پاویون ژاپن اکسپو ۹۲

پاویون ژاپن اکسپو ۹۲

مکان : سویا (سویا/سویل)، اسپانیا

مساحت سایت : ۵۶۶۰.۳ مترمربع

زیربنا : ۵۶۶۰.۳ مترمربع

نوع بنا : پاویون

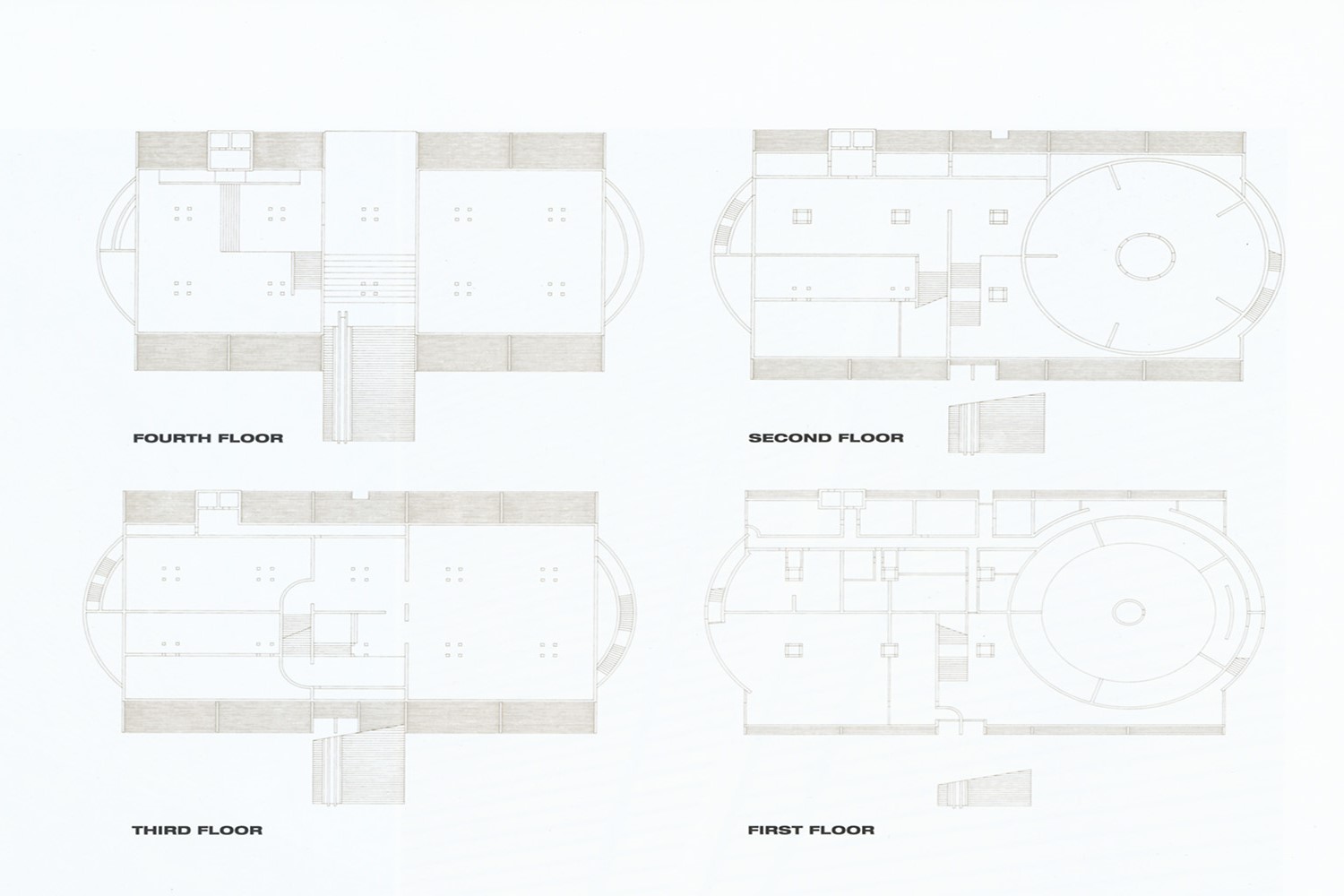

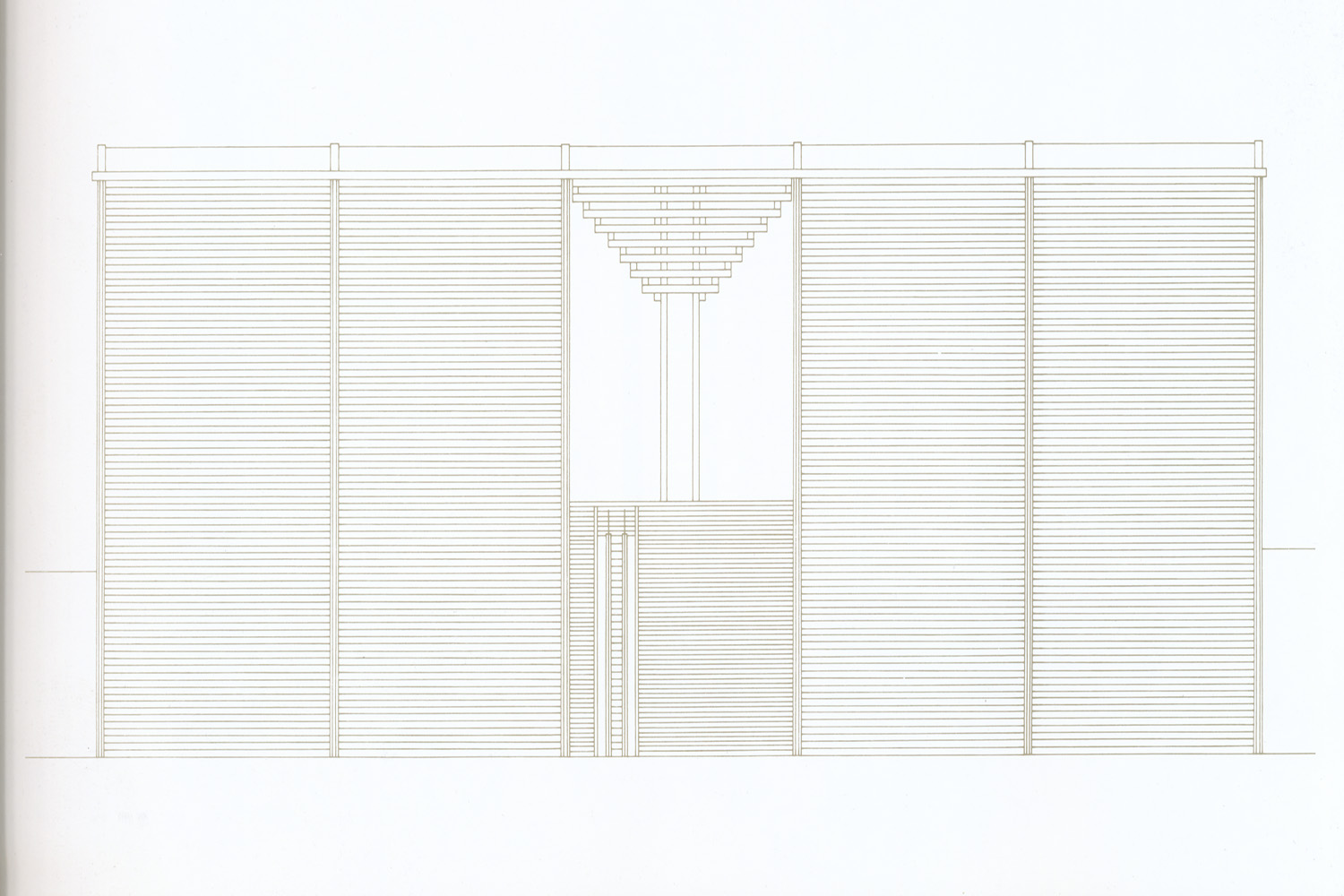

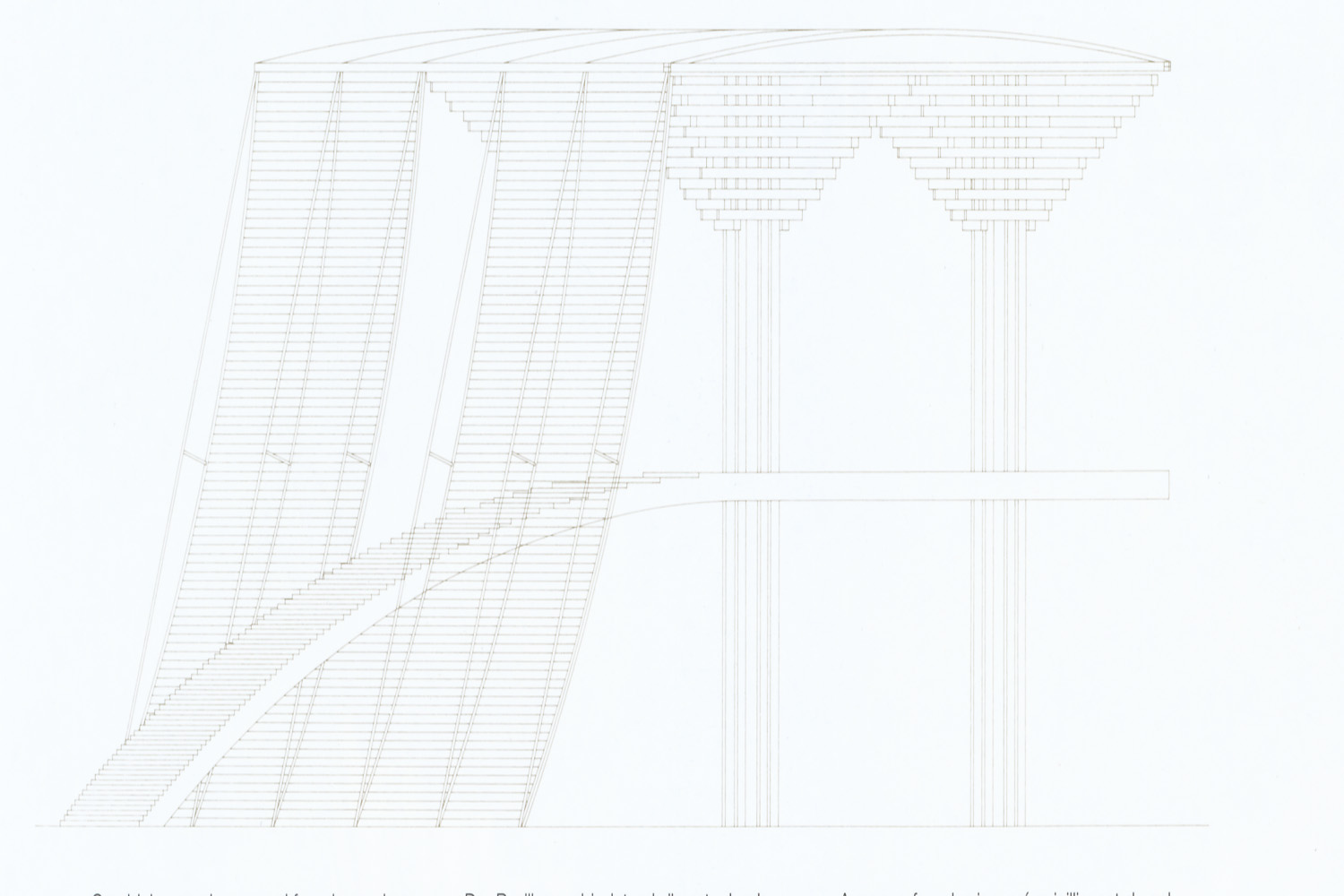

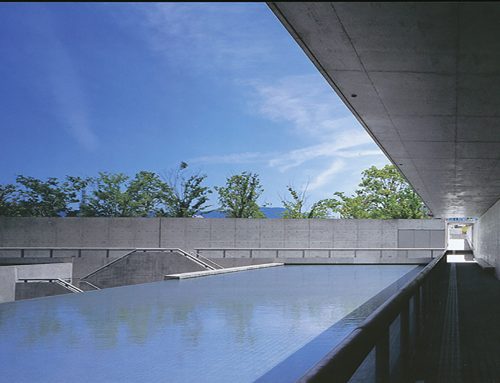

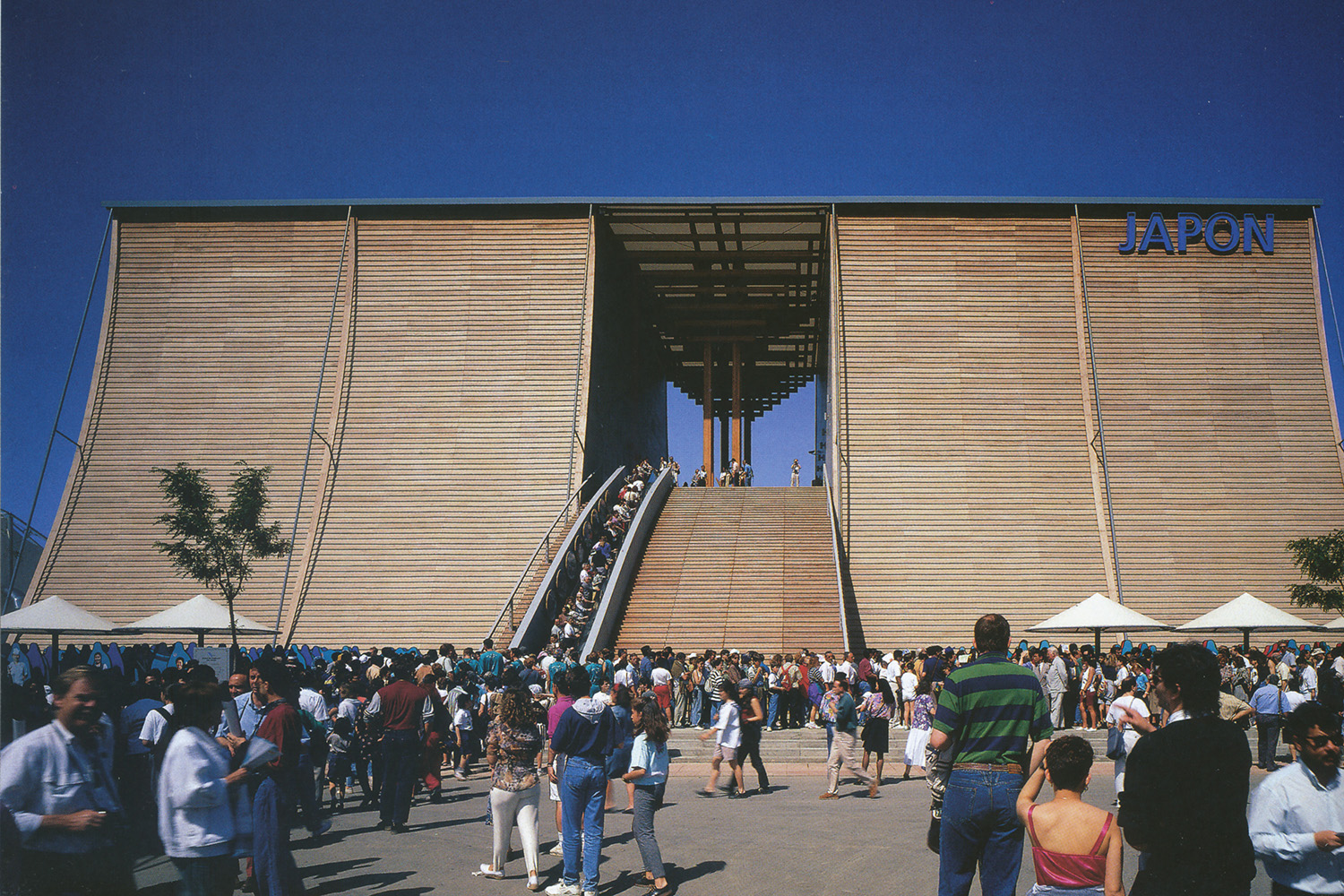

در نخستین تجربهٔ تادائو آندو در عرصهٔ معماری چوبی در مقیاس بزرگ، او از مهارت صنعتگران ژاپنی و همچنین تاریخ طراحی معابد در سرزمین خود بهره گرفت. تصویر بالا: این اسکیس توسط معمار، حجمهای اصلی را تنها با چند خط ساده مشخص میکند. این سازهٔ فوقالعاده، که یکی از بزرگترین ساختمانهای چوبی جهان به شمار میرفت، ۶۰ متر عرض، ۴۰ متر عمق و در بلندترین نقطهٔ خود ۲۵ متر ارتفاع داشت. با ترکیب چوبِ پرداختنشده –یکی از مصالح رایج ساختوساز در ژاپن–، پلی ورودی به شکل طبل ژاپنی (تایکو–باشی)، و عناصری مدرن مانند سقف نیمهشفاف کنترلکنندهٔ نور، پاویون ژاپن برای اکسپو ۹۲ آمیزهای موفق از بهترینهای شرق و غرب بود. با سکوِ ورودی مرتفعی که چشمانداز رودخانهٔ «گوادالکیویر» را ارائه میکرد –همان مسیری که کریستف کلمبوس در سفر اکتشافی خود در آن حرکت کرده بود– پاویون آندو شاید فاصلهای از استفادهٔ رایج او از بتن ایجاد کرد، اما همچنان حس فضا و معماری ویژهٔ او را حفظ نمود؛ حسی که یادآور معابد ژاپنی است. طراحی این پاویون پیوند مستقیمی با «موزهٔ چوب» و همچنین آثار متأخر آندو دارد، مانند معبد «کومیو-جی» در سائیجو یا موزهٔ چوب در «نااووشیما». پاویون ژاپن، همچون دیگر بناهای چوبی مدرن، نتیجهٔ گفتوگویی میان سنت معماری چوبی ژاپن و فناوریهای نوین است. چوبهای لمینیتشدهای که در اینجا و در پروژههایی مانند کومیو-جی استفاده شدند، به معمار اجازه میدهند در مقیاسی بزرگ و با بنیانی مدرن کار کند، بیآنکه پیوند خود با گذشته را قربانی کند. گذشته از این ملاحظات، چوب لمینیتشده در این پروژه ثابت کرده که مادهای اقتصادی، بادوام و قابلبازیافت است. با ترکیب نماهای منحنی و صعودی و پلی قوسیشکل، پاویون حالوهوایی از «کشتی نوح» دارد. اما در عین حال، یادآور برخی طرحهای معابد بستهٔ ژاپنی نیز هست؛ همان فضاهایی که سنتاً برای محافظت از اشیای ارزشمند استفاده میشدند. پایین: تصویری از پاویون پس از افتتاح برای عموم. حضور یادمانی و سترگ این سازه، با ازدحام مردم در برابر آن و هنگام بالا رفتن از پل، آشکارتر میشود. بالا: دیدگاههایی از نمای منحنی و پل. پایین: نمای روبهرو. هنگامی که انحناهای مؤثر بر نمای پاویون و پل ورودی حذف میشوند، نمای روبهرو نظم هندسی بنیادی طراحی را آشکار میسازد. نگاه به سازهٔ چوبی از پایین: بخشی از مسیر حرکتی درون پاویون بازدیدکننده را در نزدیکی عناصر چوبی لمینیتشده قرار میدهد؛ عناصری که تداوم و تکامل فنون سنتی درودگری ژاپنی را به شکلی مدرن ارائه میکنند. در سمت راست: نقشههای طبقات، هندسهٔ فشرده و منظم درونی را آشکار میسازد؛ هندسهای که در پسِ شکل سیال و پوستهٔ بیرونی پاویون پنهان است.

JAPAN PAVILION EXPO ’92

Location : SEVILLE, SPAIN

Site area : 5 660.3 m²

Floor area : 5 660.3 m²

Building : PAVILION

For his first effort in large-scale wooden architecture, Tadao Ando called on the expertise of Japanese craftsmen, as well as on the history of temple design in his country. Above: This sketch by the architect defines the basic volumes with just a few strokes of the pencil. This exceptional structure, one of the largest wooden buildings in the world, was 60 metres wide, 40 metres deep and 25 metres high at its tallest point. By combining unpainted wood, one of the typical construction materials in Japan, a drum-shaped entrance bridge (taiko-bashi) and such modern elements as a translucent deflection screen roof, the Japanese Pavilion for Expo ’92 was a successful blend of the best of East and West. With its elevated entrance platform overlooking the Guadalquivir river where Christopher Columbus sailed on his voyage of discovery, Ando’s pavilion may have represented something of a departure from his more frequent use of concrete, but it does very much conserve his sense of space and architecture, something akin to Japanese temples. The design of this pavilion has a direct connection to that of the Museum of Wood, and to more recent works such as the Komyo-ji Temple in Saijo or the Museum of Wood on Naoshima. The Japan Pavilion, like the modern wooden buildings, is also the result of a dialogue between the Japanese tradition of wooden architecture and modern technology. The laminated timber used here and in Komyo-ji, for example, permits the architect to engage in work that have a large scale and a modernist basis without sacrificing design ties to the past. Beyond these considerations, laminated timber has been shown here to be an economically viable and recyclable material. Combining soaring curved facades and an arched bridge, the pavilion has something of Noah’s Ark about it. But it also recalls some of the closed temple designs seen in Japan, which are traditionally used for safeguarding precious objects. Below: A picture of the Pavilion after its opening to the public. The monumental presence of the structure becomes even more apparent with the crowds in front and going up the bridge. Above: Views of the curved facades and bridge. Below: A front elevation. Stripped of the curves that actually make up the façade and approach bridge, the elevation reveals the fundamental geometric regularity of the design. Looking up at the framing: Part of the journey through the interior brings the visitor close to the laminated timber components, a modern refinement of traditional Japanese joinery. On the right: Floor plans show the tight, orderly geometry behind the flowing outer form of the pavilion.