آزمایشگاه انرژی آکادمی هاوایی؛ معماریِ سبزِ هوشمند در دامنههای کوه کوهالا، دفتر معماری فلنزبرگ آرکیتکتز

Hawaii Preparatory Academy Energy Lab / Flansburgh Architects

آزمایشگاه انرژیِ «هاوایی پرپ» (Hawaii Prep’s Energy Lab) در میان سه حجم خطی با پوشش تختهچوبی و نوارکوبی محصور شده است؛ هرکدام دارای بامی مجزا هستند که بهصورت پلکانی در امتداد زمینِ تراسدار پایین میآیند.

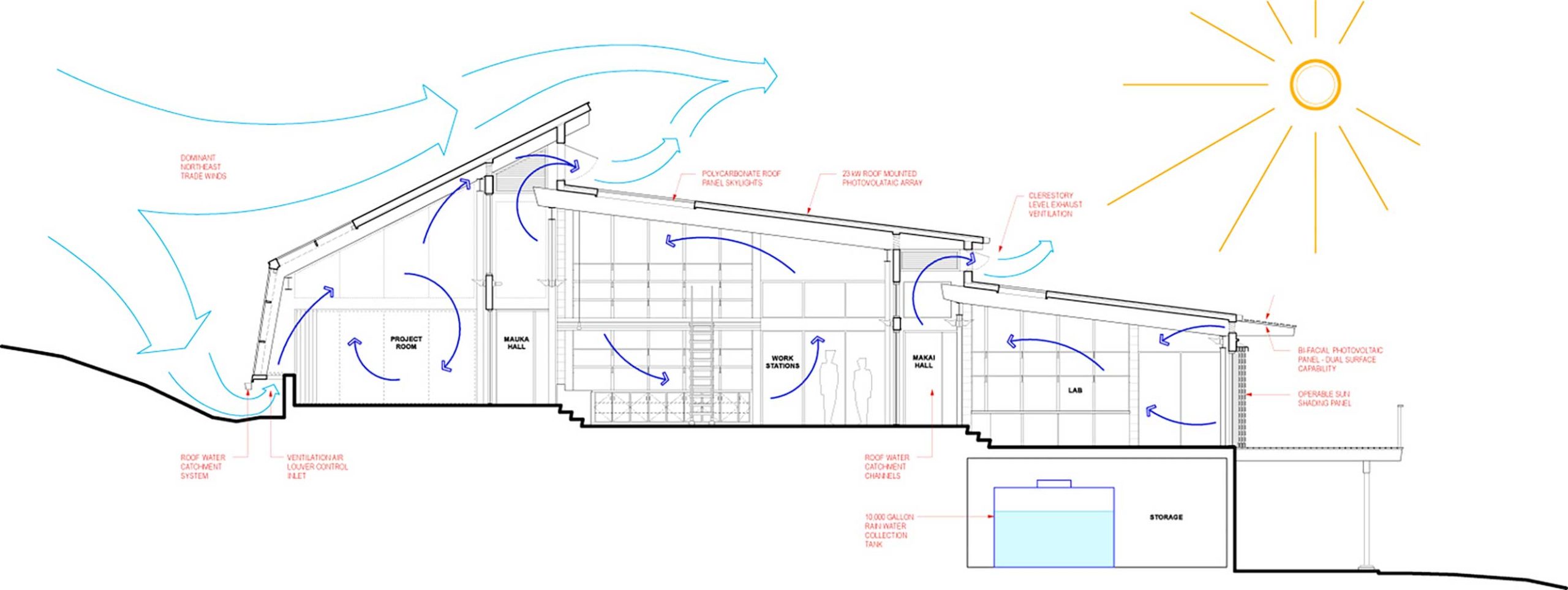

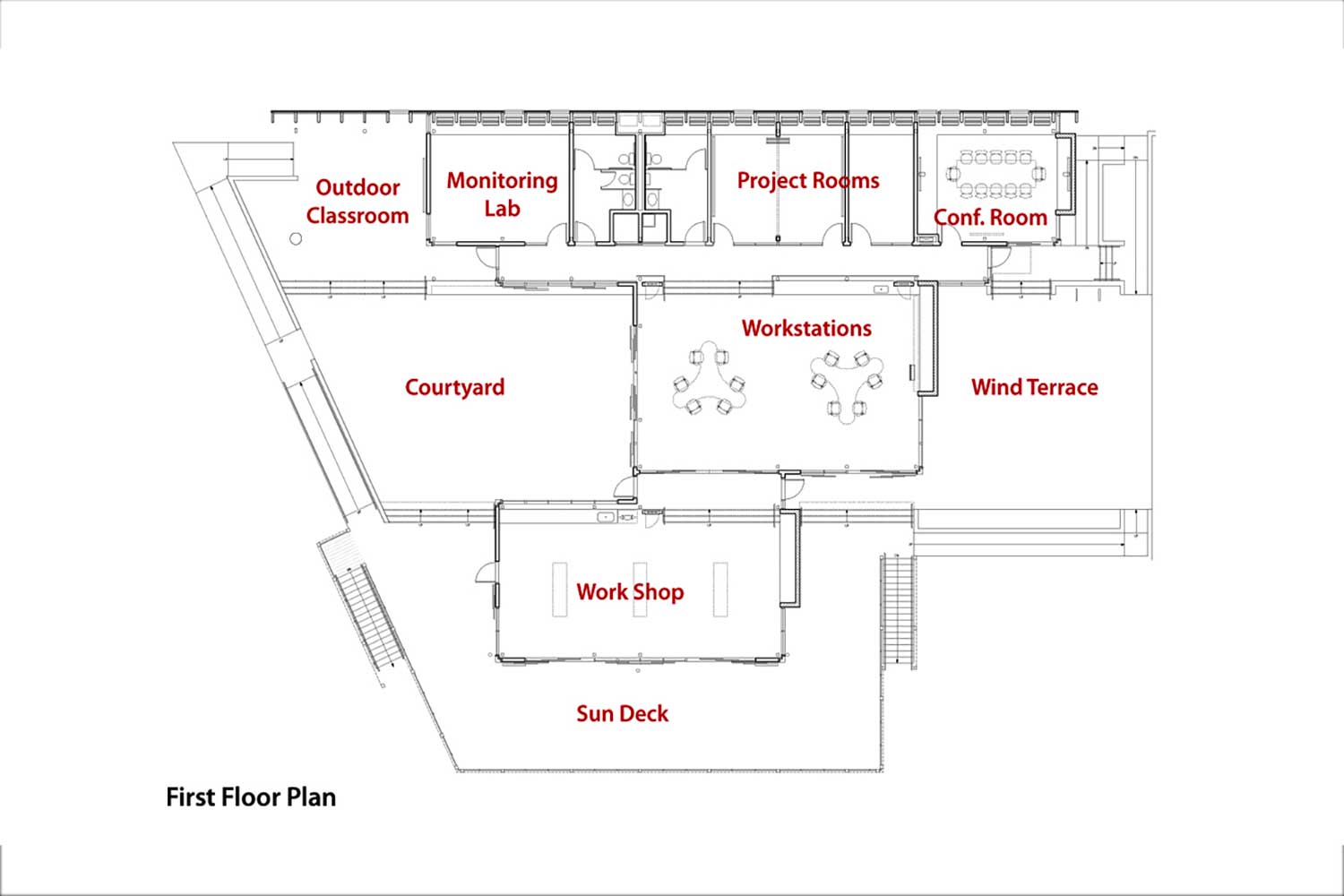

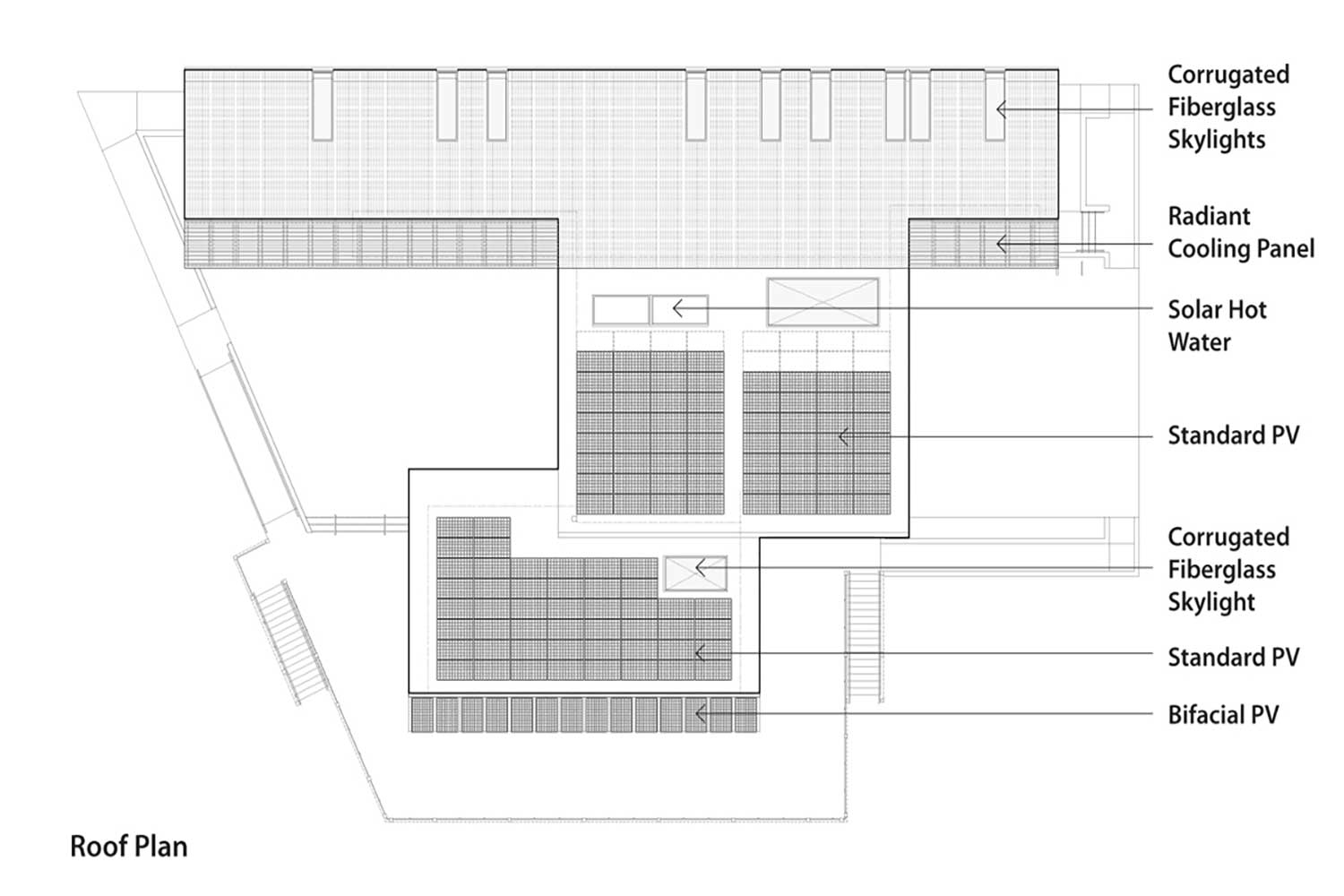

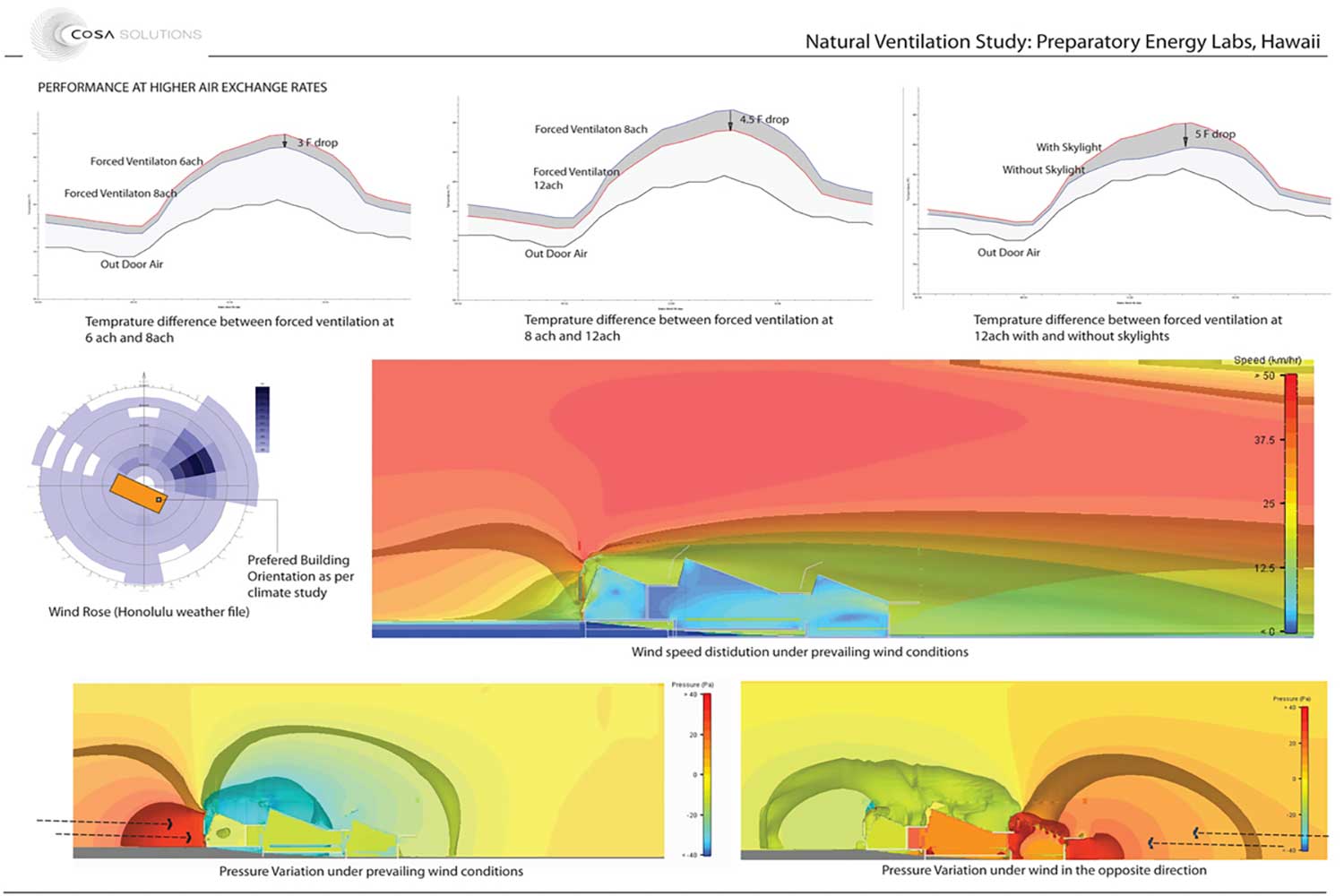

اگر بتوان مکانی را یافت که شرایطی آرمانی برای بنایی با صفر خالص انرژی و واکنشپذیری کامل نسبت به اقلیم داشته باشد، آن مکان همان سایتِ آزمایشگاه انرژیِ آکادمی آمادگی هاوایی (Hawaii Preparatory Academy) است. این تأسیسات به مساحت ۶۰۰۰ فوت مربع و هزینهی ۴٫۵ میلیون دلار، که توسط دفتر معماری فلنزبرگ (Flansburgh Architects) در بوستون طراحی شده، فضایی را برای پژوهش و گسترش فناوریهای تجدیدپذیر فراهم میآورد و در گوشهای از پردیس دبیرستانی خصوصی K–12 در شهر کاموئلا (Kamuela)، در دامنهی کوههای کوهالا (Kohala Mountains) قرار گرفته است. آنا سرا (Ana Serra)، همکار دفتر بیورو هپولد (Buro Happold) در نیویورک و مشاور پایداری پروژه، میگوید: «با وجود بادهای تقریباً بیشازحد نیرومند شمالی، این مکان از نظر تابش خورشید، بارندگی و رطوبت نسبی، منابع طبیعی فوقالعادهای در اختیار دارد.» آزمایشگاه انرژی در اکتبر موفق به دریافت گواهی LEED for Schools در رتبهی پلاتینیوم شد و در اواخر آوریل نیز گواهی کامل Living Building Challenge را بهدست آورد — سومین پروژه در جهان که به چنین افتخاری نائل میشود. برنامهی «چالش زیستساختمان» که توسط شورای ساختمان سبز کاسکادیا (Cascadia Green Building Council) تدوین شده و بهعنوان دشوارترین نظام گواهینامهی ساختمانهای پایدار شناخته میشود، الزام میکند که تمام نیازهای انرژی در محل، از منابع تجدیدپذیر تأمین شود و تمام آب مصرفی از بارش یا سامانهی بستهی بازچرخانی بهدست آید. این برنامه همچنین استفاده از مواد بالقوه سمیِ موجود در «فهرست قرمز» خود را ممنوع میداند — موادی که بسیاری از آنها در مصالح ساختمانی متداول یافت میشوند. علاوه بر آن، فاصلهی مجاز حملونقل مصالح تا محل پروژه را محدود میکند تا مصرف انرژیِ جابهجایی کاهش یابد. در مجموع، ۲۰ «ضرورت» یا پیششرط باید رعایت شود تا پروژه واجد عنوان «زیستساختمان» شود. بیل ویکینگ (Bill Wiecking)، مدیر آزمایشگاه انرژی، دشواری دریافت این گواهی را به «سفر به ماه» تشبیه میکند، در حالی که گواهی LEED را با مدالهای نقره، طلا و پلاتینیومش «بیشتر شبیه پیروزی در المپیک» میداند. برای بهرهگیری کامل از ظرفیتهای طبیعی زمین و تحقق اهداف پروژه، تیم طراحی طرحی متشکل از سه حجم باریک و کشیده ارائه کرد که با شیب زمین پایین آمده و رو به جنوب و مناظر گشوده میشوند. این احجام از مصالح و سیستمهای سازهای مشابه ساختمانهای دیگرِ پردیس تبعیت میکنند: دیوارهایی از تخته و نوارکوب، بتن درجا و بامهایی متکی بر تیرهای چوبی چسبخوردهی لایهای. بالاترین حجم که شکلی میلهمانند دارد، دارای بامی دوشیبه است که تا نزدیکی زمین خم میشود تا بادهای شدید شمالی را منحرف کند. دو حجم پایینتر زیر بامهای شیبدار ملایم با پیشآمدگیهای عمیق قرار گرفتهاند که فضاهای داخلی را از گرمایش بیشازحد محافظت میکند. افزون بر پناهدادن در برابر عوامل طبیعی، بامها سطحی برای تولید انرژی و گردآوری آب باران نیز فراهم میکنند. دو بام شیبدار در مجموع ۲۷ کیلووات ظرفیت تولید انرژی دارند و از سه نوع سامانهی فتوولتائیک (PV) بهره میبرند، از جمله یک آرایهی ۴ کیلوواتی از پنلهای دوسطحی که از نور بازتابی محیط نیز برق تولید میکنند. بارندگیهای جمعآوریشده روی بام، به مخزنی با ظرفیت ۱۰٬۰۰۰ گالن هدایت میشود که آب لازم برای شستوشوی دست، سیفون توالت، نظافت و آبیاری را تأمین میکند. از نظر فضایی، ساختمان برای پشتیبانی از آنچه رئیس فلنزبرگ، دیوید کرتو (David Croteau)، «یادگیری مبتنی بر پروژه» مینامد، سازماندهی شده است. بخش نخست شامل اتاقهایی است که دانشآموزان در گروههای کوچک ایدهپردازی میکنند، در حالی که دو بخش پایینی و بازتر آزمایشگاه شامل میزهای کار و کارگاه میشوند. در اینجا، دانشآموزان با ابزارهای شبیهسازی رایانهای طرحهای خود را تکمیل کرده و نمونههای فیزیکی میسازند. چندین سکوی باز نیز برای آموزش در فضای آزاد و آزمودن نمونهها تعبیه شده است. انواع گوناگونی از تحلیلها، از جمله دینامیک سیالات محاسباتی (CFD)، به تیم پروژه در بهینهسازی تهویهی طبیعی یاری رساندند. نتیجهی طراحی، مجموعهای از دهانهها بود که توسط سامانهی مدیریت ساختمان (BMS) کنترل میشوند. در لبهی شمالی ساختمان، دریچههایی زیر پیشآمدگی بام قرار گرفتهاند که هوای تازه را وارد میکنند، و در ارتفاع بالا نیز پنجرههای کلرستوری و دریچههای خروجی هوای گرم را بهواسطهی پدیدهی stack effect (اثر دودکشی) به بیرون هدایت میکنند — پدیدهای که با اختلاف فشار ناشی از وزش بادهای دامنهی کوه تقویت میشود. راهبردهای صرفهجویی و تولید انرژی بهاندازهای کارآمد بودهاند که در نخستین سال بهرهبرداری، ساختمان تنها اندکی بیش از نیمی از برق پیشبینیشده در مدل طراحی را مصرف کرد و ۲۵٬۲۸۵ کیلوواتساعت برق مازاد حاصل از پنلهای خورشیدی را به شبکهی برق پردیس بازگرداند (حدود ۶۰٪ از کل انرژی تولیدی). فنهای تخلیه که برای تقویت تهویهی طبیعی پیشبینی شده بودند، تاکنون نیازی به استفاده نداشتهاند. همچنین سیستم تهویهی مطبوع کمکیِ اسپلیت که برای خنکسازی تجهیزات حساس آزمایشگاهی در شرایط بحرانی تعبیه شده بود، هرگز مورد استفاده قرار نگرفته است. عملکرد بهتر از انتظار ساختمان را میتوان ناشی از چند عامل دانست. مهمترین آن، تفاوت میان ریزاقلیمهای محل ساخت و فرودگاه هیلو (Hilo Airport) است — جایی که وزارت انرژی آمریکا (DOE) دادههای اقلیمی تاریخی را برای شبیهسازیها جمعآوری کرده بود. اگرچه فرودگاه نزدیکترین ایستگاه به چنین دادههایی است، اما در ارتفاع تنها ۳۸ فوتی از سطح دریا و در ناحیهی ساحلی قرار دارد، در حالی که پردیس «هاوایی پرپ» حدود ۶۰ مایل دورتر و در ارتفاع بالاتر و درونسرزمین واقع شده است. اکنون، پس از بیش از یک سال جمعآوری داده از ایستگاه هواشناسی بام خودِ آزمایشگاه، روشن شده که شرایط واقعی سایت بسیار مساعدتر از دادههای DOE برای تهویهی طبیعی است. نظارت پیگیرانهی ویکینگ (Wiecking) نیز نقش چشمگیری در کارایی آزمایشگاه دارد. سامانهی مدیریت ساختمان (BMS) که او طراحی کرده، بر پایهی حدود ۶۰۰ حسگر توزیعشده در سراسر ساختمان عمل میکند که همهچیز از سطح دیاکسید کربن، دما و رطوبت گرفته تا تولید و مصرف انرژی را رصد میکنند. این سامانه کارکرد بسیاری از تجهیزات ساختمان را خودکار کرده و دادههای لحظهای دربارهی عوامل مختلف، از جمله میزان تولید و مصرف انرژی، در اختیار او میگذارد. حتی به او امکان میدهد تا وسایلی را که بهاشتباه روشن ماندهاند (مانند چاپگر یا لامپهای فرابنفش مورد استفادهی دانشآموزان در آزمایشها) شناسایی کند. اگرچه این سامانههای کنترلی بسیار پیشرفتهاند، اما بهگفتهی تیم پروژه، پرزحمتترین بخش کار نبودند. دشوارترین مرحله، یافتن مصالحی در محدودهی شعاع مجاز حملونقل برنامهی زیستساختمان بود که فاقد مواد ممنوعه باشند. کریس براون (Chris Brown)، معمار پروژه از فلنزبرگ، میگوید: «احتمالاً سه بار مشخصات فنی را بازنویسی کردیم.» یکی از نمونههای دشواری در انتخاب مصالح، پنلهای آکوستیکی مورد نیاز برای الزامات LEED for Schools بود. تنها پنلهای آمادهی عرضه از تأمینکنندگان محلی حاوی فرمالدهید یا مواد ضدحریق بودند. بنابراین پیمانکاران برای حل این مشکل، پنلهایی از چوب محلی، الیاف پنبهی بازیافتی و پارچهی کنفی ساختند. با توجه به همهی تلاشهای انجامشده برای کسب همزمان دو گواهی Living Building و LEED، نکتهای شگفتآور آن است که معماران بر این باورند که آزمایشگاه انرژی، دستکم در نگاه نخست، چندان «سبز» به نظر نمیرسد. کرتو میگوید: «این بنا فریاد نمیزند که من پایدارم؛ بلکه فقط معماریِ واقعی است — متناسب با اقلیم و بافت خود.»

Hawaii Prep’s Energy Lab is enclosed within three linear, board-and-batten-clad volumes, each with a discrete roof, that step down the terraced site.

If any location offers ideal conditions for a net-zero, fully climate-responsive building, it’s the site of the Hawaii Preparatory Academy’s new Energy Lab. The $4.5 million, 6,000-square-foot facility, designed by Boston-based Flansburgh Architects, provides space for the study and development of renewable technologies, and sits at one corner of the private K–12 institution’s upper-school campus in Kamuela, at the foot of the Kohala Mountains. With the exception of almost too-strong winds from the north, it offers excellent “resources” in terms of sun, precipitation, and relative humidity, says Ana Serra, an associate in the New York office of Buro Happold, the project’s sustainability consultant. The Energy Lab received a LEED for Schools Platinum rating in October, and in late April achieved full Living Building Challenge certification—only the third such project to do so. The “Challenge,” a program developed by the Cascadia Green Building Council and widely regarded as the most demanding green building certification system, requires that energy needs be satisfied on-site from renewable sources and that all of its water come from precipitation or from a closed-loop system. The program also prohibits the use of the potentially toxic substances on its “red list,” many of which are commonplace in construction materials. In addition, it places limits on the distance from which products can be shipped in order to reach a building site. In all, 20 “imperatives,” or prerequisites, must be met for a project to be designated as “living.” Bill Wiecking, the Energy Lab’s director, compares the difficulty of Living Building certification with going to the moon. But LEED certification, with its Silver, Gold, and Platinum plaques, “is more like winning the Olympics,” he says. To make the most of the site’s natural assets and satisfy the project’s goals, the team developed a scheme made up of three long and narrow volumes that step down with the landscape and open to views to the south. These volumes echo the materials and structural systems of buildings elsewhere on campus: They have walls of boards and battens and poured-in-place concrete and roofs supported by wood decking spanning glue-laminated beams. The uppermost barlike element has a double-pitched roof canted so that it nearly touches the ground and deflects the strong wind from the north. The two lower volumes are sheltered under gently sloping shed roofs with deep overhangs that shield the interiors from heat gain. In addition to providing shelter from the elements, the roofs also provide surfaces for energy production and rainwater collection. The two shed roofs incorporate 27 kW of generating capacity, with three types of photovoltaics (PV), including a 4 kW array of bifacial panels (a type of PV in which the back face generates electricity from ambient light reflected off surrounding surfaces). The precipitation that falls on the roofs feeds a 10,000-gallon storage tank that provides water for hand washing, toilet flushing, janitorial needs, and irrigation. Spatially, the building is organized to support what Flansburgh president David Croteau calls “project-based learning.” The first zone is divided into rooms where students develop ideas in small teams, while the two more open, lower parts of the lab house workstations and a workshop. Here they refine their concepts with computer simulation tools and build physical mockups. Several decks provide space for outdoor instruction and prototype testing. Various types of analyses, including computational fluid dynamics, helped the project team optimize the design for natural ventilation. The resulting configuration has a series of openings controlled by the building management system (BMS) with louvers tucked under the low-level overhang at the building’s north edge that let in fresh air. High-level louvers and clerestory windows allow spent air to escape via the stack effect, a phenomenon assisted by the pressure differential created when the mountainside winds waft over the roof. The energy-conservation and -generation strategies have proved so effective that in the first year of operation, the building consumed only a little more than half of the power predicted by the design team’s model, and exported 25,285 kWh of electricity produced by the PVs to the campus grid (about 60 percent of the power generated). Exhaust fans, intended to augment the natural ventilation scheme, have so far not been needed. And a backup split air-conditioning system, included in the building primarily to keep sensitive lab equipment cool in extreme conditions, has also never been used. Several factors account for the building’s even-better-than-expected performance. The most important is a difference between the microclimates at the building site and at Hilo Airport—the location where the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) collected the historical weather data used in the simulations. Although the airport is the closest site with such information, it is situated at 38 feet above sea level and on the coast, while the Hawaii Prep campus, about 60 miles away, is at a much higher elevation and further inland. Now that the energy lab has been open and collecting data from its own rooftop weather station for more than a year, it is clear that the actual conditions at the site are much more favorable for natural ventilation than the DOE data indicates. Wiecking’s vigilance also plays a significant role in the lab’s efficiency. The BMS, which he designed, depends on about 600 sensors distributed throughout the building that monitor everything from CO₂ levels, temperature, and humidity to power generation and consumption. It automates the operations of many of the building’s systems and gives Wiecking real-time information about such factors as energy generation and use. It even allows him to identify specific equipment that has been left on mistakenly, such as a printer or the UV lamps that students use for experiments. Although these controls are extremely sophisticated, they were hardly the most effort-intensive part of the project, according to the team. Instead, the task presenting the biggest challenge was finding materials from within the Living Building program’s allowed transportation radius that were free of prohibited substances. “We must have rewritten the specs three times,” says Chris Brown, Flansburgh project architect. One illustration of the difficulty surrounding materials selection is the acoustic panels needed to satisfy LEED for Schools requirements. The only off-the-shelf panels from nearby suppliers contained formaldehyde or flame retardant. So, to solve the problem, the contractors built their own from locally available wood, recycled cotton core material, and hemp canvas. Given all the effort involved in meeting the requirements for both Living Building and LEED certification, it is somewhat surprising that the architects like to point out that the Energy Lab, at least at a quick glance, doesn’t seem overtly green. “It doesn’t scream ‘sustainable building,’” says Croteau. “It is just real architecture, appropriate to its climate and its context.”

مشخصات کلیدی (Key Parameters)

موقعیت: کاموئلا، هاوایی (دامنههای کوه کوهالا)

زیربنا: ۱۲٬۰۰۰ فوت مربع (۱٬۱۱۵ متر مربع) شامل ۶٬۰۰۰ فوت مربع (۵۵۷ متر مربع) فضای بسته و ۶٬۰۰۰ فوت مربع (۵۵۷ متر مربع) فضای باز

هزینه: ۴٫۵ میلیون دلار

تاریخ تکمیل: ژانویه ۲۰۱۰

مصرف سالانهی انرژی خریداریشده (بر اساس اندازهگیری واقعی): صفر؛ ۱۰۰٪ کاهش نسبت به حالت پایه

ردپای کربن سالانه: منفی ۵٫۸ پوند CO₂ بر فوت مربع (منفی ۲۸٫۶ کیلوگرم CO₂ بر متر مربع)

برنامهی عملکردی: فضاهای پروژهی قابل تقسیم، ایستگاههای کاری تطبیقپذیر، آزمایشگاه، اتاق مانیتورینگ، دفتر مدیر و اتاق کنفرانس

تیم طراحی و اجرا (Team)

کارفرما: آکادمی آمادگی هاوایی (Hawaii Preparatory Academy)

معماران: فلنزبرگ آرکیتکتز (Flansburgh Architects)

نمایندهی کنترل کیفیت و بهرهبرداری: گرین بیلدینگ سرویسز (Green Building Services)

مهندسان:

بِلت کالینز هاوایی (Belt Collins Hawaii Ltd.) – عمران

والتر ورفِلد و اسوشیتس (Walter Vorelfeld & Associates) – سازه

هاکالائو انجینیرینگ (Hakalau Engineering, LLC) – مکانیک

والِس تی. اوکی، پی.ای. (Wallace T. Oki, PE, Inc.) – برق

مشاوران: بیورو هپولد (Buro Happold Consulting Engineers) – پایداری

مدیریت پروژه: پاهانا اینترپرایزز (Pa‘ahana Enterprises LLC)

پیمانکار اصلی: کوالیتی بیلدرز (Quality Builders, Inc.)

منابع و مصالح (Sources)

سیستم سازهای: کالورت کمپانی (Calvert Company Inc.)

تیرهای چوبی چسبخورده از نوع داگلاس فیر (Douglas Fir)

پنجرهها: بریزوی آلتایر لوورد (Breezeway Altair Louvered)

شیشه: پیپیجی سولاربان ۶۰ عایقدار (PPG Solarban 60 Insulated)

درها: سیستم در و نمای آلومینیومی ساوتوست (Southwest Aluminum Storefront & Door System)

رنگها و پوششها: شروین-ویلیامز (Sherwin-Williams)؛ سیفکوت (Safecoat)؛ دوراستِین (Durastain – چوب سِدار)

کفپوش و کاشی دیوار: سونُما تایلمیکرز (Sonoma Tilemakers)

فرش: بنتلی پرینس استریت (Bentley Prince Street)

نورپردازی: الیپتیپار (Elliptipar)

پردهها: مِکوشِید (MechoShade)

KEY PARAMETERS

Location: Kamuela, Hawaii (Kohala Mountain foothills)

Gross area: 12,000 ft² (1,115 m²): 6,000 ft² (557 m²), enclosed; 6,000 ft² (557 m²), exterior

Cost: $4.5 million

Completed: January 2010

Annual purchased energy use (based on metered usage): 0.0; 100% reduction from base case

Annual carbon footprint: -5.8 lbs. CO₂/ft² (-28.6 kg CO₂/m²)

Program: Subdivisible project rooms, adaptable workstations, laboratory, monitoring room, director’s office, and conference room

TEAM

Owner: Hawaii Preparatory Academy

Architects: Flansburgh Architects

Commissioning agent: Green Building Services

Engineers: Belt Collins Hawaii Ltd. (civil); Walter Vorelfeld & Associates (structural); Hakalau Engineering, LLC (mechanical); Wallace T. Oki, PE, Inc. (electrical)

Consultants: Buro Happold Consulting Engineers (sustainability)

Project management: Pa‘ahana Enterprises LLC

General contractor: Quality Builders, Inc.

SOURCES

Structural system: Calvert Company Inc.

Douglas Fir glue-laminated beams

Windows: Breezeway Altair Louvered

Glazing: PPG Solarban 60 Insulated

Doors: Southwest Aluminum Storefront & Door System

Paints and stains: Sherwin-Williams; Safecoat; Durastain (cedar)

Floor and wall tile: Sonoma Tilemakers

Carpet: Bentley Prince Street

Lighting: Elliptipar

Blinds: MechoShade

مدارک فنی