افتتاح موزهی بزرگ مصر؛ نمایش کامل آرامگاه توتعنخآمون برای نخستین بار

موزهی بزرگ مصر، جیزه، مصر / دفتر معماری هنِگان پِنگ

Egypt’s Grand Museum opens, displaying Tutankhamun tomb in full for first time

The Grand Egyptian Museum , Giza, Egypt / Heneghan Peng Architects

افتتاح موزهی بزرگ مصر؛ نمایش کامل آرامگاه توتعنخآمون برای نخستین بار

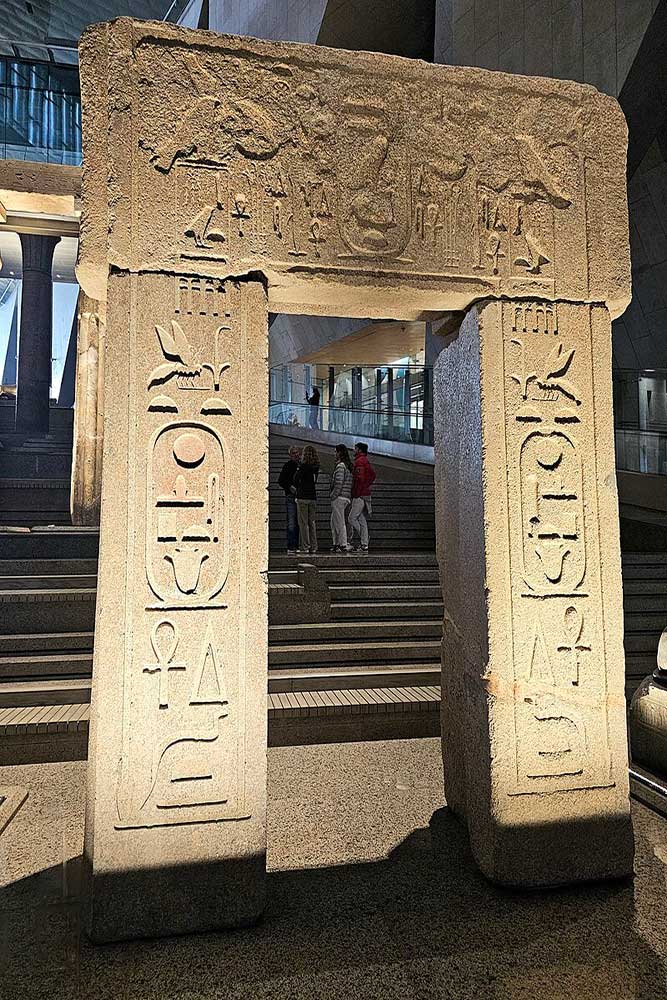

در نزدیکی یکی از عجایب هفتگانهی دنیای باستان – هرم بزرگ خوفو در جیزه – مصر رسما موزهای را افتتاح کرده است که آن را نقطهی اوج فرهنگی عصر مدرن خود میداند. موزهی بزرگ مصر (Grand Egyptian Museum – GEM)، که از آن بهعنوان بزرگترین موزهی باستانشناسی جهان یاد میشود، حدود صد هزار شی تاریخی را در خود جای داده که بیش از هفت هزار سال از تاریخ این سرزمین را، از دوران پیشدودمانی تا دورههای یونانی و رومی، در بر میگیرد. باستانشناسان برجستهی مصری بر این باورند که تاسیس این موزه قدرت استدلال آنان را برای بازگرداندن آثار مهم مصری نگهداریشده در دیگر کشورها تقویت میکند – از جمله سنگ مشهور «روستایتا» (Rosetta Stone) که در موزهی بریتانیا به نمایش گذاشته شده است. مهمترین بخش موزهی بزرگ، نمایش کامل مجموعهی بینظیر آرامگاه «توتعنخآمون» است که برای نخستین بار از زمان کشف آن توسط باستانشناس بریتانیایی، «هاوارد کارتر»، بهصورت کامل در کنار هم به نمایش درآمده است؛ شامل ماسک طلایی مشهور، تخت، ارابهها و دیگر اشیای سلطنتی پادشاه نوجوان. دکتر «طارق توفیق»، رئیس انجمن بینالمللی مصرشناسان و مدیر پیشین موزهی بزرگ، میگوید: «باید میاندیشیدم که چگونه میتوانیم او را به شکلی متفاوت نشان دهیم. از زمان کشف آرامگاه در سال ۱۹۲۲، تنها حدود ۱۸۰۰ شی از مجموع بیش از ۵۵۰۰ قطعه به نمایش درآمده بود. ایدهام این بود که کل آرامگاه را بازسازی کنیم؛ یعنی هیچ چیزی در انبار یا موزههای دیگر باقی نماند تا بازدیدکننده تجربهای کامل، درست همانند هاوارد کارتر، بیش از صد سال پیش داشته باشد.»

این مجموعهی عظیم که ساخت آن حدود ۱٫۲ میلیارد دلار هزینه داشته، انتظار میرود سالانه تا هشت میلیون بازدیدکننده جذب کند و رونقی دوباره به گردشگری مصر بخشد که سالها تحت تاثیر بحرانهای منطقهای آسیب دیده بود. «امید داریم موزهی بزرگ مصر، سرآغاز عصر زرین تازهای برای مصرشناسی و گردشگری فرهنگی باشد»، «احمد صدیق»، راهنمای تور و پژوهشگر مصرشناسی در فلات جیزه میگوید. افزون بر نمایش مجموعهی توتعنخآمون و قایق تدفینی ۴۵۰۰ سالهی خوفو – یکی از کهنترین و سالمترین کشتیهای شناختهشدهی دوران باستان – بیشتر تالارهای موزه از سال گذشته برای عموم باز شده بودند. احمد ادامه میدهد: «در ماههای گذشته تورهای بسیاری به موزه آوردهام، حتی وقتی هنوز بهطور کامل افتتاح نشده بود. اکنون به اوج شکوه خود رسیده است. با گشایش مجموعهی توتعنخآمون، بیگمان جهان بار دیگر به اینجا بازخواهد گشت، چراکه او نماد فرعونها و شناختهشدهترین پادشاه دوران باستان است.»

یک گردشگر اسپانیایی به نام «رائول» که منتظر افتتاح کامل موزه در ۴ نوامبر است، میگوید: «این جایی است که باید دید.»

و «سم» از لندن، که در حال سفر به مصر است، میگوید: «بیصبرانه منتظریم تا همهی آثار را ببینیم؛ فرصتی است که در تمام عمر تنها یکبار پیش میآید.»

گردشگر بریتانیایی دیگری یادآور میشود که پیشتر مجموعهی توتعنخآمون را در موزهی قدیمی مصر در میدان تحریر قاهره دیده است: «آن موزه واقعا شلوغ و گیجکننده بود. امیدوارم موزهی جدید تجربهای منظمتر و قابلدرکتر ارائه دهد.»

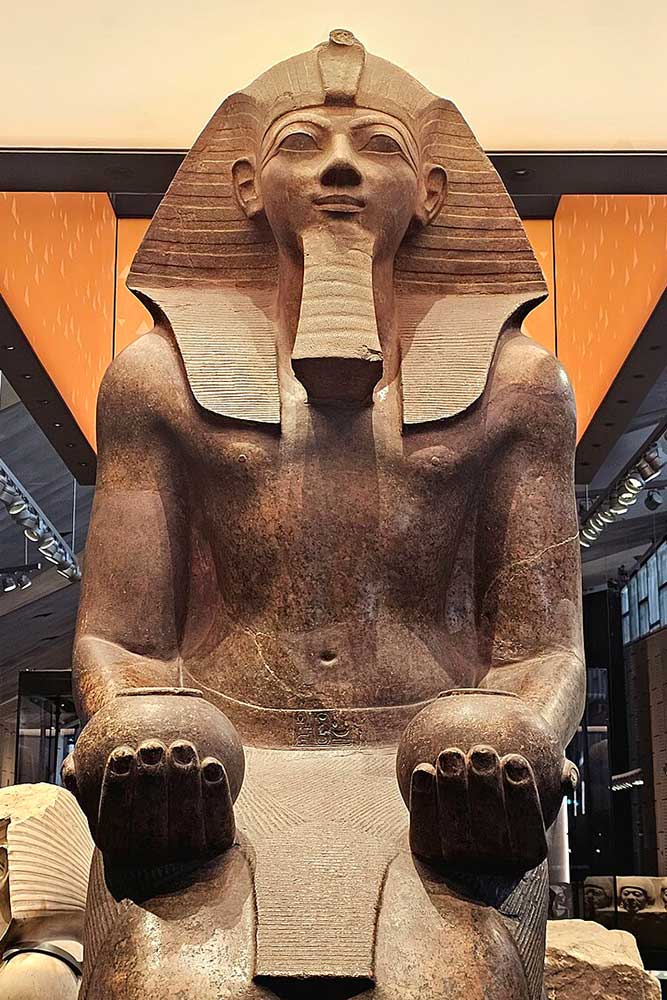

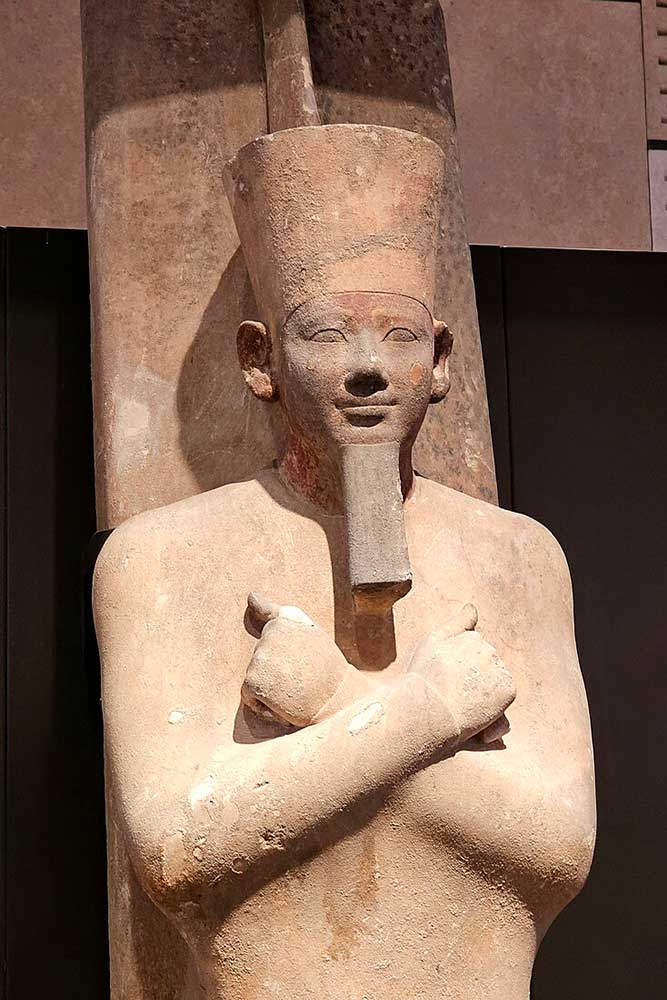

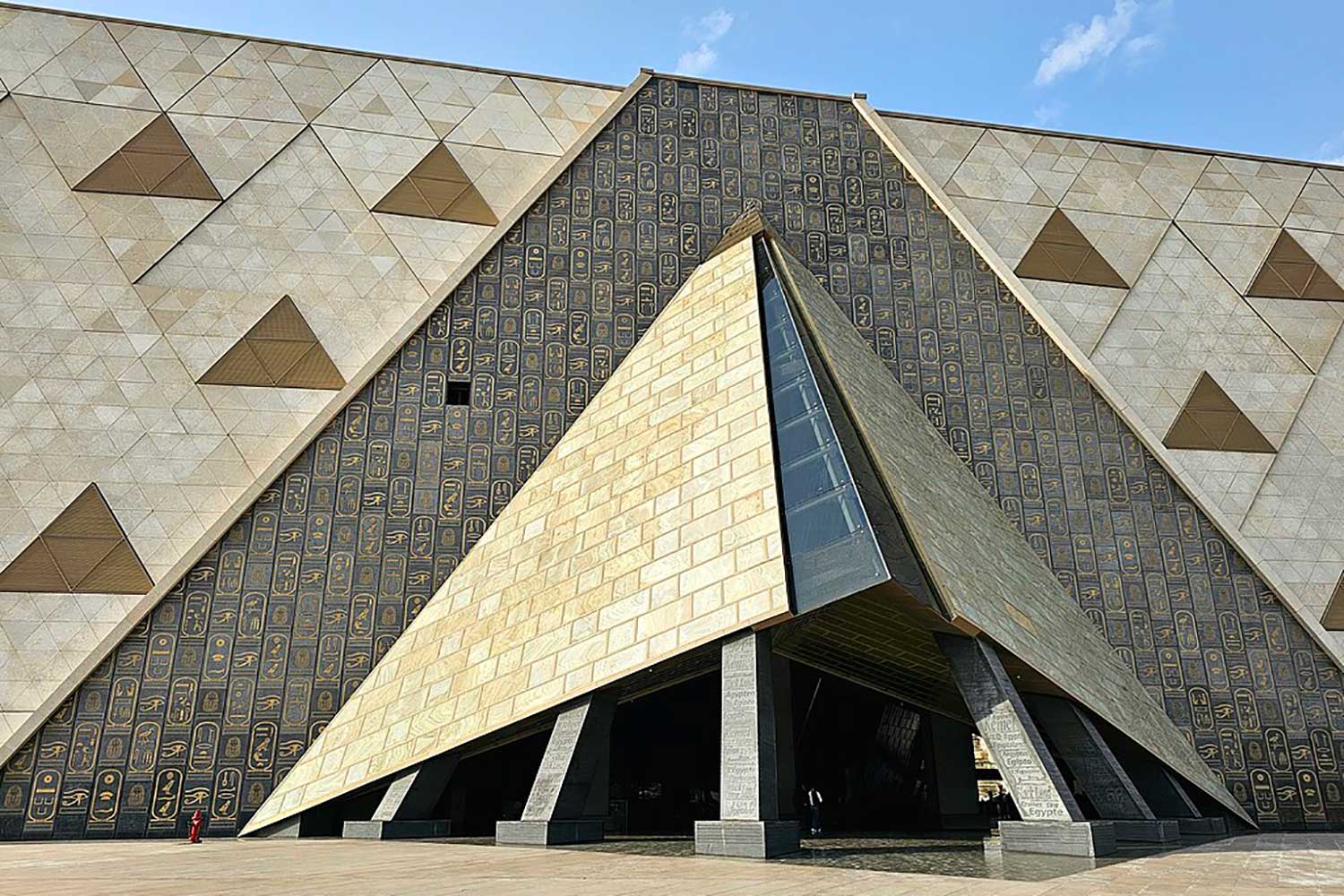

موزهی جدید بنایی عظیم است با وسعت ۵۰۰ هزار متر مربع (حدود ۵٫۴ میلیون فوت مربع)، معادل ۷۰ زمین فوتبال. نمای بیرونی آن از حروف هیروگلیف و سنگ مرمر آلاباستر نیمهشفاف ساخته شده که بهشکل مثلثها تراش خورده و ورودی آن چون هرم طراحی شده است. از چشمگیرترین آثار موزه میتوان به اوبلیسک معلق ۳۲۰۰ سالهی رامسس دوم به طول ۱۶ متر و مجسمهی ۱۱ متری او اشاره کرد. این مجسمهی عظیم در سال ۲۰۰۶ طی عملیات پیچیدهای از نزدیکی ایستگاه راهآهن قاهره به این محل منتقل شد. پلکانی بزرگ با تندیسهای فراعنه و ملکههای باستان آراسته شده و در طبقهی بالا، پنجرهای عظیم منظرهای کامل و قابشده از اهرام جیزه ارائه میدهد. ایدهی ساخت این موزه نخست در سال ۱۹۹۲، در دوران ریاست «حسنی مبارک»، مطرح شد و ساخت آن در سال ۲۰۰۵ آغاز گشت؛ پروژهای که بنا به برآوردها، تکمیلش تقریبا به اندازهی ساخت هرم بزرگ زمان برده است. فرایند ساخت با بحرانهای مالی، انقلاب ۲۰۱۱ موسوم به بهار عربی – که منجر به برکناری مبارک و سالها ناآرامی شد – همهگیری کرونا و جنگهای منطقهای مواجه شد. دکتر زاهی حواس، وزیر پیشین گردشگری و میراث فرهنگی مصر و باستانشناس برجسته، در گفتوگو با بیبیسی میگوید: «این رویای من بود. از دیدن گشایش این موزه بسیار خوشحالم!» او تأکید میکند که این موزه نشان میدهد مصریان در زمینهی کاوش، مرمت و موزهداری همپایهی باستانشناسان غربی هستند.

او ادامه میدهد: «دو چیز میخواهم: نخست اینکه موزهها خرید آثار قاچاق را متوقف کنند، و دوم اینکه سه شی به مصر بازگردد: سنگ روزِتا از موزهی بریتانیا، زودیاک دندرا از لوور، و نیمتنهی نفرتیتی از برلین.»

حواس برای بازگرداندن این آثار دادخواستهای آنلاین به راه انداخته که تاکنون صدها هزار امضا جمع کرده است. سنگ روزِتا که در سال ۱۷۹۹ کشف شد، کلید رمزگشایی خط هیروگلیف بود. آن را ارتش فرانسه یافت و سپس انگلیسیها بهعنوان غنیمت جنگی مصادره کردند. زودیاک دندرا، نقشهی آسمانی مصر باستان، در سال ۱۸۲۱ توسط گروهی فرانسوی از معبد «هاتور» جدا شد. مصریها همچنین آلمانیها را متهم میکنند که بیش از یک قرن پیش، نیمتنهی رنگین نفرتیتی، همسر فرعون آخناتن را بهصورت غیرقانونی از کشور خارج کردهاند. دکتر حواس میگوید: «میخواهیم این سه اثر بهعنوان نشانهی حسن نیت بازگردانده شوند، هدیهای از سه کشور بزرگ، همانگونه که مصر در طول تاریخ هدایای بسیاری به جهان بخشیده است.»

دکتر «مونیکا حنا»، مصرشناس برجستهی دیگر نیز تاکید میکند که همان سه اثر باید بازگردانده شوند، چراکه «تحت پوشش استعماری» به یغما رفتهاند. او میگوید: «موزهی بزرگ مصر پیام روشنی میدهد: مصر کار خود را بهدرستی انجام داده تا بهطور رسمی خواستار بازگشت آثار شود.»

موزهی بریتانیا در پاسخ به بیبیسی اعلام کرده که تاکنون «هیچ درخواست رسمی از سوی دولت مصر برای بازگرداندن یا امانت دادن سنگ روزِتا دریافت نکرده است.»

مصرشناسان مصری ابراز امیدواری کردهاند که این موزه به مرکزی برای پژوهشهای علمی و کشفیات تازه تبدیل شود. محافظان و مرمتگران مصری در این موزه تاکنون بسیاری از اشیای توتعنخآمون را – از جمله زره شگفتانگیز او از جنس چرم و بافت – با دقت بازسازی کردهاند. مطابق قانون مصر، چنین مرمتهایی تنها باید بهدست کارشناسان مصری انجام شود. دکتر توفیق در پایان میگوید: «همکاران ما از سراسر جهان از کیفیت مرمتهای انجامشده شگفتزدهاند. این پروژه مایهی غرور ملی برای همهی ماست. ما در کنار تاریخ باستان مصر، مصرِ معاصر را نیز به نمایش میگذاریم، زیرا همین ملت بود که این موزه را ساخت.»

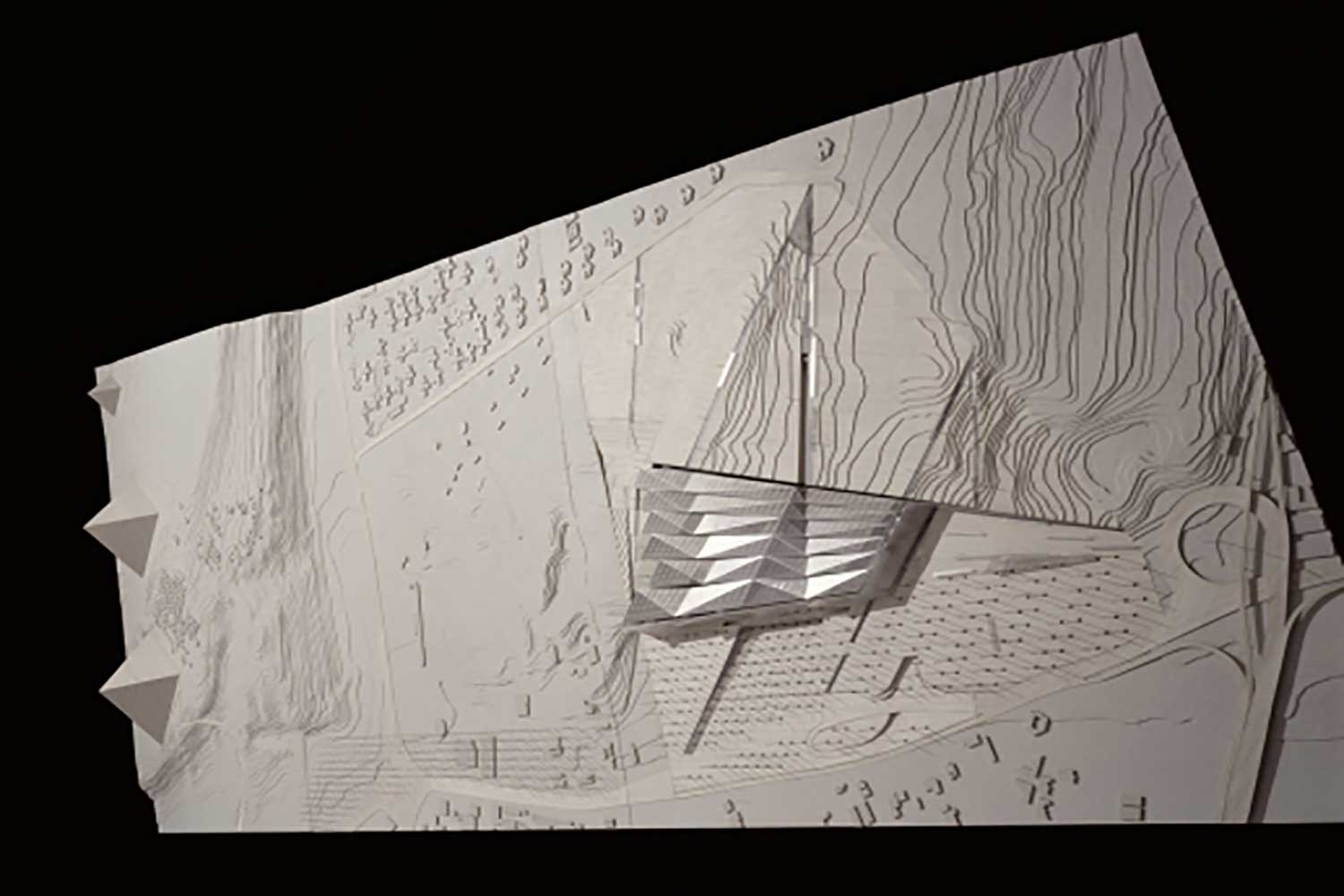

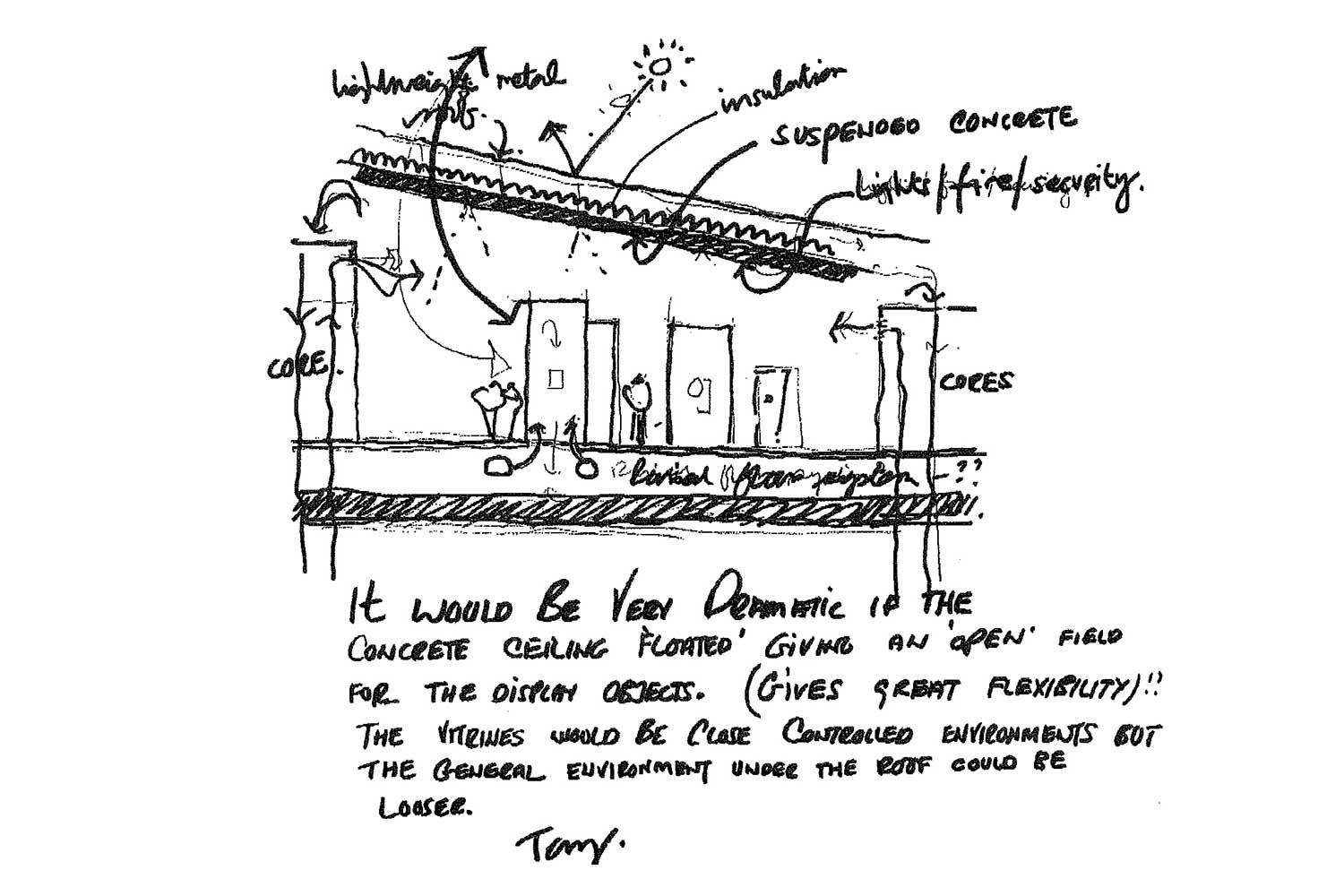

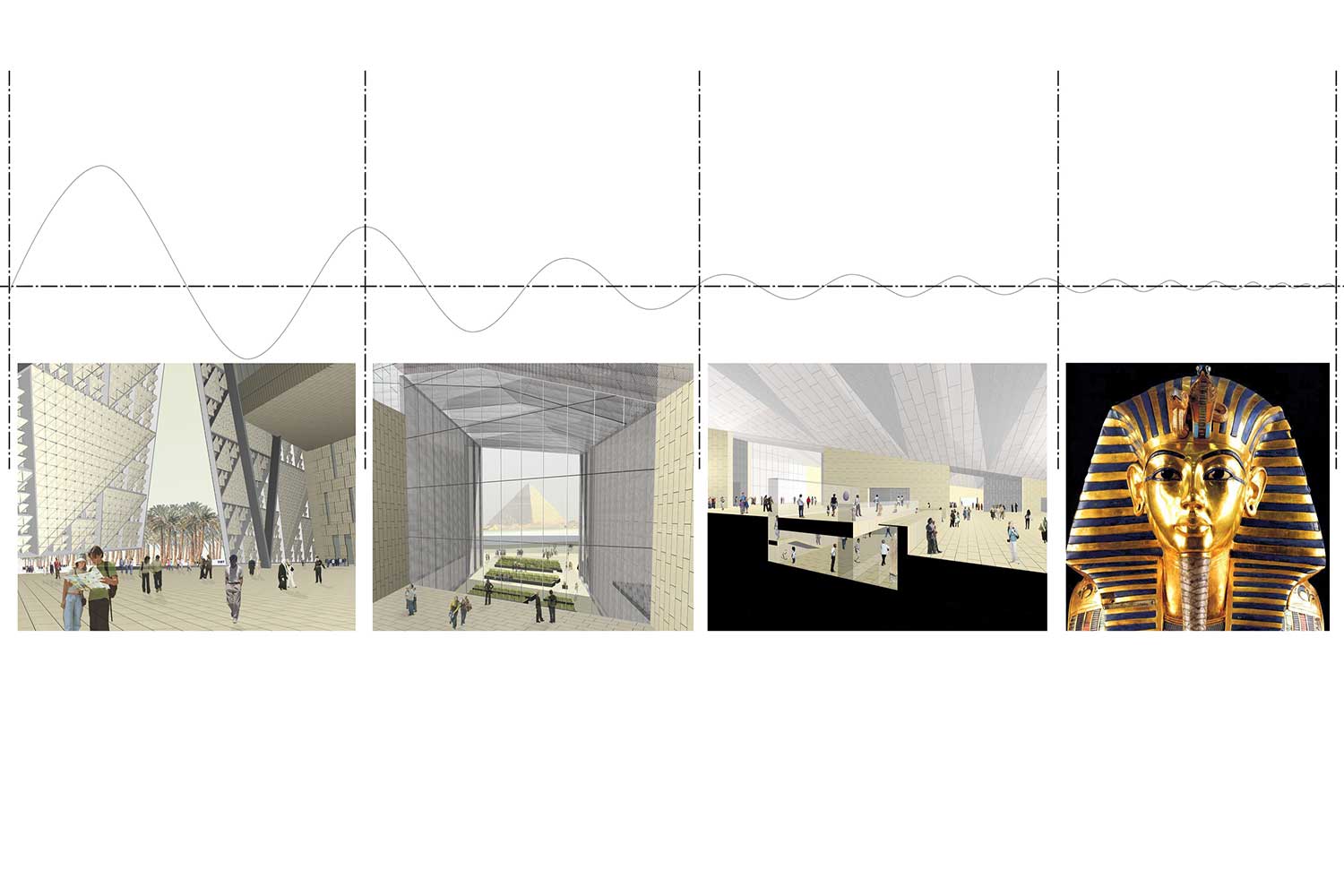

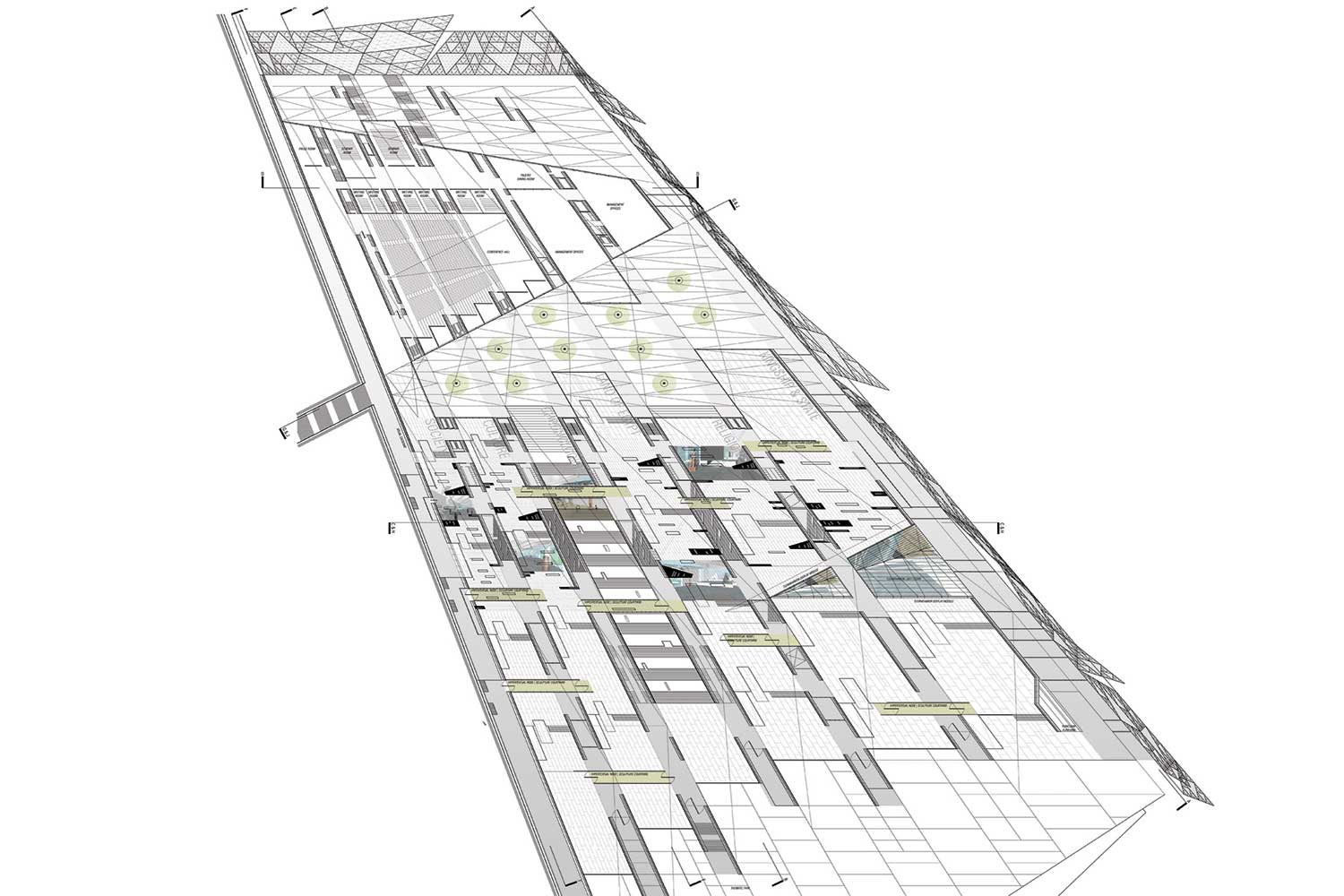

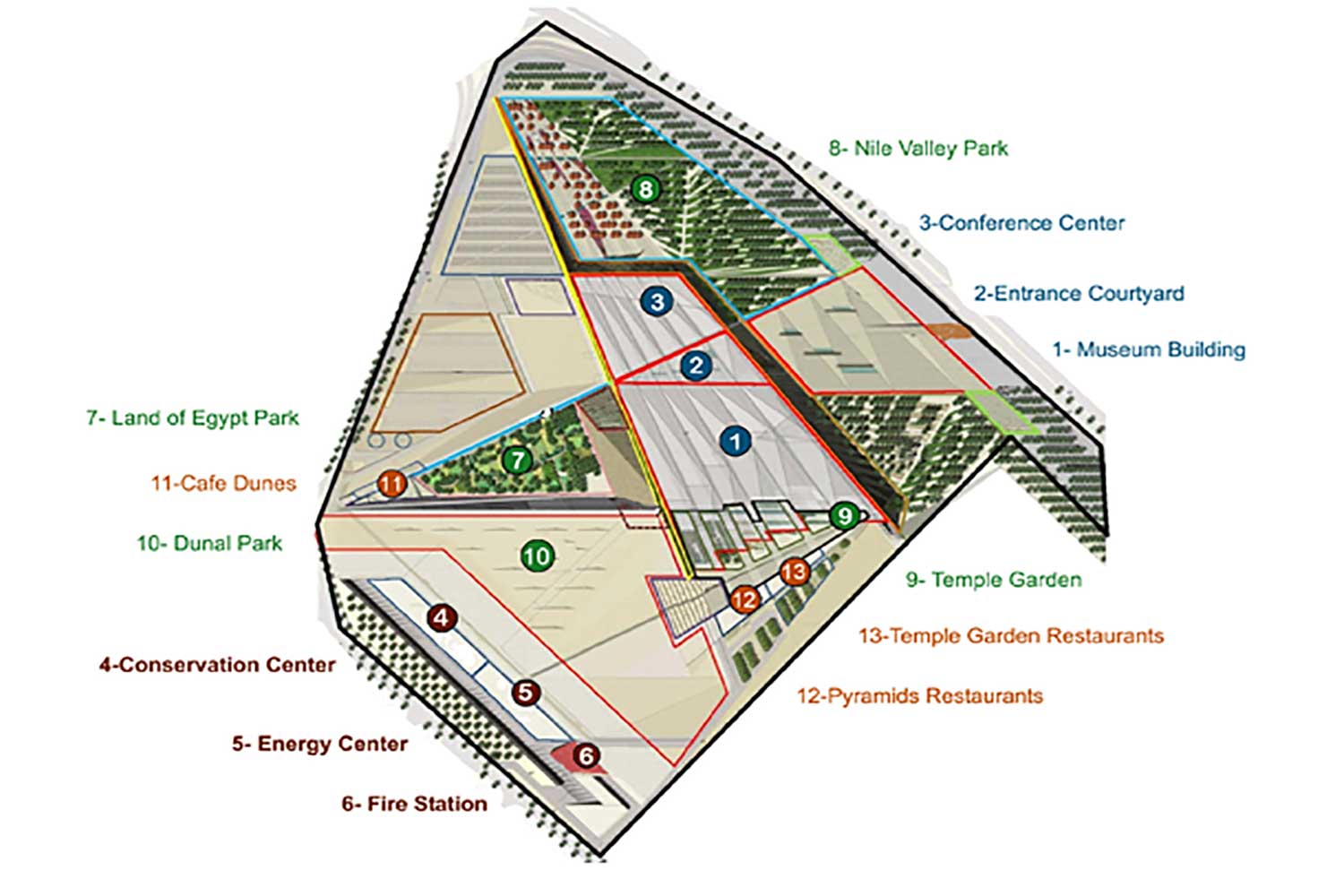

سایت موزهی بزرگ مصر در مرز میان دشت حاصلخیز نیل و پهنهی خشک فلات صحرا قرار دارد؛ جایی در میان اهرام و شهر قاهره. این مکان با اختلاف تراز پنجاهمتری تعریف میشود؛ شکافی طبیعی که در طی هزاران سال، هنگامی که رود نیل مسیر خود را از دل صحرا به سوی دریای مدیترانه تراشیده، چهرهی زمین مصر را شکل داده است. پلکان باشکوه مرکزی (The Grand Staircase) از صحن ورودی آغاز میشود و تا تالارهای نمایش دائمی در طبقهی بالا امتداد مییابد. در مسیر خود از کنار بخشهای نمایش موقت، نمایشهای ویژه و انبار اصلی باستانشناسی میگذرد. این پلکان، مسیری زمانی و روایی در دل موزه است که در نهایت به چشماندازی از اهرام در بالاترین نقطه ختم میشود. پلکان بزرگ بهعنوان نقطهی مرجع بصری، ساختاری قابلشناسایی در موزه پدید میآورد و بازدیدکننده را در پیمایش این بنای عظیم یاری میدهد. طرح موزه بهگونهای است که بازدیدکننده گامبهگام از جهان امروز به جهان فرعونها گذر میکند. میدان باشکوه مقابل موزه نخستین جایی است که مقیاس و شکوه بنا را آشکار میسازد. این میدان بهتدریج شیب میگیرد و به ورودی موزه میرسد؛ به حیاطی سایهدار که گذر از فضای باز بیرونی به درون موزه و مرکز همایشها را نرم و تدریجی میسازد. ساختار سهبعدی موزه با مجموعهای از محورهای دید بصری میان سایت و سه هرم اصلی تعریف شده است؛ چارچوبی که از مقیاس کلان تا جزئیترین عناصر طراحی را دربر میگیرد. طراحی موزه از اختلاف ارتفاع میان درهی نیل و فلات بیابانی بهره میبرد تا «لبهای تازه» در حاشیهی فلات پدید آورد. موزه در میانهی این دو سطح جای میگیرد — نه در ارتفاعی بالاتر از فلات، بلکه چون پلی میان دو بُعد طبیعی سرزمین. حرکت به سوی موزه، سفری است لایهلایه: بازدیدکننده از میدان ورودی عظیم میگذرد، از فضای سایهدار درگاه عبور میکند و بر پلکان بزرگ بالا میرود تا به سطح فلات برسد — همانجا که تالارهای نمایش قرار دارند و برای نخستینبار، چشمانداز اهرام از درون موزه پدیدار میشود. سازمان فضایی موزه بر پایهی پنج محور بصری به سوی اهرام شکل گرفته است؛ محور ششم همان مسیر زمانی پلکان بزرگ است. بازدیدکننده با بالا رفتن از این مسیر، وارد تالارهای دائمی میشود که از آنجا اهرام در افق نمایاناند. تالارها در یک تراز گسترده سازمان یافتهاند تا بازدیدکننده بتواند مقیاس و شکوه تمدن مصر باستان را بهطور یکپارچه درک کند. پنج نوار فضایی موزه با چینخوردگیهای سقف و دیوارهای ضخیم خدماتی تعریف میشوند و در عین نظم، امکان انعطاف در نحوهی نمایش آثار را فراهم میکنند. نور طبیعی از خلال شکستهای سقف کنترل و تعدیل میشود. موزهی بزرگ مصر بهمثابهی یک مجموعهی فرهنگی جامع برای مطالعات مصرشناسی طراحی شده است. این مجموعه شامل ۲۴٬۰۰۰ متر مربع فضای نمایش دائمی (معادل تقریبا چهار زمین فوتبال)، موزهی کودک، تالارهای کنفرانس و آموزش، مرکز بزرگ مرمت آثار باستانی، و باغهایی گسترده در زمینی به وسعت ۵۰ هکتار است. از برجستهترین مجموعههای آن میتوان به آثار توتعنخآمون (Tutankhamun) اشاره کرد که در حال حاضر در موزهی مصر در قاهره نگهداری میشود، و نیز قایق خورشیدی (Solar Boat) که امروزه در کنار اهرام جای دارد.

موزهی بزرگ و مورد انتظار مصر توسط دفتر معماری Heneghan Peng تکمیل شد. این موزه که در فاصلهی اندکی بیش از یک مایل از اهرام جیزه واقع شده، بهزودی بیش از پنجهزار اثر تاریخی را در خود جای خواهد داد و عنوان بزرگترین موزهی جهان را که به یک تمدن واحد اختصاص یافته، از آنِ خود میکند. تالار توتعنخآمون قرار است در نخستین روز نوامبر ۲۰۲۵ به روی عموم گشوده شود. پروژه از یک مسابقهی بینالمللی معماری در سال ۲۰۰۳ آغاز شد؛ مسابقهای که دفتر دوبلینی Heneghan Peng در آن برنده شد و پس از آن در همکاری با شرکتهای Arup و Buro Happold طرح نهایی را توسعه داد. طراحی این موزه بهعنوان پلی میان تاریخ کهن و نوآوری معاصر تصور شد. «طراحی موزهای با چنین جایگاه و اهمیت، در مجاورت بنایی به عظمت و نمادینگی اهرام، فرصتی است که تنها یکبار در زندگی پیش میآید»، «رویشین هنِگان»، یکی از بنیانگذاران دفتر، میگوید. «هدف ما در این طرح، تقویت پیوند میان تاریخ و مکان است؛ خلق خانهای برای آثاری که پیشتر هرگز دیده نشدهاند و اکنون بر زمینی آرمیدهاند که زمانی آنها را زاده است.»

بافت جغرافیایی محل، نقشی اساسی در شکلگیری طرح داشته است. موزه بر فراز فلاتی صحرایی جای گرفته که در گذر زمان بهدست رود نیل شکل گرفته و ساختمان بهسوی اهرام گشوده میشود؛ محور دید آن دقیقاً در امتداد سه هرم اصلی قرار دارد. خطوط شعاعی دیوارها و سقف، فرمی بادبزنی پدید میآورند که از هندسهی اهرام الهام گرفته اما هرگز در ارتفاع با آنها رقابت نمیکند. در قلب موزه، پلکانی ششطبقه جای دارد که دو سوی آن با آثار یادمانی عظیمی چون ده مجسمه از «سنوسرت یکم» آراسته شده است. این مسیر، بازدیدکننده را بهگونهای زمانی از دوران پیشدودمانی تا عصر قبطی هدایت میکند. سفر در طبقهی بالا، در تالار دائمی توتعنخآمون به اوج میرسد و در نهایت با چشماندازی فراگیر از اهرام پایان مییابد. نور طبیعی تا حد امکان در طراحی بهکار رفته است، هرچند مانند همهی موزهها، ملاحظات حفاظتی ایجاب میکند که این نور بیشتر در فضاهایی مورد استفاده قرار گیرد که آثار مقاومتری را در خود جای دادهاند. سازهی بتنی تقویتشدهی بنا به تنظیم دمای درونی کمک میکند و نیاز به تهویهی مکانیکی را کاهش میدهد. فراتر از نقش موزهای خود، موزهی بزرگ مصر بهعنوان مرکزی فرهنگی و آموزشی برای قاهره نیز طراحی شده است. در همکاری با معماران منظر West 8، باغهای گستردهی آن بازتابی از سرسبزی و حیات درهی نیل هستند. موزه همچنین یکی از بزرگترین مراکز مرمت و پژوهش در جهان را در خود جای داده است؛ مجموعهای شامل ۱۷ آزمایشگاه تخصصی که از طریق تونلی زیرزمینی به ساختمان اصلی متصل میشوند. این بخش، میراث عظیم مصر را – از پاپیروسهای شکننده و منسوجات گرفته تا پیکرهها، سفالینهها و بقایای انسانی – حفاظت و نگهداری میکند. تکمیل موزهی بزرگ مصر نقطهی عطفی در تاریخ میراث این سرزمین است؛ بنایی که همچون سندی از تداوم شکوه مصر و نفوذ همیشگی آن در تمدن جهانی بر جای خواهد ماند.

Egypt’s Grand Museum opens, displaying Tutankhamun tomb in full for first time

Near one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World – the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza – Egypt has officially opened what it intends as a cultural highlight of the modern age. The Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), described as the world’s largest archaeological museum, is packed with some 100,000 artefacts covering some seven millennia of the country’s history from pre-dynastic times to the Greek and Roman eras. Prominent Egyptologists argue that its establishment strengthens their demand for key Egyptian antiquities held in other countries to be returned – including the famed Rosetta Stone displayed at the British Museum. A main draw of the GEM will be the entire contents of the intact tomb of the boy king Tutankhamun, displayed together for the first time since it was found by British Egyptologist Howard Carter. They include Tutankhamun’s spectacular gold mask, throne and chariots. “I had to think, how can we show him in a different way, because since the discovery of the tomb in 1922, about 1,800 pieces from a total of over 5,500 that were inside the tomb were on display,” says Dr Tarek Tawfik, president of the International Association of Egyptologists and former head of the GEM. “I had the idea of displaying the complete tomb, which means nothing remains in storage, nothing remains in other museums, and you get to have the complete experience, the way Howard Carter had it over a hundred years ago.” Costing some $1.2bn (£910m; €1.1bn), the vast museum complex is expected to attract up to 8m visitors a year, giving a huge boost to Egyptian tourism which has been hit by regional crises. “We hope the Grand Egyptian Museum will usher in a new golden age of Egyptology and cultural tourism,” says Ahmed Seddik, a guide and aspiring Egyptologist by the pyramids on the Giza Plateau. Apart from the Tutankhamun exhibit and a new display of the spectacular, 4,500-year-old funerary boat of Khufu – one of the oldest and best-preserved vessels from antiquity – most of the galleries at the site have been opened to the public since last year. “I’ve been organising so many tours to the museum even though it was partially open,” Ahmed continues. “Now it will be at the pinnacle of its glory. When the Tutankhamun collection opens, then you can imagine the whole world will come back, because this is an iconic Pharoah, the most famous king of all antiquity.”

“It’s an absolute must-see,” says Spanish tourist, Raúl, who is awaiting the full public opening on 4 November. “We’re just waiting to go and check out all of the Egyptian artefacts,” says Sam from London, who is on an Egypt tour. “It’s a once in a lifetime opportunity.” Another British tourist says she previously saw the Tutankhamun exhibits on display at the neoclassical Egyptian Museum in bustling Tahrir Square. “The old museum was pretty chaotic, and it was a bit confusing,” she comments. “Hopefully the Grand Museum will be a lot easier to take in and I think you will just get more out of it.” The new museum is colossal, spanning 500,000 square metres (5.4m sq ft) – about the size of 70 football pitches. The exterior is covered in hieroglyphs and translucent alabaster cut into triangles with a pyramid shaped entrance. Among the GEM showstoppers are a 3,200-year-old, 16m-long suspended obelisk of the powerful pharaoh, Ramesses II, and his massive 11m-high statue. The imposing statue was moved from close to the Cairo railway station in 2006, in a complex operation in preparation for the new institution. A giant staircase is lined with the statues of other ancient kings and queens and on an upper floor a huge window offers a perfectly framed view of the Giza pyramids. The museum was first proposed in 1992, during the rule of President Hosni Mubarak, and construction began in 2005. It has now taken nearly as long to complete as the Great Pyramid, according to estimates. The project was hit by financial crises, the 2011 Arab Spring – which deposed Mubarak and led to years of turmoil – the Covid-19 pandemic, and regional wars. “It was my dream. I’m really happy to see this museum is finally opened!” Dr Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s former long-time minister of tourism and antiquities, tells the BBC. The veteran archaeologist says it shows that Egyptians are equals of foreign Egyptologists when it comes to excavations, preservation of monuments and curating museums. “Now I want two things: number one, museums to stop buying stolen artefacts and number two, I need three objects to come back: the Rosetta Stone from the British Museum, the Zodiac from the Louvre and the Bust of Nefertiti from Berlin.” Dr Hawass has set up online petitions – attracting hundreds of thousands of signatures – calling for all three items to be repatriated. The Rosetta Stone, found in 1799, provided the key to deciphering hieroglyphics. It was discovered by the French army and was seized by the British as war booty. A French team cut the Dendera Zodiac, an ancient Egyptian celestial map, from the Temple of Hathor in Upper Egypt in 1821. Egypt accuses German archaeologists of smuggling the colourfully painted bust of Nefertiti, wife of Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten, out of the country more than a century ago. “We need the three objects to come as a good feeling from these three countries, as a gift, as Egypt gave the world many gifts,” Dr Hawass says. Another leading Egyptologist, Dr Monica Hanna, names the same objects, “taken under a colonialist pretext”, as ones which must be repatriated. She adds: “The GEM gives this message that Egypt has done its homework very well to officially ask for the objects.” The British Museum told the BBC that it had received “no formal requests for either the return or the loan of the Rosetta Stone from the Egyptian Government”. Egyptian Egyptologists voice their excitement about the new museum becoming a centre for academic research, driving new discoveries. Already, Egyptian conservators based there have painstakingly restored items belonging to Tutankhamun, including his impressive armour made of textiles and leather. According to Egyptian law, such restorations can only be done by Egyptians. “Colleagues from around the world have been in awe of the fantastic conservation work that has been done,” says Dr Tawfik, adding that the entire project is a source of great national pride. “As well as ancient Egyptian history, we are also showcasing modern Egypt because it’s Egypt that built this museum.”

The site for the Grand Egyptian Museum is located at the edge of the first desert plateau between the pyramids and Cairo. It is defined by a 50m level difference, created as the Nile carves its way through the desert to the Mediterranean, a geological condition that has shaped Egypt for over 3,000 years. The Grand Staircase ascends from the Entrance Court to the permanent exhibition galleries on the top floor stopping off at special exhibitions, temporary exhibition, and Archaeological Main Storage. The staircase is the chronological route within the museum, culminating in the view of the pyramids at the top of the stair. An identifiable reference point, the Grand Staircase allows visitors to easily navigate this vast Museum. The museum is designed so that the visitor moved through a sequence of spaces to gradually transition from the contemporary world back into the world of the Pharaohs. The monumental forecourt in front of the museum is the first point from which the visitor can grasp the scale and monumentality of the site. Gradually sloping upwards to the entrance, the visitor is led into the Entrance Court, a shaded outdoor space which continues the transition from outdoor space to museum and conference. A 3-dimensional structure inscribed by a set of visual axes from the site to the three pyramids defines the framework within which the museum emerges, from the overall scale of the site to the smallest of details.The design of the museum utilises the level difference between the Nile Valley and the desert plateau to construct a new ‘edge’ to the plateau. The museum exists between the level of the Nile Valley and the plateau, never extending above the plateau. The approach to the museum is a series of layers, whereby the visitor moves through a monumental forecourt, a shaded entrance area and a grand staircase that ascends to plateau level, the level at which the galleries are located where for the first time the visitor sees the pyramids from within the museum. The museum is structured in five bands by the visual axes to the pyramids, the sixth band being the chronological route of the grand stair. Having ascended through the Museum, the visitor enters the permanent exhibition areas from where the pyramids can be seen. The galleries are organised on one floor to allow the visitor to comprehend the scale and magnificence of the civilisation whilst the five bands are spatially structured by the structural roof folds and heavy service walls. A clear organisation is provided to a large space yet still allowing flexible modes of display. Natural light is modulated and controlled by the roof folds. The museum is envisaged as a cultural complex of activities devoted to Egyptology and will contain 24,000m² of permanent exhibition space, almost 4 football fields in size, a children’s museum, conference and education facilities, a large conservation centre and extensive gardens on the 50hA site. The collections of the museum include the Tutankhamen collection, that is currently housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, and the Solar Boat that is now housed beside the pyramids.

The highly anticipated Grand Egyptian Museum has been completed by Heneghan Peng Architects. Located just over a mile from the Pyramids of Giza, the landmark institution will showcase more than 5,000 artefacts and is set to become the largest museum in the world dedicated to a single civilisation. Its Tutankhamun Gallery will open to the public on November 1 2025. The project originated from an international architecture competition held in 2003, won by the Dublin-based firm, which then collaborated with Arup and Buro Happold. Their design was envisioned as a bridge between ancient history and modern innovation. ‘Designing a museum of this calibre, in such close proximity to a landmark as monumental and symbolic as the pyramids, is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,’ says Heneghan Peng founding partner Róisín Heneghan. ‘Our design works to strengthen that connection to history and place, providing a home for some never-before-seen artefacts that rests upon the very land from which they were created.’ The museum’s geographical context played a key role in shaping its design. Perched on a desert plateau formed by the Nile, the building radiates outward toward the pyramids, its visual axis aligning with the three ancient structures. The radial lines of its walls and roof create a fan shape that echoes the shape of the pyramids, but which doesn’t rival their height. At the heart of the museum lies a six-story staircase lined with monumental artefacts – such as the ten statues of King Senusret I – which leads visitors chronologically through Egypt’s history, from the Predynastic Period through to the Coptic era. The journey culminates at the top floor, home to the Tutankhamun Gallery’s permanent exhibitions, before opening out to a panoramic view of the pyramids. Natural light is used wherever possible, although – as with all museums – this must take conservation concerns into account, and is mainly employed in areas housing more robust artefacts. Reinforced concrete helps regulate internal temperatures, reducing reliance on air conditioning. Beyond its role as a world-class exhibition space, the Grand Egyptian Museum is envisioned as a cultural and educational hub for Cairo. Developed with landscape architects West 8, its extensive gardens evoke the verdant beauty of the Nile Valley. The museum also includes one of the largest conservation and research facilities in the world, featuring 17 specialised laboratories connected to the main building via an underground tunnel. These labs safeguard Egypt’s vast heritage – from fragile papyri and textiles to sculptures, pottery and human remains. The completion of the Grand Egyptian Museum marks a milestone in the country’s heritage, standing as a testament to Egypt’s enduring influence on world civilisation.

برگهی اطلاعات (Fact Sheet)

کارفرما: وزارت فرهنگ مصر (Ministry of Culture, Egypt)

زیربنا: ۱۰۰٬۰۰۰ متر مربع

تاریخ: ۲۰۰۳ (مرحلهی مسابقه)

وضعیت: تکمیلشده

موقعیت: جیزه، مصر

همکاران پروژه

معماران (قاهره): RMC

مهندسی سازه، عمران و ترافیک: Arup | ACE (Cairo)

تاسیسات ساختمان: Buro Happold | Shaker Engineering (Egypt)

مدیریت تیم طراحی: Davis Langdon

برآورد هزینه (QS): Davis Langdon

مهندسی نما: Arup

فناوری اطلاعات، امنیت، آتشنشانی و آکوستیک: Buro Happold

طراحی منظر: West 8 | Sites International (Egypt)

نورپردازی تخصصی: Bartenbach LichtLabor

طراحی گرافیک و نشانهگذاری فضاها: Bruce Mau Design

طراحی کلان نمایشگاهها: Metaphor

موزهشناسی: Cultural Innovations

عکاسی: Iwan Baan

Fact sheet

Client: Ministry of Culture, Egypt

Size: 100,000m²

Date: 2003 (Competition)

Status: Complete

Location: Giza, Egypt

Collaborators

Architects (Cairo): RMC

Structural | Civil | Traffic: Arup | ACE (Cairo)

Building Services: Buro Happold | Shaker Engineering (Egypt)

Design Team Management: Davis Langdon

QS: Davis Langdon

Facade Engineering: Arup

IT | Security | Fire | Acoustics: Buro Happold

Landscape: West 8 | Sites International (Egypt)

Specialist Lighting: Bartenbach LichtLabor

Signage: Bruce Mau Design

Exhibition Masterplanning: Metaphor

Museology: Cultural Innovations

Photography: Iwan Baan

مدارک فنی