آرتور آپهم پوپ اهمیت و خصلت هنر ایرانی

هفتمین کتاب سال معماری معاصر ایران، 1403

آرتور پوپ معتقد بود : "هنر ایرانی هدیهی جاویدان ملت ایران به جامعهی جهانی بوده است… آخر اینکه، هنر ایران مدرک و سابقهای و تفسیر و تعبیری است بازمانده از ملتی که از کهنترین زمانها نقش موثری در تاریخ جهان بازی کرده است. نقش ایران در آسیا تعیین کننده و در اروپا مهم بوده است. معنای زندگی تاریخی این کشور هنوز چنان که باید روشن نشده است؛ اما ژرفترین خصلت و پرمعنیترین آرمانهای او در هنرهایش تحقق و تجسم یافتهاند آن هم با شیوایی و استحکامی که در کمتر سند دیگری میتوان یافت".

هنر ایرانی یک پدیدهی تاریخی حائز اهمیت قدر اول است. به نظر میرسد که اساسیترین و شاخصترین مشغلهی اقوام ایرانی پرداختن به هنر بوده است. کاملترین سابقهای که از زندگی این مردم بازمانده است، و ارزندهترین سهمی که در تمدن جهانی داشتهاند همین هنر است و تاریخ هنر آنان بسیاری از مسائل تاریخ فرهنگ بشری را روشن میکند. در آن نخستین تمدن بشری که بیش از شش هزار سال پیش در فلات ایران پدیدار شد هنر یک عنصر اساسی بود که در همهی دورههای بعدی هم نقش حیاتی برعهده داشت و در سراسر این مدت ویژگیهای مشخص و بارز خود را حفظ کرد. این هنر که در همان مراحل نخستین به مرتبهی بلندی رسیده بود توفیق یافت که در زمینههای بسیار و به شیوههای گوناگون که در عین حال ارتباط ذاتی و سازوارهای ارگانیک با هم دارند سلسلهی طویلی از شاهکارهای هنری بیافریند.

نبوغ و روح خاص ایران کاملترین تجسم خود را در هنرهای به اصطلاح تزیینی به دست آورده است؛ یعنی هنرهایی که راز تاثیر آنها در زیبایی نقش و طرح نهفته است. در این رشتهها ایران به تسلطی رسید که در طول بیمانند تاریخ فرهنگ این سرزمین کمتر تزلزلی بدان راه یافته است. این قریحه و استعداد آراستن و تزیین در همهی آفرینشهای هنری ایران تابان است. مردم ایران گویی بر حسب مفاهیم تزیینی میاندیشند زیرا همین روشنی و دقت طرح و وزن در شعر و موسیقی آنان نیز دیده میشود.

به راستی اهمیت خاص هنر ایرانی در این است که معتبرترین نمایندهی این نظر است که غرض نخستین هنر، بازنمایی نیست، بلکه تزیین و زینتبخشی است. این اصل در بسیاری از آثار هنری آسیا رعایت میشود و در بعضی از دورههای هنر اروپایی هم دیده میشود؛ به خصوص در دورههایی که اروپا در تماس نزدیک با مشرق زمین بوده است. از طرف دیگر هنر آسیایی هم در لحظاتی بازنمایی را به منزلهی هدف خود پذیرفته است. اما، به طور کلی این دو دیدگاه با هم تعارض دارند و بر نظریههای متفاوتی دربارهی ماهیت واقعیت و رابطهی انسان با آن بنا شدهاند. با این همه این دو نوع هنر با یکدیگر ناسازگار نیستند، زیرا که در نمونههای عالی هر هنری هر دو جنبه رعایت میشود؛ گیرم که نسبت آنها برحسب روح فرهنگ مورد بحث کم و زیاد میشود. در ایران اصل تزیین اقتدار خود را بسیار بهندرت تنزل داده است.

در هنر ایران کمابیش در همهی دورهها این شور و اشتیاق شدید به تزیین با مهارت فنی کامل و قوهی ابداع فراوان تحقق و تجلی یافته است. برای کهنترین سفالینههای منقوش با تمام مقدوراتی که از جهت فنی در سدههای بعد پرورانده شده است مشکل بتوان نظیری یافت. این سفالینهها با آن نازکی شکنندهی واهمهانگیز و همواری و ظرافت دلپذیر پوشیده است از نقشهایی که با کمال مهارت برای هر ظرفی طراحی شده است و کیفیت بدیع و حالت زندهی آنها چشم را خیره میکند و کهنترین آثار سرامیک جهان هنوز به یک معنی بهترین آنها به شمار میرود. درست است که هنر سفالگری از عهد هخامنشی تا پایان دورهی ساسانیان میلنگد، این هنر در سدههای نخستین اسلامی از نو شکوفا میشود. از لحاظ شیوایی، شکل زیبایی و تنوع رنگ، حالت زنده و گیرایی و تناسب آرایهها، ظرفهای ایرانی آن دوران، هنر سفال لعابدار را به مدارج تازهای از کمال میرسانند. همین چیرهدستی در آفرینش آرایههای گوناگون همه شیوا و خوش ترکیب و آراسته به رنگهای هماهنگ همراه با ظرافت ساخت و مهارت فنی، پیروزی مشابهی را برای انواع مصنوعات دیگر در امکان آورد. چنین بود که تمامی امکانات فرشبافی به کار گرفته شده و در نساجی کیفیتهایی به دست آمد که اهم از هر مقایسهای سربلند بیرون میآید. به علاوه این استعدادها در همهی هنرهای دیگر و حتی در صنعت موثر افتاد. چیزی نبود که انسان بسازد یا به کار برد و به صرافت طبع صورت زیبایی به خود نگیرد: از باغ و نوشته گرفته تا جنگافزار و لباس و اثاث خانه؛ در ساختن اینها همان دقت و زحمتی صرف میشد که در کار هنرهای به اصطلاح مهم معمول بود. خلاصه اینکه هر جا مادهای بود که بتواند صورت زیبایی به خود بگیرد یا رنگی که بتواند ترکیبی بپذیرد یا چیزی که بتواند حامل نقشی باشد آنجا را ایرانیان میدانی برای جولان دادن تخیل و ذوق خود میساختند.

تزیین و بازنمایی

اما، امر تزیین یک عمل بیواسطه و نهایی نبود. قریحهی بازنمایی، هم گرچه به همان اندازه اساسی نبود، باری در صحنه حضور داشت و نه تنها از نفس نمیافتاد بلکه با اقتدار هنر تزیینی در میافتاد؛ در حالی که این هنر برتری خود را در میدان رقابت و پس از پیمودن سایر راههای بیان هنری به دست آورده بود. حتی پیکرسازی، گرچه در ایران محدود بود و منع شرعی داشت، در این سرزمین تاریخ طولانی و ممتازی دارد. با این حال هنرهای بازنما عموما حرمت روح تزیین کار ایرانی را نگاه میداشتند؛ به طوریکه طرح و صورت محض در این هنرهای ملموستر و شاملتر نفوذ میکرد و راهنمای آنها میشد. از اوان هزارهی سوم پیش از مسیح، پیکرسازان به ساختن پیکرههای جانوران میپرداختند، که هر چند صورت تزیینی داشت ولی با نوعی شناخت دقیق زیبایی موضوع کار و حس پیکرسازی واقعی همراه بود. در آغاز هزارهی دوم، پیکرهای ریختگی مفرغی جانوران از صفحات غربی و شمال غربی ایران بازنمایی طبیعی قانعکنندهای را در طرحهای متناسب و گیرا نشان میدهند. در حدود همان زمان پیکرسازان از عهدهی آزمایش سختتری در شبیهسازی برآمدند و با همان دریافت تیزبینانهای که از هستی جانوران داشتند و آنان را در ساختن پیکرهی آنها کامیاب ساخته بود، به ساختن سرهای مفرغی انسان پرداختند که در آنها شخصیت بارز و قوت عاطفی گیرایی به چشم میخورد. پیکرسازی هخامنشی عالیترین سابقهی نبوغ ایرانی را در ترکیب متعالی صورت محض و بازنمایی نشان میدهد. در نقش موجودات زندهای که ذرهای از کیفیت طبیعی خود را فدای کلیت نوعی نمیکنند، اصول طراحی انتزاعی چنان مخلد گشته است که گویی عین قوانین فراست و هوشمندیاند و از دل طبیعت ذهن بیرون آمدهاند. در دورهی حکومت پارتها با وجود تماس با یونان، علاقهی ایرانیان به ساختن پیکرههای بزرگ تقریبا از میان رفت و علت آن شاید احساس حقارتی بوده است که در قیاس با توان فنی و کمال واقعگرایی صنعتگران، یونانی به پیکرسازان ایرانی دست میداده است اما در زمان ساسانیان همان سنتهای ملی دیرین در دین و سیاست و هنر از نو زنده شدند و پیکرسازی بار دیگر خود را بازیافت. بی گمان، پیکرتراشان ایرانی از روی نمونههای رومی کار میکردند یا شاید هم از صنعتگران رومی کمک میگرفتند؛ ولی آن صحنههای حماسی که از دل کوه درآوردهاند عالی ترین لحظات را در زندگی شاهان سلسلهای که مدعی اقتدار آسمانی بود به روشنی نشان میدهد و در عین حال آن تعلق خاطر دیرین را به صورت کار نگه میدارد و تجدید میکند. و یک بار دیگر توازن انداموار روابط منتظم و حرکت موزون خطها و سطحها تثبیت وجود هنر بازنمایی را ممکن میکند. هر چند روی چند بشقاب نقره به راستی گرانقدر یا روی برخی از نمونههای مفرغی، نوعی واقعگرایی بسیار زنده دیده میشود ولی اینها هم کیفیت تزیینی خود را دارند و تاثیر آنها، که انتخاب درست و تاکید بجا آن را تقویت میکند خصلت عاطفی پرقدرتی را پدیدار میکند. در دورهی اسلامی، پیکرسازی، با آن که به واسطه منع شرعی مورد بیمهری است به کلی از میان نمیرود؛ شیرهایی که در پایههای کاخ چهلستون روبه روی هم نشستهاند خاطراتی را به یاد میآورند که دست کم به دورهی ساسانیان باز میگردد.

نقاشی مینیاتور

نقاشی که دقیقترین و شاملترین رشتهی هنر است و کارمایهی آن تمام جهان مرئی را دربر میگیرد، به ویژه در معرض این وسوسه قرار دارد که انضباط صورت را از دست بگذارد و تسلیم وسوسه بازنمایی محض گردد؛ ولی نقاشی ایرانی با آنکه تمام جهان در برابرش گسترده بود و او را به تسخیر زمینهای دعوت میکرد که در پرتو مهارت فنی و دستاوردهای بعدی مقدور مینمود به همان الهام نخستین خود وفادار ماند و نوع خاصی از هنر تزیینی و تصویری به وجود آورد.

آثار بزرگ هنر نقاشی در همه زمانها و مکانها توجه بسزایی به شکل و صورت (فرم) داشته است، و نقاشی چه در خاور دور و چه در اروپا بیش از نقاشی ایرانی به اختراع انواع ترکیببندی توفیق یافته است؛ اما نقاشی ایرانی مانند سایر هنرهای ایرانی با جدیت بیشتری به آرمانهای انتزاعی خود وفادار مانده است. تزیین، برتری خود را بر بازنمایی حفظ کرد از معنی و زیبایی عناصر آرایشی محض با همدلی بیشتری بهرهبرداری شد و این وجوه به درجه بالاتری از کمال رسیدند. این عناصر فرع کار به شمار نمیرفتند، بلکه جزو ذات نمایاندن و تجسم بودند و چنان اقتداری اعمال میکردند که طفره رفتن از آن ممکن نبود. اما، با آن که نقاشی به این ترتیب موافق همان دیدگاهی است که از زمان زایش هنر در فلات ایران حاکم بود، مفهوم شکل و صورت پهنا و ژرفای بیشتری یافته بود در حقیقت زیبایی نقش را مخیلهای که فراتر از عالم محسوسات پرواز میکرد دیگرگون ساخته و به مرتبهی بالاتری ارتقا داده بود. وضوح، دقت و درخشش جواهر مانند جزئیات با نوعی بینش ترو تازه شاعرانه همراه شده بود که گویی از جهان دیگری بشارت میدهد. واقعیت مشخص با تخیلی زنده و بغرنج درهم میآمیزد بینشهای عرفانی، که به چشم این مردم شاعر منش واقعی و بیواسطه مینماید چه در زبان و چه در هنر تذهیب جامهی ملموسی به تن میکند. تجلی فر و شکوه آسمانی، که بسیار روی میدهد همواره همراه با وضوح است و صور و ترکیب بندهایی که به کار می رود غالبا با کارمایه اثر تناسب دارد و همین امر قوت عاطفی این کارمایه را بسیار بیشتر میسازد. اینجا ما حرکت و هیجان عشق و ماجرا، حساسیت متعالی و حالت خلسه را به چشم میبینیم.

معماری

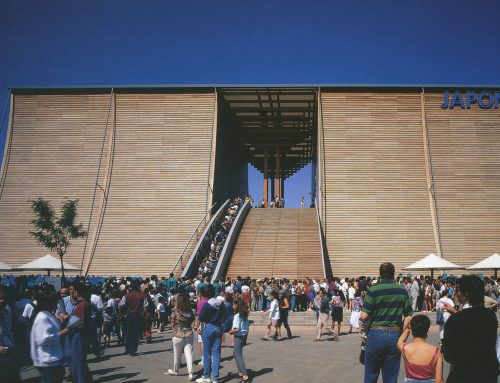

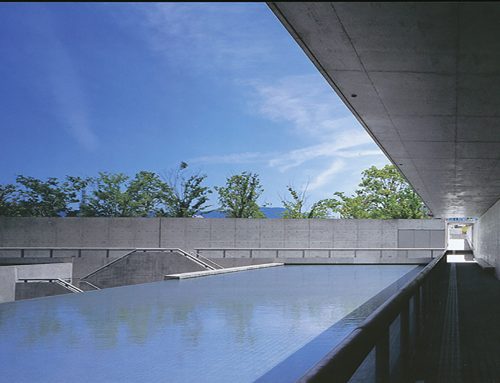

در معماری که صورت پذیرترین هنرهای بصری است و شاید دشوارترین محک اصالت و ظرفیت زیبایی شناختی باشد، ایران برای تجسم آرمان خود مجال و محل کافی یافته است و دستاورد او در این زمینه که دستاورد قابلی است با توفیق یکسان به چند دوره تقسیم میشود ایرانیان اشکال و اسلوبهای هنری خاصی را اختراع کردند و کمال بخشیدند که آنان را به پروراندن نوعی معماری قادر ساخت که ابهت، سادگی، و حجم گویای آن شایان توجه است این حجم را ایرانیان با پوستهی پرمایه و درخشانی پوشاندند. در دورههای آغازین در بناهای سبک ستوندار چوب فراوان به کار میرفت، اما بعدها بازتاب این سبک را در ستونهای سنگی تخت جمشید میبینیم ، اما معماری گنبددار و طاقدار هم کمابیش به همان قدمت است و در این معماری است که مقدورات نهایی آجر به فعل میآید.

این دو سبک در کنار یکدیگر پرورانده شدند؛ بدانسان که یکی اشتیاق به بلندی و باریکی را تحریک و ارضا میکند و دیگری بر همان روال عطش ستایش شکل سه بعدی سنگین را به عنوان بیان موثر قدرت فرو مینشاند. در سدههای نخستین اسلامی این دو خط در هم آمیخته ، هماهنگی پیروزمندانه شاهکاری به وجود می آورند که تجسمی است از منطق منسجم و در عین حال زلال و زیبا محکم ولی سُبک، مقتدر ولی انسانی؛ یعنی گنبدخانهی شمالی مسجد جامع اصفهان. اما، این یک مورد است از بیش از دوازده شاهکار موجود، گرچه زیباترین آنهاست؛ و این شاهکارها که تنها بازماندهی نوع خود هستند باید نمایندهی تعداد زیادی نظایر از میان رفته باشند این بناها نشان میدهند که حس صورتشناسی ایرانیان چه ژرفایی داشته که تا در بناهای عظیم تجسم نمییافت ارضا نمیشد در این بناها به جای نمایش کارورزی، نیروهای سازوارهای فضا برای بیان عواطف به زیبایی ترکیببندی شده است.

گسترش هنر ایرانی

عقلانیت و فایدهی عملی انواع فکرها و صناعتهایی که ایران ابداع کرد یا پروراند زیبایی ذاتی هنرهای او و صورتهای روشن و قابل فهمی که در بیان این هنرها به کار رفته است گسترش وسیع آنها را مسلم میساخت و موقعیت ایران در کانون فرهنگ آسیایی نیز این گسترش را تسهیل میکرد. در حقیقت ایران زمانی با همهی تمدنهای بزرگ جهان در تماس بوده است و اندیشههای ایرانی را به همهی آنها میرسانده؛ ولی در عین حال از همهی آن تمدنها هم تاثیر میگرفته و الهامات بسیار متفاوت را آزادانه، اما با دید انتقادی، جذب میکرده است.

نقش ایران در معماری، روز به روز بیشتر شناخته میشود، سبک رومی از لحاظ ساختار و تزیین، هر دو متاثر از ایران است و شواهد جالبی حکایت از این میکند که معماری گوتیک هم ممکن است از جهت بعضی از اشکال اساسی ساختاری به ایران مدیون باشد. این که گرایش گوتیک در کیفیت تجسمی و شکل عمودی خود از شرق مایه گرفته است، بسیار محتمل به نظر میآید؛ و در مجموعه تاثیراتی که به واسطهی بازرگانان و مسافران و در جنگهای صلیبی به اروپا منتقل شد نگارههای ایرانی سهم مهمی داشتند.

در اهمیت هنر ایرانی برای هنر اروپایی مشکل جای مناقشهای باشد؛ هر چند ارزیابی دقیق این امر محققان را سالها مشغول خواهد داشت. هنر یونان و روم باستان (هنر) (کلاسیک در پایان عمر خود به ایران ساسانی پناه برد و در آنجا بود که گنجینهی تزیینات آن از نو به قالب ریخته شد و جان تازه گرفت تا باز به اروپا صادر شود. از راههای گوناگون دادوستد میان روسیه و اسکاندیناوی و مسیرهای دریای مدیترانه هنرهای تزیینی ایران در اروپا تاثیر داشتهاند و هرگاه هنر اسلامی به طور کلی با اروپا تماسی گرفته یا چیزی را القا کرده، آنجا روح ایرانی نافذ بوده است.

در این ضمن اقوام کمتر پیشرفتهی پشت مرزهای شمالی و شرقی، ایران گروههایی که بیشتر کوچ نشین بودند ولی با بعضی هنرهای ایرانی آشنایی داشتند و به واسطهی سهم بردن از سرمایهی سنتهای عام ایرانی بسیاری از کیفیتهای روح ایرانی در آنها دیده میشد فرهنگ ایرانی را به بیرون مرزهای ایران انتقال و آنجا گسترش میدادند. زیرا که این اقوام سکاها و سرمتیها و فرهنگهای آنها به یک معنای بسیار اساسی در مدار ایران قرار داشتند و شاید همچنان که پارهای از محققان عقیده دارند از لحاظ نژاد و زبان با مردم فلات ایران خویشاوند بودند، این اقوام بسیاری از مشخصات سبک هنری و شیوه تصویرگری و حتی فولکلور خود را به گوتها و ویزیگوتها و برخی دیگر از قبایل بربر منتقل کردند و این مایهها پس از انتقال به اروپا یکی از عوامل اصلی هنر پیش از عصر شارلمانی را به وجود آوردند و در اروپای اوایل قرون وسطی رسوبی از نقش و معنی برجا گذاشتند

از دهها قرن پیش، ایران در آسیا نیروی موثری بود. دلایلی در دست است که در پدیدآمدن اصل هنر در بینالنهرین انگیزشهایی که خاستگاه آنها فلات ایران بود نقش قاطعی داشتهاند. رشتههای همبستگی با هندوستان به پیش از هجوم آریاها برمیگردد، و نوعی یگانگی را تایید میکند که از تفاوتهای میان روحیات ژرفتر است. آثار نفوذ ایرانیان در هندوستان که در دورههای هخامنشی و ساسانی آشکار بود، در حدود سال ۱۰۰۰ میلادی و نیز با هجوم افغانها تجدید شد زیرا باید به یاد داشته باشیم که افغانها ایرانی بودند و عناصر فرهنگ ایرانی را با خود میبردند در زمان پادشاهان گورکانی مغولهای هند، نفوذ ایرانیان تا چندی در سراسر هندوستان غالب بود و در این دوره دربار و اشراف در زمینه فرهنگ از ایران الهام میگرفتند.

دادوستد میان ایران و خاور دور مداوم و پیچیده و دراز مدت بود. در هنرهای تزیینی سبک و روند کار و نیز انواع صناعتهای عملی در این میان رد و بدل میشد. بهعلاوه، فرهنگ ایرانی شکل نخستین آیین بودایی را دگرگون کرد زیرا که این آیین در مسیر رسیدن به چین از قلمروهای ایرانی میگذشت و اندیشههای دینی گوناگونی را به ویژه از سرچشمهی آیین مهر (میترا) جذب میکرد که سرانجام به صورت کیشهای معروف به آمیدا در میآیند.

اهمیت کلی تاریخ هنر ایران

از آنجا که ایران به این ترتیب در پرورش فرهنگهای دیگر در شرق و غرب عمیقا نقش داشت، مورخان هنرهای ملل دیگر باید از تاریخ هنر ایران کسب روشنایی کنند اما چند مسئله دیگر هم در این ضمن روشن میشود. هنر ایران به واسطهی قدمت طول عمر و دوام کیفیت اعلا به عنوان مرحلهای در کل تاریخ فرهنگ حائز اهمیت است. از آنجا که در فلات ایران پرورش هنرهای بسیار پخته با ظهور نخستین تمدن پیشرفته همراه است به کمک این هنرها میتوان معلوم کرد که انگیزهی زیباییشناسی انسان تا چه حد ازلی و دیرین و بنیادین است و خصلت و کارکرد و ارزش آن در بقای انسان چگونه است. بررسی تولید هنری با یک چنین دوام و بقایی نشان میدهد که چه انگیزههای عمدهای در پشت آن نهفته است و ماهیت فردیت هنری را هم برای ما روشن میکند در این منطقه دین بر زایش هنر نظارت داشته و به نحوی حیات آن را تا دوره پختگی حمایت میکرده است. از همین رو دین رابطهی پرمعنای میان این دو مشغلهی اساسی و مرکزی انسان را که هنوز هم کاملا روشن نشده است نشان میدهد، رابطهی میان هنر و شعر هم به همین نحو روشن میشود. زیرا که در ایران این دو رشته مدتهای مدید به یکدیگر وابسته بودهاند و از این حیث به هنرهای تصویری و شعر در چین شباهت داشتهاند زیرا که ایرانیان در طول قرنهای متمادی ملتی شاعر پرور بودهاند و از هنروران خود نه تنها میخواستهاند که حکایتهای نقل شده در ادبیات فارسی را تصویر کنند بلکه از آنها انتظار داشتهاند که نحوههای خاص تفکر و احساس شاعرانه را هم مجسم سازند. نقل شعر به سایر ابعاد زیباییشناسی وجوه تازه و جالبی از انگیزههای شاعرانه را روشن میکند و غلبهی آن را بر انواع تلاشهای آفرینشی نشان میدهد. هنر ایرانی با ریاضیات هم کمابیش نظیر همین روابط را دارد ایرانیان قرنها تفکر ریاضی داشتند و در برخی از اصول طراحی ایرانی مسلما اشکال معینی از تفکر ریاضی دیده میشود. همچنین سیر هنرها و صنایع هنری ایران نشان دهندهی نقش مهمی است که جغرافیا در تعیین خصلت و فعالیت ملل بازی میکند؛ هر چند در این باره بحث بسیار شده و هنوز تا حدی تاریک مانده است. تغییراتی هم که با حفظ وحدت خصلت، در طول تحولات اجتماعی فراوان صورت گرفتهاند میتوانند مسئلهی مناسبت میان فرهنگ زیباییشناختی و زمینههای سیاسی و اقتصادی آن را روشن کنند.

آخر اینکه، هنر ایران مدرک و سابقهای و تفسیر و تعبیری است بازمانده از ملتی که از کهنترین زمانها نقش موثری در تاریخ جهان بازی کرده است. نقش ایران در آسیا تعیین کننده و در اروپا مهم بوده است. معنای زندگی تاریخی این کشور هنوز چنان که باید روشن نشده است؛ اما ژرفترین خصلت و پرمعنیترین آرمانهای او در هنرهایش تحقق و تجسم یافتهاند آن هم با شیوایی و استحکامی که در کمتر سند دیگری می توان یافت.

پایه

عصر آهن دوم

حدود قرن نهم پیش از میلاد

ایران، حسنلو

گلدان با نقشهای همپوشان و سه نوار از درختان نخل

حدود نیمه تا اواخر هزاره سوم پیش از میلاد

منطقه خلیج فارس یا جنوب ایران

ریتون با سرِ پیشآمدهی یک گربهوحشی

دورهی اشکانی

حدود قرن اول پیش از میلاد

ایران

گاو زانوزده در حال نگهداشتن ظرفی لولهدار

دورهی پیش ایلامی

حدود ۳۱۰۰–۲۹۰۰ پیش از میلاد

جنوبغربی ایران

Arthur Pope maintained that “Iranian art has been the everlasting gift of the Iranian nation to the global community. Iranian artists have regarded art as a manifestation of divine beauty and majesty.” he maintained that “Iranian art seeks celestial forces.”

Iranian art is a historically significant phenomenon of the highest order. It appears that the primary and most prominent preoccupation of the Iranian ethnic groups has been the pursuit of art. The most comprehensive legacy left from the lives of these peoples, as well as their most valuable contribution to global civilization, is precisely their art and the history of their art sheds light on many aspects of human cultural history. In that earliest human civilization, which emerged over six thousand years ago on the Iranian plateau, art was a fundamental element that maintained a vital role throughout subsequent periods, preserving its distinctive and prominent characteristics over the entire span. This art, which had reached a high level even in its earliest stages, succeeded in producing a long series of masterpieces across numerous fields and in diverse forms-forms that inherently and organically share intrinsic and harmonious connections. The genius and unique spirit of Iran have found their fullest expression in the so-called decorative arts—those arts whose secret impact lies in the beauty of pattern and design. In these disciplines, Iran achieved a mastery that has seldom been challenged throughout the unparalleled history of this land’s culture. This innate talent and aptitude for adornment and decoration shine throughout all Iranian artistic creations. The people of Iran seem to perceive in terms of decorative concepts, as the same clarity and precision of pattern and rhythm are also evident in their poetry and music. Indeed, the particular significance of Iranian art lies in the fact that it serves as the most authoritative representative of the view that the primary purpose of art is not representation, but rather ornamentation and embellishment. This principle is observed in many works of art throughout Asia. And it is also evident in certain periods of European art-especially during eras marked by close interaction between Europe and the Orient. On the other hand, Asian art has also, at times, accepted representation as its own goal. However, in general, these two perspectives conflict with each other and are based on different theories regarding the nature of reality and the relationship of humans to it. Nevertheless, these two types of art are not incompatible with each other, as in the finest examples of any art both aspects are observed; although their proportion varies according to the spirit of the culture in question. In Iran, the principle of ornamentation has very rarely diminished in its authority.

In Iranian art, this intense passion for ornamentation has been realized and manifested -more or less throughout all periods- with consummate technical skill and abundant creative ingenuity. It is difficult to find an equivalent even for the oldest decorated pottery, despite all the technical advancements developed in the centuries that followed. These pottery pieces, with their fearfully delicate thinness and pleasing smoothness and finesse, are covered in motifs masterfully designed for each individual vessel and their striking originality and vivid character dazzle the eye. The oldest ceramic works in the world are still, in a sense, considered the finest. It is true that the art of pottery declined from the Achaemenid period to the end of the Sasanian era; however, it experienced a revival in the early centuries of Islam. In terms of elegance, aesthetic form, color variety, lively character, visual appeal, and the harmony of ornamentation, Iranian vessels of that era elevated the art of glazed pottery to unprecedented levels of perfection. This same mastery in creating diverse, harmonious, and eloquent ornamentations adorned with coordinated colors, combined with delicate craftsmanship and technical skill, enabled similar achievements across various other types of artifacts. Thus, all the capabilities of carpet weaving were employed, resulting in qualities in textiles that stood proudly above all standards. Moreover, these talents had a significant impact on all other arts and even on industry. There was nothing that humans made or used that, due to their innate sense of taste, did not take on a beautiful form: from gardens and manuscripts to weapons, clothing, and household furnishings. The same care and effort were devoted to creating these as were typically invested in what are considered the so-called major arts. In summary, wherever there were materials capable of taking on a beautiful form, displaying colors that could be combined, or serving as a medium for ornamentation, the Iranians transformed those spaces into fields for expressing their imagination and creativity.

Ornamentation and Representation

However, ornamentation was not an immediate or ultimate act. The instinct for representation, though not equally fundamental, was nevertheless present on the scene-not only persisting, but engaging with the authority of ornamental art. Yet this ornamental art had earned its superiority through competition, having prevailed after traversing other modes of artistic expression. Even sculpture, though limited in Iran-especially after the advent of Islam due to religious prohibitions-possesses a long and distinguished history in this land. Nevertheless, representational arts generally respected the spirit of Iranian ornamental practice; so much so that pure design and form permeated these more tangible and inclusive arts, guiding their expression. As early as the third millennium BCE, sculptors were creating animal figures which, although ornamental in form, were accompanied by a precise understanding of the subject’s beauty and a genuine sense of sculptural expression. At the beginning of the second millennium BCE, cast bronze animal figures from the western and northwestern regions of Iran exhibit a convincing naturalistic representation through well-proportioned and engaging designs. Around the same period, sculptors undertook a more challenging experiment in simulation and, with the same keen insight into the essence of animals that had enabled them to successfully create animal figures, they crafted bronze human heads that exhibit prominent character and compelling emotional strength. Achaemenid sculpture demonstrates the highest achievement of Iranian genius in the sublime fusion of pure form and representation. In the depiction of living beings that do not sacrifice elements of their natural qualities for the sake of generic wholeness, the principles of abstract design have become so immortalized that they seem to be the very laws of wisdom and intelligence, emerging from the essence of nature itself. During the Parthian period, despite contact with Greece, the Iranian interest in creating large-scale sculptures nearly disappeared—perhaps due to a sense of inferiority that Iranian sculptors may have felt when compared to the technical mastery and realistic perfection of Greek artisans. However, during the Sasanian era, the ancient national traditions in religion, politics, and art were revived, and sculpture once again found its place. Undoubtedly, Iranian sculptors worked from Roman models-or perhaps even enlisted Roman craftsmen-but the epic scenes they carved from the heart of the mountains vividly depict the most exalted moments in the lives of kings from a dynasty that claimed divine authority and at the same time, these works preserve and renew the age-old devotion to artistic creation. Once again, the organic balance of harmonious relationships and the rhythmic movement of lines and surfaces makes the sustained presence of representational art possible. Although a strikingly vivid realism can be seen on a few truly precious silver plates or certain bronze pieces, these works also retain their ornamental quality, and their impact-enhanced by deliberate selection and well-placed emphasis-reveals a powerful emotional character. During the Islamic period, sculpture, although restricted due to religious prohibitions, did not disappear entirely; the lions seated opposite each other at the base of the ChehelSotoun Palace evoke memories dating back at least to the Sasanian era.

Painting

Painting, as the most precise and comprehensive of the arts-whose raw material encompasses the entire visible world-is particularly susceptible to the temptation of abandoning formal discipline in favor of pure representation; yet, Iranian painting, despite having the entire world open before it and being invited to conquer new territories through technical skill and later artistic achievements, remained faithful to its original inspiration and gave rise to a distinctive form of ornamental and pictorial art. The great works of painting throughout all times and places have paid significant attention to form, and painting-whether in the Far East or in Europe—has been more successful than Iranian painting in inventing diverse compositional structures; but, Iranian painting, like other Iranian arts, has remained more deeply committed to its own abstract ideals. Ornament retained its superiority over representation; the meaning and beauty of purely ornamental elements were embraced with greater sensitivity, and these aspects attained a higher degree of refinement. These elements were not considered secondary; rather, they were integral to the very nature of representation and embodiment, exercising such authority that evading them was impossible. Although painting thus aligns with the view that has prevailed since the birth of art on the Iranian plateau, the concept of form and shape had gained greater breadth and depth. In fact, the beauty of the design was transformed by an imagination that soared beyond the realm of the tangible, elevating it to a higher level. Clarity, precision, and the jewel-like brilliance of the details were accompanied by a kind of fresh poetic insight that seemed to herald a message from another world. Distinct reality blends with a vivid and intricate imagination; mystical insights, which to these poetic people appear genuine and immediate, take on a tangible form both in language and in the art of illumination. The manifestation of divine glory and celestial splendor, which frequently occurs, is always accompanied by clarity; the forms and compositions employed typically correspond to the essence of the work, thereby greatly enhancing its emotional intensity. Here, we witness the movement and passion of love, the narrative of sublime sensitivity, and a state of trance.

Architecture

In architecture, the most tangible of visual arts and perhaps the most demanding test of authenticity and aesthetic capacity, Iran has found ample opportunity and space to embody its ideals and its achievements in this field, which are considerable, are evenly divided across several distinct periods. Iranians invented and perfected distinctive artistic forms and styles that enabled them to develop a type of architecture notable for its grandeur, simplicity, and expressive volume; this volume was adorned by the Iranians with a rich and radiant surface. In the early periods, wooden elements were extensively used in columned structures, but later reflections of this style can be seen in the stone columns of Persepolis, meanwhile, dome and arch architecture is nearly as ancient, and it is in this architectural form that the full potential of brick is realized. These two styles developed alongside each other; one stimulates and satisfies the desire for height and slenderness, while the other, in turn, quenches the thirst for venerating the heavy three-dimensional form as an effective expression of power. In the early Islamic centuries, these two styles merged harmoniously, creating a triumphant masterpiece that embodies a coherent yet clear and beautiful logic-strong yet light, powerful yet humane; exemplified by the northern dome chamber of the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan. However, this is just one example among more than a dozen existing masterpieces, albeit the most beautiful of them; and these masterpieces, being the sole survivors of their kind, must represent a much larger number of now-lost counterparts. These structures demonstrate the profound depth of the Iranian sense of form, which could not be fulfilled or fully realized except in monumental buildings. In these structures, instead of showcasing the exercise of spatial forces, the harmonious arrangement is beautifully composed to express emotions.

The Expansion of Iranian Art

The rationality and practical utility of the various ideas and crafts that Iran invented or developed, the inherent beauty of its arts, and the clear, comprehensible forms employed in their expression all made their widespread diffusion inevitable, moreover, Iran’s position at the heart of Asian culture further facilitated this expansion. Indeed, Iran has, at various times, been in contact with all the great civilizations of the world, transmitting its ideas to them; while simultaneously receiving influences from each-freely, yet with a critical perspective. Iran’s role in the history of architecture is increasingly being recognized, as the Roman style—both in terms of structure and ornamentation-was influenced by Iran, and compelling evidence suggests that Gothic architecture may also owe certain fundamental structural forms to it. It seems highly plausible that the Gothic tendency in its visual quality and vertical form was inspired by the Orient; among the various influences transmitted to Europe through merchants, travelers, and the Crusades, Iranian motifs played a significant role. There is little room for debate about the importance of Iranian art to European art; however, precise evaluation of this influence will occupy scholars for years to come. Ancient Greek and Roman art (classical art), toward the end of its era, found refuge in Sasanian Iran, where its treasure trove of ornamentation was reshaped and revitalized before being re-exported to Europe. Through various trade routes between Russia and Scandinavia and the Mediterranean Sea, Iranian ornamental arts have influenced Europe; and whenever Islamic art as a whole has interacted with or inspired Europe, the Iranian spirit has been a pervasive presence there. Meanwhile, the less developed tribes beyond Iran’s northern and eastern borders-groups that were mostly nomadic but familiar with some Iranian arts and, through their share in the legacy of general Iranian traditions, exhibited many qualities of the Iranian spirit-transmitted and spread Iranian culture beyond Iran’s borders. Because these peoples-the Scythians, the Sarmatians, and their cultures-were fundamentally within Iran’s sphere of influence, and perhaps, as some scholars believe, were ethnically and linguistically related to the peoples of the Iranian plateau. These peoples transmitted many characteristics of their artistic style, illustrative techniques, and even folklore to the Goths, Visigoths, and some other Berber tribes; these elements, after being introduced to Europe, became one of the main factors shaping pre-Charlemagne art and left a lasting imprint of form and meaning in early medieval Europe. For tens of centuries, Iran has been a significant power in Asia. Several pieces of evidence indicate that motivations originating from the Iranian Plateau played a decisive role in the emergence of the concept of art in Mesopotamia. The connections with India date back to before the Aryan invasion, confirming a form of unity that goes beyond differences in deeper temperaments. The traces of Iranian influence in India, which were evident during the Achaemenid and Sasanian periods, were renewed around the year 1000 CE and again with the Afghan invasions, as it should be remembered that the Afghans were Iranian and carried elements of Iranian culture with them. During the reign of the Ghurkani rulers (commonly known as the Mughals of India), Iranian influence remained predominant throughout much of the Indian subcontinent, and during this period, the court and nobility drew significant cultural inspiration from Iran. Trade between Iran and the Far East was continuous, complex, and long-lasting. In ornamental arts, styles and trends, as well as various practical crafts, were exchanged during this interaction. Moreover, Iranian culture transformed the early form of Buddhism, as this religion passed through Iranian territories on its way to China and absorbed various religious ideas-particularly from the source of the Mithraic faith-which eventually evolved into the sect known as Amida.

The Comprehensive Significance of Iranian Art History

Since Iran thus played a profound role in the development of other cultures in both the East and the West, art historians of other nations must seek illumination from the history of Iranian art; meanwhile, several other issues also become clarified in this context. Iranian art, due to its longevity, endurance, and superior quality, holds a significant position as a distinct phase within the overall history of culture. Since the cultivation of highly refined arts in the Iranian Plateau coincides with the emergence of the first advanced civilization, these arts help elucidate the extent to which human aesthetic motivation is primordial, ancient, and fundamental, as well as the nature, function, and value of aesthetics in human survival. The study of artistic production with such durability and continuity reveals the major underlying motivations behind it and also clarifies the nature of artistic individuality for us. In this region, religion has overseen the birth of art and, in a way, sustained its life until its period of maturity. For this reason, religion reveals the meaningful relationship between these two fundamental and central human concerns, a relationship that remains not yet fully understood. The relationship between art and poetry is similarly clarified in this way. Because in Iran these two disciplines have been intertwined for long periods, they resemble the relationship between visual arts and poetry in China in this regard. Because Iranians have been a poetry-nurturing nation for many centuries, they have expected their artists not only to depict the narratives conveyed in Persian literature but also to embody the particular modes of poetic thought and feeling. The incorporation of poetry into other dimensions of aesthetics illuminates new and intriguing aspects of poetic motivation and demonstrates its dominance over various creative endeavors. Iranian art similarly maintains a relationship with mathematics; Iranians have engaged in mathematical thinking for centuries, and certain principles of Iranian design undoubtedly reflect specific forms of mathematical thought. The progression of arts and crafts in Iran also demonstrates the important role geography plays in shaping the character and activities of peoples, although this subject has been widely debated and remains somewhat obscure. The changes that, while preserving the unity of character, have occurred throughout numerous social transformations can also shed light on the relationship between aesthetic culture and its political and economic contexts. Ultimately, Iranian art stands as evidence, a legacy, and an interpretation left by a nation that has played a significant role in world history since the earliest times. Iran’s role has been decisive in Asia and significant in Europe. The historical significance of this country’s existence has yet to be fully elucidated; however, its deepest qualities and most meaningful ideals have been realized and embodied in its arts-with a clarity and strength seldom found in any other record.