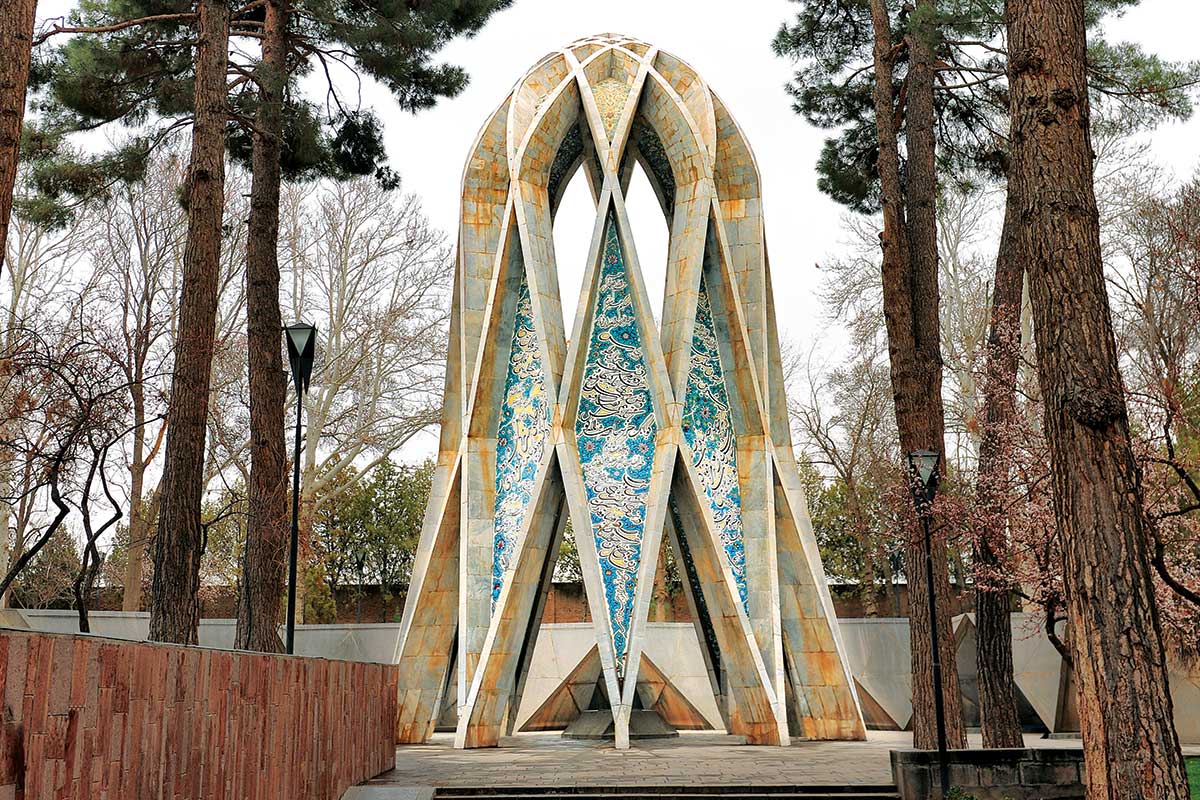

آرامــگاه حکیـم عمـر خیــام اثر هوشنگ سیحون

نوشتهی رکسانا خانـیزاد

The Mausoleum of Ḥakīm ʿUmar Khayyām, Designed by Houshang Seyhoun

به همت انجمـن آثـــار ملـــــی

خواجه امام حجهالحق ابوالفتح عمر بن ابراهیم خیامی نیشابوری معروف به حکیم عمر خیام از ریاضیدانان، حکما و شاعران بزرگ ایران است. قدیمیترین ماخذی که در آنها ذکری از خیام شده غیر از نامهی سنایی به خیام به ترتیب عبارت است از چهارمقالهی نظامی عروضی سمرقندی، مرصادالعباد شیخ نجمالدین ابوبکر رازی معروف به دایه، نزههالارواح و روضهالافراح فی تواریخ حکماءمتقدمین والمتاخرین از شمسالدین محمد بن محمود الشهرزوری، کاملالتواریخ ابن اثیر، تاریخالحکماء قاضی اکرم جمالالدین ابوالحسن علی بن یوسفالقفطی، آثارالبلاد والاخبارالعباد زکریا بن محمد بن محمودالقزوینی، جامعالتواریخ رشیدالدین فضلالله وزیر، فردوسالتواریخ ابرقوهی، تاریخالفی از احمد بن نصرالله تتوی هندی (حواشی چهارمقالهی قزوینی). خیام بین سالهای 230 و 440 دیده به جهان گشود، از دوران جوانی و تحصیلات او اطلاع صحیحی در دست نیست و آنچه مسلم است وی در حکمت، ریاضی، نجوم و پزشکی از سرآمدان روزگار خود بوده است. در سال 467 ه.ق ملکشاه سلجوقی خیام را با چند تن دیگر از دانشمندان بنام آن روزگار چون ابوالمظفر اسفزاری و میمون بن نجیب واسطی و ابوالعباس لوکری به اصلاح تقویم مامور ساخت. نوشتهاند که:«نظریات خیام برای اصلاح تقویم حتی از تقویم فعلی اروپا که موسوم به تقویم گریگوریست صحیحتر است، چه تقویم گریگوری در طول 2320 سال یک روز خطا میکند و تقویم خیام در 3770 سال یک روز خطا میکند.»1خیام با همکاری ابوالفتح عبدالرحمن المنصور الخازنی و دیگر دانشمندان، رصدی برای ملکشاه ترتیب دادند که مال بسیار بر آن خرج شد و تا سال 485 یعنی سال وفات ملکشاه دائر بود و پس از آن متروک شد2.

رسالههایی که در علوم ریاضی از خیام بازمانده همه دلایل بارزی است بر تبحر و استادی خیام در علوم ریاضی. چنانکه اشاره شد خیام در پزشکی نیز از سرآمدان روزگار خود بوده و نوشتهاند که سنجر ملکشاه بیماری آبله داشت و خیام را برای معالجهی او برگماشتند. خیام در روزگار خود نیز مورد احترام پادشاهان، بزرگان و دانشمندان بود و با سلاطین و رجال دورهی سلجوقی چون ملکشاه و خواجه نظامالملک و دانشمندانی چون غزالی مراوده داشته است. اما شهرت فوقالعادهی خیام در قرن اخیر در مشرق و اروپا و آمریکا بیشتر به سبب رباعیات حکمتآمیزی است که از وی بازمانده است. رسالههای خیام در علوم ریاضیات (مانند جبر و مقاله، فی شرح ما اشکل من مصادرات کتاب اقلیدس و نیز حل یک مسئلهی جبری به وسیلهی قطوع مخروطی) دال بر تبحر و استادی وی در این علم است. جورج سارتن، استاد علوم تاریخ در دانشگاه هاروارد آمریکا و از مورخان علوم قرن بیستم در یکی از تالیفات خود تحت عنوان مدخل تاریخ علوم مینویسد:«عمر خیام یکی از بزرگترین ریاضیدانان قرون است. کتاب جبر او حاوی حل هندسی و جبری معادلات درجهی دوم، طبقهبندی قابلتحسین معادلات درجهی اول و دوم و سوم و تحقیق منظم در حل تمام و حل ناتمام اکثر آنهاست… این رساله یکی از برجستهترین آثار قرون وسطایی و احتمالا برجستهترین آنها در این علم است.»

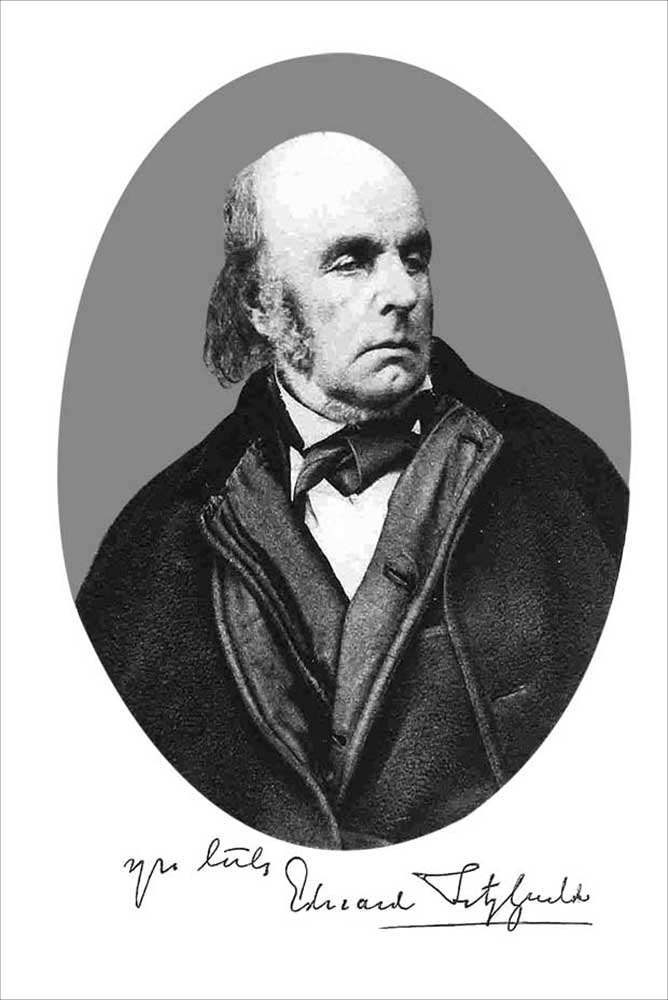

حرفهی خیام شاعری نبود ولی گاه عقاید و نظریاتش را در قالب رباعیاتی حکیمانه بیان میکرد. قسمتی از تالیفات خیام در پی افتوخیزهای تاریخ در طی سالها از بین رفته است. برخلاف گفتههای عوام که خیام را «خراباتی و بادهپرست» میخوانند یا از روی اغراض یا هوس، وی را «مست و بادهخوار» معرفی میکردهاند، در مستندات تاریخی بهکرات ضد این بیان شده و علم و شناخت عمیق خیام را نافی آن ویژگیها میدانند. مرحوم نخجوانی مینویسد:«این اندیشههای لاابالیانه، ایرانیان را به سوی جمود و خمود و سستی و لاابالیگری میکشاند. ما خیام را برای ایران میخواهیم، نه ایران را برای خیام.» حکیم عمر خیام از قرن نوزده به اینطرف در اروپا و آمریکا شهرت یافت و شاید بتوان بدون اغراق او را معروفترین شاعر ایرانی در مغربزمین به شمار آورد. البته آغاز این معروفیت در پی ترجمههای ادوارد فیتز جرالد (انگلستان، 1809) از اشعار خیام به زبان انگلیسی بوده است که از روی نسخهی کتابخانهی بادلیانِ آکسفرد -که تاریخ 865 هجری قمری را بر خود دارد و مشتمل بر 101 رباعی است- در سال 1859 صورت گرفت.

استقبال انگلیسیها از این اشعار، زبان و مضامین آنها چنان بوده است که بسیاری از مردم، قطعات زیادی از آن را به خاطر سپردند، عباراتش زبانزد خاص و عام شد، به مثَلها راه پیدا کرد و کلماتی نظیر «کوزه، ساقی، بلبل، پروین، کاروانسرا، جمشید و بهرام» که فیتزجرالد عینا در ترجمهی خود آورده بود، مانوس انگلیسیزبانان شد.

قدیمیترین ماخذی که از قبر خیام سخن گفته، چهـارمقـالهی نظامی عروضی است، به سال 506 هجری قمری که علاوه بر اطلاعات محل دقیق قبر، در آن نوشته است:«من در میان مجلس عشرت از حجهالحق عمر شنیدم که او گفت:«گور من در موضعی باشد که هر بهاری شمال بر من گلافشان میکند». مرا این سخن مستجیل نمود و دانستم که چونی گزاف نگویی. چون در سنه ثلاثین به نیشابور رسیدم، چهار (چند) سال بود تا آن بزرگ روی در نقاب خاک کشیده بود.» (بحرالعلومی، ۱۳۵۵) پس از درگذشت حکیم عمر خیام جسد آن بزرگ را در گورستان حیرهی نیشابور نزدیک امامزاده محمد محروق به خاک سپردند. با حملهی مغول به نیشابور و کشتار عمومی مردمِ آن شهر، بناها ویران شد و گورستانها نیز خراب و پایمال گردید. پس از آن نخستین بار در زمان سلطان حسین بیقرا بقعهی امامزاده محروق تجدید بنا شد و در زمان شاه طهماسب صفوی ایوان جلوی بقعه و غرفههای اطراف احداث گردید و یکی از آن غرفهها در جهت شرقی بنای امامزاده محل قبر حکیم عمر خیام بود و قبر به صورت مکعب مستطیل با آجر و گچ در وسط غرفه قرار داشت.

همانطور که پیشتر در شمارههای قبلی هنرمعماری شرح دادیم در سال 1313 مراسم جشن هزارهی فردوسی در تهران و توس برگزار گردید و چون پیشبینی میشد که خاورشناسان و دانشمندانی که به توس مسافرت میکنند و طبعا از نیشابور میگذرند به زیارت عمر خیام هم خواهند رفت لذا انجمن آثار ملی بر آن شد که بر مزار او آرامگاهی بنا کند و چون وقت کافی در پیش نبود با شتاب ساختمان سنگی روبازی در محل غرفهی قبر خیام ایجاد شد. طرح جدید این آرامگاه اثر کریم طاهرزاده بهزاد، که در مشرق بارگاه امامزاده محمد محروق در زیر آسمان قرار داشت عبارت بود از دو ایوان بالا و پایین و دیوارهی کوتاه سنگی از سنگ خلج مشهد در اطراف محل قبر، روی قبر که سه چهار متر از دیوار بقعهی امامزاده فاصله داشت ستونی قرار داده شده و این رباعیات از ملکالشعرای بهار بر آن منقوش بود:

بر تربت خیام نشین کام طلب

یک لحظه فراق از غم ایام طلب

تاریخ بنای بقعهاش گر خواهی

کام دل و دین ز قبر خیام طلب

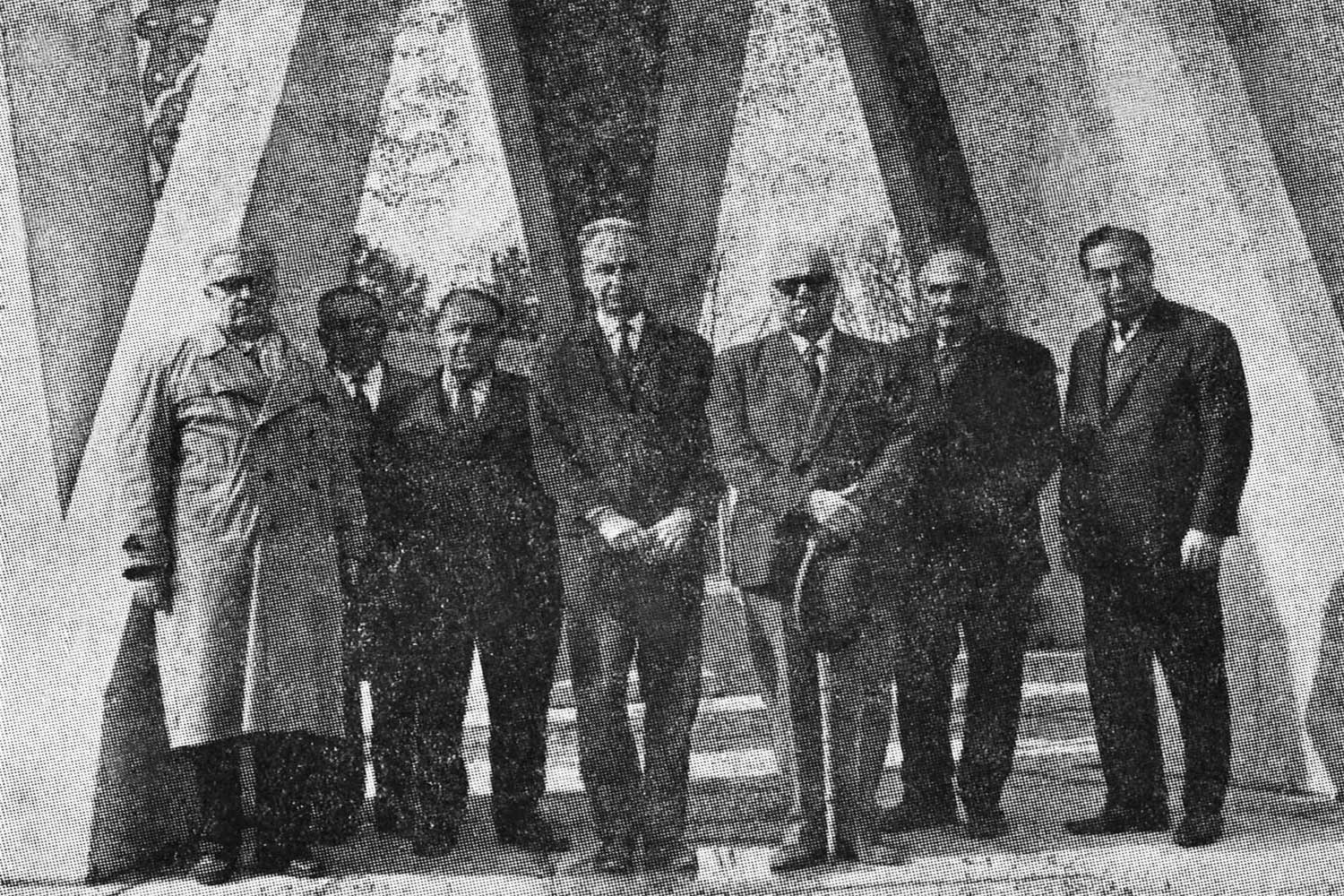

دربارهی این بازدید (بازدید مهمانان هزارهی فردوسی از مقبرهی خیام) آقای دکتر صدیق که خود جزو کاروان بوده نوشتهاند:

«خاورشناسان بهتدریج از راه رسیدند و وارد باغ شدند و از منظرهی دلانگیز و فرحبخش آن شاد گشتند و بر ذوق و هنر ایرانی آفرین گفتند تا به مزار خیام رسیدند و دور آن حلقه زدند. آنان که فارسی میدانستند رباعی مذکور را خواندند و برای سایرین ترجمه کردند. اشتیاق فوقالعادهی خاورشناسان به زیارت خیام آنان را به مراقبه و تامل عمیق واداشت، ناگاه «سر دنیسن راس» که تالیفی دربارهی خیام کرده رباعی ذیل را از ترجمهی انگلیسی فیتز جرالد به آوای بلند از حفظ خواند:

چون میگذرد عمر چه شیرین و چه تلخ

پیمانه چو پر شد چه نشابور و چه بلخ

می نوش که بعد از من و تو ماه بسی

از سلخ به غره آید از غره به بلخ

«درینک واتر» لحظهای بعد، رباعی زیر را از همان ترجمهی فیتز جرالد از بر با آهنگ دلپسند و شیوایی بسیار خواند:

یاران چو به اتفاق میعاد کنید

خود را به جمال یکدیگر شاد کنید

ساقی چو می مغانه بر کف گیرد

بیچاره مرا هم به دعا یاد کنید

از شنیدن این رباعی یکی از مهمانان از شدت شور و اشتیاق به صدای بلند به گریه افتاد و طبعا حضار بدو تاسی جستند و حالی به همه دست داد که من از وصف آن عجز دارم. (بحرالعلومی، ۱۳۵۵)

آرامگاه جدید خیام

از همان سال 1313 که آرامگاه خیام گشایش یافت، علاقهمندان به خیام و مردم صاحبنظر، آن را درخور شان و مقام خیام نمیدانستند و به خصوص پس از آرامگاه ابنسینا و سعدی و شروع به ساخت آرامگاه نادر پیوسته از اولیای امور انجمن آثار ملی میخواستند که بنایی متناسب با مقام خیام بر تربت او بنیاد نهاده شود. آقای فاضلی رئیس فرهنگ نیشابور از سال 1333 با ارسال گزارشها و نامههایی به استاندار خراسان و وزارت فرهنگ و انجمن آثار ملی پیوسته تقاضای مردم و زائران مزار خیام را دربارهی بنای آرامگاه آن بزرگ اظهار میداشت و در تیرماه 1335 آقای رام، استاندار خراسان، از انجمن آثار ملی درخواست کرد که نقشهی آرامگاه خیام و عطار تهیه شود و پس از آن آقای رضا جعفری استاندار و رئیس انجمن آثار ملی خراسان به انجمن آثار ملی نوشت که در سفر نیشابور، آرامگاه خیام بازدید شد، این بنا به هیچ وجه متناسب با شان و مقام آن حکیم نیست و درخواست کرد که برای تجدید بنای آرامگاه خیام که از هر حیث مناسب باشد اقدام و بذل توجه شود. در نامههایی که پس از آن از مقامات اداری و رسمی خراسان و نمایندگان آن استان در مجلس شورای ملی و مجلس سنا به انجمن آثار ملی میرسید درخواست میشد که نقشهی اساسی بنای آرامگاه خیام تهیه و هزینهی ساختمان آن برآورد شود تا مردم خراسان نیز به سهم خود در این امر مهم ملی شرکت جویند.

در آبان ماه سال ۱۳۳۵ انجمن آثار ملی به استاندار خراسان اطلاع داد که از چندی قبل جهت تهیهی نقشهی متناسب برای آرامگاه خیام و بقعهی عطار و آرامگاه کمالالملک اقدام شده و پس از خاتمهی امر نسبت به ارسال آن به استانداری و انجمن آثار ملی خراسان اقدام خواهد شد.

نقشهی بنا

در مرداد ماه ۱۳۳۵ از طرف انجمن آثار ملی به مهندس سیحون استاد دانشگاه تهران نوشته شد که طبق گزارشهای رسیده وضع ساختمان آرامگاه عمر خیام بسیار نامناسب میباشد و انجمن در نظر دارد در این مورد اقداماتی به عمل آورد ، نقشه و طرح لازم را تهیه نموده و با انجمن در این باره همکاری نمایید و در آذر ماه همان سال مجددا از طرف انجمن به مهندس سیحون نوشته شد که چون در نظر است آرامگاهی که با شان حکیم عمر خیام و کماللملک متناسب باشد ساخته شود همانطور که قبلا هم در این باره مذاکره شده نقشهای متناسب و سزاوار مقام آن حکیم بزرگ و این هنرمند شهیر تهیه و به انجمن آثار ملی ارسال دارید تا در این موقع که زمرهی علاقهمندان به انجام این امر به انجمن آثار ملی مراجعه میکنند دربارهی تهیهی مقدمات آن اقدام شود.

یک ماه بعد آقایان مهندس سیحون و حسین جودت پس از بازدید آرامگاه خیام در نیشابور طی گزارشی به اطلاع انجمن رسانیدند که:«…راجع به مقبرهی خیام به طوریکه ملاحظه فرمودهاند، محل آن فعلا چسبیده به بقعهی امامزاده محروق میباشد و هرگونه عملی در این محل نمیتواند استقلال و برجستگی به مقبرهی خیام بدهد و لازم است که محل جدیدی در همان محوطه در نظر گرفته شود. با مطالعاتی که در این قسمت به عمل آمد محل آرامگاه تعیین گردید و کروکیهای لازم نیز متناسب با محل جدید تهیه شد تا در صورتیکه مورد موافقت باشد نقشههای تکمیلی و صورت برآورد هزینهی آن تقدیم گردد.» (بحرالعلومی، ۱۳۵۵)

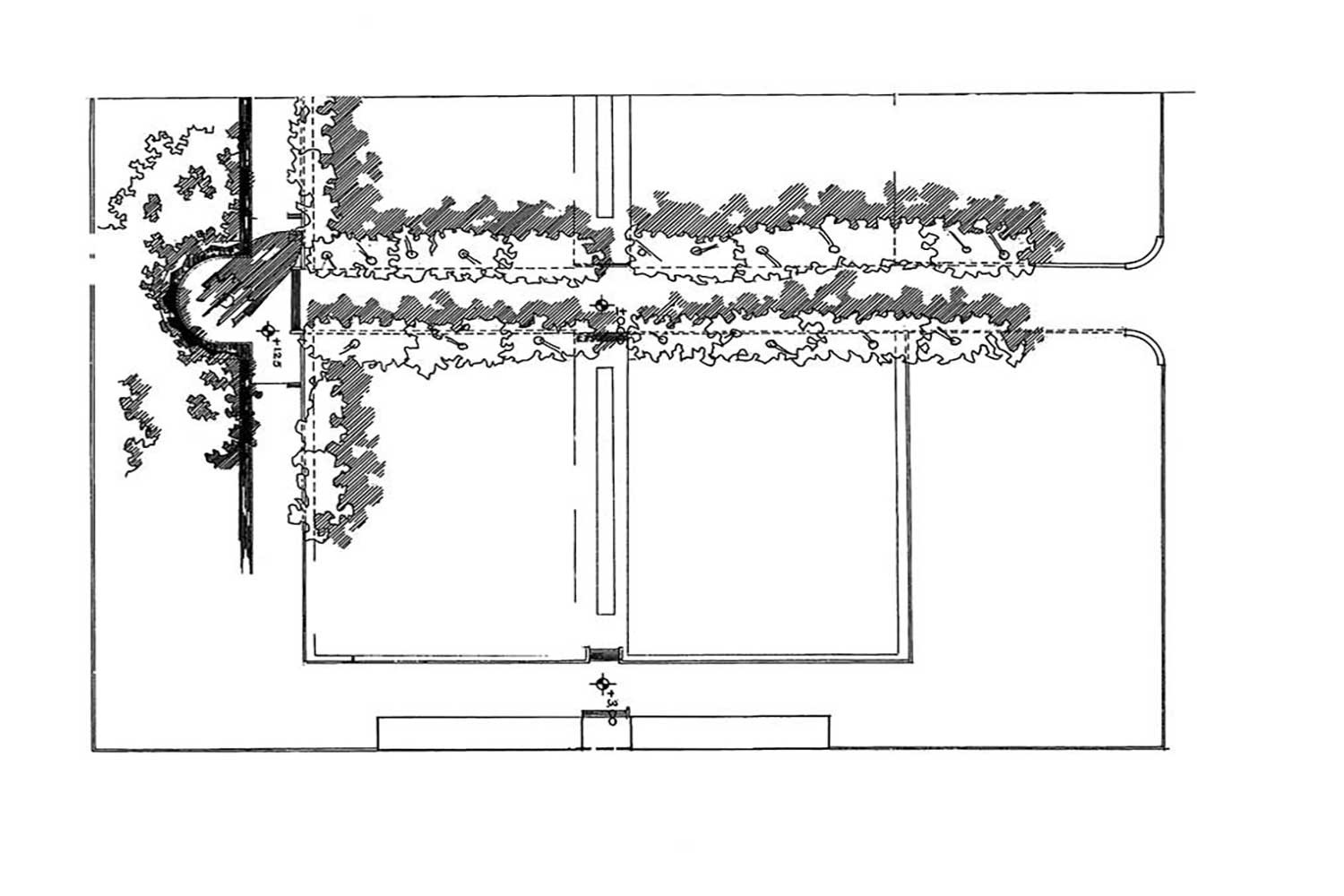

توضیح این نکته لازم مینماید که مساحت باغ امامزاده محمدبن محروق که در زمان صفویه در محل قبرستان حیره احداث شده در حدود 43200 مترمربع است و به صورت مربع مستطیل به طول 240 متر و عرض 180 متر شمالی جنوبی میباشد و بقعهی امامزاده در وسط این باغ قرار دارد و محلی را که مهندس سیحون برای آرامگاه خیام در نظر گرفته بود و آرامگاه خیام در آن محل بنا شد در گوشهی شمال شرقی باغ قرار دارد.

انجمن آثار ملی طرحی را که مهندس سیحون برای آرامگاه خیام تهیه کرده بود، در ششم خردادماه 1337 به دانشکدهی هنرهای زیبای دانشگاه تهران فرستاد و تقاضا کرد که طرح مذکور را مورد مطالعهی دقیق قرار دهند و هرگاه از لحاظ اصول فن معماری ایران نکات و دقایق بیشتری در نظر دارند مراتب را اعلام نمایند تا آقای مهندس سیحون در تکمیل و تهیهی نقشهی قطعی اقدام نماید. آقای مهندس محسن فروغی، رئیس دانشکدهی هنرهای زیبا در تاریخ 17 خردادماه 1337 طی نامهای به انجمن اطلاع داد که طرحی که توسط آقای مهندس هوشنگ سیحون استاد این دانشکده برای آرامگاه حکیم عمر خیام تهیه شده است و ماکتهای مربوط به آن مورد دقت قرار گرفت و از طرف آقای مهندس سیحون دربارهی آن توضیحات کافی داده شد. با توجه به این نکته که در تهیهی طرح مزبور از سبک معماری ایران حداکثر استفاده به عمل آمده این نقشه چه از لحاظ اصول فن معماری و چه از نظر سبک برای آرامگاه حکیم بزرگ ایران کاملا متناسب است.

از آن پس اعضای انجمن آثار ملی در جلسههای متعددی موضوع بنای آرامگاه و نقشهی آن را مورد بررسی دقیق قرار دادند و در برخی از این جلسهها آقایان موید ثابتی، نبوی و برخی دیگر از نمایندگان خراسان در مجلس، نیز حضور داشتند.

عکاس: حسین برازنده

سرانجام در تاریخ بیست و چهارم اسفند ماه 1337 بین انجمن آثار ملی و آقای مهندس سیحون قراردادی در 13 ماده امضا شد که به موجب آن مقرر گردید که آقای مهندس سیحون نقشههای آرامگاه خیام و آرامگاه کمالالملک و کارهای تکمیلی آرامگاه و محوطهی آرامگاه اطراف و بناهای تابعهی آنها و خیابان بین دو آرامگاه را تهیه و در اجرای آنها نظارت نماید و بابت نقشه و محاسبات فنی و نظارت معادل پنج درصد کل هزینهی کارها به ایشان پرداخت گردد. به موجب این قرارداد آقای مهندس هوشنگ سیحون متعهد گردیده که نقشههای مقدماتی و همچنین نقشههای قطعی و نقشههای تفصیلی بنای یادبود حکیم عمر خیام را که شامل بنای اصلی و سکوبندی اطراف و آبنماها و بناهای تابعهی آن باشد متدرجا از تاریخ امضای قرارداد تهیه و تحویل نماید. نقشههای قطعی بر اساس ماکت و طرح اولیهای که به تائید دانشگاه رسیده و مورد تصویب انجمن قرار گرفته است حداکثر سه ماه پس از تاریخ این قرارداد و نقشههای تفصیلی بهتدریج تحویل گردد. علاوه بر این مقرر گردیده است که آقای مهندس سیحون مسئول نظارت در اجرای کارهای آرامگاه باشد و یک نفر مهندس دیپلمهی ساختمان که سابقهی کار در کارگاهها داشته باشد از طرف خود در کارگاه بگمارد که به طور دائم اجرای کارها را طبق نظر و دستور ایشان در محل، مراقبت و نظارت نماید و حقوقش به عهدهی آقای مهندس سیحون باشد. به علاوه خود آقای مهندس هر دو ماه یکبار شخصا کارها را در محل بررسی و نظارت نماید و گزارش پیشرفت عملیات را کتبا به انجمن بدهد. ضمنا آقای مهندس سیحون قبول کرده است که برنامهی کار را با مقاطعهکار طوری تنظیم و در اجرای آن مراقبت نماید که ساختمان مقارن زمان گشایش آرامگاه نادر آمادهی گشایش باشد.

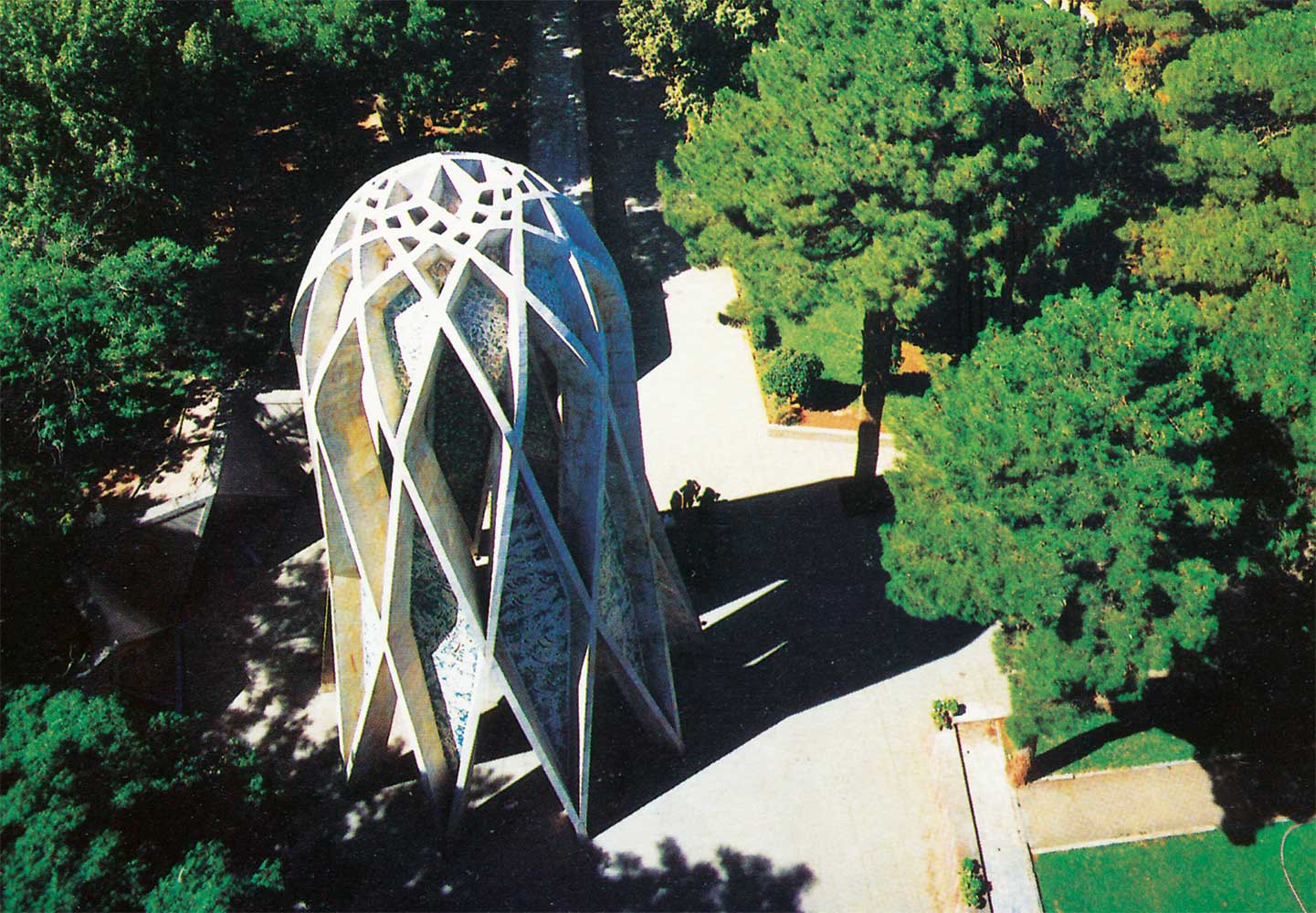

آقایان مهندس سیحون و جودت قسمتی از خصوصیات بنای آرامگاه خیام را طی گزارشی چنین به اطلاع انجمن رسانیدهاند:«…استخوانبندی بنا فلزی و دارای روکش آلومینیوم خواهد بود. در قسمت سقف نوعی شیشههای ضخیم الوان و در متن قسمت بدنه با کاشی پشت و رو تزئین خواهد شد. زیرسازی بنا با بتن و کرسی و راهپله و آبنماها با سنگ گرانیت و بدنهی دیوار مجاور آبنماها با سنگ تراورتن و سنگ روی قبر از سنگ سیاه مشهد خواهد بود. محل آرامگاه در انتهای محور شرقی و غربی باغ و در ابتدای اختلاف سطح موجود واقع است و از کل منظرهی باغ امامزاده محروق استفاده خواهد شد.»

مقاطعهکار

شرکت ساختمانی کا.ژ.ت در تاریخ بیست و دوم آذر 1337 به انجمن آثار ملی اطلاع داد که:«با استحضار از نظر آقای مهندس هوشنگ سیحون نسبت به ساختمان آرامگاه خیام، که باید با بتن ظریف اجرا شود و از هر جهت بدون عیب و قابلقبول آن انجمن باشد این شرکت حاضر است این کار را انجام دهد و در صورتیکه احتاج به متخصصان و کارگران خارجی باشد طبق نظر انجمن و آقای مهندس سیحون از خارج استخدام نماید و کار را به طرز آبرومندی که مورد قبول مهندس ناظر و آن انجمن باشد به پایان رساند.» (بحرالعلومی، ۱۳۵۵)

آقایان مهندس سیحون و جودت طی نامهی مفصلی به انجمن نوشتهاند که:«همانطور که استحضار دارند طرح اولیهی ساختمان آرامگاه خیام با استخوانبندی فلزی تهیه گردید و در نظر بود که روکار آن با آلومینیوم پوشیده شود، پس از مراجعه به اهل فن معلوم شد که روکش آلومینیوم بر فلز آثار نامطلوبی از لحاظ ترکیبات شیمیایی دارد. از این رو تصمیم گرفته شد که کار با طرز بتن ظریف اجرا گردد و ارتفاع آرامگاه نیز از ۱۲ متر به ۲۲ ترقی داده شود تا عظمت بیشتری پیدا کند.

چون از طرفی ارجای مستقیم اجرای کار به دستگاههای خارجی مستلزم تحمل هزینهی زیاد میباشد و از طرف دیگر شرکت مقاطعهکاری (پیمانکاری) کا.ژ.ت حاضر است کار ساختمان آرامگاه مذکور را به مسئولیت خود انجام دهد و در صورت لزوم از کارگران متخصص خارجی نیز استفاده کند این شرکت به طوریکه در ساختمان آرامگاه نادر مشاهده شد مقاطعهکاری است که علاقمندی خود را به حیث مقاطعهکاری ظاهر ساخته است و در اجرای کار دقیق میباشد. آرامگاه خیام از ابنیهای است که باید منتهای دقت در استحکام و حسن اجرای کارهای آن به عمل آید بنابراین صلاح کار در این است که اجرای آن به عهدهی همین شرکت که امتحان خود را داده است واگذار گردد، چون از لحاظ جنبهی فنی اجرای این کار وضعیت خاصی دارد باید به شرکتی واگذار شود که از هر جهت مورد اطمینان باشد. بدیهی است اندک بیتوجهی در این کار ممکن است نظیر آرامگاه فردوسی موجب تاثر و پشیمانی گردد.

آقایان مهندس محسن فروغی، مهندس صادق، مهندس سیحون و جودت نیز صورت مجلسی تهیه و به اطلاع انجمن آثار ملی رسانیدهاند که:«ساختمان بنای آرامگاه خیام که شامل استخوانبندی از فلز و بتن و روکار سنگی و کاشیکاری در قسمت بدنه میباشد کاری عادی نیست که بتوان مشابهی برای آن در خارج داشت، این ساختمان در عین حال که ظریف است باید از لحاظ اجرای کار و تامین استحکام آن دقت فراوان گردد. چون عمده در عملیات مذکور کارهای ظریف است و باید طبق اصول عالی فن در اجرای آن دقت کافی به عمل آید بنابراین انجام دادن آن باید به مقاطعهکاری رجوع شود که علاوه بر داشتن سابقه در کارهای مهم آزمایش خوبی هم در نظایر این کارها داده باشد.» (بحرالعلومی، ۱۳۵۵)

شرکت کا.ژ.ت دارای سابقهی عملیات مهم و مجهز به وسایل لازم میباشد و در کار آرامگاه نادرشاه افشار طبق اظهار نظر آقای مهندس سیحون حیثیت مقاطعهکاری خود را بهخوبی حفظ نموده و کارها را بر قاعدهی صحیح اصول فنی انجام داده است و کارش مورد رضایت آن انجمن و آقای مهندس سیحون، مهندس ناظر میباشد.

لذا امضاکنندگان، رای میدهند که به اتکای مناقصهای که برای آرامگاه نادر طرح شده و بر اساس قراردادی که آن شرکت با انجمن دارد انجام دادن این کار نیز به همان شرکت محول گردد، با مراعات این نکته که چون در اجرای کار ساختمان بنای یادبود خیام عملیات خاصی باید انجام گیرد، ممکن است فهرست بهای قیمت برای بعضی کارهای آن متناسب با بهای قرارداد سابق نباشد که باید قیمت جدید متناسبی منظور گردد.

بازدید چند تن از طراحان و مسئولان صاحبمنصب در نخستین روزهای فروردین ۱۳۴۲.

از سمت راست: هوشنگ سیحون، حبیب یغمایی، تیمسار سپهبد آقولی، دکتر تقی تفضلی، مهندس نکو،

مهندس کنستانتین و سید محمدتقی مصطفوی

ساخت آرامگاه موقت خیام در بحبوحهی جشن هزارهی فردوسی، اثر کریم طاهرزاده بهزاد، ۱۳۱۳

عکاس: شهریار خانیزاد

عکاس: حسین برازنده

در جلسهی هیئت مدیرهی انجمن که در تاریخ دوم دی ماه 1337 تشکیل شد و با توجه به سابقهی عمل شرکت کا.ژ.ت در آرامگاه نادر و توضیحات گزارشهای مذکور و همچنین وضع استثنایی آرامگاه خیام از لحاظ نوع کار چنین تصمیم گرفته شد که برای زودتر عملی ساختن این امر مهم، اجرای آن به عهدهی شرکت کا.ژ.ت گذارده شود و شرکت مذکور تخفیفی را که برای کار آرامگاه نادر پذیرفته است برای این کار هم قبول نماید، زیرا به فرض مناقصه گذاشتن، علاوه بر تعویق کار تصور تخفیفی بیش از آنچه در آرامگاه نادر حاصل شده است نمیرود و مقاطعهکار دیگر هم باید مدتی بگذرد تا امتحان طرز کار و عمل خود را بدهد. به موجب این تصمیم، در تاریخ هفتم دی ماه 1337 از طرف انجمن به شرکت کا.ژ.ت نوشته شد که با پیشنهاد آن شرکت راجع به ساختمان آرامگاه خیام با شرایطی موافقت میشود. در همان تاریخ نامهای نیز به آقای دکتر مهران، وزیر فرهنگ نوشته شد که

به ادارهی کل اوقاف دستور دهند قسمتی از باغ امامزاده محروق را که برای محل آرامگاه خیام در نظر گرفته شده در اختیار نمایندگاه انجمن مقاطعهکار ساختمان قرار دهند و نیز دستورات لازم به ادارات فرهنگ و اوقاف نیشابور صادر نمایند که در اجرای این امر مهم نهایت همکاری را بنمایند.

نصب اولین سنگ بنا

ساعت پنج بعد از ظهر روز سهشنبه 28 اردیبهشت ماه 1338 با حضور استاندار و جمعی از اعضای انجمن آثار ملی خراسان و روسای ادارات و معاریف نیشابور طی مراسمی اولین سنگ بنای آرامگاه خیام نصب گردید. در آغاز این مراسم آقای برهمند فرماندار نیشابور طی سخنانی اظهار داشت که:«در اواخر سال 1337 تیمسار سپهبد آقاولی رئیس هیئت مدیرهی انجمن آثار ملی به اتفاق عدهای از مهندسان و آقای علمی مدیر ابنیهی تاریخی، مسافرتی به نیشابود نموده، از آرامگاه عطار و قبر مرحوم محمد غفاری (کمالالملک) هنرمند فقید بازدید نموده و پس از مراجعهی ایشان به تهران قرارداد تهیهی نقشهی آرامگاه خیام با آقای مهندس سیحون منعقد گردید و اجرای ساختمان به شرکت ساختمانی کا.ژ.ت واگذار شد و اینک گودبرداری این بنا خاتمه یافته است، و امروز اولین سنگ شروع ساختمان نصب میگردد. تعمیر و تکمیل مقبرهی شیخ فریدالدین عطار نیز آغاز گردیده و نقشهی آرامگاه شادروان کمالالملک نیز در دست تهیه است. سنگهای لازم جهت جرزها و کتیبهها و ازارههای داخل و خارج آرامگاهها در مشهد تهیه شده و مشغول حمل آنها به نیشابور میباشند.

عدهای از هنرمندان کاشیساز مشهد نیز مشغول تهیهی کاشیهای نفیسی جهت نمای آرامگاه میباشند. برای ارتباط بین دو آرامگاه خیام و عطار نقشهی جامعی جهت ایجاد خیابانی وسیع و مشجر تهیه شده و اکنون مشغول احداث آن میباشند. چون قسمت عمدهی اراضی این خیابان متعلق به اشخاص بود آقای ابراهیم سعیدی عضو انجمن آثار ملی و باستانی نیشابور از طرف انجمن آثار ملی آن اراضی را خریداری نمودند. برای تامین آب جهت احتیاجات دو آرامگاه و گلکاری و آبیاری اشجار قرارداد حفر یک حلقه چاه عمیق با شرکتی در خراسان منعقد شده و هماکنون هفتاد متر آن حفر گردیده است. در ضمنِ اجرای این کارها برای تعمیرات اساسی بقعهی تاریخی امامزاده محروق نیز که در همین باغ واقع است اقدام به عمل خواهد آمد. انجمن آثار ملی برای چاپ برخی از آثار خیام و عطار و تالیف کتابهایی دربارهی آن دو بزرگ مطالعاتی به عمل آورده و قراردادهایی با دانشمندان و مولفان منعقد ساخته است.» پس از آن آقای رضا جعفری استاندار و رئیس انجمن آثار ملی خراسان لوحهای را که تهیه شده بود در پی بنا قرار داد که در آن نام انجمن آثار ملی و تاریخ آن روز (28 اردیبهشت 1338) نیز ثبت گردیده بود.

و بدین ترتیب از اوایل سال 1338 ساختمان آرامگاه خیام عملا آغاز و قسمتی از کارهای اساسی آن در همین سال انجام گردید که از آن جمله بود:

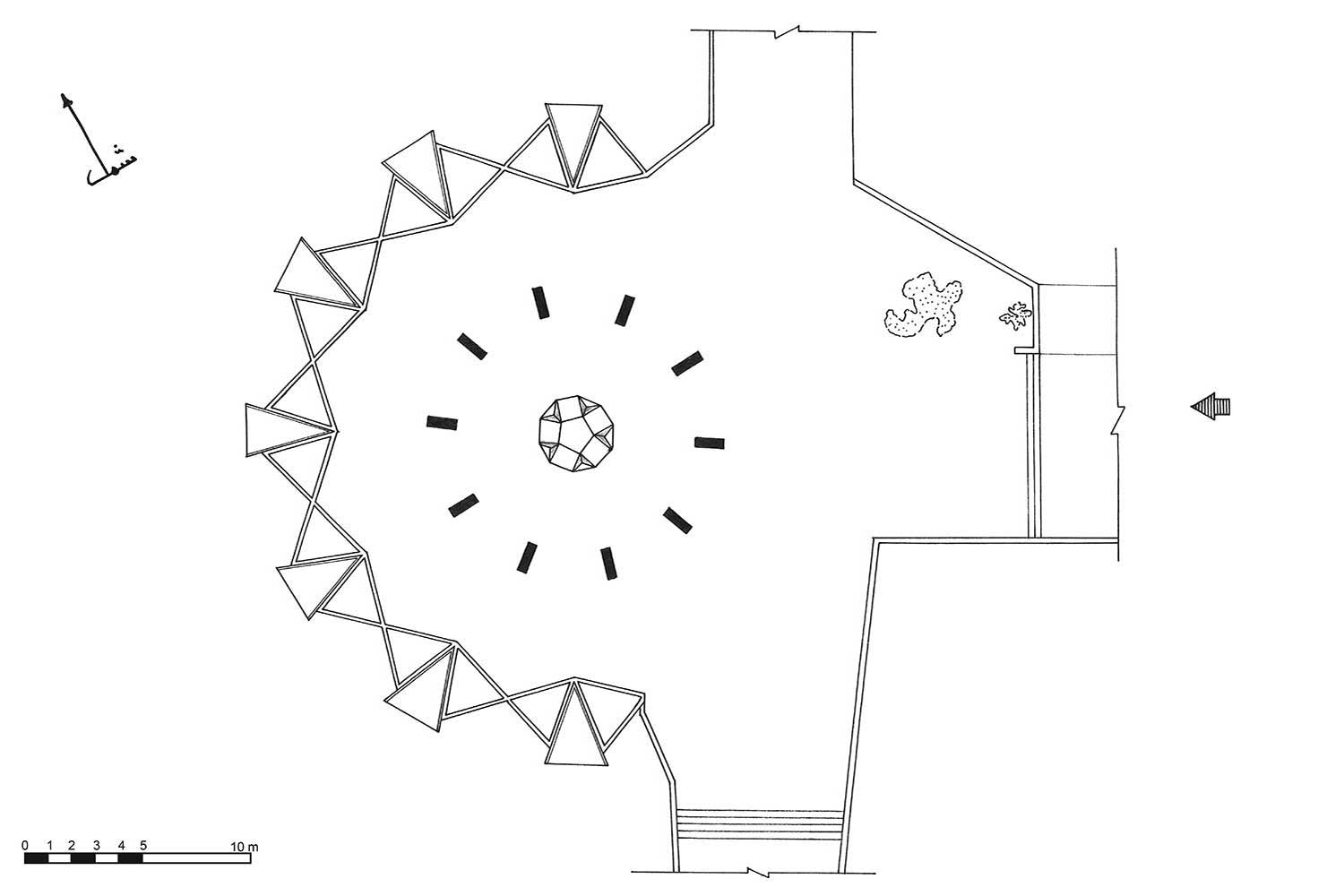

گودبرداری و بتنریزی پیهای جهت بندساختن دیوارهای سنگتراش در اطراف بنا، ساختمان قسمتی از دیوارهای خیابان ورودی باغ، ساختمان قسمتی از پلههای سنگی در مدخل و وسط باغ و پلهبندیهای مختلف دیگر، سفتکاری ساختمان پذیرایی و کتابخانه و دفتر بنا، استوار کردن قسمتی از استخوانبندی فلزی بنا، تهیه و تراش مقداری از سنگهای روکار بنا، تهیهی سنگ گرانیت جهت آبنماهای اطراف بنا و غیره. ضمنا معلوم شد که طرح بتن مسلح ظریف به صورتیکه مورد نظر بوده بهعلت اشکالات فنی در ایران غیرعملی است و به جای آن پیشنهاد گردید که استخوانبندی برج مشبک بنا از آهن ساخته شود و روی آن را با سنگهای تراش نازک نماسازی نمایند و چون اجرای این طرح هزینهی زیادتر و مهلت بیشتری نیاز داشت پس از مدتی مذاکره و بررسی به وسیلهی هیئت مدیرهی انجمن آثار ملی موضوع در جلسهی هیئت موسسین انجمن مطرح و مقرر شد که از طرف هیئت موسسین بررسی بیشتری در محل به عمل آید و در نتیجه در آذرماه 1338 عدهای از آقایان هیئت موسسین به خراسان عزیمت نمودند و با بررسی در جلسههایی که در نیشابور و مشهد تشکیل شد اجرای طرح اخیر یعنی ساختمان بنای یادبود خیام به صورت برج مشبک با استخوانبندی آهنی و روپوش سنگتراش و تزئینات کاشیکاری تصویب و شروع به اجرای آن گردید.

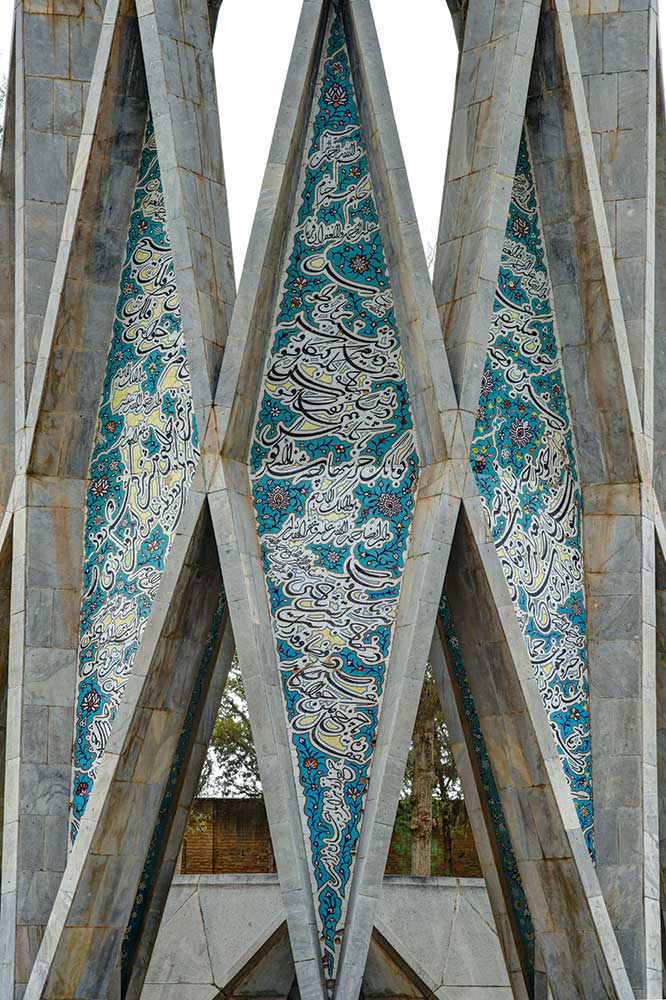

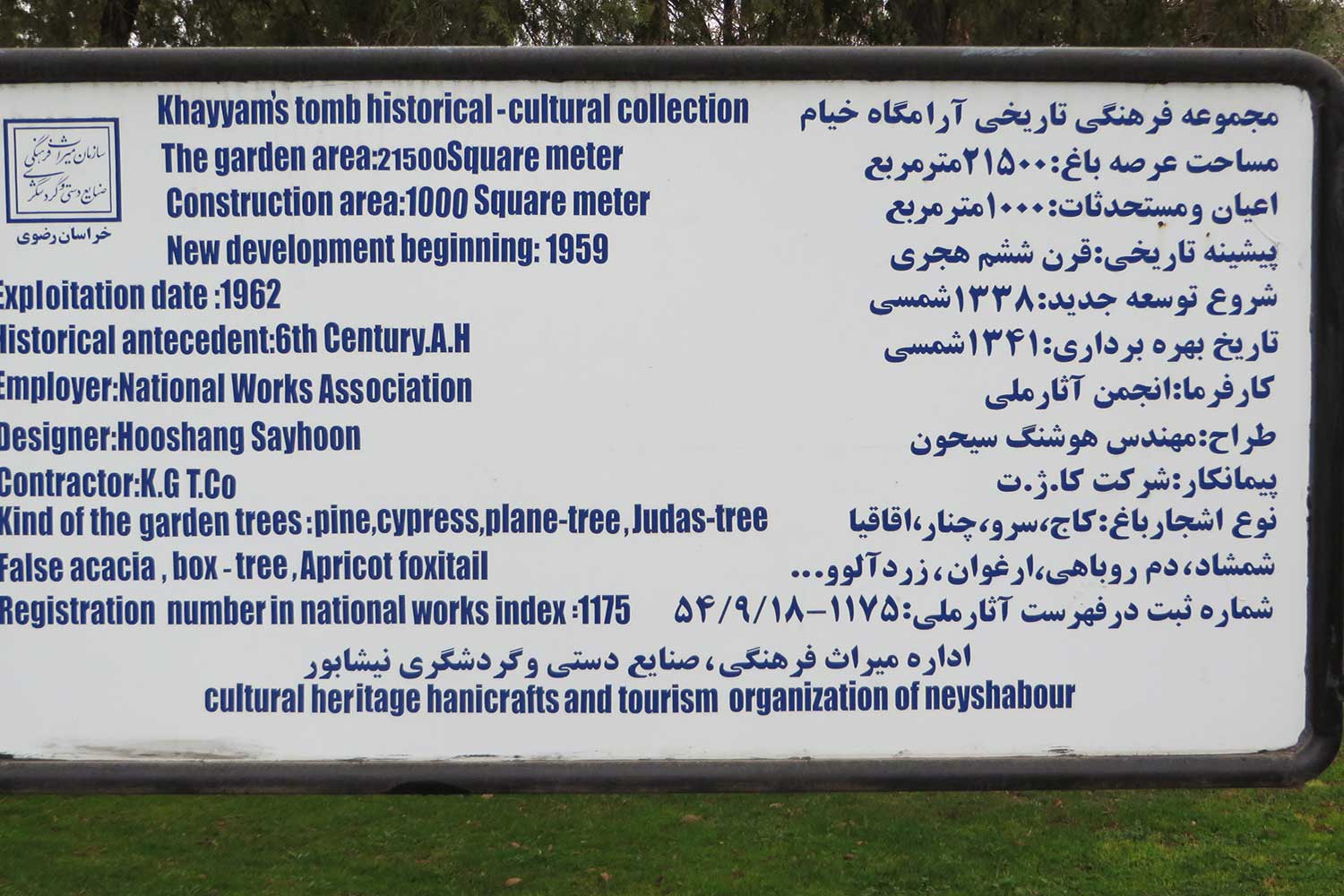

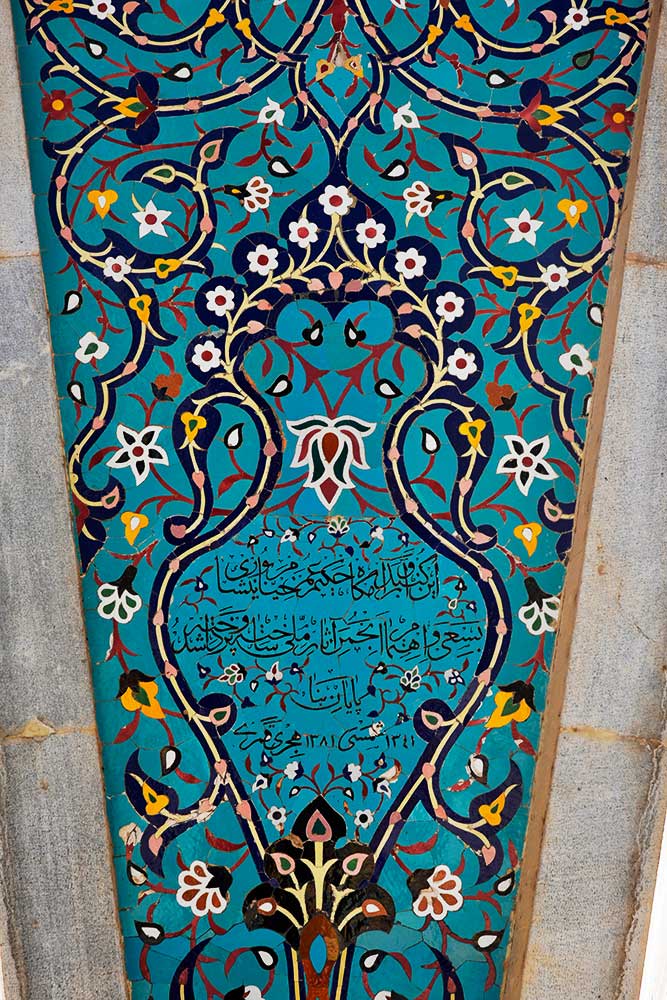

در سالهای 1339 و 1340 کار ساختمان آرامگاه ادامه داشت و قسمتی از آخرین کارهای بنا که در سال 1340 انجام یافت عبارت بود از نصب سنگهای روکار بنا، تهیه و نصب هشت بدنه کاشیکاریهای معرق لوزیشکل شکل بزرگ حاوی رباعیات به خط تعلیق بسیار درشت و نقوش گل و بوتهی اسلیمی در جبهههای خارج و داخل بنا، کاشیکاری معرق سقف زیر گنبد، معرقکاری سنگی روی گنبد، تکمیل آبنماهای سنگ گرانیت در اطراف محوطهی خارج بنا، تکمیل دیوارهای سنگی خیابان روبروی بنا، ساختن دیوارهای سنگی کرسی محوطهی بلندتر واقع در جلوی امامزاده محروق، نصب نردههای سراسری در جلوی کرسی محوطهی امامزاده، پوشش محوطهی بالای آبنماهای اطراف آرامگاه خیام به وسیلهی سنگهای گرانیت نامنظم، آسفالت کردن خیابان ورودی و خیابان جنوبی آرامگاه، تکمیل پیادهروهای اطراف مهمانسرا و دفتر و کتابخانهی خیام، احداث حاشیههای مجاور خیابانها برای گلکاری و چمنکاری در محوطهی باغ آرامگاه، ساختن چهار رشته پلههای سنگی در طول خیابان واقع در محور امامزاده و تهیهی اثاث و لوازم جهت مهمانسرا و دفتر و کتابخانهی خیام از قبیل فرش، مبل، تختخواب و غیره. بدین ترتیب در اوایل سال 1341 کار ساختمان آرامگاه پایان یافت و این اثر شاخص معماری در 18 آذر 1354 به شمارهی 12/1175 در فهرست آثار ملی به ثبت رسید.

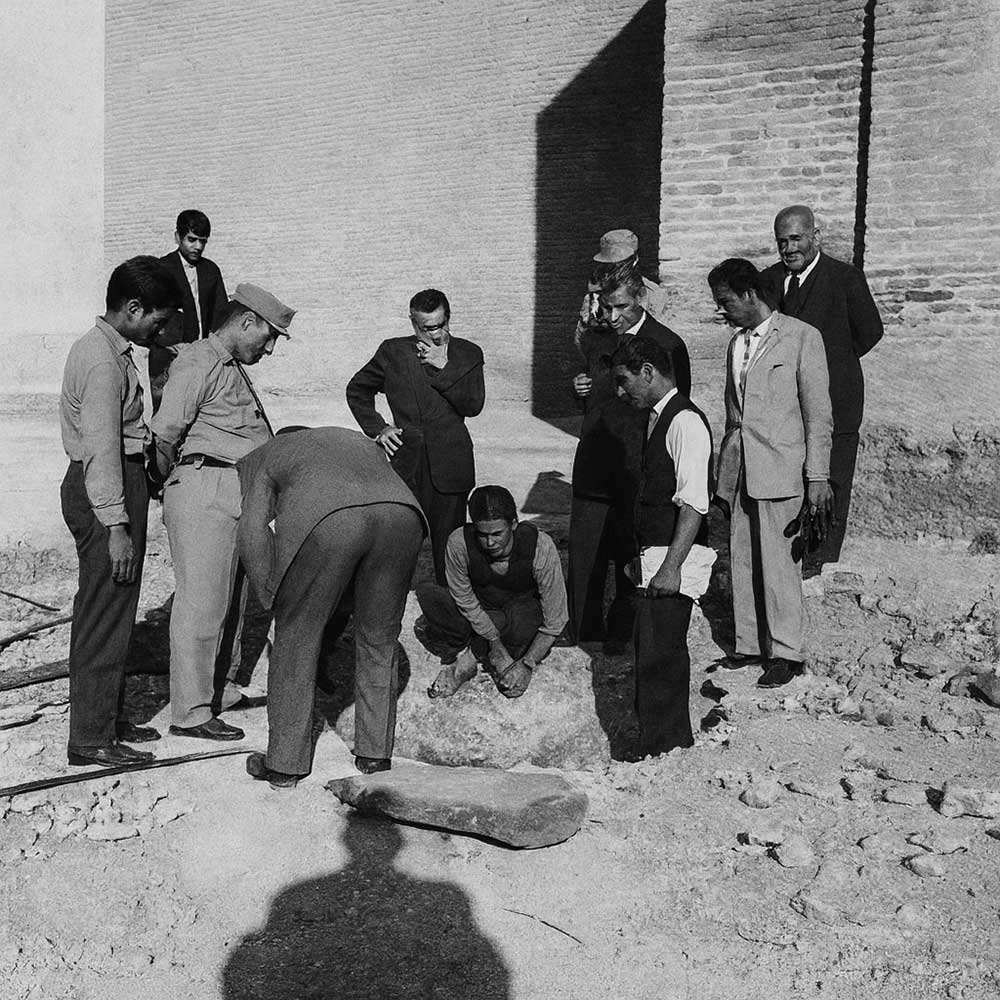

انتقال استخوانهای خیام

در فروردین ماه سال 1341 که ساختمان آرامگاه خاتمه مییافت از طرف انجمن آثار ملی به فرماندار و رئیس انجمن آثار ملی نیشابور و آقای ابراهیم سعیدی عضو انجمن آثار ملی نوشته شد که:«پس از برداشتن آثار مقبرهی سابق حکیم عمر خیام باید عظام نیز با دقت کامل و عکسبردایهای دقیق با حضور نمایندگان انجمن آثار ملی نیشابور و مقامات مربوط و ذیصلاحیت در صندوقی جای داده شود و با انجام تشریفات مذهبی صندوق محتوی استخوانها در محل جدید آرامگاه طبق اصول مذهبی دفن گردد. در این باره قبلا به نمایندهی شرکت کا.ژ.ت اطلاع داده شود که محل دفن در آرامگاه جدید آماده باشد.» (بحرالعلومی، ۱۳۵۵) در روز 29 اردیبهشت ماه 1341 با حضور تیمسار سپهبد آقولی و آقایان دکتر صدیق، تیمسار سرلشکر فیروز، حسن نبوی، دکتر علیاکبر شهابی مدیر کل اوقاف و گروهی از معتمدین و مقامات اداری و اعضای انجمن آثار ملی نیشابور پس از اجرای مراسم مذهبی، استخوانها که در محفظهای قرار داده شده بود به آرامگاه جدید انتقال یافت.

سایت پلان و پلان آرامگاه

آثار بنای آرامگاه سابق

در اسفندماه 1340 آقایان مهندس سیحون و جودت به انجمن آثار ملی گزارش دادند که شهرداری نیشابور در نظر دارد که اثر بنای آرامگاه سابق خیام را به میدانی که مقابل دبیرستان خیام است انتقال دهد و صورت مجلسی تهیه شده است که به ضمیمه ارسال میگردد. در صورت مجلس آمده بود که:«چون با احداث بنای عظیم یادبود خیام در باغ امامزاده محروق لازم بود که اثر بنای سابق به محل مناسب دیگری انتقال یابد در جلسهای با حضور رئیس انجمن شهر، مجتهدی کفیل شهرداری، عبدالله سعیدی وکیل سابق نیشابور، حسن جودت، مهندس سیحون و مهندس کنستانتین تصمیم گرفته شد که آن را به یکی از میدانهای شهر انتقال دهند و چون کارهای آرامگاه خیام تا آخر فروردین سال 1341 پایان مییابد لازم است که عملیات مربوط به انتقال تا آن تاریخ انجام گردد.» (بحرالعلومی، ۱۳۵۵)

ساختمان آرامگاه

فرامرز پارسی مینویسد:«با دولتی شدن آرامگاهسازی، ساخت آرامگاهها دو مسیر جداگانه را پیمودند. یکی امامزادهها و آنچه با وقف معتقدین به کرامات این امامزادگان یا امامان ساخته میشد و دیگری مقابر شعرا و ادبا و دانشمندان که با بودجههای دولتی انجام میشد. مسیر اول همچنان تابع زبان معماری تاریخی بوده و البته با تحولاتی در تزئینات، به خصوص گرایش به سمت تزئینات متکلف چون آینهکاری و مسیر دولتی که در آغاز با مقبرهی حافظ و فردوسی در زمان پهلوی اول انجام شد و ترکیبی از معماری ایرانی و نئوکلاسیک غربی را دستمایهی طراحی قرار میداد. با ورود معمارانی چون فروغی و سپس سیحون گرایشی از معماری خلق شد که به جرأت میتوان آن را تاثیرگذار بر معماری دههی آخر پهلوی دانست. این معماران که در عین تبعیت از اصول معماری مدرن شیفتهی معماری ایرانی نیز بودند دست به ترکیبی از نشانههای معماری ایرانی با فردگرایی و نوگرایی معماری مدرن زدند. از مشخصات این آرامگاهها توجه معمار به ویژگیهای زندگی فرد میباشد. مسائلی چون ریاضیدان بودن یا شاعر بودن، چیزی که تا پیش از این در معماری مقابر موضوعیت نداشت. در فرم نیز اگرچه متاثر از برج مقبرههای تاریخی هستند ولی ترکیب کاشی و سنگ تم اصلی مصالح در این معماری را شکل میدهد و استفاده از کاربندی با نگاهی مدرن نیز گرایشی رایج محسوب میشود.»

آرامگاه عمر خیام از لحاظ معماری یک بنای نمونه است چنانکه مجلهی معروف Japan architect در شمارهی ژانویهی 1963 خود بنای آرامگاه خیام را از نظر طرح و جنبههای هنری مورد ستایش قرار داده است. این آرامگاه در باغ بزرگی در خارج از شهر نیشابور قرار دارد و به فاصلهی دو کیلومتری غرب آن، باغ دیگری است که آرامگاه عارف بزرگ ایران، عطار نیشابوری نیز در آنجا قرار دارد. چنان که گفته شد، مزار خیام در ابتدا چسبیده به امامزاده محروق بود اما آرامگاه جدید بر محوری در جهت آرامگاه عطار ساخته و همچنین جادهایی برای ارتباط بین دو آرامگاه کشیده شد. آنطور که ذکر شد، هوشنگ سیحون پیرو وصیت خیام، مکانی در باغ انتخاب کرد که اختلاف ارتفاع سهمتری با درختان زردآلوی باغ داشت تا هر بهار، شکوفهها بر مزار خیام بریزند. او میگوید که این کار، یعنی جابهجایی محل دفن، را در مورد هفت شخصیت انجام داده است: خیام، عارف قزوینی، ابوسعید دخدوک، نادرشاه افشار، کلنل محمدتقیخان پسیان (سردار خراسانی)، ابوعلی سینا و فردوسی.

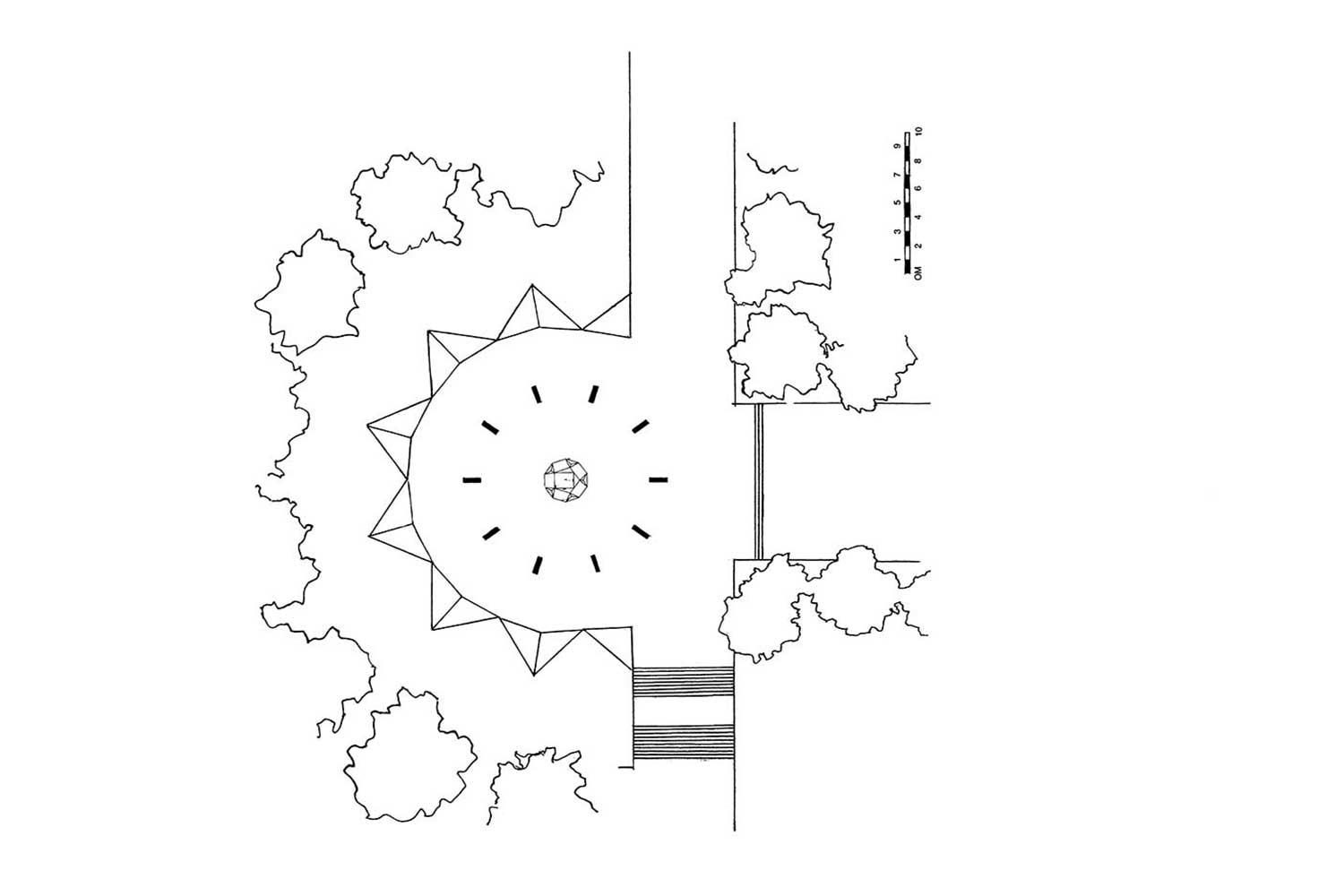

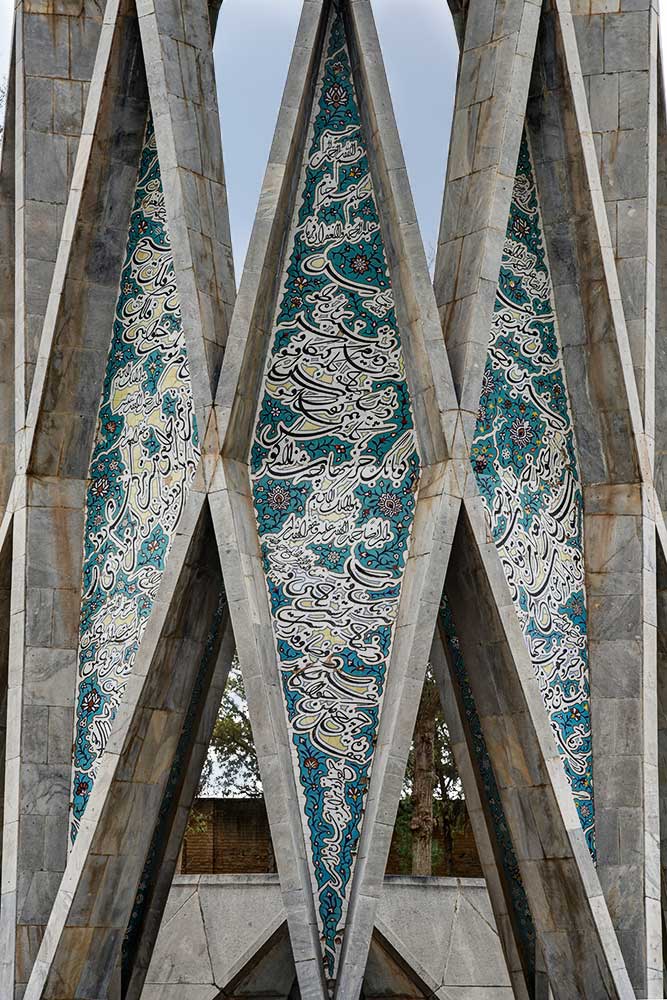

طراحی آرامگاه جدید حکیم عمر خیام با توجه به شخصیت وی که دانشمند، ستارهشناس، فیلسوف، ریاضیدان، شاعر و رباعیسرای بزرگ ایرانزمین بود، صورت گرفته است. در معماری بنای یادبود وی تاکید به مسائل هندسی و نجوم و همچنین الهام گرفتن از باغهای ایرانی چنین مینماید که مجموعه به همراه آبنماهای سنگی هفت گانهی مثلثی گرداگرد آن که با توجه به افلاک و ستارگان، در قالب اَشکال منتظم دهضلعی و مخروط گنبدیشکل مشبک و دارای تزئینات کاشیهای معرق با خطوط تعلیق شکسته ساخته شده، همه و همه نشان از رویکرد ناب و تفکر عمیق و هنرمندانهی هوشنگ سیحون در باب این حکیم شهیر دارد.

چشمهها به دور نیمدایرهی بزرگی به مرکز برج یادبود که از جنس گرانیت است، ساخته شدهاند و با برآمدگیها و فرورفتگیهای مثلثی خود شکل خیمه را تداعی میکنند –خیام نیز به معنی خیمهدوز است و این نام که اشاره به شغل پدر او دارد، موتیفی است که بارها در این طرح سیحون لحاظ شده است و سیحون با این کار قصد داشت نام خیام را در چشمهسارهای اطراف مقبرهاش منعکس کند.

امیر بانیمسعود در کتاب معماری معاصر ایران ایده ی اصلی کار از زبان هوشنگ سیحون اینطور نقل میکند:

«در سی و چند سال پیش، که انجمن آثار ملی تصمیم گرفت بنای مناسب برای خیام ایجاد کند، طرح آن را به عهده ی اینجانب گذاشتند. چون در جوار امام زاده، امکان ایجاد ساختمان بزرگ قابلتوجهی نبود، به ناچار محور عرضی دیگری در باغ به وجود آوردم که عمود بر محور اصلی است و ورودی بنای خیام از همین محور در نظر گرفته شد. به خصوص که این محور در جهت باغ عطار نیز بود. یعنی از همین ورودی جاده ی دیگری کشیده شد که باغ امام زاده و خیام را به باغ عطار ارتباط میداد.

دایرهی کف به 10 قسمت با فواصل 5 متری تقسیم شد، به طوریکه برج یادبود بر 10 پایه مستقر باشد. عدد ده، اولین عدد دو رقمی در ریاضی و پایهی اصلی بسیاری از اعداد است. از هر یک از پایهها، دو تیغهی مورب به طرف بالا حرکت میکند، به ترتیبی که با تقاطع این تیغهها، حجم کلی برج در فضا ساخته میشود و چون تیغهها مورباند، خطوط افقی آنها باید ناظر به محور عمودی برج باشد. پس تیغهها به صورت مارپیچ به طرف بالا حرکت میکنند تا با هم تلاقی کنند و از طرف دیگر سر در بیاورند که خود، یک شکل پیچیدهی ریاضی و هندسی است. […] برخورد تیغهها با یکدیگر، فضاهای پروخالی و به خصوص در بالا، ستارههای درهمی را به وجود میآورد که از لابهلای آنها آسمان آبی نیشابور پیداست و نوک گنبد، بهتدریج به طرف ستارهها کوچکتر میشود تا آخر یک ستارهی پنجپر آنها را کامل کند. این ستارهها و آسمان، اشاره به شخصیت نجومی خیام دارند. برخورد تیغهها با هم، 10 لوزی بزرگ میسازند که باید با کاشیکاری پُر شوند. بهترین تزئین، استفاده از رباعیات خود خیام بود که به صورت خط شکسته و درهم به روش سیاهمشقهای خطاطان بزرگی مانند میرعماد و بعضی استادان شکستهنویس با کاشی به صورت نقوش انتزاعی، سرتاسر لوزیها را پر کنند. […] از طرف دیگر، حوضها از سنگ گرانیت با پوشش کاشی فیروزه هستند که در مجموع، قسمتی از ستاره را نشان میدهند، به تعداد هفت پر به مفهوم هفت فلک و هفت قبّه که باز اشاره به افلاک و نجوم، دانش دیگر خیام دارد و نیز نمادی از خیمه است. روی هم رفته، مجموعه در یک حالوهوای شاعرانه با درختان تنومند در اطراف ساخته شده است. و همانطور که خواست خود خیام بوده، کاملا باز است و مزارش در بهاران، گل افشان میشود.

فضای داخل لوزیهای بزرگتر در پایین بنا از دو سمت با کاشیهای معرق تزئین یافته و بسته شده؛ به این ترتیب که در جبههی خارجی هر لوزی، دو رباعی به خط شکسته و تعلیق به صورت درهم و کوچک و بزرگ و با زینت کاشی معرق، نماسازی شده است. از داخل نیز قسمتهای پر -از جمله همین لوزیها- با نقش گل و برگ و پیچکِ باز از هم، با کاشی معرق تزئین گردیدند.

انتقال استخوانهای خیام به داخل آرامگاه جدید

بیرون آوردن استخوانهای خیام از مدفن سابق حکیم

اقامهی نماز بر استخوانهای خیام

در طراحی هوشنگ سیحون لوزیهای وسط، خالی و باز گذاشته شدهاند و قاببندیها با سنگهای ظریف و شفاف انجام شده و سطح لوزیهای داخل آنها از دو جانب با کاشیهای معرق تزئین یافته و بسیار جلوهی زیبایی دارد و همگی اشاره به شخصیت شاعری خیام دارند لازم به ذکر است که (برخلاف ایدهی نقاشیخط و اجرای آن که امری کاملا جدید بود) شیوهی قاببندی کاشی به وسیلهی سنگ در بناهای تاریخی سابقه دارد، از آن جمله در بنای تاریخی درب امام اصفهان، متعلق به دو امامزاده ابراهیم و زین العابدین، از نوادگان حسن مثنی و علی بن جعفر(ع) (880 ه.ق) نمونههای عالی کاشی معرق با قابسازی سنگ مرمر دیده میشود و در بنای مسجد مولانا در تایباد از آثار زمان شاهرخ تیموری و همچنین در مسجد کبود تبریز (به تاریخ 870 ه.ق) که در هر دو بنا ظریفترین و عالیترین نمونههای کاشی معرق ایران موجود است، نیز سنگ و کاشی را به شیوهای مشابه با طرحی زیبا و هنرمندانه تلفیق نموده و در کنار هم به کار بردهاند.

در جبههی خارجی آرامگاه خیام نیز از سنگهایی که با استقامتتر از سنگ مرمر و در عین حال از حیث رنگ و شفافیت، مناسب با کاشیهای معرق بنا میباشد استفاده شده است. اشکال مثلث و لوزی که بر اضلاع دهگانهی آرامگاه خیام مشاهده میشود به سبب شکل دایرهای بنا و انحنای آن در جهت عمودی به صورت مثلثها و لوزیهای غیرمستوی است و در سراسر بنا خمیدگیهایی دارد و به همین سبب سنگها با انحنایی مناسب هموار گردیده است. سقف زیر گنبد با کاشیهای معرق و قسمت خارجی گنبد با معرق سنگی پوشیده شده است. در کنار آرامگاه، هفت خیمهی سنگی بسیار زیبا وجود دارد و در زیر هر یک حوض آب با کاشی فیروزهای رنگ ساخته شده و ریزش آب در آنها منظرهای بدیع ایجاد کرده است و در گرداگرد محوطهی خارج بنا در پشت برج آبنماهایی از تخته سنگهای عظیم گرانیت با طرحهای هندسی هرمی شکل تعبیه گردیده است. بیست رباعی منتخب از خیام که بر جبههی خارجی ده ترک لوزی شکل با خط تعلیق با کاشی معرق نقش گردیده بر طبق درخواست انجمن آثار ملی به وسیلهی استاد جلالالدین همایی انتخاب و به خط آقای مرتضی عبدالرسولی نوشته شده است و آقای مصطفی طباطبایی کاشیکار اصفهانی و دستیاران همشهری او با کاشی معرق آنها را تهیه و نصب کردهاند.

محسن اکبرزاده، معمار و پژوهشگر معتقد است: «هرچند میتوان با تبارشناسی، مقبرهی خیام را گنبدی ترکبندی شده و بدون پوش دانست، اما باید تسلیم شد و قبول کرد که آنچه معمار آفریده در سنتاش بیمانند است. بیمانندی در عین پیشینهدار بودن، یعنی به معاصریت آن سنت رسیدن. این با معاصرسازی مرسوم فرق دارد که بنایی مدرن آفریده شود و از تن سنت، اجزائی را مانند چاشنی به آن بیافزایند و یا ساختاری سنتی چون گنبد را با اطوار یا اجزای مدرن بازآفرینی کنند. در معاصرسازی همواره نوعی رابطهی غالب و مغلوب میان امر سنتی و امر مدرن توسط معمار پذیرفته میشود. ولی در مقبرهی خیام با معاصریت یک سنت طرفیم. چه آنکه آذین کاشی بنا نیز در همین وضع است. خطی که به کار رفته، قطاعبندی هندسی ترکها، گشودگی رو به آسمان قطاع غیرباربر کاربندی افراز و حتی نوع وصل شدن گنبد به زمین، هیچیک معاصرسازی نیست. اینکه تداوم ترکبندی با جرزهایی که توان باربری بیشتری دارد اجازه داده تا به جای چهار طاق، ده طاق روی زمین حادث شود، تمنای هموارهی معمار سنتی ایرانی بوده است که تنگنای مصالح امانش نمیداده است. حتی تداوم هندسه در محوطهسازی، عین تداوم گنبدخانهی میانی در طاقبندی رواق دور ارسنهای ایرانی رقم خورده هر چند، ترکیببندی آن آموزهای مدرن است»

همچنین الهه نجفی دربارهی معماری این بنا معتقد است:«مقبرهی حکیم عمر خیام نیشابوری و شهر نیشابور، هریک به نحوی در ماندگاری نام یکدیگر موثر و وامدار دیگری هستند. هویت تاریخی و آسمان نیشابور بر مقبرهی خیام و مقبرهی خیام بر هویت شهری و صنعت گردشگری شهر نیشابور در 59 سال گذشته تاثیرگذار بوده است، چنانچه غالبا اولین تصویر ذهنی از شهر نیشابور، تصویر آرامگاه خیام است. موقعیت مکانی آرامگاه که کمی با فاصله از هیاهوی شهر و در دل باغ جانمایی شده، آن را در مقایسه با برخی آثار مشابهش چون آرامگاه بوعلی سینا، ازحیث آسیبهای محیطی مصون نگه داشته است.

طراح بیبدیل اثر، پدر معماری مدرن ایران، استاد هوشنگ سیحون نیز در این بستر مناسب، طی بازیهای هوشمندانه و تکنیکهای منحصربهفرد، در تقابل و تضادهای بصری که در ذیل به برخی از آنها اشاره خواهیم کرد، هنر خود را به رخ ناظر کشانده و بر دلربایی آن افزوده است.

• ابعاد خداگونه و فراانسانی آرامگاه از یک سو و حس در بر گیرندگی و خضوع طرح از دیگر سو، ابهت و مردمواری را در این حجم در کنار هم نشانده است، آنچه به کمال در شخصیتشناسی خیام نیز محل سخن است.

• به کارگیری هستهی فلزی و پیکربندی بتنی، در عین حال ایجاد شفافیت و گشایشهای مدولار و خلق پرسپکتیوهای متنوع به باغ و آسمان باعث شده بنا با وجود عظمت، سبک، شفاف و سیال جلوه کند و طبیعت را در بر گیرد.

• توجه و بهرهگیری از تمام زمینههای علمی حکیم خیام و ایجاد ارتباط معنادار میان ریاضیات، نجوم و ادبیات و نیز تبلور آنها در ایدهپردازی، از دیگر نکات قابل تامل در طراحی این اثر است. اشکال هندسی، اعداد، صور فلکی، همگی به خدمت معمار درآمدهاند، بلوغ فکری وی را به رخ ناظرین میکشند و طرحی یکپارچه ارائه میدهند که هر لحظه معماگونه با موشکافی ناظر، رازی از خویش عیان میسازد. این معماگونگی طرح و به چالش کشیدن ناظر، اشارهای به غایت موضون بر لقب اصلی خیام دارد که جهانیان او را با عنوان نابغهی پرسشگری میشناسند.

• توجه و تداوم یک ایده در کلیات و جزییات طرح همان چیزی است که طراحی را یکپارچه و چشمنواز میکند. تکرار ترکیببندیها، المانها و وفاداری به خط مشی الهامبخش طرح، از سنگ مقبره تا طراحی محوطه با مهارتی ستودنی یکپارچگی خاصی به طرح بخشیده است. کافیست از بیرون بنا با نگاهی به یکی از حفرههای لوزیشکل به سوی باغ نظاره کنید، تکرار، تسلسل و قابهای بیبدیلی را تجربه خواهید کرد.

• و سرآخر، گستراندن بنا بر بستر طرح، چنانچه گویی به آن زمین تعلق داشته و بر آن ریشه دوانده است، ضرورتی که استاد سیحون به زیبایی هرچه تمام در این اثر بر آن اهتمام ورزیدهاند.

ادوارد فیتزجرالد، مترجم رباعیات خیام به انگلیسی

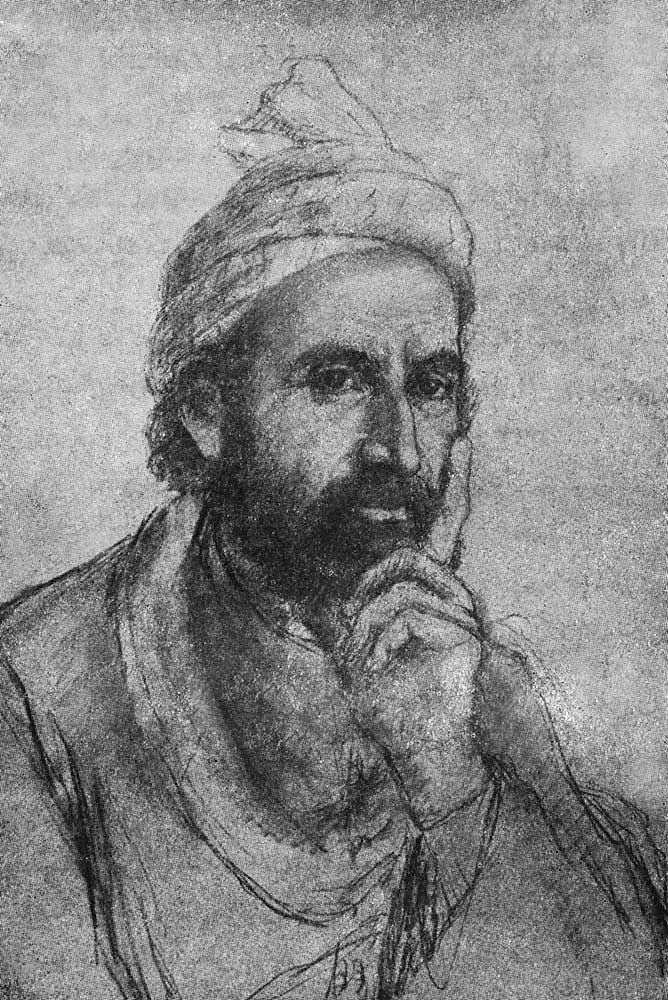

تصویر خیام به طراحی محمدعلی حیدریان

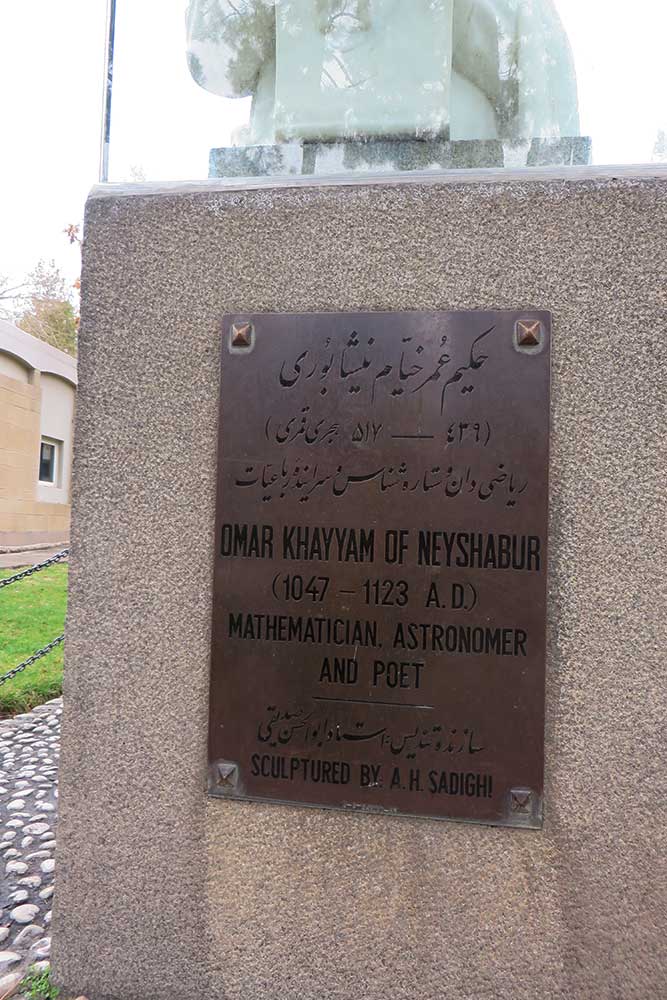

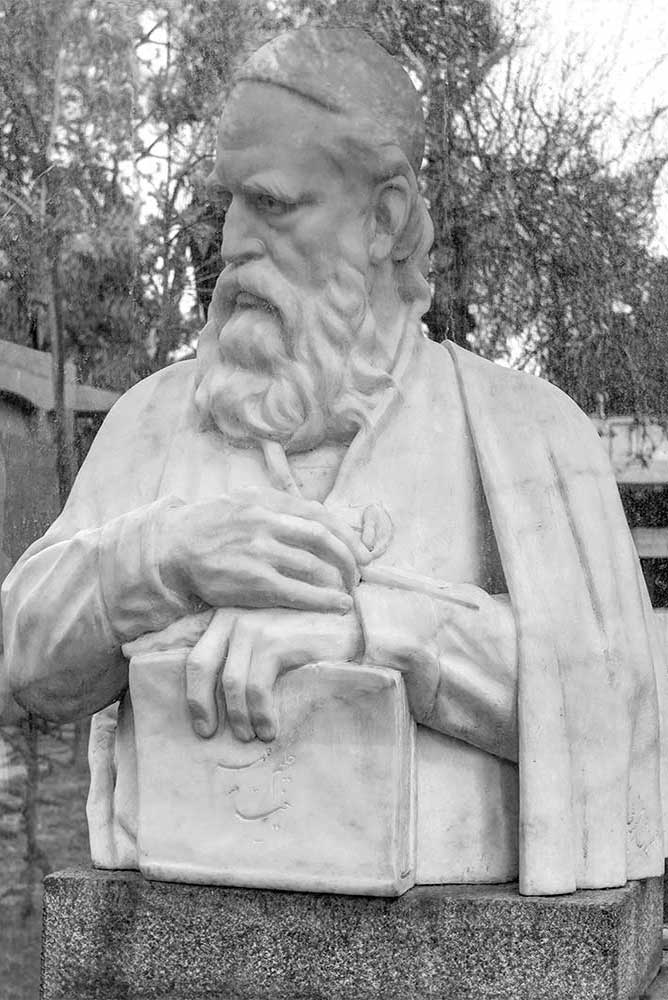

نیمتنهی خیام، اثر ابوالحسن صدیقی

طراحی خیمهگونه (با اقتباس از زندگی خیام)، ترکیبی از حوضهای فیروزهای، هرمهای گرانیتی و جویهای روان که در مجموع حول مرکز دایرهی برج، خیمهوار آن را در برگرفته و چون دامنی بر زمینه باغ خرامیدهاند و سبزینگی باغ را از آن خود کردهاند نیز قابل توجه است. آرامگاه خیام علاوه بر اینکه به عنوان بنایی با ارزش در بستر زمانی خود چشمنواز است، الگویی ارزشمند برای خوب دیدن، نحوهی ایدهپردازی، بهرهگیری از هنر، علوم، طبیعت، تحلیل همه جانبهی صورت مسئله و در نهایت طراحی برای معماران است.»

محوطه و محل آرامگاه

محل بنای آرامگاه چنانکه اشاره شد در گوشهی شمال شرقی باغ امامزاده محمد محروق قرار دارد و خیابان بزرگ شمالی جنوبی باغ با وضع اصلی محل و درختهای کهنسال آن محور و چشمانداز اصلی بقعهی مذکور را تشکیل میدهد و بنای آرامگاه خیام در جانب شمال شرقی همین خیابان به مسافت کمی از آن احداث شده و خیابان دیگری در محور آن رو به مغرب ایجاد گردیده و ورودیهی باغ هم در جانب غربی باغ ترتیب یافته است. به علت اختلاف سطح داخل باغ کف خیابان اصلی سابقالذکر و سطح زیرین بنای آرامگاه خیام پایینتر از محل بقعهی امامزاده و محوطهی روبروی بقعه قرار گرفته است و در نتیجه منظر و موقع امامزاده که بنایی مذهبی و تاریخی است محفوظ مانده است. با توجه به وضع زمین باغ، قرار گرفتن آرامگاه خیام در گوشهی محوطه به صورتیکه یک طرف آن دیوار سنگی و طرف دیگر پلکانی برای بالا رفتن به بالای آبنماهای اطراف برج میباشد منظرهای زیبا ایجاد کرده است، در محوطهی بالای آبنماها که همسطح با قسمت بلندتر باغ است درختهای بید کاشته شده و با پراکنده شدن شاخههای آنها در فضای برج بر سرسبزی و طراوت محوطه افزوده خواهد شد و دیوارههای بلند کرسی بنا با سنگ ساخته شده و بین کرسی محوطه و بقعهی امامزاده محروق نردههای کوتاه سراسری نصب گردیده است.

تصویر هوایی از آرامگاه خیام و امامزاده محروق در سایت

تمام محوطهی آرامگاه از چمن و گل و سبزه پوشیده شده و پیادهروهایی در اطراف مهمانسرا و دفتر و کتابخانهی خیام ساخته شده است. در باغ آرامگاه در کنار خیابانها حاشیهها و سینهمالهایی برای گلکاری و چمنکاری احداث گردیده و خیابانهای ورودی و جنوبی آرامگاه آسفالت شده و دیوارهای خیابان مقابل آرامگاه با سنگ پوشیده شده است. ضمنا با تعمیرات و ترمیمات وسیعی که در بقعهی امامزاده محروق صورت گرفته بر شکوه و نزهت آرامگاه خیام بسیار افزوده شده است. چراغهای پایهداری در محوطه تعبیه شده و در پای هر یک صفحهی فلزی سه گوش سیاهی نصب شده تا در محوطهی آرامگاه سایه روشن مناسب با خاموشی و سکوت ابهتآمیز چنین مکانی فراهم آید. به طور کلی باغ و آرامگاه خیام را از هر حیث میتوان از نقاط خوش منظره و دیدنی و زیبا به حساب آورد.

دفتر، کتابخانه، تالار پذیرایی

در قسمت شمال غربی باغ خیام، عمارت دفتر با تمام وسایل لازم قرار دارد. ابعاد اتاق دفتر 4.46 * 3.70 میباشد و بر دیوار غربی آن سنگی نصب شده و قصیدهی آقای ابراهیم صهبا به همراه مقدمهای بر روی آن نقر شده است. کتابخانهی خیام به ابعاد ۶.۹۰*۶.۹۰ متر در شرق دفتر آرامگاه واقع است و در زمان افتتاح بیش از پانصد مجلد کتاب به آن اهدا شده بود. در شمال دفتر و کتابخانه، تالار پذیرایی با تمام لوازم آن قرار دارد، این تالار ابعادش 11*4.25 متر میباشد. مهمانان و شخصیتهای داخلی و خارجی که برای بازدید آرامگاه میآیند در این تالار پذیرایی میشوند. در شمال غربی باغ، ساختمان مخصوصی مشتمل بر چهار اتاق به نام مهمانسرا به صورت آبرومندی بنا گردیده و لوازم آنها از قبیل فرش و میز و صندلی و قفسه و چراغ و تختخواب و حمام و بخاری و غیره فراهم گشته است.

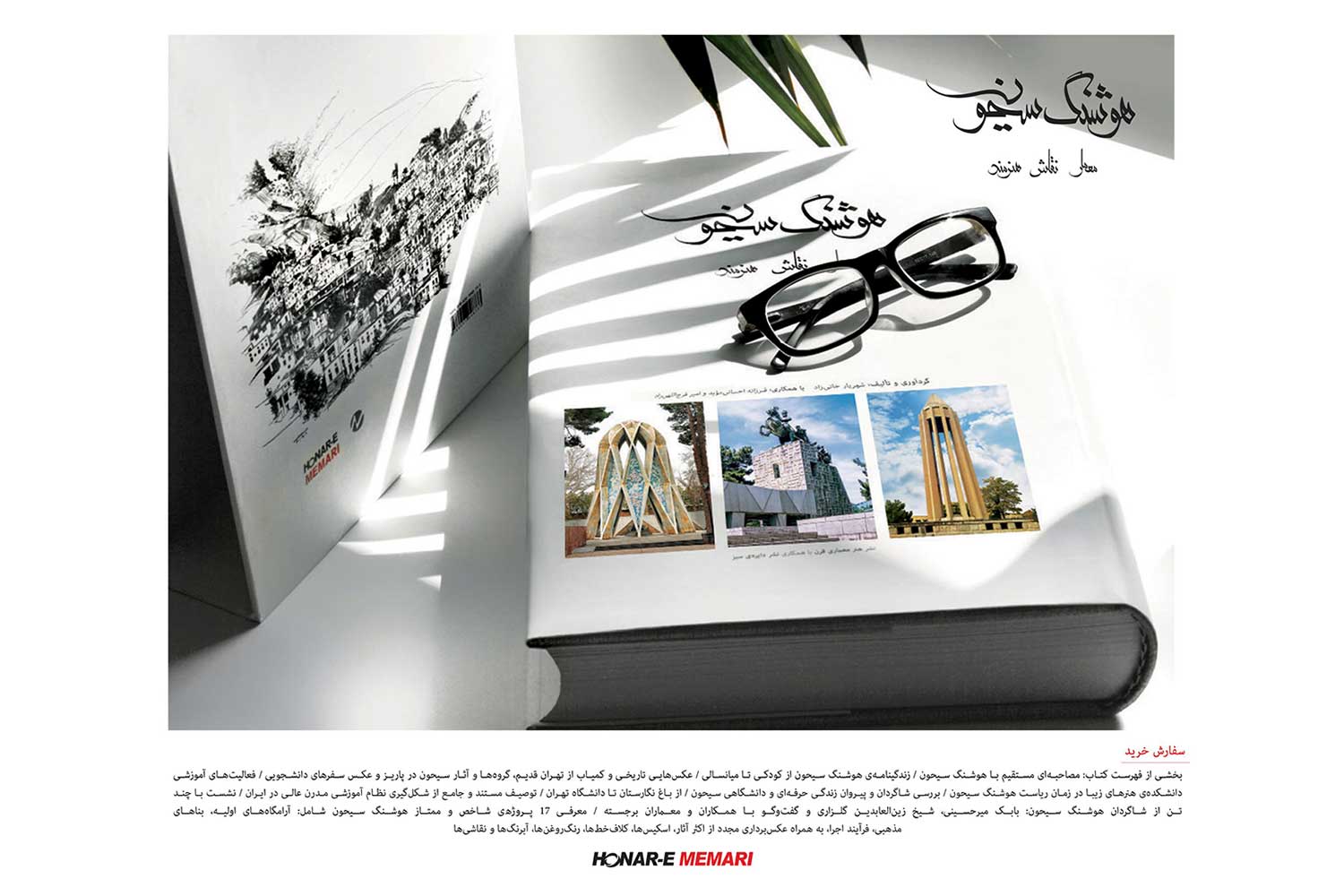

تصویر خیام و تالیف کتب دربارهی او

به منظور تهیهی تصویری از خیام که مانند تصاویر سعدی و فردوسی و ابن سینا مورد تصویب انجمن آثار ملی قرار گیرد در مهرماه سال 1341 جلسهای با حضور آقایان دکتر صدیق و دکتر رضازادهی شفق و مهندس هوشنگ سیحون و اکبر تجویدی معاون دانشکدهی هنرهای تزئینی و شیرزاد نمایندهی انتشارات رادیو و هیئت مدیرهی انجمن، انجمنی تشکیل گردید. در این جلسه گفته شد که اینک که آرامگاه مجلل و آبرومندی به وسیلهی انجمن آثار ملی بر تربت حکیم عمر خیام ساخته شده تهیهی تصویر خیام لازم مینماید و به خصوص که تهیهی تصویر خیام به منظور ساختن مجسمهی او نیز لازم است. در این جلسه همچنین گفته شد که انجمن آثار ملی در نظر دارد تصویری از شاعر معروف انگلیسی فیتز جرالد که بهترین و معروفترین مترجم رباعیات خیام است تهیه نماید تا در تالار کتابخانهی مجاور آرامگاه خیام نصب گردد.

آنگاه مطالبی که دربارهی شخصیت خیام با بررسی دقیق در احوال و آثار او و همچنین نقل قولهای معاصران وی فراهم آمده بود مورد بحث و مطالعه قرار گرفت و مقرر شد که پس از آن نیز به طرق مختلف تحقیقات و مطالعاتی در این باره به عمل آید. سرانجام تهیهی تصویر حکیم عمر خیام به عهدهی آقای استاد محمدعلی حیدریان گذارده شد و استاد بر مبنای مطالعات و تحقیقاتی که به عمل آمده بود ابتدا طرح سیاه قلم تصویر را تهیه کرد و پس از تائید و تصویب انجمن آثار ملی تصویر حکیم عمر خیام با رنگ روغن ساخته شد. تصویر فیتس جرالد نیز به وسیلهی استاد حیدریان تهیه گردید. مجسمهای از نیمتنهی عمر خیام از جنس سنگ مرمر سفید یکپارچه به سال 1349 توسط استاد ابوالحسن صدیقی و به سفارش انجمن آثار ملی، در رم تهیه و در شمال خیابان ورودی باغ آرامگاه حکیم نیشابوری و در باغچهی جنوبی مهمانسرا قرار داده شد. همچنین مقارن بنای آرامگاه و پس از آن، کتابهایی که یا از آثار خیام و یا دربارهی آن حکیم بزرگ است به وسیلهی انجمن آثار ملی چاپ شده است.

عکاس: حسین برازنده

The Mausoleum of Ḥakīm ʿUmar Khayyām, Designed by Houshang Seyhoun

Through the Efforts of the Society for National Heritage

Khwāja Imām Ḥujjat al-Ḥaqq Abū al-Fatḥ ʿUmar ibn Ibrāhīm Khayyāmī of Nishapur, known as Ḥakīm ʿUmar Khayyām, was one of Iran’s greatest mathematicians, philosophers, and poets. The earliest sources in which Khayyām is mentioned—apart from Sanāʾī’s letter to him—include, in order: Chahār Maqāla by Niẓāmī ʿArūḍī Samarqandī, Mirṣād al-ʿIbād by Shaykh Najm al-Dīn Abū Bakr Rāzī (known as Dāya), Nuzhat al-Arwāḥ wa Rawḍat al-Afrāḥ fī Tārīkh al-Ḥukamāʾ al-Mutaqaddimīn wa al-Mutaʾakhkhirīn by Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Maḥmūd al-Shahrazūrī, Kāmil al-Tawārīkh by Ibn al-Athīr, Taʾrīkh al-Ḥukamāʾ by Qāḍī Akram Jamāl al-Dīn Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Yūsuf al-Qifṭī, Āthār al-Bilād wa Akhbār al-ʿIbād by Zakariyyā ibn Muḥammad ibn Maḥmūd al-Qazwīnī, Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh by Rashīd al-Dīn Faḍl Allāh, Firdaws al-Tawārīkh by Abrqūhī, and Taʾrīkh-i Alfī by Aḥmad ibn Naṣr Allāh Tattavī (as cited in Qazvīnī’s annotations on the Chahār Maqāla). Khayyām was born sometime between 230 and 440 A.H. The details of his youth and education remain uncertain, yet it is established that he became one of the leading figures of his era in philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. In 467 A.H., Sultan Malikshāh Seljuk appointed Khayyām, along with several other renowned scholars of the time—including Abū al-Muẓaffar Isfazārī, Maymūn ibn Najīb Wāsiṭī, and Abū al-ʿAbbās Lawkarī—to reform the calendar. It has been written that: *“Khayyām’s theories on calendar reform were even more accurate than the present European Gregorian calendar, for while the Gregorian calendar errs by one day in 2,320 years, Khayyām’s calendar errs by one day only in 3,770 years.” In collaboration with Abū al-Fatḥ ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Manṣūr al-Khāzinī and other scholars, Khayyām organized an observatory for Malikshāh, on which great sums were spent; it remained active until 485 A.H., the year of Malikshāh’s death, after which it was abandoned. The treatises Khayyām left in mathematics all bear testimony to his mastery and expertise in the field. As mentioned, he was also among the eminent physicians of his time; it is recorded that when Sanjar, the son of Malikshāh, contracted smallpox, Khayyām was appointed to treat him. Khayyām enjoyed respect among kings, dignitaries, and scholars of his era, and maintained relations with Seljuk rulers such as Malikshāh and Khwāja Niẓām al-Mulk, as well as intellectuals like al-Ghazālī. Yet Khayyām’s extraordinary fame in the modern era—across the East, Europe, and America—is primarily due to the philosophical quatrains attributed to him. His mathematical works (such as Al-Jabr wa al-Muqābala, Fi Sharḥ mā Ashkala min Muṣādarāt Kitāb Uqlīdis, and his solution of an algebraic problem through conic sections) attest to his profound scholarship. George Sarton, the historian of science at Harvard University, in his Introduction to the History of Science, writes: “ʿUmar Khayyām was one of the greatest mathematicians of the Middle Ages. His book on algebra contains both algebraic and geometric solutions to quadratic equations, an admirable classification of linear, quadratic, and cubic equations, and systematic investigations into their complete and incomplete solutions. This treatise is one of the most remarkable works of medieval mathematics, and perhaps the most remarkable of all in this science.”

Poetry was not Khayyām’s profession, yet at times he expressed his ideas and reflections in wise quatrains. Some of his writings were lost through the vicissitudes of history. Contrary to popular misconceptions that portray him as a libertine or wine-worshipper—labels spread either through misinterpretation or ulterior motives—historical evidence consistently refutes such claims, instead affirming Khayyām’s profound intellect and scholarship. The late Nakhjavānī wrote: “Such careless notions lead Iranians toward stagnation, lethargy, and indifference. We must claim Khayyām for Iran, not Iran for Khayyām.” From the nineteenth century onward, Ḥakīm ʿUmar Khayyām rose to international fame, and without exaggeration may be regarded as the most celebrated Persian poet in the Western world. This renown began with Edward FitzGerald’s (England, 1809) translations of Khayyām’s poetry into English. Using a manuscript in Oxford’s Bodleian Library, dated 865 A.H. and containing 101 quatrains, FitzGerald published his first translation in 1859, thus introducing Khayyām to Europe and America.

The English Reception of Khayyām’s Poetry

The reception of these poems in England was such that many people committed numerous verses to memory. Their expressions became proverbial, entered into common sayings, and words such as “jug, cupbearer, nightingale, Parvin (the Pleiades), caravanserai, Jamshid, and Bahrām”—all of which FitzGerald retained verbatim in his translation—became familiar to English speakers. The earliest source that mentions Khayyām’s grave is Niẓāmī ʿArūḍī’s Chahār Maqāla, written in 506 A.H., which, in addition to recording the precise location of the tomb, states: “In the midst of a convivial gathering, I heard from Ḥujjat al-Ḥaqq ʿUmar that he said: ‘My grave shall be in a place where every spring the north wind scatters flowers upon me.’ This remark impressed me, for I knew he would not utter such words idly. When in the year 530 I arrived in Nishapur, several years had already passed since that great man had veiled his face beneath the soil.” (Baḥr al-ʿUlūmī, 1976). After the death of Ḥakīm ʿUmar Khayyām, his body was interred in the Ḥīra cemetery of Nishapur, near the shrine of Imāmzāda Muḥammad Maḥrūq. With the Mongol invasion of Nishapur and the subsequent massacre, the city’s buildings were destroyed and its cemeteries desecrated. The shrine of Imāmzāda Maḥrūq was first rebuilt during the reign of Sulṭān Ḥusayn Bayqara. Later, in the Safavid period under Shāh Ṭahmāsp, an iwan in front of the shrine and surrounding chambers were constructed. One of these chambers, to the east of the shrine, became the site of Khayyām’s grave, which was marked by a rectangular tomb of brick and plaster placed at the center of the chamber.

As we have explained in earlier issues of Honar-e Memari, in 1934 (1313 A.H. Solar), during the millennial celebrations of Ferdowsī in Tehran and Ṭūs, it was anticipated that Orientalists and scholars traveling to Ṭūs would naturally pass through Nishapur and visit Khayyām’s tomb. Therefore, the Society for National Heritage resolved to construct a mausoleum for him. Due to limited time, a temporary open-air stone structure was hastily erected at the site of Khayyām’s grave chamber. The new design was the work of Karīm Ṭāherzāda Behzād and was located east of the shrine of Imāmzāda Maḥrūq beneath the open sky. It consisted of two iwans, one upper and one lower, and a low stone wall of Khallaj stone from Mashhad surrounding the grave site.

Upon the grave—situated a few meters away from the shrine wall—a column was placed, inscribed with quatrains by Malek al-Shoʿarāʾ Bahār:

Sit upon Khayyām’s soil and seek delight,

For one brief moment flee the sorrows of time.

If you would know the date of this shrine’s foundation,

Seek joy of heart and faith from Khayyām’s tomb.

Concerning this visit (the visit of Ferdowsī Millennium guests to Khayyām’s tomb), Dr. Ṣedīq, himself part of the caravan, wrote:

“The Orientalists gradually arrived, entered the garden, and were delighted by its pleasant scenery, praising Iranian taste and artistry until they reached Khayyām’s grave and gathered around it. Those who knew Persian recited the above quatrain, translating it for the others. The extraordinary eagerness of the Orientalists to visit Khayyām led them to deep reflection and meditation. Suddenly, Sir Denison Ross, who had written a study on Khayyām, loudly recited from memory the following quatrain from FitzGerald’s English translation:

Whether life’s cup be sweet or bitter, it passes away.

When the goblet is full, what matters Nishapur or Balkh?

Drink wine! For after you and me, the moon

Will rise and set from new month to full countless times.

Shortly thereafter, Drinkwater recited another quatrain from FitzGerald’s translation, in a most melodious and moving voice:

When friends gather together at the appointed time,

Let them rejoice in the beauty of one another.

When the cupbearer raises the Magian wine in hand,

May he remember poor me in his prayers.

Concerning this visit (the visit of Ferdowsī Millennium guests to Khayyām’s tomb), Dr. Ṣedīq, himself part of the caravan, wrote:

“The Orientalists gradually arrived, entered the garden, and were delighted by its pleasant scenery, praising Iranian taste and artistry until they reached Khayyām’s grave and gathered around it. Those who knew Persian recited the above quatrain, translating it for the others. The extraordinary eagerness of the Orientalists to visit Khayyām led them to deep reflection and meditation. Upon hearing this quatrain, one of the guests was so overcome with emotion that he burst into tears, and naturally the others followed suit, so that a state overtook the gathering that words cannot describe.” (Baḥr al-ʿUlūmī, 1976).

The New Mausoleum of Khayyām

From the moment Khayyām’s mausoleum was inaugurated in 1934, admirers and connoisseurs alike considered it unworthy of his stature. Particularly after the construction of the mausoleums of Avicenna and Saʿdī, and the initiation of Nader’s tomb, the Society for National Heritage was continually petitioned to erect a monument befitting Khayyām’s rank. In 1954, Mr. Fāẓelī, the head of education in Nishapur, repeatedly sent reports and letters to the Governor of Khorasan, the Ministry of Culture, and the Society for National Heritage, conveying the requests of the people and pilgrims for a proper mausoleum. In July 1956, Governor Rām of Khorasan formally requested the Society to prepare plans for the tombs of Khayyām and ʿAṭṭār. Subsequently, Reżā Jaʿfarī, then Governor and head of the Society’s Khorasan branch, wrote to the Society that during his visit to Nishapur, he had inspected Khayyām’s tomb and found it utterly unworthy of the sage’s stature, urging immediate action for reconstruction. By November 1956, the Society informed the Governor that plans were already underway to design suitable monuments for Khayyām, ʿAṭṭār, and Kamāl al-Mulk, and that the final designs would be sent once completed. In August 1956, the Society wrote to Engineer Houshang Seyhoun, professor at the University of Tehran, stating: “According to reports, the present condition of Khayyām’s tomb is most unsatisfactory. The Society intends to take action. Please prepare the necessary design and collaborate with us.” In December of the same year, another letter reiterated that since a mausoleum befitting Khayyām and Kamāl al-Mulk was to be built, Seyhoun should prepare a design worthy of their stature. A month later, Engineers Seyhoun and Hossein Jowdat visited Khayyām’s tomb in Nishapur and reported: “…As you have observed, the present site of the tomb is attached to the shrine of Imāmzāda Maḥrūq, and any construction there would deprive Khayyām’s mausoleum of independence and prominence. It is therefore essential to designate a new site within the same complex. After due study, the location was determined, and preliminary sketches prepared, so that upon approval, detailed plans and cost estimates may be presented.” (Baḥr al-ʿUlūmī, 1976) It should be noted that the garden of Imāmzāda Muḥammad Maḥrūq, constructed during the Safavid period on the site of the Ḥīra cemetery, covers approximately 43,200 square meters, rectangular in shape, 240 meters in length and 180 meters in width, oriented north–south, with the shrine situated at its center. The site Seyhoun selected for Khayyām’s new mausoleum, where the monument now stands, is located in the northeastern corner of the garden. The Society sent Seyhoun’s design to the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Tehran on May 27, 1958, requesting a thorough review. On June 7, 1958, Professor Moḥsen Foroughi, Dean of the Faculty, responded that the design, prepared by Professor Houshang Seyhoun and accompanied by models, had been carefully examined. Given that the design drew extensively upon the principles and aesthetics of Iranian architecture, the plan was deemed entirely fitting for the mausoleum of the great sage of Iran. Thereafter, the Society’s board held multiple sessions to discuss the design and construction of the mausoleum in detail. On several occasions, Khorasan’s parliamentary representatives, including Mr. Mūʾayyad Sābetī and Mr. Nabavī, were also in attendance.

The Contract with Engineer Houshang Seyhoun and the Construction of Khayyām’s Mausoleum

On March 15, 1959 (24 Esfand 1337), a contract consisting of 13 articles was signed between the Society for National Heritage and Engineer Houshang Seyhoun. According to this agreement, Seyhoun undertook to design the plans for the mausoleums of Khayyām and Kamāl al-Mulk, together with the subsidiary buildings, landscaping, water features, and the street linking the two monuments, and to supervise their execution. For the preparation of designs, technical calculations, and supervision, he was to be paid the equivalent of five percent of the total cost of the works. Under this contract, Engineer Seyhoun committed to preparing and gradually delivering the preliminary, final, and detailed architectural drawings of Khayyām’s memorial. These were to include the main structure, the surrounding terraces, fountains, and subsidiary buildings. The final designs, based on the model and preliminary scheme already approved by the University of Tehran and the Society, were to be delivered within three months of signing, while the detailed plans would be submitted progressively thereafter. Furthermore, Seyhoun was assigned full responsibility for supervising construction. He was obliged to appoint a qualified civil engineer, experienced in site work, as his permanent representative at the construction site, with the salary to be paid by Seyhoun himself. In addition, Seyhoun personally was required to inspect and supervise the works on site every two months and to submit written progress reports to the Society. He also agreed to coordinate the work schedule with the contractor to ensure that the building would be completed in time for the inauguration of Nader’s mausoleum.

In a report submitted to the Society, Engineers Seyhoun and Jowdat described some of the planned features of Khayyām’s mausoleum:

“The structural skeleton will be of metal, clad with aluminum. The roof will incorporate thick, colored glass, and the wall surfaces will be decorated inside and out with tilework. The foundations will be in reinforced concrete, with granite steps, platforms, and fountains. The walls adjacent to the fountains will be faced with travertine, and the tombstone itself will be of black stone from Mashhad. The mausoleum will be situated at the eastern end of the garden’s central axis, at the beginning of a change in level, thereby making full use of the vista of the Imāmzāda Maḥrūq garden.”

The Contractor

On December 13, 1958 (22 Azar 1337), the construction company KAJT informed the Society for National Heritage:

“With full awareness of Engineer Houshang Seyhoun’s requirements for Khayyām’s mausoleum—that it be executed in fine concrete, flawless in every respect, and acceptable to both the supervising engineer and the Society—our company is prepared to undertake this project. Should the employment of foreign experts and workers prove necessary, we will proceed with their recruitment, subject to the approval of the Society and Engineer Seyhoun, in order to complete the work in a manner worthy of acceptance.” (Baḥr al-ʿUlūmī, 1976)

Subsequently, Seyhoun and Jowdat wrote to the Society:

“As you know, the preliminary design for Khayyām’s mausoleum was based on a metal framework to be clad in aluminum. However, consultations with specialists revealed that aluminum sheathing would have undesirable effects on the metal due to chemical interactions. It was therefore decided that the structure should be executed in fine concrete, and that the height of the mausoleum should be increased from 12 meters to 22 meters, thereby giving it greater grandeur. Since commissioning foreign firms directly would entail considerable expense, and since the KAJT company has declared its willingness to execute the construction at its own responsibility, employing foreign specialists if necessary, we believe it best to entrust the project to this company. In the construction of Nader’s mausoleum, KAJT demonstrated both its competence and its commitment to quality, proving itself to be a contractor of reliability and precision. Given the technical requirements of Khayyām’s mausoleum, which demand the utmost care in durability and craftsmanship, it is advisable to assign the project to this company. Even the slightest negligence here could, as with Ferdowsī’s mausoleum, lead to regret.”

Engineers Moḥsen Foroughi, Ṣādeq, Seyhoun, and Jowdat also prepared an official statement for the Society:

“The construction of Khayyām’s mausoleum—consisting of a structural skeleton in metal and concrete, with stone facing and tilework—cannot be regarded as an ordinary building for which external analogies exist. Though delicate in appearance, it must be executed with extreme precision to ensure both durability and aesthetic excellence. Because of the refinement of the operations required, the work must be entrusted to a contractor who not only has a strong record in major projects but has also demonstrated skill in works of a comparable nature.” (Baḥr al-ʿUlūmī, 1976). KAJT, equipped with the necessary tools and with experience in major projects, had already, in the construction of Nader Shah’s mausoleum, proven its reliability and professionalism. With the approval of Seyhoun as supervising architect and the satisfaction of the Society, KAJT was therefore entrusted with the execution of Khayyām’s mausoleum. It was further noted that, given the unique technical operations involved, certain items of work might not correspond to the unit prices of earlier contracts, and that new, appropriate pricing should be established where necessary.

Board Decisions and Commencement of Construction

At the meeting of the Board of Directors of the Society for National Heritage held on December 23, 1958 (2 Dey 1337), and in view of the proven record of the KAJT Company in the construction of Nader’s mausoleum, the contents of the aforementioned reports, and the exceptional requirements of Khayyām’s mausoleum, it was resolved that—so as not to delay this important undertaking—the execution of the project be entrusted to KAJT. The company was also required to honor the same discount it had granted in the construction of Nader’s mausoleum. For, even if the project were to be put out to tender, the likelihood of securing a discount greater than that achieved in the Nader project was remote; and any new contractor would still require time to prove his competence. Accordingly, on December 28, 1958 (7 Dey 1337), the Society wrote to KAJT informing them of its acceptance of their proposal to build Khayyām’s mausoleum under the stated conditions. On the same day, a letter was also addressed to Dr. Mehrān, Minister of Culture, requesting that the General Directorate of Endowments grant the Society’s representatives and the contractor access to that part of the Imāmzāda Maḥrūq garden designated for the mausoleum, and instructing the relevant offices in Nishapur to give their fullest cooperation in this important matter.

The Laying of the Foundation Stone

At 5 p.m. on Tuesday, May 18, 1959 (28 Ordībehesht 1338), in the presence of the Governor of Khorasan, several members of the provincial Society for National Heritage, local officials, and notables of Nishapur, the foundation stone of Khayyām’s mausoleum was ceremonially laid. In his opening address, Mr. Barahmand, governor of Nishapur, declared:

“In late 1958, General Sepahbod Āqāvalli, chairman of the Society’s board, accompanied by a number of engineers and Mr. ʿElmi, director of historic monuments, visited Nishapur. They inspected the tomb of ʿAṭṭār and the grave of the late painter Muḥammad Ghaffārī (Kamāl al-Mulk). Upon their return to Tehran, the contract for the design of Khayyām’s mausoleum was concluded with Engineer Seyhoun, and the construction was entrusted to the KAJT Company. The excavation of the site has now been completed, and today we lay the first stone of the new building. Restoration of the mausoleum of Shaykh Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār has also begun, and plans for Kamāl al-Mulk’s tomb are being prepared. The required stones for piers, inscriptions, and dadoes—both interior and exterior—are being prepared in Mashhad and transported to Nishapur. A group of master tile-makers in Mashhad is producing fine tiles for the mausoleum’s façades. A comprehensive plan has been drawn for a wide, tree-lined avenue to connect the two mausoleums of Khayyām and ʿAṭṭār, and construction of this thoroughfare has already begun. As much of the land was privately owned, Mr. Ebrāhīm Saʿīdī, member of the Society in Nishapur, purchased the plots on its behalf. To provide water for the needs of the two mausoleums, for irrigation, and for gardening, a contract for drilling a deep well was concluded with a Khorasan company, of which seventy meters has already been dug. In the course of these works, major repairs to the historic shrine of Imāmzāda Maḥrūq, situated in the same garden, will also be undertaken. Furthermore, the Society has entered into agreements with scholars and authors for the publication of some of the works of Khayyām and ʿAṭṭār, as well as new studies on these two great figures.”

At the conclusion of this address, Mr. Reżā Jaʿfarī, Governor of Khorasan and president of the provincial branch of the Society, placed a commemorative plaque within the foundations, inscribed with the name of the Society and the date (28 Ordībehesht 1338).

Progress of Construction

Thus, from early 1959, the construction of Khayyām’s mausoleum formally began, and much of the foundational work was completed in the same year. This included: excavation and concrete foundations for the carved stone perimeter walls, construction of portions of the entrance avenue’s stone walls, installation of granite steps at the entrance and throughout the garden, initial works on the reception hall, library, and office, erection of part of the steel framework of the mausoleum, preparation and carving of cladding stones, and procurement of granite for fountains and water features. It soon became clear, however, that the intended use of fine reinforced concrete was technically impracticable in Iran. It was therefore proposed that the lattice tower of the mausoleum be built with a steel skeleton, clad externally with finely cut stone and decorated with tilework. Since this revision entailed higher costs and longer construction time, the matter was referred to the Society’s board of founders, who, after on-site inspections in Nishapur and Mashhad in December 1959, approved the revised plan: a lattice tower of steel framework, clad in stone, with rich tile decorations. Construction continued through 1960 and 1961. Among the final works completed in 1961 were: installation of stone cladding; preparation and mounting of eight large lozenge-shaped mosaic panels inscribed in monumental taʿlīq script with Khayyām’s quatrains, interwoven with arabesque floral motifs, on both interior and exterior façades; mosaic tilework for the inner dome; stone inlay on the dome’s exterior; completion of granite fountains around the courtyard; construction of stone walls along the avenue opposite the mausoleum; retaining walls in front of the elevated platform facing Imāmzāda Maḥrūq; installation of railings; covering the fountain basins with irregular granite slabs; asphalting of the entrance and southern roads; completion of the walkways around the guesthouse, office, and library; landscaping for lawns and flowerbeds; four sets of stone steps along the central axis; and furnishing of the guesthouse, office, and library with carpets, furniture, and bedding. Thus, by early 1962 (1341 A.H. Solar), construction of Khayyām’s mausoleum was completed. This architectural landmark was officially registered in the National Heritage List on December 9, 1975 (18 Azar 1354) under number 12/1175.

Transfer of Khayyām’s Remains

In April 1962, as construction neared completion, the Society wrote to the governor of Nishapur, head of the provincial Society, and Mr. Ebrāhīm Saʿīdī, member of the Society, stating:

“After removal of the remains from Khayyām’s former tomb, the bones must, with utmost care and in the presence of representatives of the Society and competent authorities, be documented through precise photography, then placed in a casket. Following proper religious rites, the casket shall be interred in the new mausoleum in accordance with religious customs. The representative of the KAJT company should be informed in advance so that the burial site is prepared.” (Baḥr al-ʿUlūmī, 1976). On May 19, 1962 (29 Ordībehesht 1341), in the presence of General Sepahbod Āqāvalli, Dr. Ṣedīq, General Fīrūz, Ḥasan Nabavī, Dr. ʿAlī-Akbar Shahābī (Director-General of Endowments), and a group of notables, officials, and members of the Nishapur branch of the Society, the remains—encased in a reliquary—were solemnly transferred to the new mausoleum after religious ceremonies.

Remnants of the Former Mausoleum

In March 1962 (Esfand 1340), Engineers Seyhoun and Jowdat reported to the Society for National Heritage that the municipality of Nishapur intended to transfer the remains of Khayyām’s former mausoleum to a square opposite the Khayyām High School. A memorandum was prepared and attached, stating:

“With the erection of the grand memorial to Khayyām in the garden of Imāmzāda Maḥrūq, it was deemed necessary to relocate the structure of the former mausoleum to a more suitable site. In a meeting attended by the head of the city council, Mojtahedī (acting mayor), ʿAbdullāh Saʿīdī (former deputy of Nishapur), Ḥasan Jowdat, Engineer Seyhoun, and Engineer Konstantin, it was decided that the old monument should be transferred to one of the city squares. As construction of the new mausoleum will be completed by late April 1962, the relocation should be accomplished by that date.” (Baḥr al-ʿUlūmī, 1976)

The Architecture of the Mausoleum

Faramarz Pārsi writes:

“With the nationalization of mausoleum building, two distinct paths emerged. One concerned the shrines of Imāmzādas, built through the endowments of devotees and shaped by the language of traditional religious architecture, enriched over time with elaborate embellishments such as mirrorwork. The other consisted of the tombs of poets, writers, and scholars, constructed with state budgets. The latter path, beginning with the mausoleums of Ḥāfeẓ and Ferdowsī under Reżā Shāh, combined elements of Iranian architecture with Western neoclassicism. With the entry of architects such as Foroughi and later Seyhoun, however, a new tendency emerged—one that can be said to have profoundly influenced the architecture of the late Pahlavi era. These architects, modernists at heart yet enamored of Iranian tradition, fused indigenous motifs with the individualism and innovation of modern architecture. A distinguishing feature of these mausoleums was their reflection of the honoree’s life and personality—whether as mathematician, poet, or philosopher—something previously absent in funerary architecture. Formally, while inspired by the historic tower-tombs, they employed stone and tile as their principal materials, often incorporating karbandi (geometric vaulting) with a modern reinterpretation.” The mausoleum of ʿUmar Khayyām is one of the finest examples of this genre. The renowned journal Japan Architect, in its January 1963 issue, praised the monument for its design and artistic qualities. The mausoleum stands in a vast garden outside Nishapur, two kilometers west of which lies another garden containing the tomb of the great mystic ʿAṭṭār. Initially, Khayyām’s grave was contiguous with Imāmzāda Maḥrūq, but the new mausoleum was aligned along an axis toward ʿAṭṭār’s tomb, with a connecting road constructed between the two sites. In accordance with Khayyām’s own testament, Houshang Seyhoun chose a site within the garden set three meters lower than the surrounding apricot trees, so that every spring blossoms would fall upon the grave. Seyhoun himself remarked that he had relocated the burial sites of seven figures: Khayyām, ʿĀref Qazvīnī, Abū Saʿīd Dukhdūk, Nāder Shāh Afshār, Colonel Moḥammad-Taqī Khān Pesyān, Avicenna, and Ferdowsī. The design of Khayyām’s mausoleum reflects his multifaceted identity as scientist, astronomer, philosopher, mathematician, and poet. Its architecture emphasizes geometry and astronomy, while drawing inspiration from the Persian garden. Around the central tower are seven triangular granite fountains, symbolizing the heavens and the stars, arranged in decagons and conical lattice vaults adorned with mosaic faience in flowing taʿlīq script. All of this speaks to Seyhoun’s profound and poetic interpretation of Khayyām’s genius. The fountains, set in a semicircle around the granite tower, with their triangular recesses and projections, evoke the form of a tent (khayma in Persian). The name “Khayyām,” meaning tentmaker, alludes to his father’s profession, and Seyhoun incorporated this motif throughout the design to echo Khayyām’s identity in the very waters and stone of his memorial.

Amīr Bānī-Masʿūd, in Contemporary Architecture of Iran, recounts Seyhoun’s own words about the design:

“Over thirty years ago, when the Society for National Heritage decided to erect a suitable monument for Khayyām, I was entrusted with the task. Since it was impossible to build a large, prominent structure adjacent to the shrine of Imāmzāda Maḥrūq, I created a transverse axis in the garden, perpendicular to the main one, and placed the entrance to Khayyām’s mausoleum there. This axis also aligned with ʿAṭṭār’s garden, so that a new road linked the two. The circular base was divided into ten segments at five-meter intervals, so that the tower rests on ten foundations. The number ten, the first two-digit number, is fundamental in mathematics. From each base, two diagonal ribs rise and intersect in space, forming the overall volume of the tower. As the ribs ascend in a spiral, their crossings create complex geometries. At the uppermost point, the interlacing ribs generate overlapping star-shapes through which the blue sky of Nishapur appears, culminating in a five-pointed star—an explicit reference to Khayyām’s identity as an astronomer. The intersections form ten large lozenges, each filled with tilework. The best adornment was Khayyām’s own quatrains, inscribed in abstract, overlapping shekasteh script reminiscent of master calligraphers such as Mīr ʿEmād, transformed into mosaic ornament. The granite pools, lined with turquoise tiles, together form the seven-pointed star, signifying the seven heavens and celestial domes of Khayyām’s science, while also recalling the form of a tent. The ensemble, with its lofty trees and open-air setting, is profoundly poetic—exactly as Khayyām himself wished, so that in springtime, blossoms would shower his grave.” The lower lozenges of the tower are filled with elaborate *mosaic faience*: on the outer faces, pairs of quatrains inscribed in flowing, broken taʿlīq script; on the inner faces, arabesques of leaves and tendrils unfurl across the ceramic surfaces.

Design Details and Symbolism in Seyhoun’s Mausoleum for Khayyām

In Houshang Seyhoun’s design, the central lozenges of the structure are left open, framed with slender, translucent stones, while their interior surfaces on both sides are adorned with intricate mosaic faience. These shimmering inlays lend the building a striking poetic quality, directly alluding to Khayyām’s identity as a poet. It is worth noting that—unlike the modern innovation of calligraphic painting—the technique of stone-framed tilework has historic precedents. Among the most notable examples are the Darv-e Imām monument in Isfahan (880 A.H.), built over the shrines of Imāmzādas Ibrāhīm and Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn, where exquisite mosaic faience framed in marble survives, and the Mowlānā Mosque in Taybād, from the era of Shāhrokh Tīmūr, as well as the famed Blue Mosque of Tabriz (870 A.H.), where stone and tile are artfully interwoven into harmonious compositions of unrivalled delicacy. In Khayyām’s mausoleum, stones more durable than marble, yet equally rich in color and luminosity, were chosen to harmonize with the mosaic tiles. The triangular and lozenge-shaped forms that articulate the tenfold geometry of the structure, combined with the circular base and vertical curvature of the walls, produce subtle convexities throughout. Each stone was carved to follow these curvatures with precision. The underside of the dome is covered in mosaic tilework, while the exterior of the dome gleams with intricate stone marquetry. Around the mausoleum stand seven graceful stone “tents,” each sheltering a turquoise-tiled pool beneath, with water cascading into them to create scenes of extraordinary beauty. Behind the tower, in the outer courtyard, geometric pyramid-like fountains carved from massive granite boulders extend the celestial motif. Twenty of Khayyām’s most celebrated quatrains are inscribed on the ten external lozenge panels in monumental taʿlīq script. These were carefully selected by Master Jalāl al-Dīn Homāʾī at the request of the Society for National Heritage, transcribed by calligrapher Morteżā ʿAbd al-Rasūlī, and realized in mosaic tiles by master craftsman Moṣṭafā Ṭabāṭabāʾī of Isfahan, together with his apprentices.

Critical Reflections on the Architecture

Architect and researcher Moḥsen Akbarzādeh observes:

“Though one could, by genealogical classification, call Khayyām’s mausoleum a dome articulated with turrets and without a cap, one must nevertheless concede its uniqueness within tradition—uniqueness achieved precisely through continuity. This is not the familiar ‘modernization’ of tradition, whereby a modern building is seasoned with borrowed traditional elements, nor the reverse, where a traditional typology such as a dome is reinterpreted with modern gestures. In Khayyām’s mausoleum, tradition itself is rendered contemporaneous. The use of calligraphy, the geometric segmentation of the turrets, the openwork that exposes the sky, the non-loadbearing latticework, even the manner in which the dome joins the ground—none of these are mere modernization. Rather, they represent the fulfillment of a longstanding desire of Iranian architects: to extend the dome’s structural pattern beyond the limits of material constraint, here from the four supports of a chahārtāq to a decagonal base. The continuity of geometry in the landscaping echoes the extension of the dome chamber into the surrounding arcades of classical Persian ensembles. Yet the composition as a whole bears the mark of modern architectural pedagogy.”

Architectural historian Elaheh Najafī adds:

“The mausoleum of Ḥakīm ʿUmar Khayyām and the city of Nishapur are mutually indebted to one another; each has safeguarded the other’s memory. For nearly six decades, Khayyām’s tomb has been central to Nishapur’s cultural identity and its tourism industry—so much so that the first image evoked by the name ‘Nishapur’ is often the mausoleum itself. Its location, slightly removed from the city’s bustle and set within a garden, has shielded it from environmental degradation, in contrast with monuments like Avicenna’s tomb. Within this ideal setting, Seyhoun—the father of modern Iranian architecture—employed masterful techniques and intelligent contrasts that amplify the monument’s allure: The monumental and godlike dimensions of the structure coexist with a sense of intimacy and humility, embodying both grandeur and humanity—qualities also debated in Khayyām’s personality. A steel skeleton and concrete framework, combined with modular openings and transparent vistas toward the sky and garden, create a structure that, despite its scale, appears light, fluid, and permeable to nature. All facets of Khayyām’s intellectual life—mathematics, astronomy, poetry, and philosophy—find architectural expression. Numbers, geometry, constellations, and verses converge into a single coherent language, inviting the observer to probe its mysteries, much as Khayyām himself was known for his probing genius. The consistency of concept, from the tombstone to the overall landscaping, ensures unity and harmony. Repeated motifs, carefully orchestrated compositions, and fidelity to the guiding inspiration produce an aesthetic coherence that is both poetic and rigorous. Finally, the monument appears to emerge organically from its site, rooted in the very earth of Nishapur—an integration of architecture and landscape achieved with exceptional mastery by Seyhoun.”

Tent-like Design and Site Context

The tent-like conception of the mausoleum (inspired by Khayyām’s very name and life), together with its ensemble of turquoise pools, granite pyramids, and flowing channels, all arranged around the circular center of the tower, creates the impression of a great pavilion. These elements encircle the monument as though it were draped in a tent, spreading across the garden’s ground like a garment, and absorbing the greenery of the orchard into its embrace. The mausoleum of Khayyām, beyond being an architectural jewel of its time, thus stands as a valuable model for architects: a lesson in the art of seeing, in conceptual ideation, in weaving together science, art, and nature, in comprehensive analysis of a design problem, and in ultimately achieving a coherent and poetic architectural response.

The Garden and Setting of the Mausoleum

As mentioned earlier, the mausoleum is situated in the northeastern corner of the garden of Imāmzāda Muḥammad Maḥrūq. The principal north–south avenue of the garden, lined with ancient trees, defines the main axis and vista of the shrine. Khayyām’s mausoleum rises to the northeast of this avenue, at a short distance from it, with a new westward axis leading to the garden’s entrance on the western side. Because of the differences in elevation within the garden, the floor of the main avenue and the base level of Khayyām’s mausoleum lie lower than the precinct of the Imāmzāda shrine and its forecourt. This ensures that the shrine, as a historic and religious monument, retains visual primacy. Within this topography, Khayyām’s mausoleum, set in the corner of the enclosure, acquires a balanced presence: on one side bounded by a stone wall, on the other opened by steps rising to the fountains and terraces around the tower. The platform above the fountains, level with the higher ground of the garden, has been planted with weeping willows, whose branches, spreading across the tower’s volume, heighten the verdancy and freshness of the setting. The tall retaining walls of the platform are built of stone, while between the terrace and the shrine of Imāmzāda Maḥrūq, a series of low, continuous railings has been installed to subtly demarcate the two precincts.

The Garden and Surroundings

The entire grounds of Khayyām’s mausoleum are carpeted with lawns, flowers, and greenery. Walkways have been constructed around the guesthouse, the office, and the library, while borders and flowerbeds line the garden’s avenues. The entrance and southern roads of the complex have been asphalted, and the walls of the avenue facing the mausoleum have been faced with stone. Extensive repairs and restorations carried out at the shrine of Imāmzāda Maḥrūq have further enhanced the dignity and splendor of Khayyām’s resting place. Tall lampposts have been installed throughout the grounds, each set upon a triangular black metal base, creating a play of light and shadow across the garden. The subtle illumination, mingled with silence, lends the entire site an atmosphere of solemn majesty. In every respect, the mausoleum and its garden can be counted among the most picturesque and beautiful places in Nishapur.