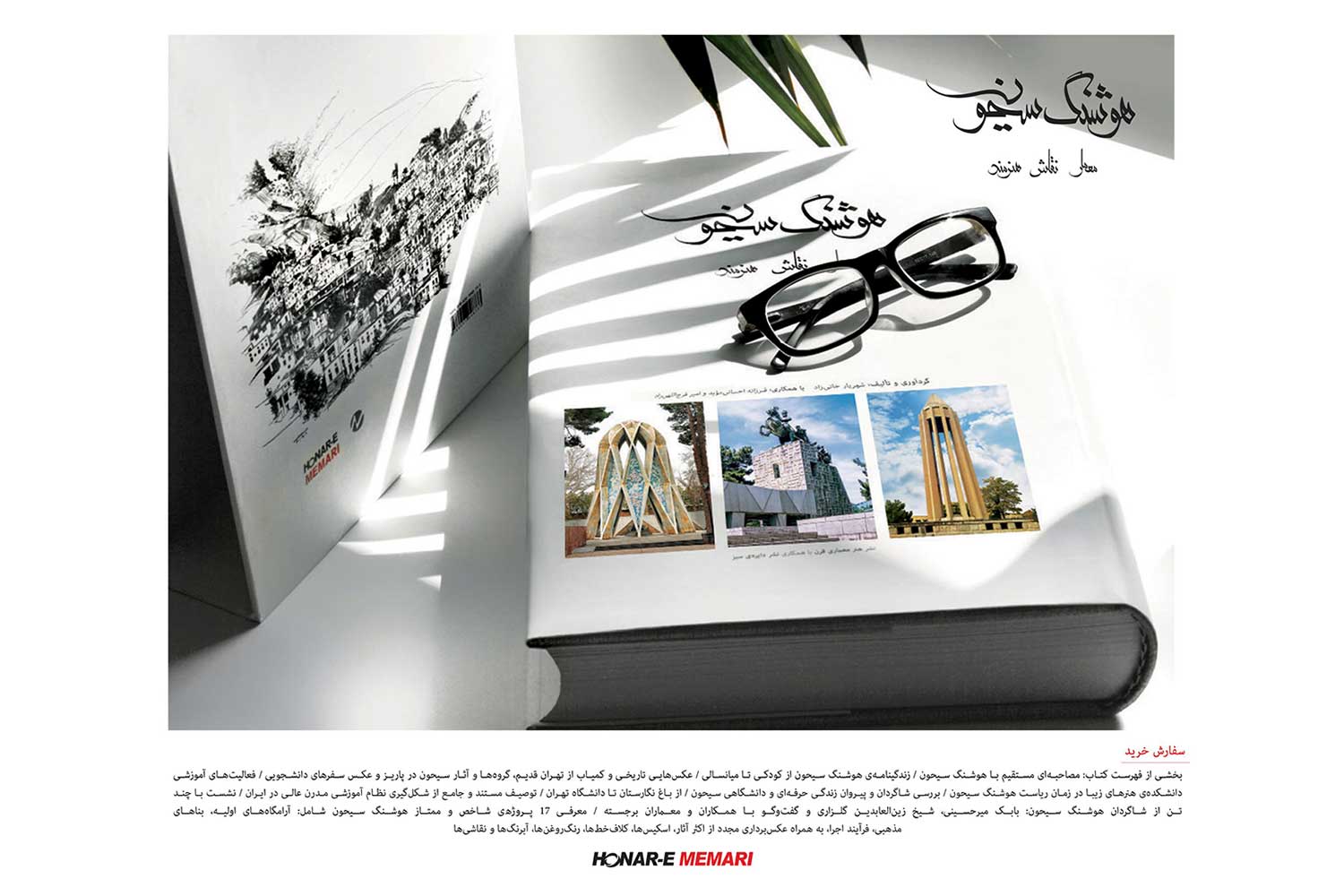

خانهی دولتآبادی اثر هوشنگ سیحون

نیاوران، تهران، 1348

Dowlatabadi House, designed by Hooshang Seyhoun

Niavaran, Tehran, 1969

خانهی دولتآبادی اثر هوشنگ سیحون

خانهی دولتآبادی یکی از تاثیرگذارترین تلاشهای معماران ایرانی در میدان تلفیق سنتها و مفاهیم معماری تاریخی با معماری مدرن محسوب میشود که تاثیر آن را در آثار معمارانی نظیر دیبا، اردلان، فرمانفرماییان و امانت شاهد هستیم. بهراستی میتوان موزهی هنرهای معاصر دیبا را –از لحاظ کانسپت ارجاع به گذشته- فرزند خلف این بنا دانست، ضمن آنکه ساختمان میراث فرهنگی هم نمونهی تکاملیافتهی این نگرش در کاربرد فرمهای تاریخی و بهکارگیری ترکیبی از مصالح مدرن و سنتی همچون بتن و آجر میباشد. حتا استفاده از گنبد ترکین در بنای میراث فرهنگی هم چندان در معماری ایرانی رایج نبوده و قطعا متاثر از تجربهی سیحون در خانهی دولتآبادی میباشد. اما گذشته از جنبهی اثرگذاری معماری این خانه بر معماران قدَر اواخر دورهی پهلوی دوم، علت اهمیت و نقاط مثبت آن را باید در تلاش سیحون در سه حوزهی اساسی در رویارویی با مفهوم تلفیق دانست:

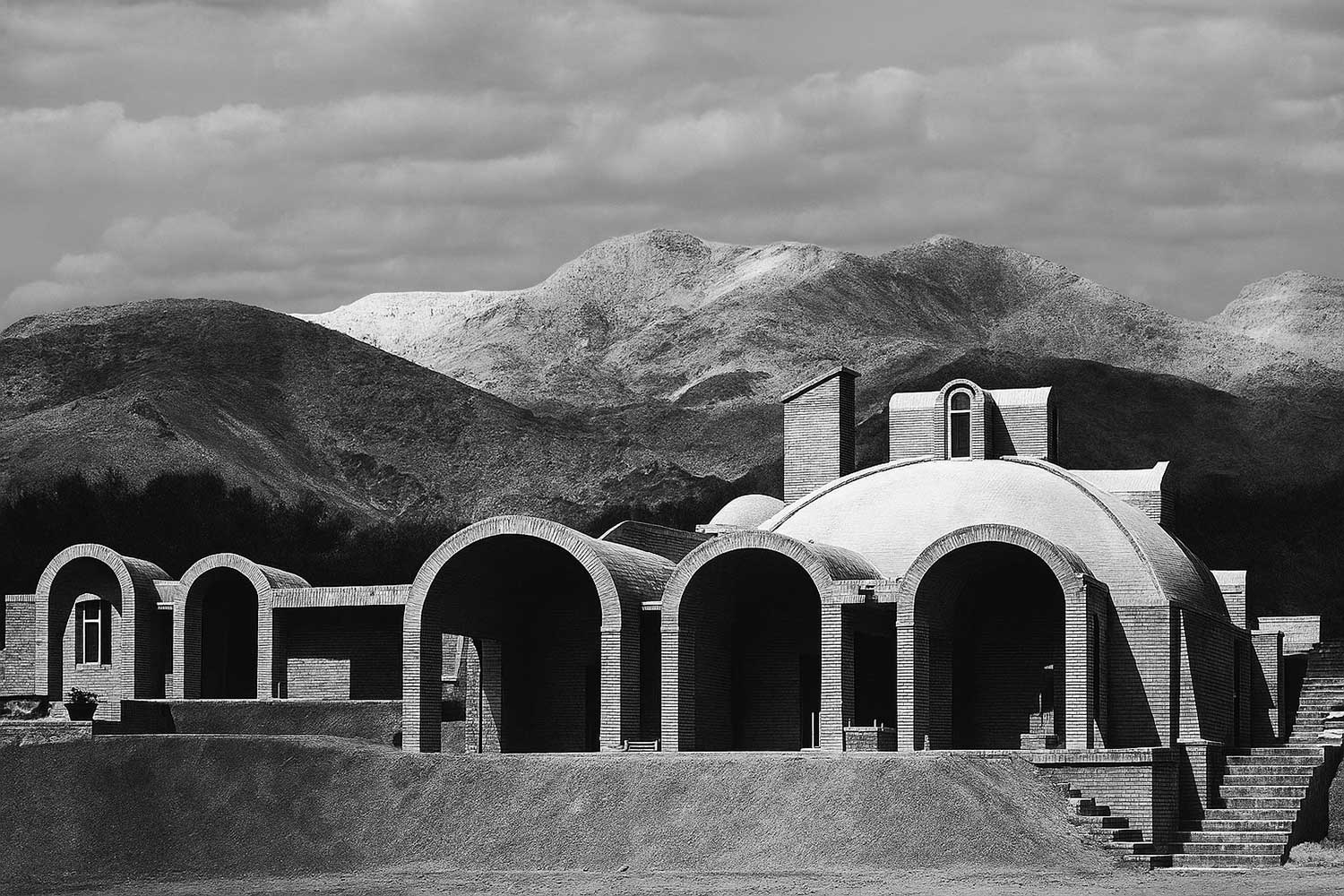

1. حوزهی فرم: قطعا اوج تکامل معماری ایرانی تا پیش از دورهی قاجار در شهرهای مهم حاشیهی کویر، چون یزد، اصفهان و کاشان به چشم میخورد و سازهی طاقی نقش بسیار اساسی در ساختار ابنیه و سازمان فضایی ساختمانها ایفا میکند (شهرهای تبریز، تهران، رشت و اراک اساسا در دوران قاجار بهعنوان شهرهایی تکوینیافته محسوب میشوند). بنابراین فرمهای منحنی در ترکیب با خطوط مستقیم عمودی و افقی، شخصیت فرمال بناهای سنتی را شکل میدهند. سیحون نیز در این پروژه سعی کرده تا ترکیبی اینچنینی را در فرم بناها ایجاد کند. سیحون با استفاده از قوسهای قطاع دایره یا نیمدایره و پرهیز از اجرای قوسهای تیزهدار بر جدایی خود از سنت بهعنوان یک تکرارکنندهی صرف، تأکید کرده است. احجام عمودی مرتفعتر از طاقها نیز یادآور ترکیب بادگیرهایی با احجام منحنی در شهرهایی مانند یزد و نائین میباشند. بنابراین سیحون در حوزهی فرم به بهترین شکل، تجربهی سالیان دراز حضور در بطن بناهای تاریخی و طراحی از آنها را به کار بسته است.

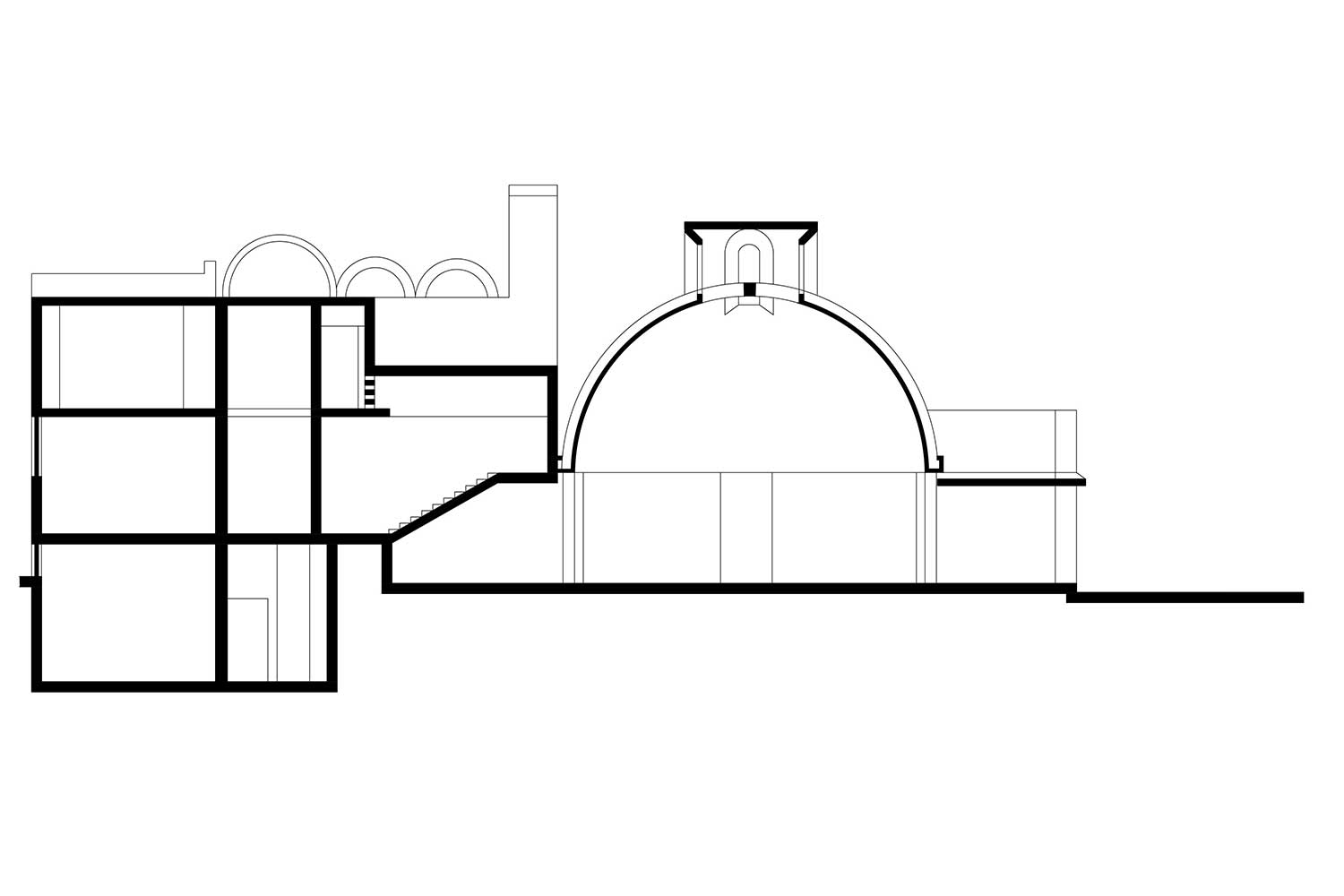

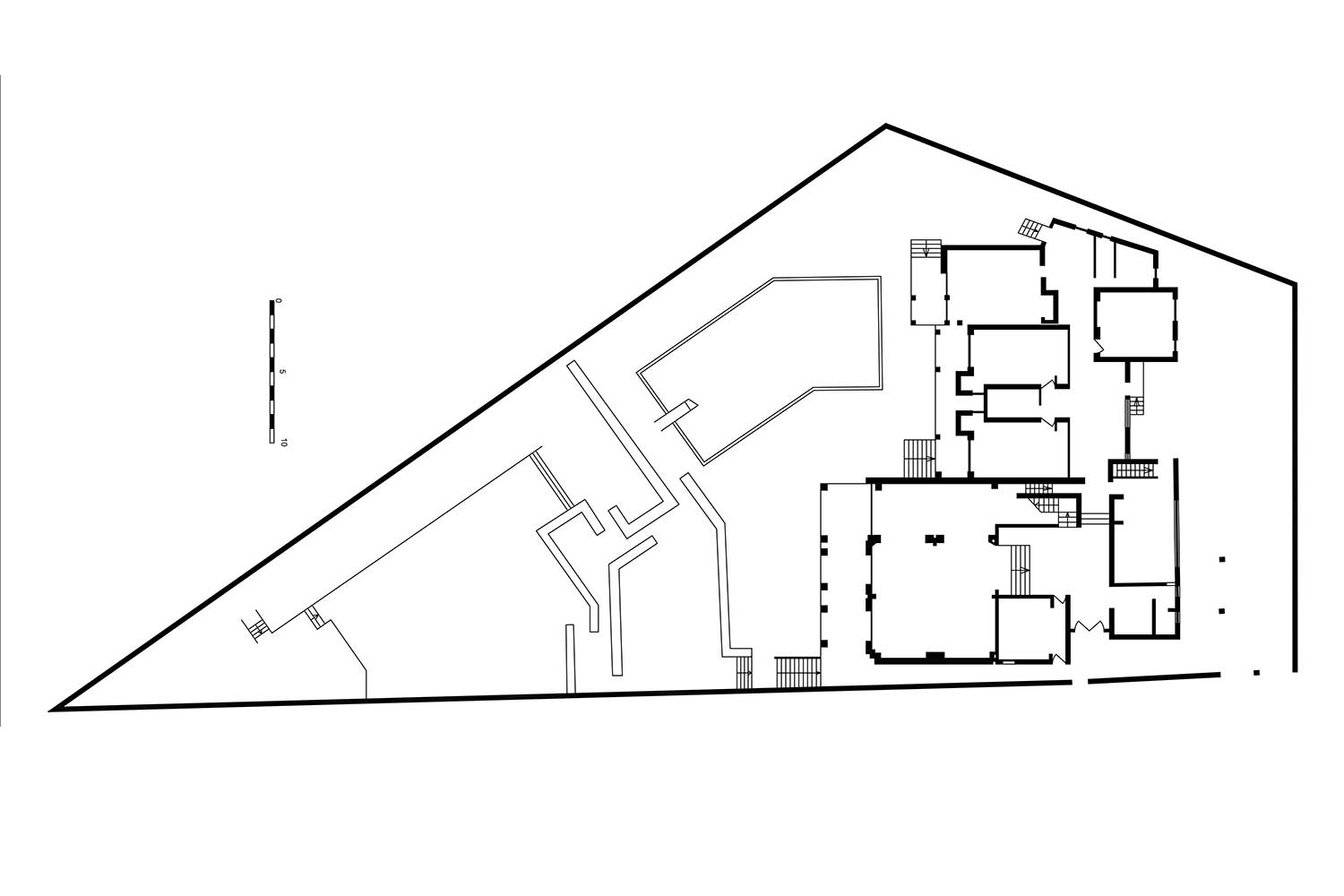

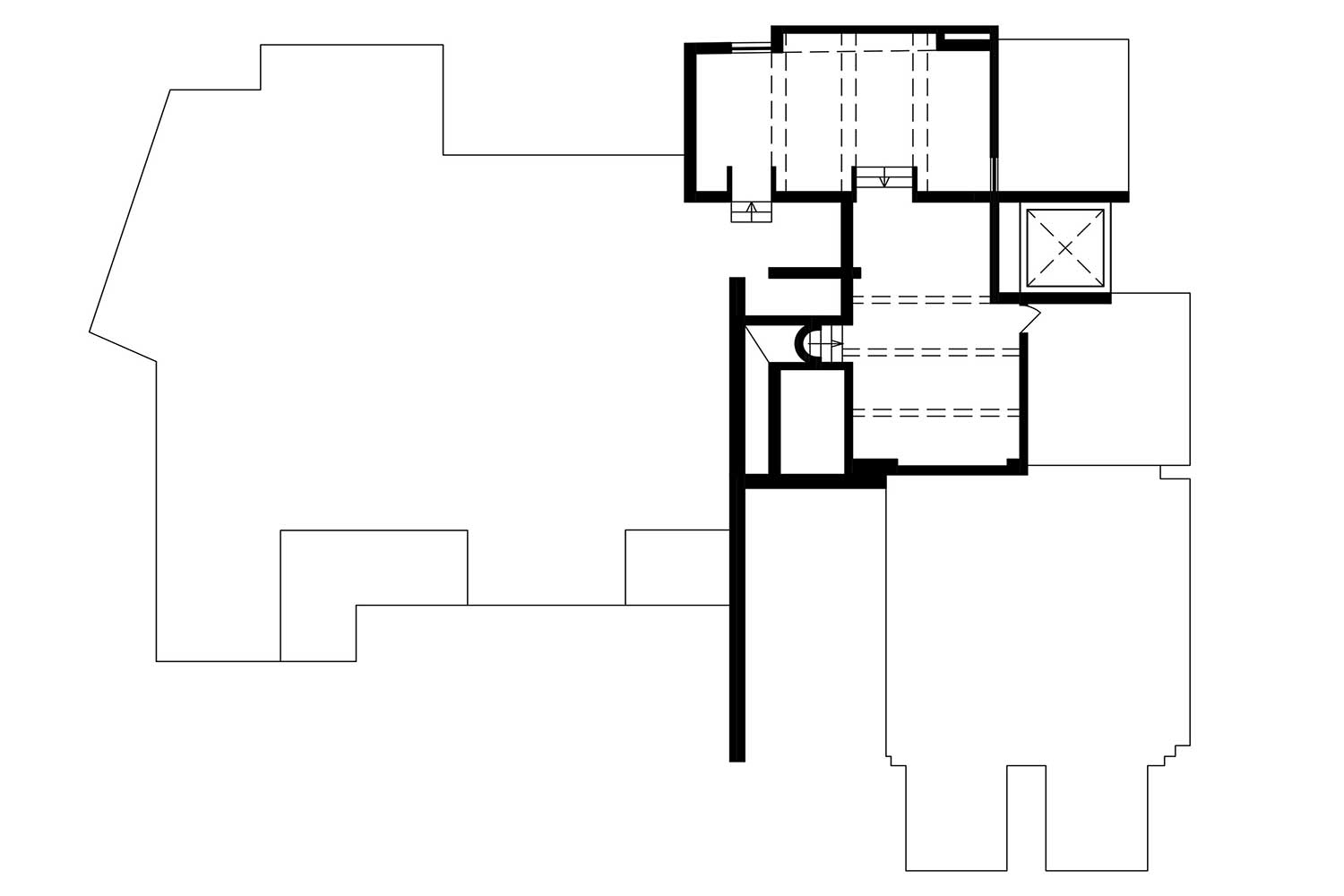

2. حوزهی سازمان فضایی: سیحون اگرچه حوزهی سازمان فضایی را بهعنوان پایهی طراحی خود در نظر نگرفته و در واقع یک پلان عملکردی مدرن را شکل داده اما سعی کرده تا با استفاده از هندسهی متقارن، در محدودههایی از بنا اشاراتی به سازمان فضایی معماری تاریخی ایران داشته است. همچنین گنبد ترکین در سالن اصلی، پلانی مربع که محبوب معماری گذشتهی ایرانی بوده را شکل داده است، ضمن آنکه رواق هم، بهعنوان یکی از عناصر مرسوم در سازمان فضایی معماری ایرانی، در ساختار این بنا مورد توجه قرار گرفته است.

3. حوزهی مصالح: اگرچه مصالح ایرانی در آجر خلاصه نمیشود ولی معماری ایرانی و آجر قرین یکدیگرند و شاید به همین دلیل سیحون آجر را بهعنوان شاخصترین عنصر شکلدهندهی بیان معماری ایرانی مورد توجه قرار داده است. یقینا او در این معماری، استفاده از آجر را به تعالی رسانده و با شناختی که داشته، بهدرستی از ریتمهای آجر در حرهچینیها، اجرای قوسها و حتا اجرای مشبکهای آجری استفاده کرده است؛ در حالی که استفاده از آجر به صورت کلهراسته در معماری ایرانی رایج نبوده و متأثر از معماری آجری انگلیسی است.

سیحون در اینجا هم اقدام به تلفیق سنت و مدرنیته کرده، پس بتن، بهعنوان نمایندهی معماری مدرن، باید جایگاهی در مصالح این بنا داشته باشد. بهویژه باید توجه داشت که معمار بزرگی به نام لویی کان که قطعا مورد توجه سیحون بوده، نمونههای باارزشی در ساخت فرمهای تاریخی با بتن ارائه داده است.

در مجموع میتوان اذعان داشت که بنای خانهی دولتآبادی نه تنها در هر سه حوزهی توضیح دادهشده موفقیتهای چشمگیری به دست آورده و در هیچیک راه اغراق را در پیش نگرفته و به یک معماری هماهنگ دست پیدا کرده بلکه این بنا نقطهی عطفی در آثار سیحون محسوب میشود.

Dowlatabadi House, designed by Hooshang Seyhoun

The Dowlatabadi House is considered one of the most influential endeavors by Iranian architects in merging traditional and historical architectural concepts with modern architecture. Its influence can clearly be seen in the works of architects such as Kamran Diba, Nader Ardalan, Abdolaziz Farmanfarmaian, and Hossein Amanat. In fact, Diba’s Museum of Contemporary Art may rightly be regarded—conceptually, in its reference to the past—as a true successor to this building, while the Cultural Heritage Organization building represents a more developed manifestation of the same approach in employing historical forms and combining modern and traditional materials such as concrete and brick. Even the use of a ribbed dome in the Cultural Heritage building—an element uncommon in Iranian architecture—is undoubtedly inspired by Seyhoun’s experiment in the Dowlatabadi House. Yet beyond its direct influence on prominent architects of the late Pahlavi era, the true significance and strength of this building lies in Seyhoun’s threefold endeavor to engage with the concept of synthesis, expressed through form, spatial organization, and materiality.

1. Form

The pinnacle of Iranian architectural evolution prior to the Qajar era is most vividly evident in the desert-edge cities such as Yazd, Isfahan, and Kashan, where vaulted structures played an essential role in the architectural and spatial composition of buildings. (Cities like Tabriz, Tehran, Rasht, and Arak are generally regarded as fully developed only in the Qajar period.) Hence, in traditional Iranian architecture, curvilinear forms—in combination with horizontal and vertical lines—define the visual character of the structures. Seyhoun, in this project, sought to create a similar fusion of elements. By employing circular or semi-circular arches and avoiding pointed ones, he emphasized his departure from tradition as a mere act of repetition. The taller vertical masses rising beside the vaults evoke the combination of windcatchers and domed forms typical of cities such as Yazd and Na’in. In this way, Seyhoun masterfully transformed his long years of study and documentation of historical architecture into a fresh formal language.

2. Spatial Organization

Although Seyhoun did not base his design on traditional Iranian spatial organization—instead developing a modern functional plan—he still introduced references to the symmetrical geometry and spatial hierarchy of Iranian architecture within certain parts of the building. The ribbed dome above the main hall rests upon a square plan, a configuration much beloved in Iranian tradition. Likewise, the inclusion of a ravaq (portico)—one of the essential elements of Iranian architectural planning—demonstrates Seyhoun’s awareness of historical spatial logic even within a modern framework.

3. Materiality

While Iranian architecture cannot be reduced solely to brick, brickwork has always been closely intertwined with its identity. For this reason, Seyhoun chose brick as the defining material for expressing the Iranian architectural spirit. In the Dowlatabadi House, he elevated brick construction to a level of artistry—using it with deep understanding in the rhythmic arrangement of bricks across the vaults, in the construction of arches, and even in brick lattice screens. His adoption of stretcher–header bonding (kalleh-raasteh), uncommon in Iranian practice, reflects the influence of English brick architecture. At the same time, Seyhoun’s consistent pursuit of synthesis led him to include concrete—the emblematic material of modern architecture—within the palette of the building. This gesture recalls the architectural philosophy of Louis Kahn, whose reinterpretation of historical forms in concrete undoubtedly influenced Seyhoun’s approach.

In summary, the Dowlatabadi House stands as a rare example of balance and coherence, having achieved significant success in all three areas—form, spatial organization, and materiality—without resorting to excess or superficiality. It represents not only one of Seyhoun’s most mature and complete works, but also a milestone in the evolution of modern Iranian architecture.

مدارک فنی