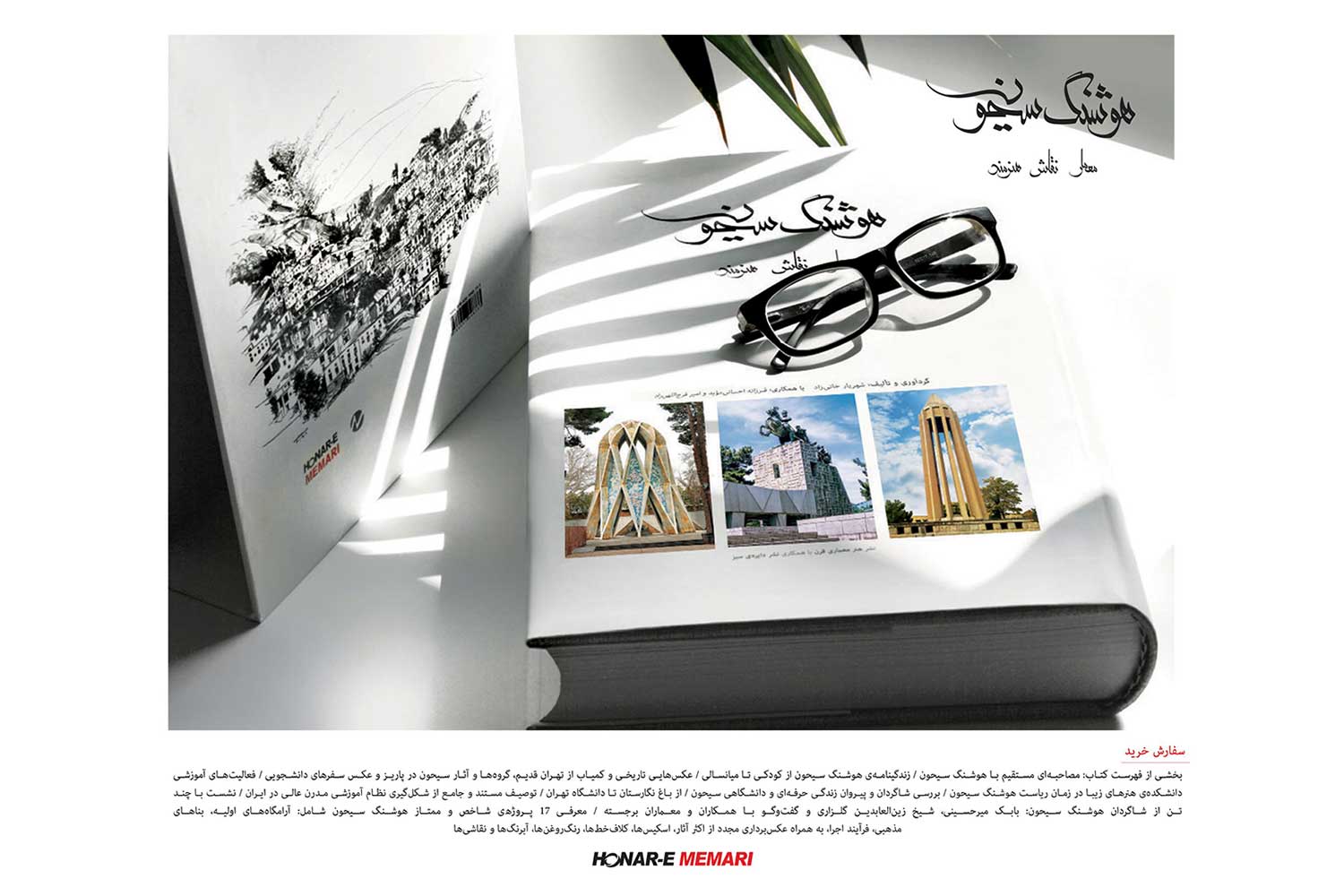

منزل و آتلیهی شخصی هوشنگ سیحون

خیابان جمهوری، تهران، 1333

Seyhoun’s Private Residence and Studio

Jomhouri Street, Tehran, 1954

منزل و آتلیهی شخصی هوشنگ سیحون، خیابان جمهوری، تهران، 1333

بزرگترین چالش طراحی یک خانه، رسیدن به یک توازن بهینه میان خواستههای زیباشناسانهی طراح و نیازهای شخصی و آمال و آرزوهای استفادهکنندگان در مورد عرصهی خصوصی زندگی روزمرهی خویش است. در عین حال که ساماندهی کلی فضاهای داخلی و خارجی متاثر از نظام فکری و ایدههای کلان طراحی معمار است، در نهایت، کاربر ساختمان باید در زیر سقف بناشده توسط معمار، احساس خوب “در خانهی خود بودن” را تجربه کنند. با این اوصاف، خانهها و اصولا بناهایی که معماران برای خویش طراحی میکنند، موضوعات بسیار جالبی هستند. اگر بپذیریم در شرایط ایدهآل، طراحی خانهها باید منتج از آنالیز دقیق و معمارانه از شخصیت ساکنان باشند، خانهای که یک معمار برای خود بنا میکند عملا بیوگرافی معمار است که در مواد و مصالح و سازمان فضایی پروژه تجلی یافته است و این بناها، بیش از هر نوع بنای دیگر در مورد خواستگاههای شخصی معماران خود، به بیننده اطلاعات میدهند.

در منزل و دفتر مهندس سیحون که با ابعاد زمین 10 × 23 متر و با حدود 440 مترمربع زیربنا در خیابان جمهوری واقع است، ترکیب سنگ و آهن به شیوهای خاص دیده میشود. وی از بهکاربردن بیپردهی مصالح واهمه نداشت، در عین حال که این جسارت، او را در ورطهی سبک بینالملل که در آن زبان معماری نوعی اختصار بصری را تولید میکند، غرق نکرده است.

نمای پروژه، کلاژ بسیار موفقی از تکنیکهای مختلف ساختوساز مدرن و فرهنگ مواد و مصالح حاکم بر آن است. بنا از خط زمین با قطعات سنگی پرداخت نشده و چهارگوش بلند میشود. بلوکهای سنگی قرارگرفته در کنار یکدیگر، کمپوزیسیون پرحجم و سنگینی را برای پایهی بنا ایجاد کردهاند.

تضاد خطوط دقیق فریمبندی پنجرهها و برشهای نادقیق قطعات سنگی، دیالوگ بصری جذابی را ایجاد میکنند. در لایهی بعدی، نمونهی موفقی از یک دیوار پوششی (Curtain Wall) دیده میشود. این پنجره بهوضوح یکی از اصول پنجگانهی معماری مدرن یا همان Ribbon Window را تداعی میکند. دیوار پوششی واقع در طبقهی دوم، بدون بازشو در نظر گرفته شده است که علاوه بر تقویت رابطهی بیرون و درون به لحاظ بصری تا بیشترین حد ممکن، بهعنوان حدفاصل کنترلکنندهی تبادل حرارت و برودت بین دو فضای زیستمحیطی کنترلشدهی داخلی و عرصهی کنترلنشدهی خارجی نیز عمل میکند. نعل درگاه یکپارچه و عریان فلزیِ استفادهشده برای درِ پارکینگ، که فصل مشترک پنجرهی یکپارچه در لایهی دوم و پایهی سنگی در لایهی اول است، شوخطبعی تکتونیک قابل تاملی دارد. در پیشآمدگی کنسول طبقهی دوم نیز عریانبودن سازهی بنا قابل مشاهده است. خطوط عریان سازه در سازماندهی تناسبات و کمپوزیسیون نما نقشی اساسی ایفا میکنند، با این حال، تقدم و تاخر ساختار سازه و سازماندهی نما دارای ابهام هیجانانگیزی است: آیا این خطوط سازهای هستند که به طراحی نما چهارچوب دادهاند یا اینکه برعکس، این چهارچوب کمپوزیسیون نما است که به تقسیمات سازهای نظام میبخشد؟

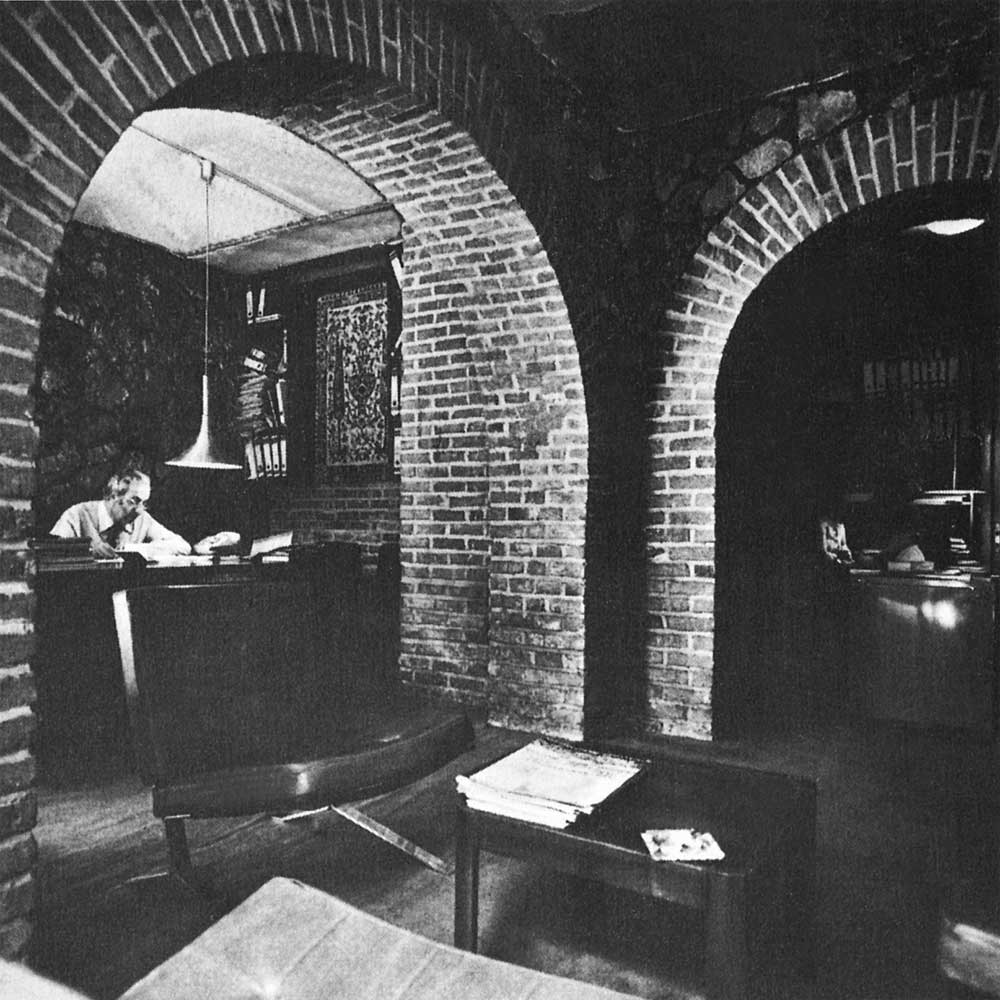

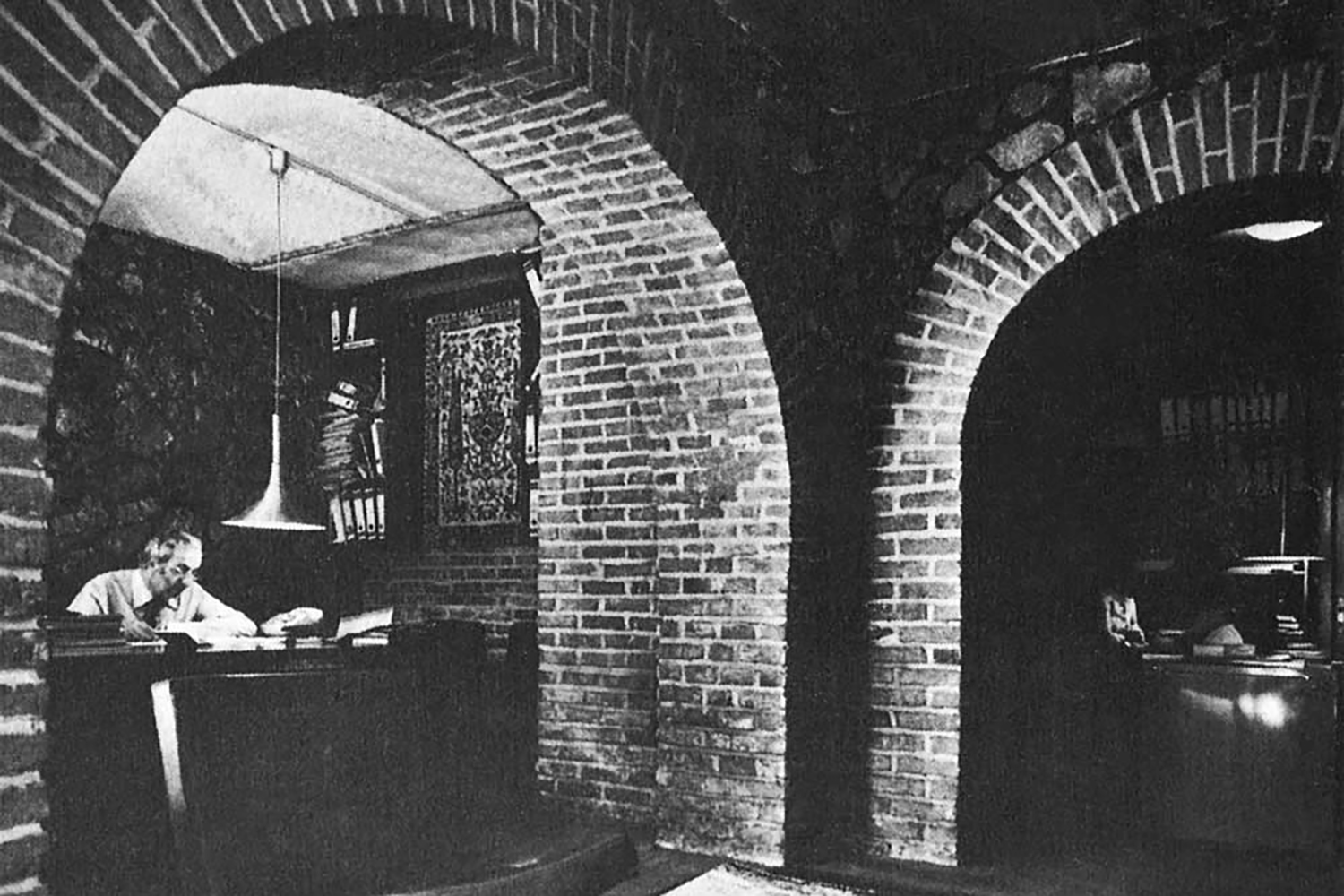

تناسبات تورفتگی چهارچوب درِ ورودی، پیشفضای عمیقی را برای ساختمان ایجاد کرده است. در حرکت از این آستانهی عمیق از فضای شهری بیرون به حوزهی خصوصی درون بنا، مخاطب با تضاد زبان مدرن طراحی جدارهی خارجی و طاقبندی آجری سنتی فضاهای داخلی مواجه میشود. در عین حال، تکنیک کلاژ دیتیلهای دقیق و نادقیق و مصالح پرداختشده و بدون پرداخت و نیز شبکهی منظم و دقیق آجری در طاقبندیها در کنار دیوارچینی سنگهای غیرمنظم –که در عین حال خطهای جداکنندهی نسبتا دقیقی دارند- در تصاویر مختلف داخلی پروژه دیده میشوند. سازهی عریانِ بنا در جایجای پرسپکتیوهای داخلی، انتظامبخش و سامانده چینش مواد و مصالح و تقسیمات فضایی در عرض و طول و ارتفاع فضاهای داخلی است.

تضاد زبان مدرن طراحی جدارهی خارجی و طاقبندی آجری سنتی داخلی، شباهت بسیاری با دوگانگی طراحی معماری آپارتمان مولیتر (Immeuble Molitor Appartmant)، اثر لو کربوزیه دارد که سال 1934 در نزدیکی پارک پرنس (Parc Des Princes) در شهر پاریس ساخته شده بود. منزل مسکونی لو کربوزیه که وی در تمام طول عمر در آن زندگی کرده بود نیز در طبقات فوقانی همان بنا واقع است. ساختمان، نمایی از شیشه و پوسته داشته و ساختار پوستهی خارجی آن دارای دیتیلهای ساختمانی بسیار دقیق میباشد. در تضاد با دقت جزئیات پوستهی خارجی، در فضاهای داخلی آپارتمان خود لو کربوزیه، زبانی متفاوت و متشکل از سقفهای طاقی و دیوارهای آجری قدیمی مشاهده میشود. سؤال این است که آیا این شباهت در کلاژ زبانهای متضاد معماری در طراحی داخلی و خارجی یک آپارتمان، میان پروژهی سیحون و آپارتمان لو کربوزیه اتفاقی است یا نشانگر بخشی از روح زمانه و یا معلول شباهت در جهانبینی و روش و منش طراحی این دو معمار؟

سیحون در آتلیه ی شخصی خود

Seyhoun’s Private Residence and Studio

The greatest challenge in designing a house lies in achieving an optimal balance between the architect’s aesthetic aspirations and the inhabitants’ personal needs, desires, and ideals regarding the intimate realm of their everyday life. While the overall organization of interior and exterior spaces is shaped by the architect’s conceptual framework and overarching design ideas, ultimately, the building’s occupants must experience the genuine feeling of being at home beneath the roof conceived by the architect. From this perspective, houses—and indeed, any buildings—that architects design for themselves are of particular interest. If we accept that, ideally, the design of a house should emerge from an architecturally informed analysis of its inhabitants’ character, then a house that an architect builds for himself is, in effect, his own biography materialized in structure, materials, and spatial organization. Such buildings, more than any other type, reveal the personal origins and inner world of their creators. In the residence and office of Hooshang Seyhoun, located on Jomhouri Street and built on a 10 × 23 meter plot with a total floor area of approximately 440 square meters, one encounters a distinctive combination of stone and steel. Seyhoun was unafraid of the direct exposure of materials; yet this boldness did not lead him into the impersonal abstraction of the International Style, in which architectural language often reduces to visual economy. The building’s façade is a highly successful collage of modern construction techniques and the material culture that defines them. Rising from the ground on a base of unpolished, squared stone blocks, the structure establishes a composition of weight and solidity. The contrast between the precise framing of the windows and the irregular cuts of the stone pieces creates a compelling visual dialogue. In the next layer, an exemplary curtain wall appears—clearly evoking one of the Five Points of Modern Architecture: the ribbon window. The second-floor curtain wall, designed without openings, reinforces the visual connection between inside and outside to the greatest possible extent while acting as a mediating membrane—regulating thermal exchange between the controlled interior environment and the uncontrolled exterior domain. The exposed steel lintel above the garage door—linking the continuous window of the upper level with the stone base below—reveals a remarkable tectonic playfulness. The projecting cantilever of the second floor further exposes the building’s structural logic. The naked structural lines play a central role in organizing the proportions and composition of the façade. Yet, there remains a deliberate ambiguity: do these lines represent the structural framework that determines the façade’s design, or is it the compositional logic of the façade that imposes order upon the structure?

This tension between structure and surface is one of the design’s most stimulating aspects. The recessed proportions of the entrance frame create a deep transitional space for the building. As one moves through this threshold—from the public urban realm into the private domestic interior—one encounters the striking contrast between the modern language of the exterior façade and the traditional brick vaulting of the interior. At the same time, Seyhoun’s collage technique—combining precise and rough details, polished and raw materials, and the juxtaposition of orderly brick networks with roughly assembled yet rhythmically jointed stonework—is consistently visible throughout the interior spaces. The exposed structural system serves as an ordering framework within the spatial composition, regulating the alignment and proportion of materials and spaces in width, length, and height. This contrast between the modern exterior and the traditional vaulted interior closely recalls the duality of design found in Le Corbusier’s Immeuble Molitor Apartment (1934), near Parc des Princes in Paris. Le Corbusier’s personal residence—where he lived for the rest of his life—occupied the upper levels of that same building. Its façade, composed of glass and smooth surfaces, displayed an exacting modernist precision in construction details, while the apartment’s interior revealed an entirely different vocabulary: arched ceilings and aged brick walls. The question arises: is the parallel use of contrasting architectural languages in the interiors and exteriors of both Seyhoun’s house and Le Corbusier’s apartment a mere coincidence, or does it reflect a deeper spirit of the age—a shared worldview and design ethos linking these two architects across cultures and contexts?

سیحون در آتلیه ی شخصی خود

نمای داخلی استودیوی کار لو کربوزیه در واحد مسکونی او که طاقبندی واقع در استودیو و دیوار آجری قدیمی مجاور آن را نشان میدهد.

نمای منزل و آتلیه ی شخصی سیحون، تهران، 1333

وضعیت موجود، بهمن 1393. مقایسهی آتلیه هوشنگ سیحون و آپارتمان مولیتر، لو کربوزیه.

آپارتمان مولیتر، لو کربوزیه، پاریس، 1934 (1313 خورشیدی)